How does long-acting, injected naltrexone buffer against opioid use?

Extended-release injectable formulations of naltrexone that block the effects of opioids (best known and marketed under the brand Vivitrol) are effective treatments for opioid use disorder. A number of existing theories of behavior change have been put forward to explain how these formulations may help reduce opioid use, but these theories have not been tested empirically. To address this, the authors of this paper used data from a large clinical trial of extended release naltrexone to draw inferences about how these medications help individuals trying to stop opioid use.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

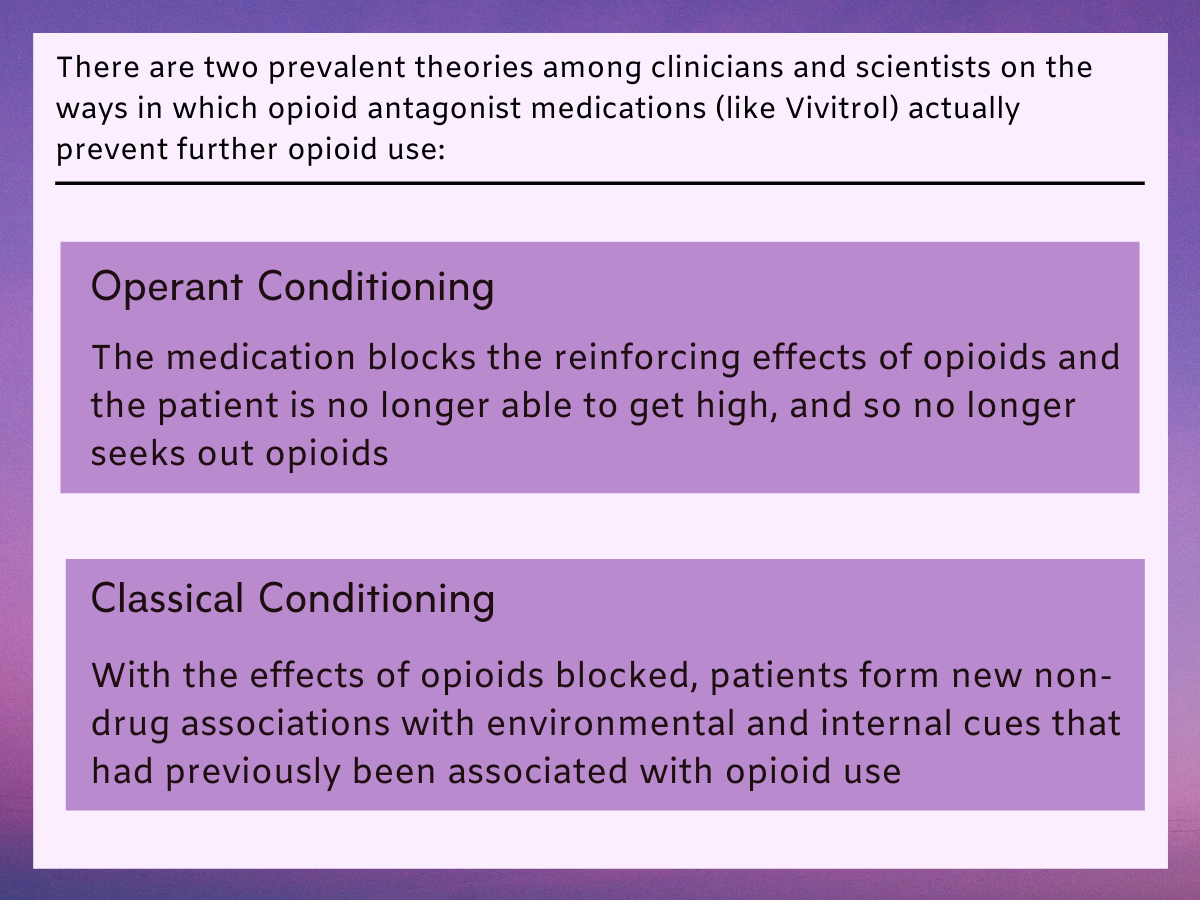

Long-acting, injectable formulations of opioid blocking medications like naltrexone (i.e., opioid antagonists) have been shown to reduce opioid use among individuals seeking recovery from opioid use disorder (see Jarvis and colleagues for review). Clinical scientists have speculated that these medications help people reduce or stop opioid use through operant conditioning (i.e., patients stop seeking opioids because the medication blocks the reinforcing effects of opioids and they can no longer get high), and classical conditioning (i.e., individuals form new non-drug associations with environmental and internal cues that were previously associated with opioid use).

Observations of clinicians working with these patients, however, have suggested that the relationship between long-acting naltrexone formulations and opioid use reduction/cessation is more nuanced. In this paper, Nunes and colleagues speculate that cognitive processes are also likely at play. For instance, if patients take opioids and experience the blocking effects of the medication, they may not try opioids again unless they have stopped the medication and know it has worn off. Other explanations for the medication’s utility are that patients may be refraining from taking opioids because they believe the effects will be blocked (i.e., reduced positive expectancies of opioid use), even if they have not personally tested this assumption. These medications may also work by reducing craving after exposure to experiences and cues previously associated with drug use (i.e., classical conditioning). To begin to test these assumptions, the authors of this paper used data from a clinical trial comparing the effects of injection naltrexone to a placebo injection to explore the effect of this medication on opioid use lapses and treatment dropout.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a secondary analysis of data from a randomized clinical trial with 250 individuals meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition) criteria for opioid dependence (now known diagnostically as opioid use disorder) who received either a long-acting naltrexone injection (Vivitrol), or a placebo injection once monthly for six months to see whether long-acting naltrexone would reduce opioid use and treatment dropout following opioid use lapses. This clinical trial was conducted across 13 inpatient treatment programs in Russia between July 2008 and October 2009. In this study, the authors tested whether those randomized to long-acting naltrexone injection were more likely than those who received placebo to remain in treatment after an opioid positive toxicology screen – suggesting injectable naltrexone worked by reducing the reinforcing effects of opioids. They also tested whether the injectable naltrexone group had a greater proportion of participants than placebo who were abstinent throughout the trial – suggesting it worked also by other mechanisms such as reduced cravings.

In the parent clinical trial, after providing informed consent, patients who had completed opioid detoxification within 30 days and had been abstinent from opioids for at least seven days were randomly assigned to receive either active naltrexone injections (n = 126) or placebo injections (n = 124) administered before discharge from the inpatient unit and then every four weeks over 24 weeks of outpatient follow-up treatment (the Vivitrol injection naltrexone formulation lasts for 28 days). Patients in both groups were also offered biweekly individual counseling for opioid use disorder.

Participants in this study were mostly male (88%) and White (99.2%). In terms of primary type of opioid used, 88.4% endorsed heroin, 11.6% methadone, and 13.3% prescription opioids. The average duration of cumulative opioid dependence was 9.6 years. The primary findings of the parent clinical trial were that individuals receiving naltrexone injections had more weeks of opioid abstinence and were more likely to stay engaged in treatment than those receiving placebo, though it is possible these results were partially influenced by differing retention rates between groups. Specifically, because participants who dropped out of treatment were not followed up with, it is not known whether individuals dropped out because of returning to opioid use, or other reasons such as figuring out they were receiving placebo (e.g., because they did not experience side effects) and losing interest in the study.

For their secondary analysis of this data, the authors conducted a survival analysis (a statistical approach that assesses time to an event such as dropout from treatment), using a regression model exploring the relationship between time to dropout (dependent variable), and the interaction between treatment group (naltrexone injection versus placebo) and urine drug test result for opioids (positive or negative) at each study week. Specifically, they tested whether the medication group were more likely to stay in treatment versus the placebo group when their toxicology screens were positive for opioid use in the prior week. Missing urine drug tests were presumed to be positive. The last visit day for patients who dropped out in the randomized treatment phase, consisting of 168 days (24 weeks), was defined as the day of dropout. The authors chose dropout from treatment as the outcome measure because it is the most common failure mode for injection naltrexone treatment of opioid use disorder. They note that patients typically use few opioids while receiving naltrexone injections, but then drop out of treatment, after which return to opioid use is likely. The risk for dropout at a given week of the study was modeled as a function of the history of positive urine drug test results for opioids during the treatment period, treatment assignment (naltrexone injections versus placebo), and their interaction. The authors also hypothesized that compared to patients receiving placebo injections, patients receiving naltrexone injections would be more likely to have no opioid-positive urine drug test results over the six-month study period.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

The authors found a significant interaction effect, such that among patients receiving placebo, positive urine drug test results in any preceding week increased the risk for dropout in a subsequent week by a factor of six, whereas among patients receiving naltrexone injection, positive urine drug test results in any preceding weeks did not affect risk for dropout in a subsequent week. To increase their confidence in this finding, the authors also re-ran this model using a number of different assumptions about missing data, but found similar results.

Next, taking a qualitative approach to better understand the data, the authors plotted treatment attendance and opioid urine drug test results for each participant across a 24-week clinical trial. Several patterns emerged.

Figure 1.

First, consistent with their regression model, among the patients who eventually dropped out of treatment, more patients in the placebo condition had a pattern by which a week with a positive urine drug test result was followed by dropout the next week: 20 of 124 patients (16%) receiving placebo compared with 4 of 126 patients (3%) receiving injection naltrexone. Meanwhile, a roughly equal number of patients receiving placebo (52 of 124; 42%) and patients receiving injection naltrexone (52 of 126; 41%) had a negative urine drug test result in the week before dropout.

Secondly, in the group receiving injection naltrexone, weeks of opioid use tended to occur in isolation; in other words, a positive week was typically immediately followed by a negative week. In one or more instances in 16 of 124 patients (13%) receiving placebo, a week with a positive urine drug test result was followed immediately by another week with a positive urine drug test result, whereas only 6 of 126 patients (5%) receiving injection naltrexone showed this pattern of consecutive weeks of positive urine drug test results. Finally, in absolute terms, more patients receiving injection naltrexone (31%; 39 of 126) were present and had negative urine drug test results across all 24 weeks compared with those receiving placebo (20%; 25 of 124), though this difference did not quite meet statistical significance (p= 0.051), meaning the probability that this finding was a result of chance was slightly greater than the standard accepted threshold of 5%.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Findings are consistent with the idea that long-acting injection naltrexone helps to reduce or end opioid use through its function of blocking the reinforcing effects of opioids during episodes of use. This supports the theory of operant conditioning whereby behavior is shaped by its consequences; if there are no positive effects from opioid use when one is taking naltrexone, then opioid use will diminish or stop. Indeed, patients receiving injection naltrexone who ended up using opioids during the study experienced the blocking effects of the medication, and were inclined to not try opioids again while receiving this medication. Additionally, the qualitative findings reported suggest that among patients receiving injection naltrexone who did show evidence of opioid use, use was sporadic, with most weeks being opioid negative, with the occasional positive week occurring in isolation and not followed by one or more consecutive positive weeks. These findings also suggest the importance of injection naltrexone blocking the reinforcing or priming effects of opioids when patients test the blocking effects of the medication by using opioids.

In addition, the authors sought to test the idea that injection naltrexone would reduce the proportion of patients who tested the medication with any opioid use. This hypothesis was prompted by a previous study, which showed that a third of patients treated with injection naltrexone showed no evidence of opioid use during an eight-week clinical trial. This absence of opioid use suggests an effect of injection naltrexone on the tendency to use opioids that does not depend on personally testing the medication’s effects. In the study summarized here, the proportion of patients who attended all 24 weeks and showed no evidence of opioid use was numerically greater in patients receiving injection naltrexone (31%) than in those receiving placebo (20%), but the difference just missed statistical significance (p= 0.051). More research is needed with larger sample sizes to properly test this hypothesis, and explore possible subjective effects of active naltrexone that may be influencing these results.

The rate of placebo response in this study is notable, with 31% of patients receiving placebo achieving at least 90% abstinence, and 20% receiving placebo present and abstinent across all 24 weekly visits. The authors note that this placebo response could be related to the framework of the clinical trial. Patients in both treatment groups received counseling, and to be eligible for the study they needed a supportive family member who could supervise adherence to clinic visits. It is possible that the belief that effects of opioid use will be blocked with the long-lasting injection, reduced craving and motivation to seek opioids for some patients. And finally, patients’ fear of repercussions for relapse may also have been in play, given that the study was conducted in a country where opioid addiction is particularly stigmatized.

More work is needed to understand the ways in which injectable naltrexone is similar and different to other opioid medications such as buprenorphine (best known by the brand name Subutex) that also have an opioid blocking effect (though not as strong as naltrexone), but in a very different way (i.e., naltrexone is an antagonist and does not produce any opioid effect, whereas buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist that produces a direct opioid effect). A more complete understanding of the similar and differing mechanisms and effects of these medications for different patients will help providers make better treatment decisions better tailored to individuals’ treatment needs. Additionally, more research is needed to help understand how naltrexone might reduce craving. The authors suggest naltrexone could be blocking kappa opioid receptors in addition to mu opioid receptors, and this may be leading to reduced dysphoria and increased wellbeing, but this hypothesis remains untested.

- LIMITATIONS

-

As noted by the study authors:

- This study, and many like it, used dropout from treatment as a proxy for return to opioid use. Though it is likely this was the reason most participants dropped out of treatment, it is also possible people dropped out for other reasons such as adverse medication side-effects or life circumstances.

- This secondary data analysis inferred potential clinical mechanisms of injection naltrexone using data from a clinical trial focused on basic clinical outcomes. As such, the data is not ideally suited to addressing the questions posed by the authors in this study.

- The present findings may have limited generalizability to common clinical settings given participants were required to have 7 days of abstinence from opioids to participate in the study.

Additionally:

- This study did not assess the quantity and frequency of opioid use among participants who used opioids during the study period, and the only indicator of opioid use was a positive urine drug test. Though objective measures such as urine drug tests are a strength, these results provide little qualitative information. Even though abstinence was the desired outcome in this study, reductions in quantity and frequency of opioid use could have been meaningful indicators of treatment effect.

- Participants in the placebo group who had opioid use lapses would have experienced the subjective effects of the drugs, and would have become aware that they were receiving placebo medication. This could have been the basis under which some individuals dropped out of treatment.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: The findings summarized here provide evidence that injection naltrexone in combination with counseling supports individuals seeking recovery from opioid use disorder by reducing opioid use, and in the event of opioid use lapses, buffering against return to regular opioid use. Findings also suggest that injection naltrexone protects individuals against opioid use by blocking the rewarding properties of opioids, thus reducing the likelihood of opioid use. Injection naltrexone formulations like Vivitrol are non-habit forming, relatively safe, and have low side effect profiles. Given their potential to buffer individuals against opioid use and in doing so support opioid use disorder recovery, they bear consideration for individuals who can maintain an initial period of abstinence and seek to stop opioid use, especially for those declining agonist medications like buprenorphine (better known by the brand name Subutex) or methadone that can’t be combined with naltrexone.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: The findings summarized here provide evidence that injection naltrexone in combination with counseling supports individuals seeking recovery from opioid use disorder by reducing opioid use, and in the event of opioid use lapses, buffering against return to regular opioid use. Findings also suggest that injection naltrexone protects individuals against opioid use by blocking the rewarding properties of opioids, thus reducing the likelihood of opioid use. Injection naltrexone formulations like Vivitrol are non-habit forming, relatively safe, and have low side effect profiles. Given their potential to buffer individuals against opioid use and in doing so support opioid use disorder recovery, they should be considered in opioid use disorder treatment plans, especially for individuals declining agonist medications like buprenorphine (better known by the brand name Subutex) or methadone.

- For scientists: The findings summarized here provide evidence that injection naltrexone in combination with counseling supports individuals seeking recovery from opioid use disorder by reducing opioid use, and in the event of opioid use lapses, buffering against return to regular opioid use. Findings also suggest that injection naltrexone protects individuals against opioid use by blocking the rewarding properties of opioids, thus reducing the likelihood of opioid use. More work is needed, however, to fully articulate injectable naltrexone’s full array of mechanisms of behavior change. Additionally, future studies in this area will benefit from including a follow-up component in their design to assess the longitudinal effects of injection naltrexone, while controlling for potential confounding effects of differential retention rates between treatment groups.

- For policy makers: The findings summarized here provide evidence that injection naltrexone (best known by the brand name Vivitrol) in combination with counseling supports individuals seeking recovery from opioid use disorder by reducing opioid use, and in the event of opioid use lapses, buffering against return to regular opioid use. Findings also suggest that injection naltrexone protects individuals against opioid use by blocking the rewarding properties of opioids, thus reducing the likelihood of opioid use. Increasing accessibility to injection naltrexone formulations, adding to policies that also increase access to buprenorphine, is likely to have strong and positive public health impact.

CITATIONS

Nunes, E. V., Bisaga, A., Krupitsky, E., Nangia, N., Silverman, B. L., Akerman, S. C., & Sullivan, M. A. (2020). Opioid use and dropout from extended-release naltrexone in a controlled trial: Implications for mechanism. Addiction, 115(2), 239-246. doi:10.1111/add.14735