Buprenorphine vs. extended-release injectable naltrexone: A head-to-head comparison

Questions remain about the comparative effectiveness of buprenorphine vs extended-release injectable naltrexone in preventing relapse. This study evaluated the effects of buprenorphine compared to long-acting naltrexone on opioid relapse risk.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Long-term recovery for individuals with opioid use disorder can be particularly difficult. Many individuals return to opioid misuse within the first week of abstinence, with relapse to daily opioid use occurring at rates as high as 91% after medically managed withdrawal. Medication treatments for opioid use disorder (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine, extended-release injectable naltrexone) help promote successful recovery outcomes, including their ability to reduce the risk of relapse.

Agonist medications like buprenorphine (also known by the brand names, Suboxone and Subutex) are the most commonly prescribed treatments for opioid use disorder. Extended-release injectable naltrexone (also known by the brand name, Vivitrol) is an antagonist that is somewhat less commonly used because it requires a period of complete opioid abstinence prior to starting the medication and this can be difficult for some patients. Nonetheless, agonist and antagonist medications are generally shown to be equally safe and effective at reducing substance misuse and opioid craving during treatment, and to have similar retention rates. However, findings concerning relapse are mixed. While one U.S. study (commonly referred to as the X:BOT study) found buprenorphine to be better than extended-release injectable naltrexone at protecting against relapse (i.e. time to first relapse over 24 weeks), a second study conducted in Norway found that both medications produced comparable relapse rates (i.e. total number of illicit opioid negative urine drug screens). However, these studies also used different approaches to analyze their data, which muddies interpretation and conclusions.

Given the relatively high rates of relapse observed for opioid use disorder, and the increased risk of overdose upon a return to opioid misuse and discontinuation of medication treatment, additional research is needed to determine which medications are best for protecting patients from a return to opioid misuse. Doing so can help identify which medication treatments are best for those at increased risk of relapse, which can inform individualized treatment plans that are grounded in science.

To better clarify the effectiveness of these medications for preventing relapse, this current study used data from the Norwegian study (mentioned above) to evaluate the effect of buprenorphine versus extended-release injectable naltrexone on opioid relapse risk among individuals with opioid use disorder, using outcome variables consistent with the U.S. based X:BOT study data to facilitate cross-study comparisons.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a secondary data analysis of a 12-week, multicenter, open label randomized clinical trial examining the effectiveness of buprenorphine and extended-release injectable naltrexone for opioid use disorder treatment. The study was conducted in Norway and included participant follow-up for 48-weeks.

Participants were recruited between 2012 and 2015 from outpatient and detoxification clinics in Norway. During this time, extended-release injectable naltrexone was not yet generally available for the treatment of opioid use disorder in Norway. Thus, participants may have been motivated to join this study in hopes of receiving this new medication, as opposed to buprenorphine, and most of this study sample is assumed to have a preference for or motivation to receive extended-release naltrexone treatment. Upon qualifying for the study, patients completed medically supervised withdrawal (i.e. detoxification) if necessary, and were randomized to one of two treatment conditions thereafter. All participants included in the current analysis were abstinence-motivated patients with opioid use disorder (i.e. opioid dependence, based on the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th edition, or DSM-IV), who received at least one dose of medication treatment, and completed at least one study assessment after randomization. Participants were randomized (1:1 ratio) to receive (1) daily sublingual buprenorphine (dose range: 8-24 mg; n=72) or (2) extended-release injectable naltrexone (380 mg intramuscular injection; n=71) once every four weeks. After completing the 12-week trial, patients had the opportunity to opt into the follow-up portion of the study (36 additional weeks, i.e. week 48 of treatment). Participants completed study assessments every 4 weeks following study enrollment.

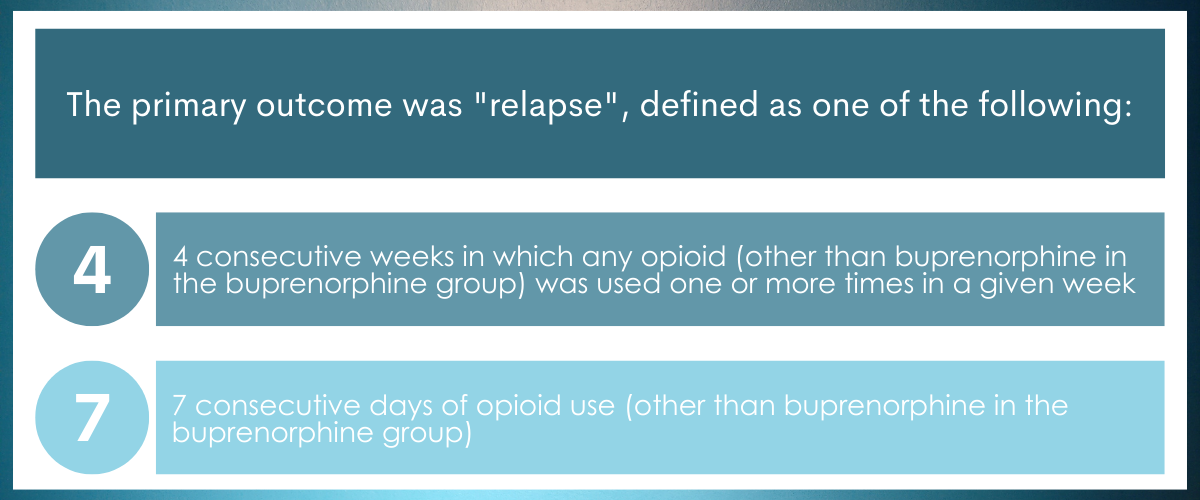

The primary outcome was “relapse”, measured via self-reported opioid use, and defined in a way that matched the U.S. study conducted by Lee and colleagues to facilitate cross-study comparison (see description in the figure below). The researchers examined (1) time to first relapse and (2) risk of any relapse (i.e. 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc.). Relapse risk was assessed in two treatment windows: (1) during the 12-week trial (treatment weeks 0-12) and (2) during the 36-week follow up period (i.e. treatment weeks 12-48).

After the initial 12-week trial, participants had the opportunity to switch to extended-release injectable naltrexone or buprenorphine. Because few of the patients in the trial decided to stay on or switch to buprenorphine, the authors compared patients who remained on extended-release injectable naltrexone to patients who switched from buprenorphine to extended-release injectable naltrexone for the assessment of relapse during 36-week extended follow up.

At week 12, 79% of participants in the extended-release injectable naltrexone group and 85% of the buprenorphine group were still actively participating in the study. Of those not lost to follow-up at week-12, 72% switched from buprenorphine to extended-release injectable naltrexone (n=44) and 79% of the naltrexone group remained on naltrexone (n=44) and opted into 36-weeks of additional follow-up. At the end of the follow-up (week 48), about 41% of the original sample (n=29 per group) were retained in the study.

Importantly, the authors also conducted sensitivity analyses to evaluate the influence of relevant variables on relapse-related outcomes (i.e. opioid and other drug/alcohol use, injecting days, mental health, and money spent on drugs in the 30 days prior to study enrollment).

The study sample primarily consisted of men (74%) in their mid-thirties (mean age: 36 years). Participants had used heroin for about 6 to 7 years and experienced an average of 4 overdoses across their lifetime. Approximately 92% had a history of injection drug use. In the 30 days prior to enrollment, illicit opioid use occurred on 14 days in the buprenorphine group and on 8 days in the extended-release injectable naltrexone group.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Across the 12-week trial period, extended-release injectable naltrexone was better at reducing relapse risk.

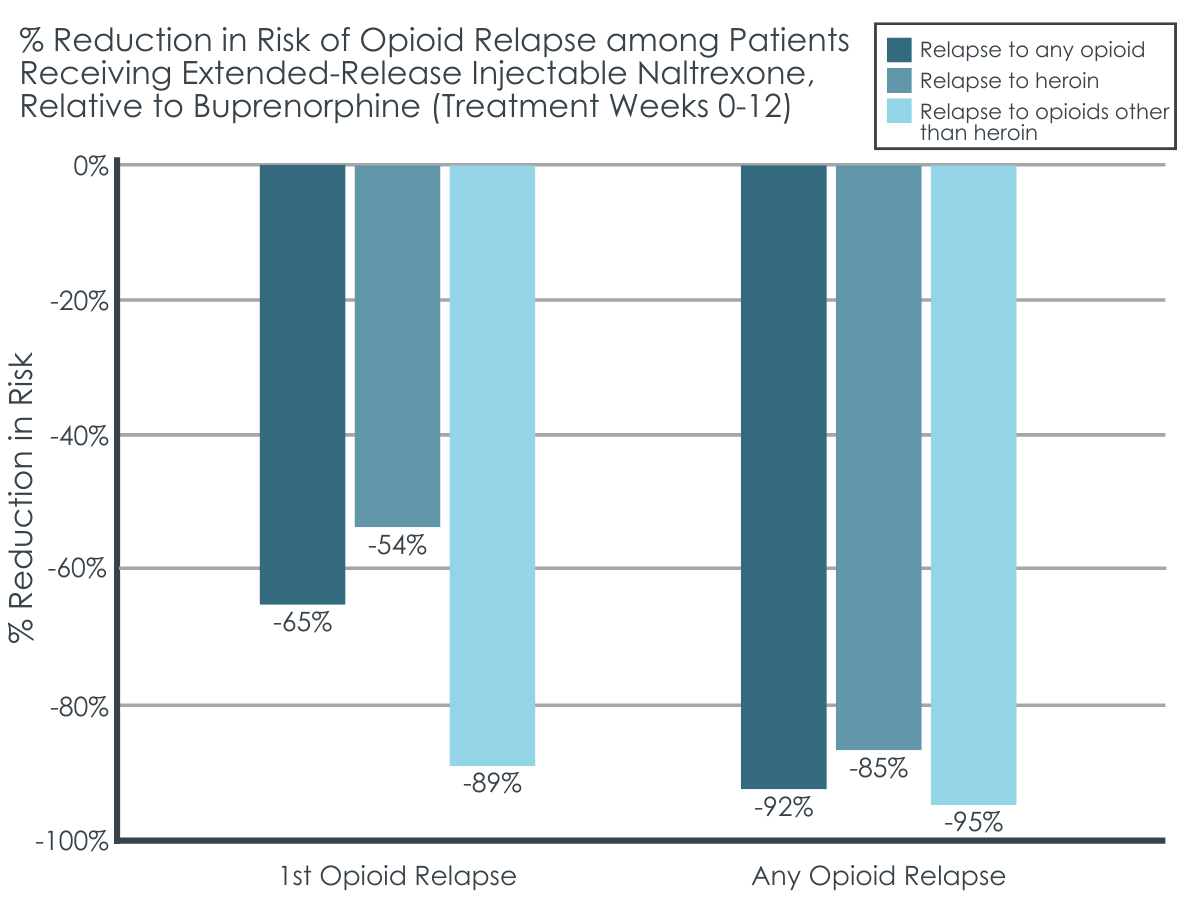

Compared to patients randomized to receive buprenorphine, those randomized to receive extended-release injectable naltrexone had a 54% reduced risk of first relapse to heroin and an 85% reduced risk of any relapse to heroin Concerning relapse to opioids other than heroin, those assigned to extended-release injectable naltrexone were also at lower relapse risk, with an 89% reduced risk of first relapse and a 95% reduced risk for any relapse respectively, when compared to buprenorphine. When the researchers accounted for potential confounding variables (e.g., disorder severity at baseline), these outcomes did not change.

Figure 1. The figure above depicts the percent reduction in opioid relapse risk across the 12-week trial period among the extended-release injectable naltrexone group, relative to the buprenorphine group. The figure shows relapse risk by opioid type (any opioid, heroin, & opioids other than heroin) and by relapse type (risk of the first occurrence of a relapse & risk of any relapse regardless of whether it was the first or not).

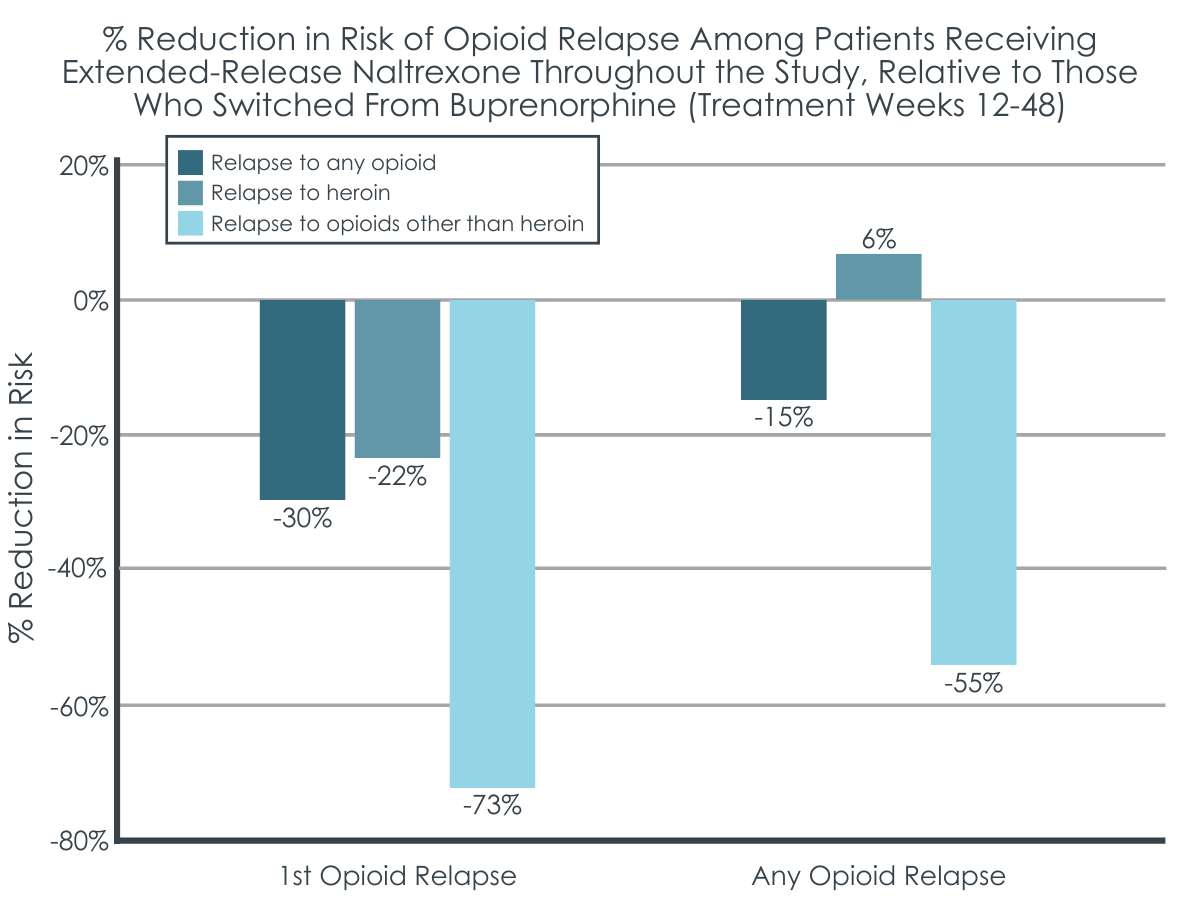

During extended follow-up, patients who started the trial on and remained on extended-release injectable naltrexone had lower risk of opioid relapse.

When the researchers evaluated treatment weeks 12 through 48, patients who initiated extended-release injectable naltrexone at the start of the study and who decided to continue this medication at treatment week 12 had a 55% lower risk of experiencing any relapse to opioids other than heroin, compared to patients who started the trial on buprenorphine and switched to extended-release injectable naltrexone at week 12. This reduced risk only occurred during the first 4 weeks of follow-up (fist 4 weeks of treatment for those who switched to naltrexone). However, when analyses accounted for other potentially influential variables (e.g., disorder severity at baseline), group differences in risk were no longer significant. No significant difference was observed between those patients who remained on extended-release naltrexone across the follow up and those who started on buprenorphine and then elected to switch to extended-release naltrexone, in their risk for first relapse to heroin or other opioid use, or for any relapse to heroin use.

Figure 2. The figure above depicts the percent reduction in opioid relapse risk across the 36-week follow-up period among patients who initiated and continued extended-release injectable naltrexone, relative to those who initiated buprenorphine and switched to extended-release injectable naltrexone at week 12. The figure shows relapse risk by opioid type (any opioid, heroin, non-heroin opioids) and relapse type (risk of the 1st relapse & risk of any relapse regardless of whether it was the 1st or not). Though 1st relapse to non-heroin opioid use approached significance, the only significant outcome was for any relapse to a non-heroin opioid substance, which was driven by relapse rates during the first 4 weeks of treatment in those who switched from buprenorphine to naltrexone. This effect disappeared when substance use severity was controlled for.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Studies like this help us better understand medication treatments for opioid use disorder and their effectiveness for different recovery outcomes. Characterizing the effects of extended-release injectable naltrexone versus buprenorphine on opioid relapse risk can help further our understanding of these medications and guide clinical treatment. This study found that, during the first 12 weeks of treatment, extended-release injectable naltrexone was associated with less risk of opioid relapse (heroin and other opioid use) compared to buprenorphine, and outcomes did not change when controlling for severity of substance use histories. Thus, in this study, the early stages of treatment appeared to favor extended-release injectable naltrexone as a medication for preventing opioid misuse during the first 3 months of treatment.

Interestingly, these findings are in contrast to a prior clinical trial conducted in the U.S. (X:BOT study) despite similar participant inclusion criteria, which found that buprenorphine was equivalent to extended-release injectable naltrexone in terms of preventing relapse during a 24-week period (among patients who successfully initiated the medication treatment to which they were randomly assigned).

The authors of the current study re-evaluated data from the U.S. based X-BOT study to test whether outcomes differed for the first 12-weeks of treatment, but X-BOT study results were still inconsistent with the current study’s outcomes (buprenorphine was still equivalent to naltrexone in the X-BOT study). Unfortunately, the reasons for the discrepant findings between studies conducted in the U.S. and Norway remain unclear.

Perhaps findings have to do with the study methods, patient samples and their preferred treatment, or country-specific opioid use trends (e.g., prevalence of fentanyl vs. heroin use in various countries). It is worth mentioning that the patients in the current study could only obtain access to extended-release injectable naltrexone through participation in this study, and most patients were motivated to participate in the study because they wanted non-opioid based medication treatment to avoid the stigma associated with the use of methadone and buprenorphine medications. All participants were also abstinence-motivated patients who completed at least one study assessment and naltrexone is often perceived as more congruent with an abstinence-based recovery pathway than opioid agonist treatments like buprenorphine. Therefore, results from this study suggest that extended-release injectable naltrexone is better than buprenorphine for reducing relapse risk among those who are highly motivated to achieve abstinence-based recovery and who are receptive to antagonist medications like depot naltrexone. It may be that individuals who are less motivated to abstain or ambivalent to change could be as, or perhaps more, successful with buprenorphine treatment. Motivation and reasons underlying treatment desires are important to consider when starting medication treatment for a given patient and developing personalized treatment plans. Given the convenience of a once-monthly injection, additional research that compares extended-release injectable naltrexone to extended-release injectable buprenorphine, as opposed to daily oral buprenorphine doses, will also offer more direct comparisons that control for route of medication administration and potentially reduce the perceived stigma of daily agonist dosing. Doing so will help clarify the individual benefits of these different medications when the convenience of dosing is equivalent between medications.

It is important to note that extended-release injectable naltrexone can be difficult to initiate because it requires a period of complete abstinence before treatment can start (to prevent inducing opioid withdrawal once naltrexone is started). In a prior study, only about 72% of patients randomly assigned to extended-release naltrexone successfully started it (vs. ~94% assigned to buprenorphine), presumably because of this difficulty of maintaining abstinence from opioids prior to beginning it. Consistently, about 37% of participants assigned to the naltrexone group in the current study failed to initiate this medication so it may not be appropriate for all patients. Furthermore, when patients discontinue extended-release injectable naltrexone they have a reduced tolerance to opioids, and this puts them at greater risk of overdose should they return to opioid use at high enough doses, such as those used prior to treatment. Discontinuation of medication treatment also can occur more frequently with extended-release injectable naltrexone than buprenorphine. Buprenorphine, on the other hand, is a partial opioid agonist and, as an agonist, it allows a patient to maintain a certain degree of opioid tolerance. Thus, a return to opioid use upon discontinuing buprenorphine treatment offers significantly greater protection from fatal overdose.

Because relapse or ongoing opioid misuse is often a common occurrence in the early stages of medication treatment and in the course of recovery, buprenorphine may be a safer option overall, because it is better at preventing overdose when treatment is ceased. On the other hand, if a patient is able to successfully complete opioid detoxification before treatment and is highly motivated for abstinence-based recovery, extended-release injectable naltrexone might be more effective at preventing relapse.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The original study did not take sex or detoxification site into consideration when patients were randomized the treatment groups. In contrast, the US study took site and severity of opioid use into account when randomizing patients to the treatment medication group. Although the authors noted that the addiction severity index was similar between treatment groups in this report, the data were not reported and the inventory may not have been opioid specific. Although not significantly different between groups, the descriptive data suggest somewhat greater severity indicators among participants assigned to receive buprenorphine and this may have influenced outcomes. That said, most of these patients assigned to buprenorphine still chose to change to extended-release naltrexone when given the opportunity to do so.

- Urine drug screens were collected as a part of the study, but were not included as part of this evaluation. Though their prior data showed correspondence between self-reported drug use and urine drug tests, additional research is needed to replicate these findings using bio-verification. Extended-release injectable naltrexone was not yet available in Norway and most patients were therefore assumed to be motivated to receive it through this study. Additionally, the researchers reported these patients were generally abstinence-motivated. This motivation for abstinence and naltrexone may have influenced poorer outcomes observed among the buprenorphine group as those patients may have been disappointed on being assigned to that treatment group.

- Some patients were already receiving agonist medication treatment at the time of enrollment, such that individuals on agonist treatments who were assigned to receive extended-release naltrexone were required to undergo detoxification prior to starting the study-assigned antagonist medication. This transition may have influenced the patient’s treatment trajectory and subsequent relapse-related outcomes.

BOTTOM LINE

Characterizing the effects of extended-release injectable naltrexone versus buprenorphine on different recovery outcomes, including opioid relapse risk, can help further our understanding of these medications to better treat opioid use disorder and help patients maintain recovery. This study found that, controlling for severity of substance use history, extended-release injectable naltrexone was associated with a greater reduction in the risk of opioid relapse during the first 12 weeks of treatment, relative to buprenorphine. More specifically, naltrexone reduced the risk of relapse by 65% (first relapse) to 92% (any relapse). Patients who remained on extended-release injectable naltrexone and those who switched to it from buprenorphine when given the option after the initial 12-week trial had similar outcomes. Study contexts – including the current study’s sample that may have been particularly motivated to receive extended-release injectable naltrexone and had an abstinence recovery goal are important to consider when applying these findings to clinical recommendations. While extended-release injectable naltrexone may be as good or better than buprenorphine for some patients, buprenorphine may be a better option to prevent overdose and for those who are more ambivalent about abstaining from opioid use entirely. Future research should focus on understanding which medications are most effective for which types of people and which outcomes of interest.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Buprenorphine and extended-release injectable naltrexone are both safe and effective medications for the treatment of opioid use disorder. Both medications are proven to be lifesaving first line therapies that can help patients recover from opioid use disorder, reduce craving, prevent overdose during active treatment, and prevent relapse – though the exact medication that does this best remains up for debate. Interested individuals should speak to their healthcare providers to learn more about these medications, discuss their goals, and determine which one might be best for them.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Buprenorphine and extended-release injectable naltrexone are both safe and effective medications that address craving, help prevent overdose and relapse. Although this study suggests naltrexone may be more effective than buprenorphine at relapse prevention during the early stages of treatment, a similar study revealed the opposite. It is not yet clear if one of these medications is better than the other at preventing a return to opioid misuse, but patients’ goals and clinical needs are likely important factors when selecting the ideal medication for a particular individual. Nonetheless, both medications are first line treatments that benefit patients and selection of a particular medication should be considered in the context of a given patient’s circumstances and preferences.

- For scientists: Additional research is needed to replicate and extend these findings, and to identify the factors contributing to discrepant findings between studies conducted across various populations and in various countries. Additional randomized controlled trials comparing all available medications could help characterize the effects of various medication treatments on multiple opioid use disorder recovery outcomes and the patient characteristics that influence medication efficacy. Investigation of longer follow-up periods will also help determine the long-term benefits of various medication treatments. Given less successful induction and retention rates for extended-release injectable naltrexone, it is also important to identify new methods that facilitate induction and retention for this medication. Studies that are specifically designed and powered to test moderators are needed.

- For policy makers: Preliminary evidence regarding the comparative benefits of medications for opioid use disorder treatment (buprenorphine, methadone, extended-release naltrexone) is emerging, but findings are still mixed, and additional high-quality studies are needed to determine the reasons for these discrepancies. Doing so can help guide clinical practice and individualized treatment. Though it remains unclear which medication is best for preventing relapse, we know that all of these medications can help reduce relapse risk and benefit other recovery outcomes (e.g., craving). Additional funding is needed to replicate and expand these findings, and to determine the patient characteristics that influence medication efficacy.

CITATIONS

Opheim, A., Gaulen, Z., Solli, K. K., Latif, Z. E. H., Fadnes, L. T., Benth, J. Š., … & Tanum, L. (2021). Risk of Relapse Among Opioid‐Dependent Patients Treated With Extended‐Release Naltrexone or Buprenorphine‐Naloxone: A Randomized Clinical Trial. The American Journal on Addictions, 30(5), 453-460. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13151