Both buprenorphine (Suboxone) and mutual-help groups increase the likelihood of achieving long-term opioid abstinence

For individuals with opioid use disorder, the opioid agonist medication buprenorphine-naloxone (often referred to by the brand name Suboxone) helps reduce opioid use and opioid-related overdose in the short-term. There remain important questions around Suboxone’s benefits over the long-term as well as what other treatment and recovery support services might enhance its benefits. Authors studied individuals with prescription opioid use disorder (e.g., oxycodone) over 3 ½ years to compare the long-term benefits of continued engagement with opioid agonist medications, mutual–help groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or Narcotics Anonymous (NA), and outpatient therapy on opioid abstinence.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

The opioid agonist medication Suboxone is a first-line treatment for opioid use disorder. Its positive effects on short-term outcomes – e.g., reduced overdose, decreased opioid use and increased opioid abstinence, and withdrawal symptom relief – are well documented. However, there is comparatively much less data on the long-term effects of opioid agonists. Furthermore, there are still unanswered questions about how agonists compare to other forms of substance use disorder (SUD) treatment, and if these other SUD treatment and recovery support services can be added to agonist treatment to enhance outcomes. In this study, authors used data from a large clinical trial to examine the long-term effects of opioid agonist medications, psychosocial interventions, and mutual–help meeting attendance (e.g., Narcotics Anonymous) on the natural course of achieving opioid abstinence over a 42-month follow-up period.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The study used data collected as part of a randomized clinical trial of Suboxone, initially examining 653 adults who met criteria for opioid use disorder based on their use of non-medical prescription opioids (i.e., oxycodone) collected from 10 sites across the United States. After completing the original trial, 338 participants were re-assessed at 18–, 30–, and 42–months after they entered the original study. They reported their current symptoms and diagnoses, as well as use of pharmacotherapies, psychosocial interventions, and mutual-help group attendance. This approach allowed the authors to determine the naturalistic course of service engagement and abstinence, and the relationship between the two, over a 42-month (3 ½ year) period.

This study examined the effects of “current participation” in the three SUD services most commonly sought in this sample: opioid agonist treatment (e.g., methadone, Suboxone), mutual-help groups (e.g., AA, NA), and outpatient counseling (any SUD treatment including intensive outpatient programs) on abstinence at 18-, 30-, and 42-months after the initial study. Authors simply assessed whether individuals were engaged in the service (yes or no) at the time of follow-up and whether they were abstinent during the 30 days before each follow-up. They tested the unique effect of participation at each time point separately in each service, while at the same time controlling for the effects of the other services, as well as their treatment site and whether they were randomized to receive Suboxone or placebo during the initial clinical trial. They used this approach to try and examine, as best they could, whether participation in each individual service on its own caused improved abstinence rates even if a person was engaged in another service.

As outlined in a prior study of the long-term sample of 375 individuals, when beginning the original clinical trial, participants were 33 years old on average, 44% female, and only 10% identified as a racial/ethnic minority (i.e., non-White). Regarding their clinical substance use histories, in their lifetimes 28% also met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol use disorder, 17% for cannabis use disorder, 31% for stimulant use disorder (e.g., cocaine), and 10% for sedative-hypnotic use disorder (e.g., benzodiazepines such as alprazolam, or Xanax as it is commonly known). They had been using opioids for 5 years on average, 32% had attended prior treatment for opioid use disorder (before the clinical trial), and 63% first used opioids to relieve pain. Regarding their mental health histories, in their lifetime 35% met DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder and 16% for posttraumatic stressor disorder (authors did assess other psychiatric disorders).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Utilization of one service was associated with utilization of other services.

At the three follow-up assessments, the majority of participants were engaged with one or more SUD services during the past year (61%-66%), with fewer receiving current treatment (47%-50%). The most common service was opioid agonist medication (27-35%; vast majority were receiving Suboxone), followed by mutual help meetings (27%-30%) and outpatient counseling (18-23%).

Being in one SUD service made it more likely that someone was using the other services as well. For example, if someone was taking an agonist medication at month 18, they were 20% more likely to also be attending mutual-help groups and 29% more likely to be engaged in outpatient counseling than those not receiving agonist treatment.

Opioid agonist treatment and mutual–help group participation each independently increased odds of abstinence while outpatient counseling did not.

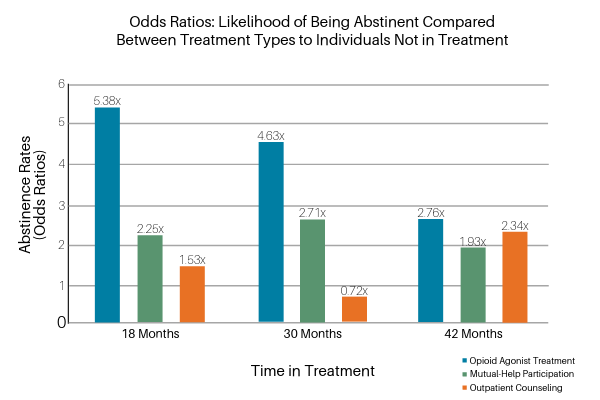

Opioid agonist medication had the largest effect on abstinence across each of the time points after controlling for the effects of mutual-help and outpatient counseling (see Figure 1 below). Those taking opioid agonist medication at the 18-month follow-up were 5 times more likely to be currently being abstinent than those not taking agonists independent of the effects for mutual-help and outpatient counseling. There was a similar pattern at the other follow-up assessments, such that participants taking agonist medications at 18 months were 4.5 times more likely to be abstinent at 30 months and 3 times more likely to be abstinent at 42 months.

Mutual-help group participation was also independently related to opioid abstinence. Participants who reported attending mutual-help groups like AA or NA at the 18-month follow-up were 2 times more likely to be abstinent compared to those who did not attend such groups, independent of the effects for agonist medications and outpatient counseling. Similarly, mutual-help group attendance at month 30 was associated with nearly 3 times greater likelihood of abstinence, and at attendance at month 42 was associated with 2 times greater likelihood of abstinence. In contrast to the effects of agonist treatment and mutual–help attendance, outpatient counseling was not associated with opioid abstinence at any of the follow-up periods after accounting for the effects of agonist treatment and mutual–help groups.

Importantly, using more than one of the treatments simultaneously neither enhanced nor detracted from the other (i.e., there were not statistical interaction effects between any of the treatments on opioid abstinence). In other words, for those taking opioid agonist medication, also attending mutual-help neither enhanced nor detracted from the beneficial effects of the agonist medications or vice–versa.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Of the three treatments examined, opioid agonist treatment and mutual-help groups were each significantly and independently associated with abstinence at 18-, 30-, and 42-month follow-ups. In contrast, outpatient counseling was not associated with abstinence at any time point. It is important to note that outpatient counseling was the least–utilized SUD service (roughly 20% or less at any follow-up point). This makes it hard to truly determine its effect on long-term abstinence when compared to more commonly used services like agonist treatment and mutual-help group attendance. In addition, given that many outpatient counseling programs encourage individuals to attend mutual-help groups, any effect of counseling participation on positive outcomes may be explained by mutual-help attendance – thus counseling would not offer any unique benefits but would be helpful in as much as counseling facilitated mutual-help participation or linked individuals to agonist medication services. Importantly, the benefits of agonist medication and mutual-help were additive, independent, and did not detract from (or enhance) effects of the other.

Taken together, these findings suggest that continued engagement in treatment, optimally opioid agonist medication plus mutual-help group attendance, provides the greatest chance to achieve long-term abstinence for individuals with prescription opioid use disorder. Previous research has found support for mutual-help groups as useful adjuncts in the treatment of other substance use disorders (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous for persons with AUD), although less has been written about mutual-help groups in the context of treating non-heroin–based opioid use disorders. This study shows benefit from mutual-help group attendance promote long-term abstinence for those with opioid use disorder. These findings need to be contextualized alongside other research showing that for those taking Suboxone and attending NA in particular, they may interact with individuals who have negative attitudes toward agonists, believing individuals cannot be “truly abstinent” while taking such medications, a view documented in NA’s written materials. Accordingly, more research is needed to better understand how to help individuals taking agonist treatment benefit from mutual-help group attendance, via work to overcome potentially negative agonist messages in NA, or to attend other, more agonist-friendly organizations.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Only 57% of the larger study was used in the current study, and for logistical reasons, their self-reported opioid use could not be validated by urine toxicology data.

- The study analyses did not include more specific information about SUD service utilization, only whether they were current participants. For example, they did not account for the type of agonist treatment in which participants were engaged (e.g., any adjunctive psychotherapy) or their level of adherence, meaning to what degree they followed their doctor’s recommendations. Analyses also did not include information pertaining to the types of meetings participants attended, frequency of attendance, use of a sponsor, and other reasons for self-selecting into (or out of) various mutual–help groups. These limitations are also relevant to participants’ outpatient counseling, as analyses did not include information regarding the type of counseling (e.g., empirically-supported approaches) or frequency. More specific information on agonist medication, mutual-help group, and outpatient counseling engagement would help to fully understand their potential contributions to long-term abstinence for those with opioid use disorder.

- Although abstinence and self-reported SUD service participation were assessed 3 times over a 42-month period, analyses tested their relationships at the same point in time. Therefore, it is still possible that the association between service engagement and abstinence was not causal. As authors mentioned, it is possible that individual factors such as abstinence motivation may be associated with more service engagement as well as long-term abstinence – thus explaining why service engagement was related to abstinence. It is also possible that there exist reciprocal relationships between service engagement, abstinence, motivation, and other variables that more fully explain the association between type of treatment and abstinence. In order to flesh out these complex relationships, future research should test the prospective effects of service engagement on outcomes – e.g., effects of engagement at 18-month follow-up on 21-month outcomes, 21-month engagement on 24-month outcomes, etc.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study showed that opioid agonist medications such as Suboxone are associated with substantially increased likelihood of long-term abstinence from prescription opioids (e.g., oxycodone). Similarly, mutual-help group attendance was associated with marked increases in long-term opioid abstinence. This is important because both options come with their misconceptions. Many members of 12-step mutual-help groups, especially Narcotics Anonymous (NA), see individuals taking opioid agonist medications as not “truly abstinent,” a view documented in NA’s written materials. In contrast, AA’s written materials suggest that medication choices are between a person and their physician. While more research is needed to flesh out the best ways for individuals taking agonist medications to engage with community-based mutual-help groups, this study suggests individuals give themselves the best chance of long-term abstinence via engagement in both services.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study showed that opioid agonist medications such as Suboxone are associated with substantially increased likelihood of long-term abstinence from pharmaceutical opioids (e.g., oxycodone). Similarly, mutual-help group attendance was associated with marked increases in long-term opioid abstinence. This is important because both options come with their misconceptions. Many members of 12-step mutual-help groups, especially Narcotics Anonymous (NA), see individuals taking opioid agonist medications as not “truly abstinent,” a view documented in NA’s written materials. In contrast, AA’s written materials suggest that medication choices are between a person and their physician. Evidence suggests that those with primary drug use disorders achieve similarly strong abstinence rates whether they attend NA or AA. Understanding these nuances is important for treatment providers. A recent survey found that a considerable percentage (30%) of individuals receiving agonist treatment were worried about encountering negative attitudes related to being prescribed agonists, and only 33% reported their provider discussed this with them prior to attending a meeting. Patient outcomes may be improved with thoughtful conversation about what type of community-based recovery support services will best meet their individual needs.

- For scientists: This naturalistic study showed that opioid agonist medications such as Suboxone are associated with substantially increased likelihood of long-term abstinence from prescription opioids (e.g., oxycodone). Similarly, mutual-help group attendance was associated with marked increases in long-term opioid abstinence as well. More research is warranted to understand how disclosing opioid agonist medication status at 12-step meetings, where agonist medication use may be discouraged, impacts meeting attendance, active involvement, and ultimately, substance use outcomes. Importantly, while the absence of effect for outpatient counseling may appear to imply that it was not effective, closer examination suggests the study may have been underpowered to detect a counseling effect given the small number of individuals that reported current counseling. Furthermore, 12-step facilitation is a key aspect of many outpatient psychosocial treatments and this overlap may have diluted any unique effects of outpatient counseling.

- For policy makers: This study showed that opioid agonist medications such as Suboxone are associated with substantially increased likelihood of long-term abstinence from prescription opioids (e.g., oxycodone). Similarly, mutual-help group attendance was associated with marked increases in long-term opioid abstinence. Attendance at mutual–help group meetings does not appear to impede buprenorphine treatment or vice–versa. Given that buprenorphine treatment and 12-step mutual-help groups are two evidence–informed approaches to addressing the opioid epidemic, funding research studies that examine these approaches in combination could help improve outcomes and reduce the public health burden of opioid use disorder.

CITATIONS

Weiss, R. D., Griffin, M. L., Marcovitz, D. E., Hilton, B. T., Fitzmaurice, G. M., McHugh, R. K., & Carroll, K. M. (2019). Correlates of opioid abstinence in a 42-month posttreatment naturalistic follow-up study of prescription opioid dependence. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 80(2). doi: 10.4088/JCP.18m12292