For people in treatment, who engages with recovery residences, and does it boost retention?

Residing in recovery residences, also called sober homes or halfway houses, improves substance use outcomes. Greater understanding of how recovery residences link people to other services can inform public health recommendations and recovery residence standards. This study examined people in treatment to examine predictors of living in recovery housing, and whether living in these venues equals boosted treatment retention.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Recovery residences are alcohol and other drug free living environments that provide peer support for those seeking recovery from substance use disorder. Recovery residences very greatly in terms of their structure and the support they offer, ranging from self-run homes that do not include any professional services, through to homes that have licensed clinical services, and may be housed within larger institution or organization.

Despite encouraging findings suggesting recovery housing reduces relapse risk and provides important recovery resources (e.g., stable housing; social support), most research to date has been on self-run recovery residences, and it is not yet well understood how recovery housing might influence retention in outpatient treatment. This is an important knowledge gap to address because understanding how recovery houses may support or hinder formal treatment engagement would inform provider and patient decision making around these recovery resources.

This study, utilizing both qualitative and quantitative assessment approaches, sought to identify the reasons individuals in outpatient substance use disorder treatment may use treatment-affiliated recovery housing. The researchers also sought to examine demographic, clinical, and service use differences among clients who utilize recovery housing, versus those who do not. In addition, they explored whether utilizing recovery housing during outpatient treatment is associated with increased odds of satisfactory discharge from care and longer lengths of time in outpatient treatment. Lastly, they conducted a focus group to explore recovery house residents’ reasons for choosing recovery housing.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was an observational study with data derived from 980 patient records at an outpatient addiction clinic located in a large, metropolitan area in the United States Midwest. On hundred and eighty-three (nearly 15%) of these patients were also residing in the outpatient clinic’s recovery house. The researchers sought to determine whether individuals who opted to live in recovery housing during outpatient treatment differed from those who did not, in terms of demographic, clinical, and service use factors. They also examined differences between these two groups with respect to outpatient program discharge status (i.e., were they discharged from treatment with or without staff approval) and length of stay in outpatient treatment.

In a qualitative component of the study, using in-depth group interviews, the researchers explored what individuals who were living in the recovery house were hoping to gain from the experience. These in-depth focus group discussions covered three primary topic areas: 1) Factors that influenced the decision to move into the recovery residence; 2) perceived challenges and benefits of this; and 3) the perceived role of recovery housing, more generally, in improving outcomes.

The outpatient treatment program offered two levels of care, ‘day treatment’ (otherwise known as partial hospitalization; 6 hours per day, Monday-Friday) and intensive outpatient (IOP; 3 hours per day, Monday-Thursday), with onsite recovery housing available as an additional option to patients in either of these two levels of care. Both these outpatient treatment tracks offered a mix of motivational interviewing techniques, cognitive behavioral approaches, and contingency management, but were primarily Twelve-Step Facilitation focused – a manualized therapy designed to help people abstain from alcohol and other drugs by systematically linking them to, and encouraging them to participate in, community-based, 12-step mutual-help organizations.

The program’s recovery residence was located in a separate area of the building where outpatient treatment was provided. Staff discussed the recovery housing option with all patients as part of the intake process and individuals could initiate or end recovery housing at any point of their outpatient treatment. Recovery housing programming included topic-specific group sessions designed to assist residents in strengthening sober living skills, establish new routines, practice relapse prevention strategies, and focus on transition planning to address potential barriers to healthy recovery.

Treatment record analysis:

The researchers obtained de-identified patient records for individuals admitted to the treatment program between January 2017 and December 2018. In addition to demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, race/ ethnicity, age, and educational attainment), the researchers created variables to examine dimensions of service need and service use. Using patient diagnosis records, they also created patient diagnosis summary variables from the diagnosis codes in the patient record (number of physical health diagnoses; number of mental health diagnoses; number of substance use disorder diagnoses), service use (total number of treatment episodes; total treatment locations; total number of treatment service types), treatment discharge status (with satisfactory discharge status reflecting discharge or transfer with staff approval, as well as conditional discharges with staff approval), and average length of stay in the outpatient treatment programs.

The researchers tested differences between those using and not using recovery housing with standard bivariate statistical tests (e.g., chi-square, t-tests). They also tested differences using logistic regression models to determine how much each factor increased or decreased the odds of patients using recovery housing. In addition to being tested separately, they entered factors found to be significantly associated with one another at the bivariate level, into a single logistic regression model to determine whether they were still significant when controlling for all other factors. Additionally, the researchers used logistic and linear regressions to test the relationships between recovery housing status, and outpatient discharge status and length of stay.

Focus groups:

The researchers created a focus group interview guide to cover three primary topic areas: 1) Factors that influenced the decision-making process to move into the structured sober living residence; 2) the perceived challenges and benefits to it; and 3) the role of recovery housing, more generally, in improving outcomes. The guide prompted residents to reflect on how they learned about the structured recovery residence and what made them think that moving into it was the best option for them.

Study sample:

Of the 980 clients who received services at the outpatient treatment program during the study period, about two-thirds of clients were men (65%), non-Hispanic White (87%), age 30 or older (68%), and had some sort of postsecondary education (89%). Forty-four percent of the sample had both alcohol and drug diagnoses in their records, and about half (52%) had more than two different types of diagnoses. The majority received only one episode of treatment (84%) at a single location (70%) and received an average number of 2.9 services per treatment episode. Roughly two-thirds (65.9%) had an average length of 87.5 days in the outpatient treatment program. One hundred and thirty-eight (14%) of the clients who entered outpatient treatment at the program during the study period also elected to live in the recovery residence. The majority (67%) of patients stepped down to a lower level of outpatient treatment after leaving the residence.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Women, younger people, and those with greater service utilization were more likely to utilize recovery housing.

When all individual characteristics were considered together in the same statistical model, the researchers found that outpatient program patients were 87% more likely to live in a recovery residence if they were female (vs. male) and have utilized more types of treatment services. Also, those living in the recovery residence were more likely to be younger, i.e., being in the less than 29 age-group, versus 30–39 or 40+ age categories.

Those living in recovery housing stayed in treatment longer and were more likely to complete treatment.

Those in recovery housing were on average in outpatient treatment 156.3 days while those receiving only outpatient treatment were in treatment 76.4 days, a statistically significant and substantial difference. Additionally, the patients living in recovery housing were also two times more likely to have a satisfactory discharge from the outpatient treatment, meaning staff felt were ready to finish the outpatient program when they left, versus leaving the program against clinical advice.

Recovery housing residents were seeking a safe and supportive living environment.

The majority of the participants in the focus group talked about being advised to move into a recovery residence upon completion of inpatient treatment. This advice and the decision to move into sober living, even if it was not explicitly recommended, stemmed from a recognition of relapse risk in their home environment, and that they needed additional support that could be provided in a sober living environment.

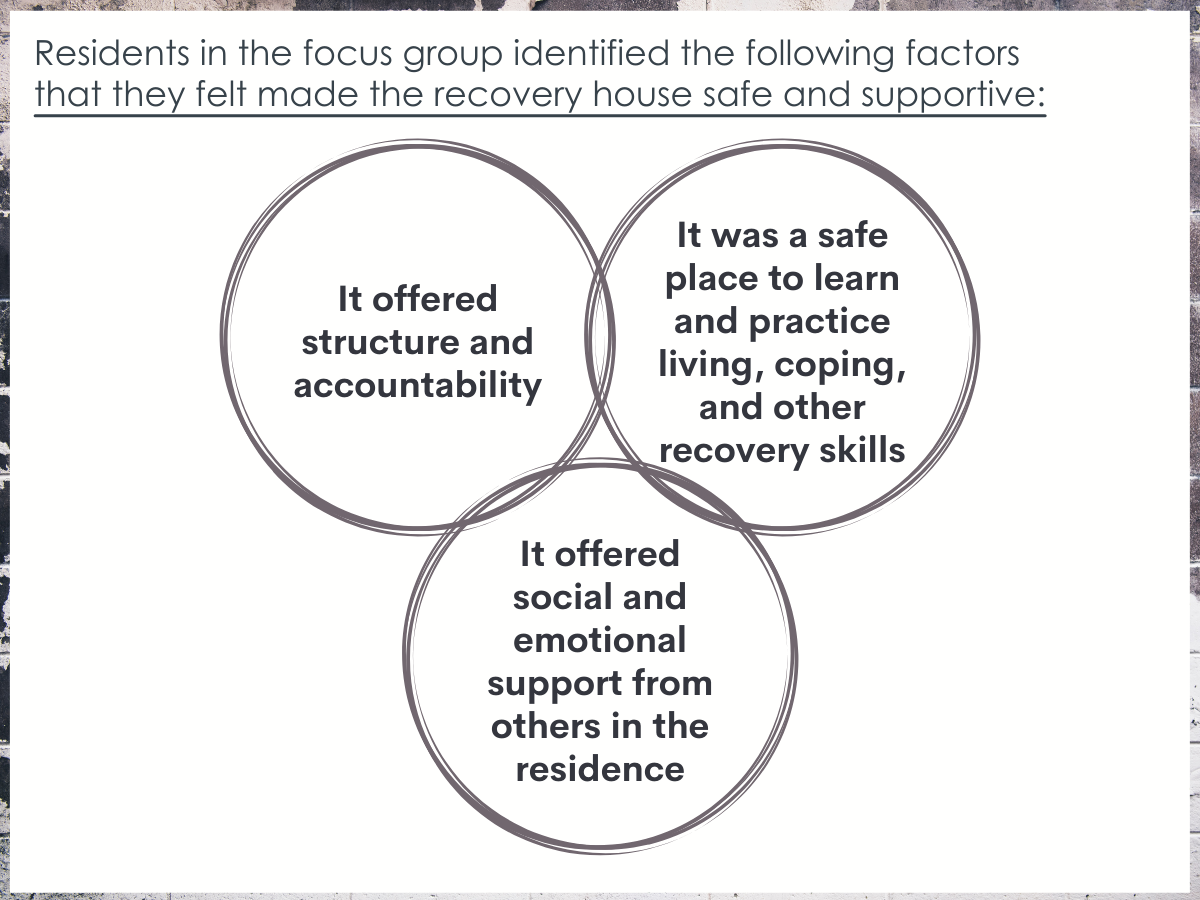

Residents in the focus group identified the following factors that they felt made the recovery house safe and supportive: 1) It offered structure and accountability; 2) it was a safe place to learn and practice living, coping, and other recovery skills; and 3) it offered social and emotional support from others in the residence.

Residents also identified some challenges associated with recovery housing.

Aside from the noted benefits of living in the facility, residents also reported some potential challenges. Two challenges most commonly reported were financial difficulties and the more general challenge of finding a recovery residence that was a good fit for them.

Some residents reported staying in other recovery residences prior to moving into this residence, however even those who had never lived in recovery housing before mentioned the importance of finding a residence that best suited their needs and felt comfortable.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Recovery residences are designed to be safe and supportive living environments that encourage recovery from substance use disorder and related problems. Recovery residences offer peer-based support for long-term recovery, often require a goal of abstinence, and some residences integrate professional support as well. There is a growing body of research showing recovery residencies are empirically supported continuing care options for substance use disorder.

Although recovery housing can be a useful and important step along the continuum of substance use disorder recovery care, many individuals do not utilize this resource. There are many reasons someone may choose not to live in recovery housing, including financial limitations (insurance rarely covers sober living environments) and social challenges. The researchers also noted that outpatients who elected to live in recovery housing were more likely to be younger, female, and have greater history of treatment utilization.

It is possible that younger people are more likely to live in recovery housing versus older people because youth is a time characterized by educational, social, and professional transitions younger (e.g., between high school and college, starting a career, not yet married, no dependents). In other words, younger adults may have made up the majority of residents because as a group they had more flexibility to live in a recovery residence than their older peers who may have had families they were supporting and jobs that made living in a recovery residence more challenging.

It is less clear why women may be more likely to have elected to use recovery housing than men. Women are more likely to be victims of sexual and physical abuse and some participants may have elected to live in safer recovery residences due to safety concerns elsewhere.

The fact greater treatment utilization was associated with greater likelihood of choosing recovery housing is potentially related to addiction severity. i.e., those who have greater service utilization are also most likely to have greater addiction severity and chronicity and be most needing of the additional support a recovery residence can provide.

Recovery house residents were found to be more likely to have what the researchers termed ‘satisfactory discharge from treatment’. In other words, they were more likely to finish up treatment at a time deemed appropriate by their providers, rather than leaving outpatient care against clinical advice. Also, recovery residents also spent more time in the outpatient program.

These findings might be expected given the extra structure and psychosocial support residents had, which may have served as a buffer against leaving outpatient treatment prematurely. Also, though not reported in the paper, it is possible that individuals living in the recovery house had greater overall motivation for change and greater addiction chronicity and severity (as evidenced by them having greater treatment history), and therefore were likely to stay in outpatient care for longer, as might have been recommended by their care team. Based on the design of this study, it can’t be known if living in the sober house led in a causal way to people staying in outpatient care longer.

Focus group participants noted a number of reasons for using recovery housing. Having a safe and supportive living environment was chief among these. This aligns with previous research showing this is a key determinant when individuals are deciding whether to live in recovery housing. This is also consistent with research on other recovery support services, where Twelve-Step Facilitation has been shown to produce better results than Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Motivational Enhancement Therapy for people with more drinkers in their social network. These folks with riskier social networks and environments may need/benefit more from structured, supportive spaces and people.

- LIMITATIONS

-

As noted by the researchers:

- Findings from this study are from one recovery residence in a Midwestern US state. How similar or different this setting may be to other recovery residences that may be used in conjunction with outpatient treatment is unclear.

- Residents’ characteristics were derived from administrative records, which limited the number of patient characteristics that could be explored. There are many factors not explored in this study that could influence the choice to live in a recovery residence, and outpatient treatment retention.

- Findings on the experiences of participants in the structured recovery residence represent one snapshot in time of those currently living in the residence.

Also:

- Cost and financial factors were not directly assessed. As such, it is unclear how participants’ financial situations may have influenced their choice to live in the recovery residence.

BOTTOM LINE

In this study, researchers found that people engaged in an outpatient addiction treatment program who also elected to live in recovery housing were more likely to be younger, female, and have greater history of treatment utilization. Also, compared to those who elected not to live in recovery housing, they remained in outpatient care for longer, and were more likely to be satisfactorily discharged from treatment. Recovery housing residents felt the structure and accountability, opportunity to learn coping and recovery skills, and access to social and emotional support from peers were most helpful.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Recovery residences support individuals by providing a safe living environment and readily available community of recovery-related social supports, and are associated with substantially better abstinence rates (vs. returning home immediately following residential treatment), greater rates of employment, and lower rates of criminal recidivism. The findings from this study also show an association between recovery housing and better outpatient treatment retention. When looking for a sober residence, past research has shown better outcomes for residences with larger organization affiliations (e.g., parent organizations; treatment facilities) and houses that implement a 12-step program.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Recovery residences support individuals by providing a safe living environment and readily available community of recovery-related social support, and are associated with substantially better abstinence rates, greater rates of employment, and lower rates of criminal recidivism. The findings from this study also show an association between recovery housing and better outpatient treatment retention. Taken together, the research on recovery residences speaks to their benefits for patients engaged in formal treatment and/or 12-step recovery. When seeking a sober residence, past research has shown better outcomes for residences with larger organization affiliations (e.g., parent organizations; treatment facilities) and houses that implement a 12-step program.

- For scientists: Recovery residences support individuals by providing a safe living environment and readily available community of recovery-related social support, and are associated with substantially better abstinence rates, greater rates of employment, and lower rates of criminal recidivism. The findings from this study also show an association between recovery housing and better outpatient treatment retention. At the same time, prospective experimental and quasi-experimental research is needed to better understand who, in particular, recovery residences are most likely to benefit, and how living in these environs influences formal treatment engagement (as an example, see Jason and colleagues work on Oxford Houses). Additionally, there is a need for more studies of the mechanisms through which these residences confer benefit in order to understand empirically what explains any recovery gains, (e.g., aspects of social support; employment; linkage to mutual-help programs).

- For policy makers: Recovery residences support individuals by providing a safe living environment and readily available community of recovery-related social support, and are associated with substantially better abstinence rates, greater rates of employment, and lower rates of criminal recidivism. The findings from this study also show an association between recovery housing and better outpatient treatment retention. Though recovery residences may represent a significant cost to individuals and healthcare systems, in the long-run they are a cost effective strategy because they end up saving individuals, healthcare systems, and society more broadly, money, because of the better recovery outcomes they support. Policies that support greater access to, and linkage with, recovery residences are warranted. In addition, policy makers should examine ways to fund recovery residence stays given the broader societal cost savings over the long-term.

CITATIONS

Mericle, A. A., Slaymaker, V., Gliske, K., Ngo, Q., & Subbaraman, M. S. (2022). The role of recovery housing during outpatient substance use treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 133, 108638. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108638