Culturally sensitive workshops that integrate traditional practices with motivational interviewing are well received, but don’t add benefit for Native American youth

Native American youth in the United States are subject to numerous health disparities, such as high rates of substance-related harms. However, to date, few evidence-based practices for improving substance use that respectfully integrate traditional cultural practices have been developed, evaluated, and implemented with urban Native American youth. The current study tested whether Native American youth who attend community wellness gatherings would receive an additional benefit related to reducing substance use from also attending an integrated motivational interviewing and native culture intervention. Results showed that the integrated intervention was well liked by participants, but engagement was low and substance use was no different between groups.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

The Native American population in the United States is subject to numerous health disparities, including high rates of substance use and related harms. Experts suggest these health disparities result from several interrelated, historical and ongoing experiences including but not limited to European contact, forced relocation, and cultural genocide, constituting widespread trauma and unresolved grief across generations. According to authors, programming that incorporates traditional practices, promotes community involvement, and encourages healthy notions of Native identity may increase well-being and healthy behaviors by ameliorating stress linked to cultural identity and stigma, as well as increasing community connections among urban Native Americans. However, few evidence-based programs that include these cultural elements have been developed, implemented, and evaluated with urban Native Americans. Thus, creating these types of programs has potential to help address the important health disparities experienced by Native youth. In this study, researchers tested whether Native youth that attend integrated motivational interviewing and native culture intervention workshops (MICUNAY) plus a community wellness gathering would exhibit better substance use outcomes compared to those that only attended the community wellness gatherings.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a randomized controlled trial of 185 urban dwelling (i.e., not living on a reservation) Native American youth between the ages 14-18. The study recruited urban Native American teens across northern, central, and southern California, USA from 2014 to 2017. Youth were assigned randomly to either attend monthly community wellness gatherings or MICUNAY workshops plus monthly community wellness gatherings. Teens had a three-month period to complete all three MICUNAY workshops. After completion of MICUNAY and/or the community wellness gatherings, teens then completed follow-up interviews three- and six-months after completing the workshops. At the beginning of the trial (i.e., baseline) and at each follow-up, the researchers assessed if youth used any substances and/or experienced any substance-related negative consequences over the previous three months. Additionally, the assessed youths’ intention to use substances over the next six months and how often the youth spent time around other teens that use substances.

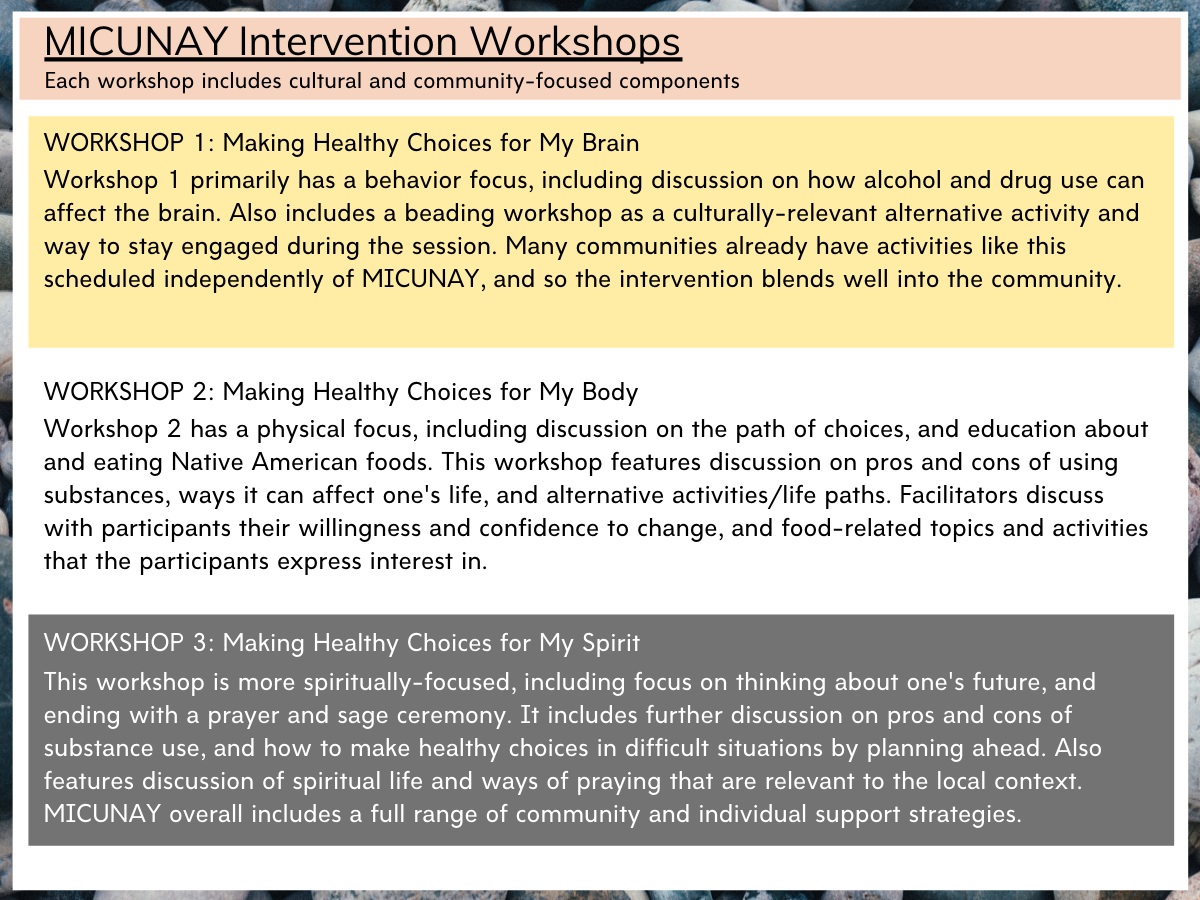

MICUNAY workshops were developed in close collaboration with Native American community partners, including extensive input from adolescents, parents, and tribal Elders. MICUNAY consisted of three workshops lasting two hours each that covered material on substance use, making healthy choices, and traditional Native American practices.

Figure 1.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Despite the MICUNAY intervention being developed with Native American community leaders and youth and seeming well-liked, it largely failed to attract and engage teens in the intervention and did not produce the anticipated benefits in terms of reducing teen substance use.

The MICUNAY group had a low engagement rate with only 57% of that sample attending all three workshops and 18% attending no workshops. This lack of attraction and engagement by youth is surprising given that the intervention was designed with input from Native elders and youth in order to maximize cultural sensitivity. This speaks to the perennial challenge of engaging teens in any kind of health behavior intervention regarding substance use and could have contributed to the lack of significant differences between the groups.

Rates of use for the overall sample remained stable over time with 23% of the sample reporting alcohol use in the past three months at baseline, and 30% of the sample reporting use at six months. Similarly, for marijuana, 28% of the sample reported use in the past three months at baseline, and 29% reported use in the past three months at the six-month follow up. Intentions to drink and use marijuana were also stable for the overall sample over the course of the study, as was the time that teens spent with peers who used alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana. Of note, tobacco use for the overall sample appeared to increase over time, as did the number of teens reporting consequences from drinking or marijuana. However, there were not meaningful differences between the treatment (integrated workshops plus wellness gathering) and control (wellness gathering only) on any of these outcomes.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study is one of the first large scale substance use prevention randomized clinical trials to be conducted with urban Native American adolescents across the state of California. This study compared two culturally based interventions for 185 urban Native American adolescents age 14-18 located in California. Intervention content, materials, and overall study design were developed with extensive community input to ensure cultural appropriateness, feasibility, and sustainability of the intervention, as well as a culturally acceptable control condition. The researchers did not find significant differences between the community wellness gathering only group and the integrated intervention (i.e., MICUNAY) plus community wellness gathering group on adolescents’ intentions to use, time spent with peers who use, personal use, or consequences. In fact, it was difficult to engage teens in the intervention (only 57% attended all three workshops and almost one in five teens attended zero workshops).

Rates of substance-related outcomes remained relatively stable over the course of the study for teens in both groups. This contrasts with previous research showing that adolescents typically increase their substance use during this developmental timeframe. It may be that connecting urban Native American teens to culturally centered activities and resources is protective, which has been shown in other work with this population. Given that both interventions included cultural components, it is possible that participants who had the opportunity to engage in either condition may have benefitted from exposure to activities emphasizing cultural education. That is, it may be that attending even one community wellness gathering offered an opportunity for the teens to connect or reconnect with their heritage. This is important to recognize since over the last decade Native American traditional practices have gained increasing recognition as a crucial component in addressing health disparities among this population.

Of note, despite challenges in terms of engaging youth and producing substance-related outcome benefits, the overall response to the integrated intervention was extremely positive, and several communities continue to implement the workshops as part of their programming for adolescents. This suggests there may be unmeasured aspects of the MICUNAY intervention that was appreciated by the community beyond those assessed in this study. This study represents a first step in understanding the effects of evidence-based prevention programming and traditional practices among urban Native American youth and highlights the continuing challenge of how best to engage teens in an intervention that may ultimately help mitigate substance-related harms. This is important given few evidence-based interventions have been successfully implemented with Indigenous communities.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Given the nature of the sample and extensive input from California Native American community members, the conclusions may not be generalizable outside of California.

- The MICUNAY group had a low engagement rate with only 57% of that sample attending all three workshop and 18% attending no workshops. This could have contributed to the lack of significant differences between the groups.

- Motivational interviewing fidelity ratings were quite variable. Thus, group leaders’ range of motivational interviewing skill may have impacted the outcomes.

- The groups were not matched on important substance related variables, possibly contributing to a range of experiences, and possibly affecting the efficacy of the intervention. For example, despite randomization, the community wellness gatherings only group was comprised of significantly more female adolescents (69% female) than the MICUNAY group (41% female).

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: The current study tested whether Native youth who attend community wellness gatherings would receive added benefit on their substance use over six-months from also attending an integrated motivational interviewing and native culture intervention (MICUNAY). Results found relatively low rates of treatment engagement by teens despite the cultural sensitivity of the intervention and found no difference in substance-related outcomes between the more intensive versus less intensive interventions over time. This means that the motivational interviewing-based intervention, MICUNAY, did not provide any added benefit beyond what was conferred from attending the community wellness gatherings by themselves, which focused on helping youth connect with Native identity and traditional practices. Yet, substance use and related outcomes remained stable over the course of the study. The researchers speculate that given rates of substance use typically rise during this developmental period the fact that they remained stable over the six-month period was seen as somewhat of a success. Thus, it may be that connecting urban Native American teens to any kind of culturally centered activities and resources may be protective against substance use escalation. This finding is in line with others that show engagement in culturally relevant activities has positive impact of the lives of youth. Accordingly, finding ways to engage youth in some kind of culturally relevant activities has potential to promote healthy choice making, even if this is not addressed explicitly. This appears to be especially true for Native American youth given they have been historically disenfranchised.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: The current study tested whether Native youth who attend community wellness gatherings would receive added benefit on their substance use over six-months from also attending an integrated motivational interviewing and native culture intervention (MICUNAY). Results found relatively low rates of treatment engagement by teens despite the cultural sensitivity of the intervention and found no difference in substance-related outcomes between the more intensive versus less intensive interventions over time. This means that the motivational interviewing-based intervention, MICUNAY, did not provide any added benefit beyond what was conferred from attending the community wellness gatherings which focused on helping youth connect with Native identity and traditional practices. Yet, substance use and related outcomes remained stable over the course of the study. The researchers speculate that given rates of substance use typically rise during this developmental period the fact that they remained stable over the six-month period was seen as somewhat of a success. Thus, it may be that connecting urban Native American teens to some kind of culturally centered activity and resources regardless of their explicit focus may be protective for substance use escalation. This finding is in line with others that show engagement in culturally relevant activities has positive impact of the lives of youth. Accordingly, finding ways to engage youth in culturally relevant activities has potential to promote healthy choice making, even if this is not addressed explicitly. This appears to be especially true for Native American youth given they have been historically disenfranchised. Treatment facilities could potentially help their Native American patients by providing access to culturally appropriate community resources and activities for individuals and families from underrepresented backgrounds.

- For scientists: The current study tested whether Native youth who attend community wellness gatherings would receive added benefit on their substance use over six-months from also attending an integrated motivational interviewing and native culture intervention (MICUNAY). Results found relatively low rates of treatment engagement by teens despite the cultural sensitivity of the intervention and found no difference in substance-related outcomes between the more intensive versus less intensive interventions over time. The researchers speculate that given rates of substance use typically rise during this developmental period the fact that they remained stable over the six-month period was seen as somewhat of a success. Thus, it may be that connecting urban Native American teens to some kind of culturally centered activities and resources could be protective for substance use escalation. However, this remains an answered empirical question and further research is needed to tease apart. As noted, despite reporting that they liked MICUNAY, teens exhibited low engagement with the workshops. Despite a very well-conceived and orchestrated intervention that incorporated native community elders and teens the failure to attract, engage, and benefit Native American teenagers highlights the fact that much more work is needed to make prevention and interventions programs more attractive and engaging so that retention rates and treatment effects can be improved.

- For policy makers: The current study tested whether Native youth who attend community wellness gatherings would receive added benefit on their substance use over six-months from also attending an integrated motivational interviewing and native culture intervention (MICUNAY). Results found relatively low rates of treatment engagement by teens despite the cultural sensitivity of the intervention and found no difference in substance-related outcomes between the more intensive versus less intensive interventions over time. The researchers speculate that given rates of substance use typically rise during this developmental period the fact that they remained stable over the six-month period was seen as somewhat of a success. Thus, it may potentially be that connecting urban Native American teens to some kind of culturally centered activity and resources could be protective for substance use escalation. Accordingly, finding ways to engage youth in culturally relevant activities has potential to promote healthy choice making, even if this is not addressed explicitly. Ultimately it could provide a public health benefit to provide space and funding for community based cultural activities and gatherings to help alleviate important health disparities.

CITATIONS

D’Amico, E. J., Dickerson, D. L., Brown, R. A., Johnson, C. L., Klein, D. J., & Agniel, D. (2020). Motivational interviewing and culture for urban Native American youth (MICUNAY): A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 111, 86-99. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.12.011