An online alcohol intervention (VetChange) reduces male veteran drinking, but more research needed for women

Compared to men, women tend to engage with online alcohol interventions at higher rates, yet they also tend not to benefit as much. By paying attention to specific groups of individuals with alcohol use disorder and other forms of harmful drinking, researchers can help explain why women might not benefit from online interventions as much as men, informing more gender-sensitive approaches. This study aimed to examine whether the online alcohol intervention, VetChange, was effective in changing participants’ alcohol use and if there were gender differences in participation and outcomes.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

War veterans are often at higher risk for mental health conditions, and they tend to exhibit different treatment engagement and recovery patterns than non-veterans; for example, when returning from war conflicts, they are more likely than other peers to engage in hazardous drinking. One factor in this context is that many veterans are also often dealing with posttraumatic stress symptoms or disorder (PTSD), a comorbid mental health condition that can negatively influence their ability to cope with stressors and manage alcohol use on their own. Additionally, there are differences between men and women in their level of engagement with online alcohol interventions as well as in their alcohol use treatment outcomes; women tend to engage in online interventions at higher rates than men, but they benefit less compared to men.

The reasons for the potential differences in effectiveness of online supports between men and women are not known but could be present because the interventions are not targeting the specific barriers to change for women. There may be additional factors leading to drinking problems for women, for example, that are not addressed in these alcohol use interventions (e.g., other types of traumatic experiences such as military sexual trauma or intimate partner violence).

The VetChange program is a VA-wide online program designed specifically for veterans to reduce their alcohol use and posttraumatic stress symptoms. VetChange was originally studied in a randomized controlled trial and showed reduced drinking and posttraumatic stress symptoms among participants who engaged in the program. This follow-up naturalistic study examined whether the VetChange program is effective in changing participants’ alcohol use and posttraumatic stress symptoms. As well, given the differences between men and women in alcohol use disorder treatment response, this study also sought to examine whether there were differences between men and women in both their level of engagement with the intervention and subsequent outcomes.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a single group, naturalistic study of 222 registered participants (July 2015 – January 2017) in the online VetChange program, an online intervention described as a “self-management” program, followed over 6 months.

Participants were included if they met National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) problematic drinking criteria for inclusion (more than 3/4 drinks per day or 7/14 drinks per week, for men vs. women, respectively). Potential participants were not excluded based on their level of posttraumatic stress symptoms.

VetChange consists of 9 “interactive, psychoeducational and skills-based modules, guided audio and video content and exercises, goal and drinking tracking, and customizable coping and action planning features.” Modules include: (1) Brief assessment and normative feedback; (2) Decisional Balance and goal setting; (3) Skills building for managing risky situations, feelings and moods, stress, and anger.

Figure 1.

The research team assessed participants between the time of registration with VetChange (baseline) and 6 months. During this time, participants were prompted to complete research assessments at 1, 3, and 6 months after registration. All drinking outcomes were measured using the Quick Drink Screen which collects the following outcomes: average number of drinking days/week, average number of drinks consumed per drinking day, number of heavy drinking days, and greatest number of drinks consumed in a single day in the past month. These outcomes were used to generate a binary “low risk” drinking variable (yes/no) which used as a benchmark the NIAAA drinking guidelines by gender. Posttraumatic stress symptoms were measured using the 20-item posttraumatic stress disorders checklist for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5): the checklist ranges from 0-80 and scores of 31-33 indicate the presence of posttraumatic stress disorder. A change of 10-20 points on the checklist would be considered a clinically significant change.

The authors examined whether alcohol use or posttraumatic stress symptoms, when controlling for several participant characteristics (age, race/ethnicity, military and deployment background), differed by gender. The primary analyses focused on the following 3 alcohol outcomes: average drinks per week, number of drinks consumed per drinking day, and the percentage of heavy drinking days in the past month. Secondary analyses included proportional changes in average drinks per week and number of drinks per drinking day at each follow up assessment (relative to their baseline levels) and achievement of “low risk” drinking (less than 3/4 drinks per day or 7/14 drinks per week, for men versus women, respectively) at each follow-up assessment.

This study sample included 222 veterans who had served in Iraq or Afghanistan; the sample was primarily male (76%) and white (78%) and had on average elevated posttraumatic stress symptoms (M = 35.8, SD = 17.7). The study also had a greater proportion of females relative to the overall veteran population (23% versus 9%, respectively).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Males and females showed similar levels of VetChange engagement, but there was also high dropout.

Men and women logged on to the VetChange program at the same frequency, about 5 times on average during the 6 months of the study period. Similar numbers of men and women dropped out of the study across all follow-ups, but these numbers were very high for an intervention of this nature: only half of participants completed the 1-month (52%) and only just over one quarter of participants completed the 6-month research follow-ups (28%).

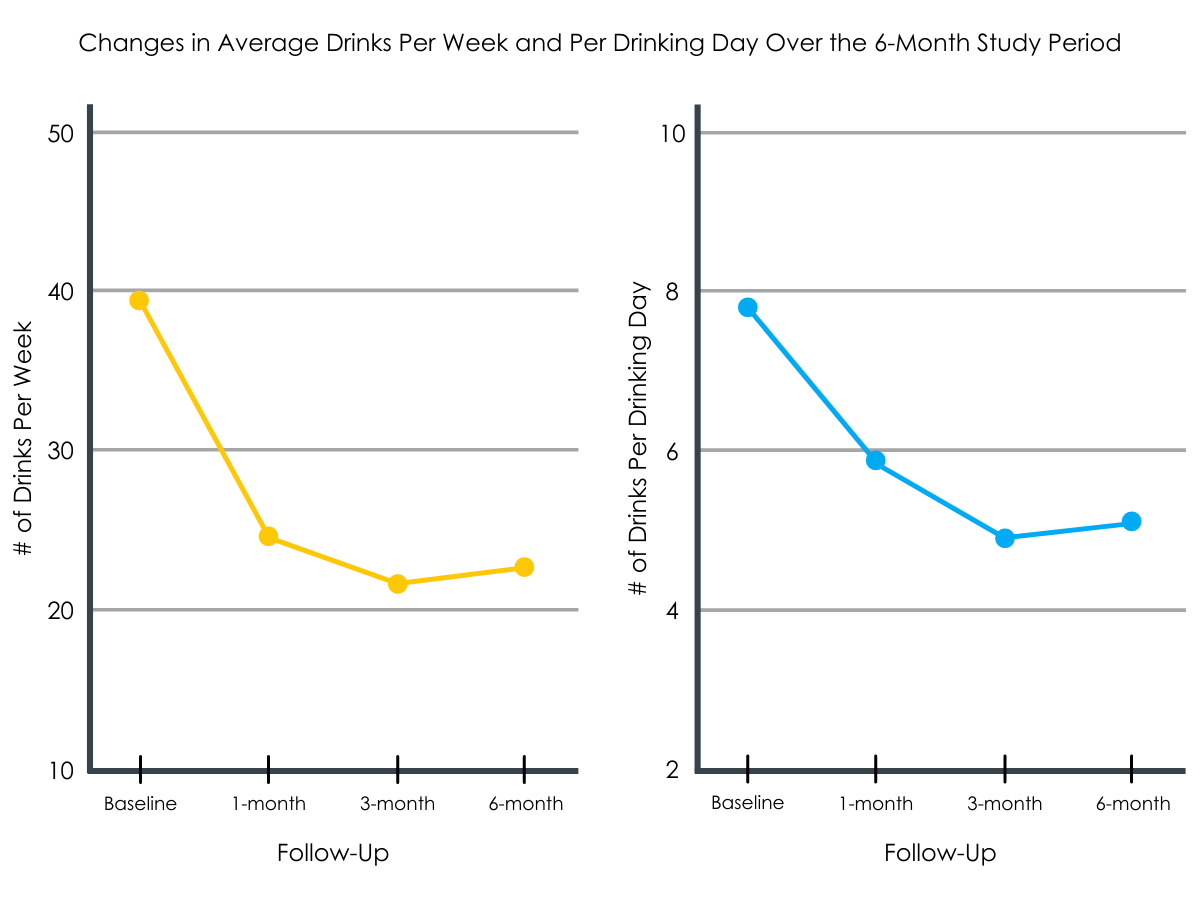

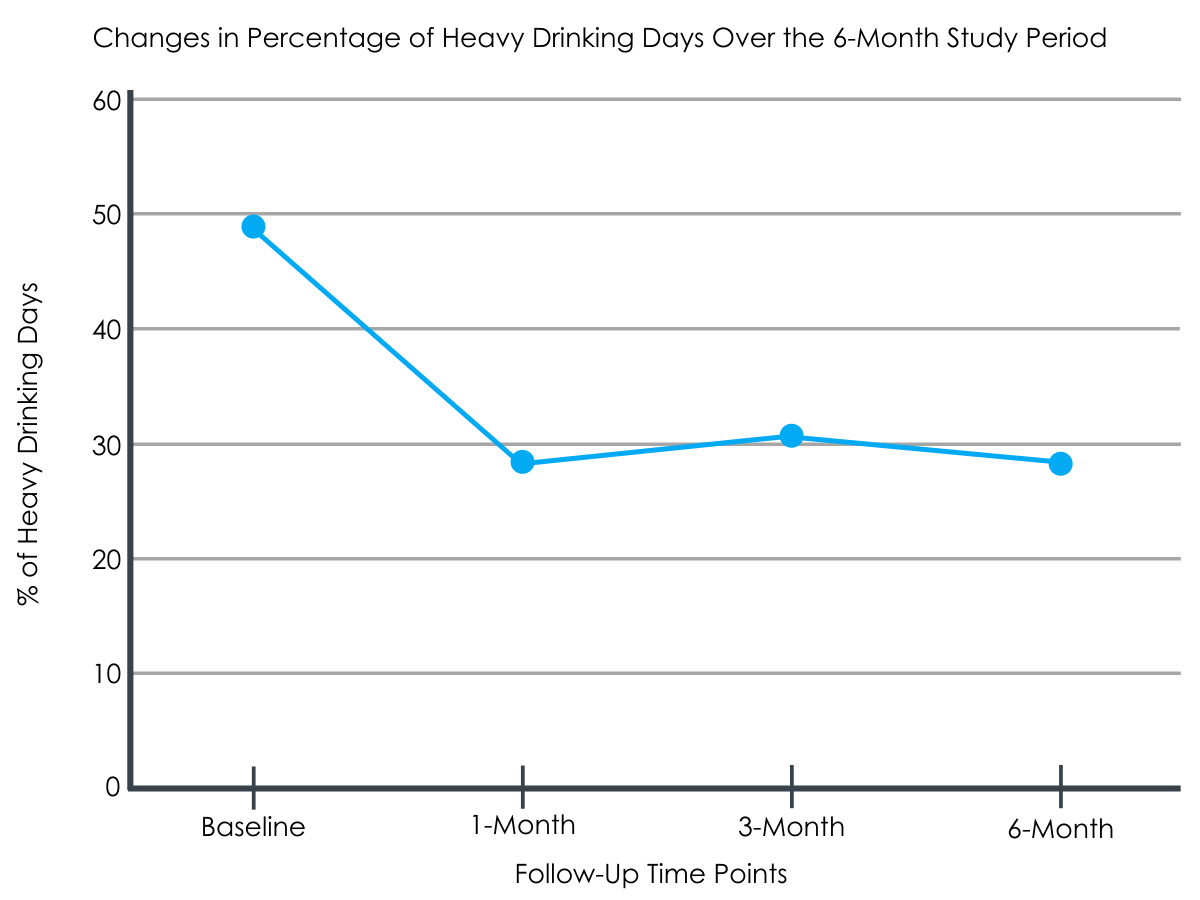

Both veteran men and women reduced their alcohol consumption, but women experienced less reduction on several drinking outcomes.

The greatest rate of drinking change was within the first 30 days of registration with VetChange. Overall, across the 6-month period, average drinks per week, drinks per drinking day, and percentage of heavy drinking days were significantly reduced. Men had a significantly sharper rate of change on average drinks per week and drinks consumed per drinking day than women (but not on percent heavy drinking days or posttraumatic stress symptoms).

Figures 2 and 3.

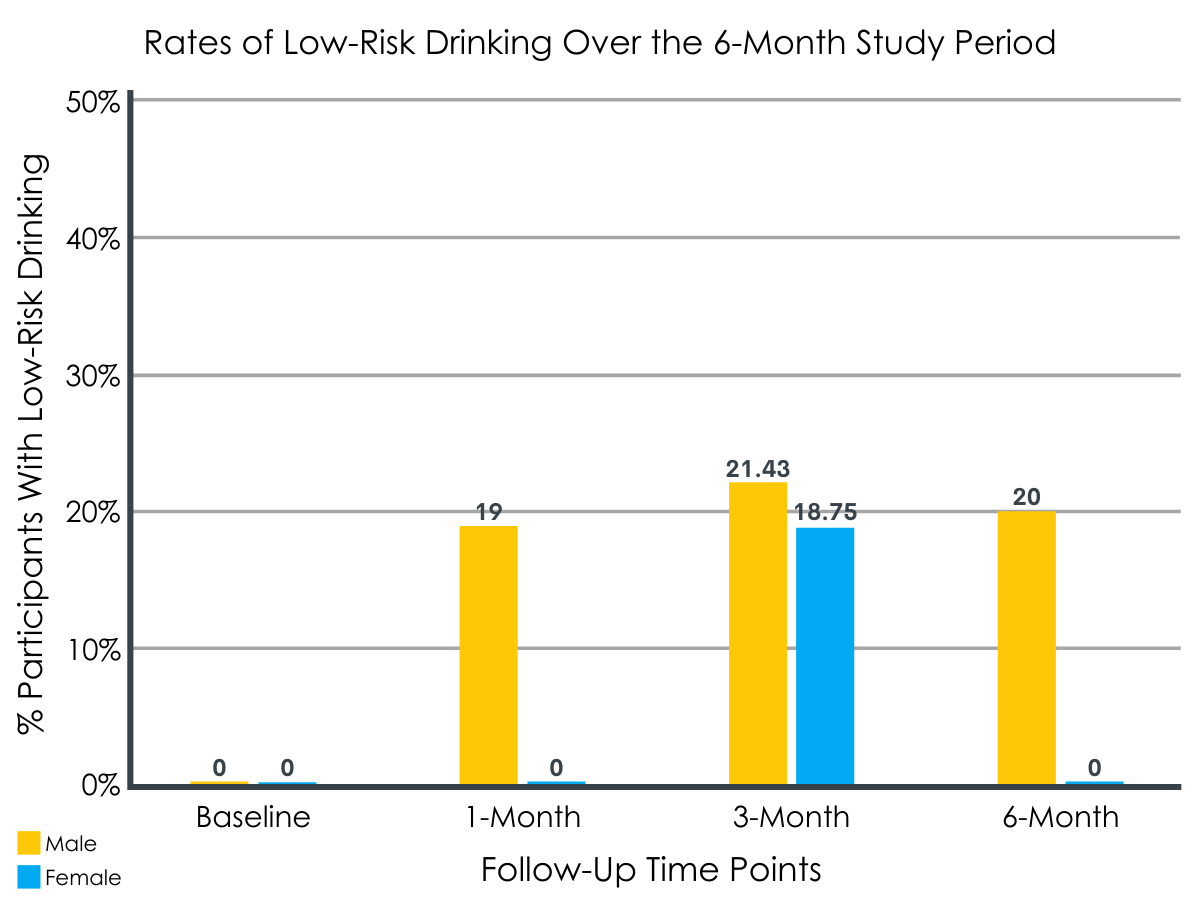

Low-risk drinking differed by gender.

Males appeared to achieve low-risk drinking at higher rates than women participants. In fact, women only achieved low-risk drinking at the 3-month follow-up, a finding that did not persist to the 6-month assessment period, while the overall rate among men did not change after 1 month.

Figure 4.

Both groups experienced reduced posttraumatic stress symptoms.

Although the analytic models did not find evidence of a statistically significant effect (i.e., there was greater than 5% chance the results were due to characteristics of this particular study rather than a true effect in the population), there seemed to be clinically meaningful posttraumatic stress symptom changes. Within the first month, women improved 11 points on the posttraumatic stress symptom scale whereas among men, a clinically meaningful improvement of 10 points occurred from baseline to 3 months.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study examined results from a naturalistic 6-month online intervention trial among veterans who had returned to the US from active duty in 2015-2017. The authors found that the VetChange intervention was overall successful in reducing risky alcohol use and posttraumatic stress symptoms among its participants. However, in line with existing research, there were differences between men and women in their overall outcomes, with men experiencing sharper drinking improvements than women over time. As well, although participants reported reduced posttraumatic stress symptomology, these findings did not reach significance overall with similar reductions in men and women. Finally, there were such high rates of dropout from the study, suggesting that there may have been participant characteristics or intervention characteristics that influenced continued participation in the intervention and subsequent outcomes. Future work to examine why there was such a high level of dropout would be important to conduct as well as whether there are necessary additional supports or changes to the program to help increase participant retention.

Veterans can take longer to access treatment and may accrue more negative consequences during this time, all issues that could hinder their ultimate recovery success. This may make it more difficult for briefer alcohol intervention modalities like VetChange to be effective if they are not targeted towards veterans during early screening. Additionally, although male veterans with comorbid conditions are more likely to receive any sort of brief intervention (the same is not necessarily true for female veterans or for some minority groups), given the level of engagement and ultimate success of these interventions, there is still a gap to reaching those most in need of interventions that address multiple health issues.

Notably, this intervention was not developed with women in mind. Thus, there may be a need to conduct qualitative research about what might work better for women veterans and to involve them in tailoring the online intervention approach to better suit their needs.

Figure 4.

New qualitative research may be most useful if intended to generate hypotheses about mechanisms of behavior change which research has shown can differ between genders. By attending to gender-specific mechanisms, interventions may be more effectively tailored to women based on their AUD recovery-specific needs. Indeed, similar to other studies with veteran populations, the findings from this study suggest that different mediums may work differently for certain subgroups of people, e.g., recovery check-ups (brief phone intervention) versus purely online modalities. As well, there may be a need to more specifically address participant’s views on and engagement with the heavy drinking culture in the military as part of these interventions to enhance participant recovery capital. This drinking culture could be especially salient for those who remain part of the military community upon returning from foreign service and there may be a need for more intensive recovery supports for military service members to connect with others who have had a similar experience (e.g., such as recovery houses).

- LIMITATIONS

-

- There was a large amount of missing data due to participant attrition: only 52% completed the 1-month and 28% completed the 6-month research follow-ups. Thus, those who stayed engaged in the study may have particular resources influencing their recovery than those who left the study, although baseline differences on several basic demographic characteristics (gender, race) and all outcomes were not significantly different between those who remained in the study and those who did not. As well, because this is a naturalistic study of VetChange participation, this level of attrition might reflect difficulties of continued engagement with online self-management interventions.

- The manuscript reported binary gender categories (male, female), but these categories may not reflect the nuances of gender identity that could be present in the sample.

- There was no information about levels of engagement with the platform beyond number of logins, such as the number of modules completed or time spent. Thus, the outcomes based on dosage or other measures of engagement, as well as specific mechanisms of change from this intervention are unclear.

BOTTOM LINE

In this naturalistic study of an online self-management intervention to reduce harmful drinking, called VetChange, participants experienced reductions in risky alcohol use and posttraumatic stress symptoms; however, the degree of non-completion of assessment follow-up in this study is of concern and directly affects what can be gleaned from the findings. Given the high amount of dropout from the study, the intervention may not have been seen as effective for all who initially participated or perhaps it was difficult for participants to have sustained motivation for engaging with the online platform without more explicit support from a clinician or other peers. Although men had improved outcomes compared to women, the dropout of participants suggests there may be more factors involved in continued participation than what the study captured. In addition, although there were changes in posttraumatic stress symptoms among participants, many participants likely still needed additional mental health services to resolve these symptoms.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Evidence suggests that veterans especially are more likely to suffer from mental health issues, such as posttraumatic stress symptoms or disorder and substance use that can exacerbate those feelings and negative outcomes. Identifying and linking those in need of easily accessible resources, such as the VetChange program early on may help to initially stem risky behaviors and negative outcomes. As well, it is important for families with a women veteran in recovery to understand that more tailored resources may be necessary to address her needs, especially to address different barriers to entering treatment and to combat stigma.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: While the online VetChange intervention appeared to be successful in reducing negative symptoms and risky alcohol use, it may be necessary to screen and refer patients early in their care to this resource for maximum effectiveness and to reduce potential barriers and consequences from heavy alcohol use. As well, given that the most robust findings were within the first month of the program, providers might need to follow up with patients outside the 1-month window and assess whether additional recovery supports (for both substance use and mental health symptoms) are necessary. It is important for practitioners to remember that although the intervention showed improvements among veterans, there was a high rate of attrition, meaning that many individuals did not continue use of the VetChange program. Clinicians might need to keep in touch with patients about their progress to help attend to any barriers and reinforce engagement and perceived benefit of any online program like VetChange.

- For scientists: Several of the noted limitations of this study design could be addressed in future research of this nature, including examining levels of comorbid symptoms and how those levels might influence participant engagement, the level of actual engagement or “dose” of the use of the online intervention, and more intensive effort to increase participant retention at follow-up. Because the VetChange intervention was developed among male participants and did not tailor aspects of any components to gender, there is a need for future qualitative research with women veterans to understand what they might seek in an online intervention. Additionally, these online interventions could be compared with similar technology-based interventions, but ones that work on enhancing peer-to-peer connections, as these could boost the positive outcomes for veterans in creating social capital.

- For policy makers: There needs to be increased attention to research and funding for this research to address co-occurring substance use and mental health issues among veterans. This research must address those individuals and groups with the potential to be marginalized within the armed services and examine what sorts of needs these stakeholders need to be supported as they return from active duty. These efforts should help ensure that our returning veterans are able to reintegrate successfully, live meaningful lives, and contribute as active members of our communities.

CITATIONS

Livingston, N. A., Simpson, T., Lehavot, K., Ameral, V., Brief, D. J., Enggasser, J., … & Keane, T. M. (2021). Differential alcohol treatment response by gender following use of VetChange. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 221, 108552. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108552