l

Substance use is the biggest risk factor for disease and disability among teens and young adults. There are, however, a range of empirically-supported treatments that reduce use and use-related consequences. One meta-analysis—a study of many studies— found that brief alcohol interventions featuring motivational interviewing, in particular, reduced alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems for adolescents and young adults. Another meta-analysis found that adolescents in almost all types of outpatient treatment had improvements, with the largest found for those in family therapy (e.g., multidimensional family therapy) and mixed/group counseling (e.g., “talk therapy”). Yet, many people do not complete treatment, especially young people. Helping individuals finish treatment once they start is important for several reasons, including receiving a full “dose” to develop skills and make links to community resources, and to help transition to a continuing care plan after treatment, which is key to sustaining treatment gains over time.

Young people can be especially hard to engage and retain in treatment. In one large study with over 300,000 cases and using SAMHSA’s Treatment Episode Data Set, only 50% of 89,000 young adults aged 18-24 who started substance use treatment completed it, with lower completion rates than older counterparts in both residential and outpatient settings. However, existing studies of treatment completion rates focused on samples in the United States and do not include adolescents. The current study investigated how demographic and clinical characteristics of adolescents and young adults in New South Wales, Australia were connected to completing community-based and residential substance use treatment.

This cross-sectional study was a retrospective analysis of routinely collected health information in residential and community-based substance use treatment services in New South Wales, Australia. New South Wales is a state on the east coast of Australia, and Sydney (the most populous city in Australia) is its capital. Non-government substance use treatment organizations that receive government funding submit information surrounding service provision, demographics, and clinical severity to the Network of Alcohol and Other Drug Agencies (NADA) database. In New South Wales, 39% of publicly funded treatment agencies are in the non-government sector, and 219 services submitted data from July 2021 to June 2022. The data for this study is drawn from this database.

Adolescents (aged 10-17 years) and young adults (aged 18-24) with a treatment episode between 2012 and 2023 in the database were identified. Those with missing data on the reason for treatment cessation or primary drug of concern were excluded as well as those with a treatment length of less than 1 day. If an individual had multiple treatment episodes, only the most recent episode was included. A total of 17,474 individuals were included in the analysis.

The primary outcome of the study is treatment completion, a binary (yes/no) variable. If the reason listed for treatment cessation was “service completed” then they were assigned yes—treatment completed. All other reasons for treatment cessation were coded as no—treatment not completed. All the analyses are separated by age group (adolescent vs young adult) and type of treatment – either residential or community (i.e., outreach, home, and other non-residential settings). The study examined treatment completion in a multivariable model – that tests the unique variance in treatment completion accounted for by the variable, controlling for all other variables in the model. Services were also coded as “youth-specific” if they only provided treatment to clients under the aged 25. Clinical severity was measured using 3 previously validated scales of psychological distress, quality of life and satisfaction, and substance use severity and dependence.

There were 3,730 adolescents and 9,994 young adults that had a community-based treatment episode. About a half to two-thirds of adolescents and young adults were males (59% and 69%), non-Aboriginal/Torres strait islander (73% and 74%), had secure housing (79% and 77%), lived in a major city (62% and 61%), and were in youth-specific treatment service (86% and 51%). The average age of adolescents was 16, and the average age of young adults was 21. Among adolescents, the primary drug of concern was reported as cannabis (68%), alcohol (18%), psychostimulants (9%), benzodiazepines and sedatives (2%), inhalants (2%), and opioids (1%). Among young adults, the primary drug of concern was reported as cannabis (43%), psychostimulants (27%), alcohol (26%), opioids (3%), and benzodiazepines and sedatives (2%). Only 43% of adolescents and 30% of young adults with a community-based treatment episode had clinical severity data available.

There were 826 adolescents and 2,924 young adults that had a residential treatment episode. Most adolescents and young adults were males (54% and 71%), non-Aboriginal/Torres strait islander (60% and 72%), had secure housing (86% and 71%), and lived in a major city (65% and 55%). Nearly all (98%) were in a youth-specific service, but only 23% of young adults were (i.e., in a facility that catered to young adults and not adults in general). The average age of adolescents was 16, and the average age of young adults was 22. Among adolescents, the primary drug of concern was listed as cannabis (54%), psychostimulants (22%), alcohol (19%), benzodiazepines and sedatives (2%), and inhalants (2%). Among young adults, the primary drug on concern was reported as psychostimulants (45%), cannabis (29%), alcohol (18%), opioids (6%), and benzodiazepines and sedatives. Only 36% of adolescents and 31% of young adults with a residential treatment episode had clinical severity data available.

Importantly, 2,600 individuals were excluded from the study due to insufficient information regarding treatment completion or other key variables. Those excluded from the study had significantly lower rates of cannabis as their primary substance (46 vs. 33%) and significantly, but slightly, lower rates of having been referred from the criminal-legal system (20 vs. 15%). They were less likely to have attended a youth-specific program (56 vs. 35%).

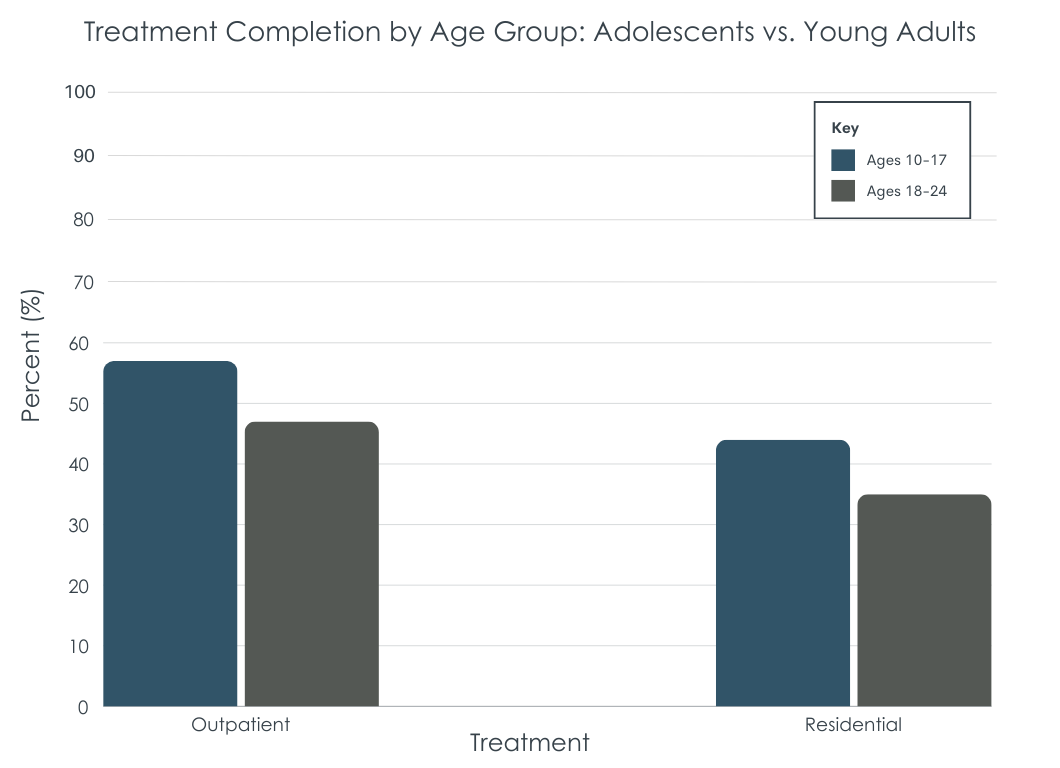

Most adolescents completed community-based treatment

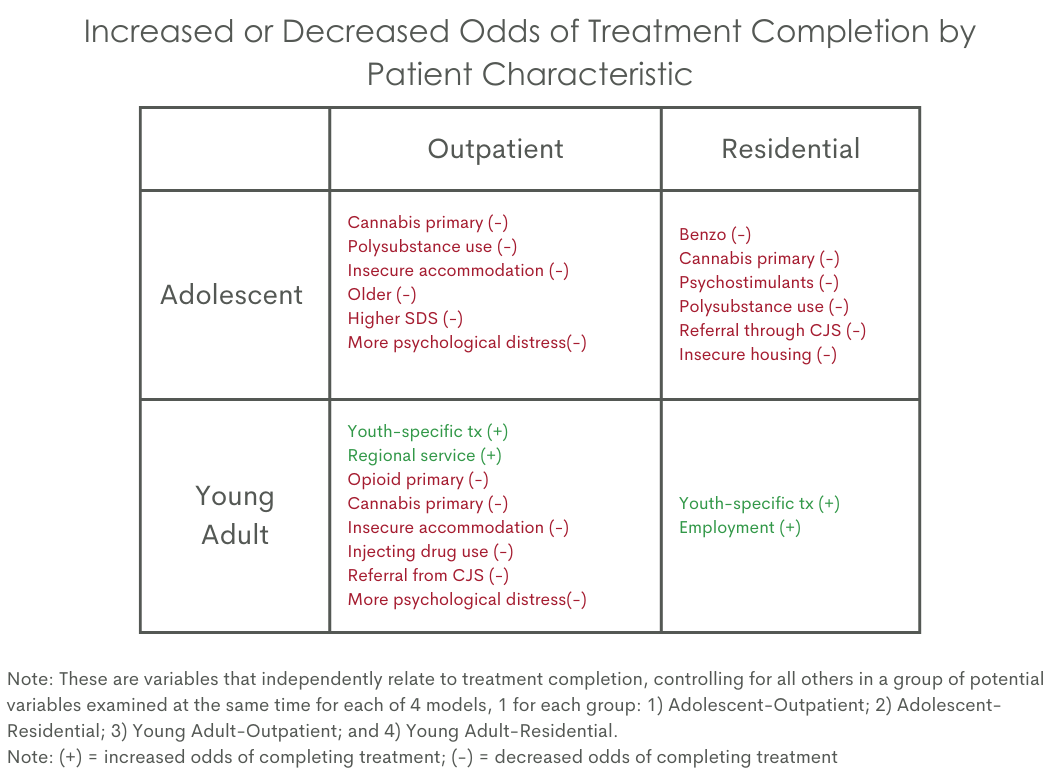

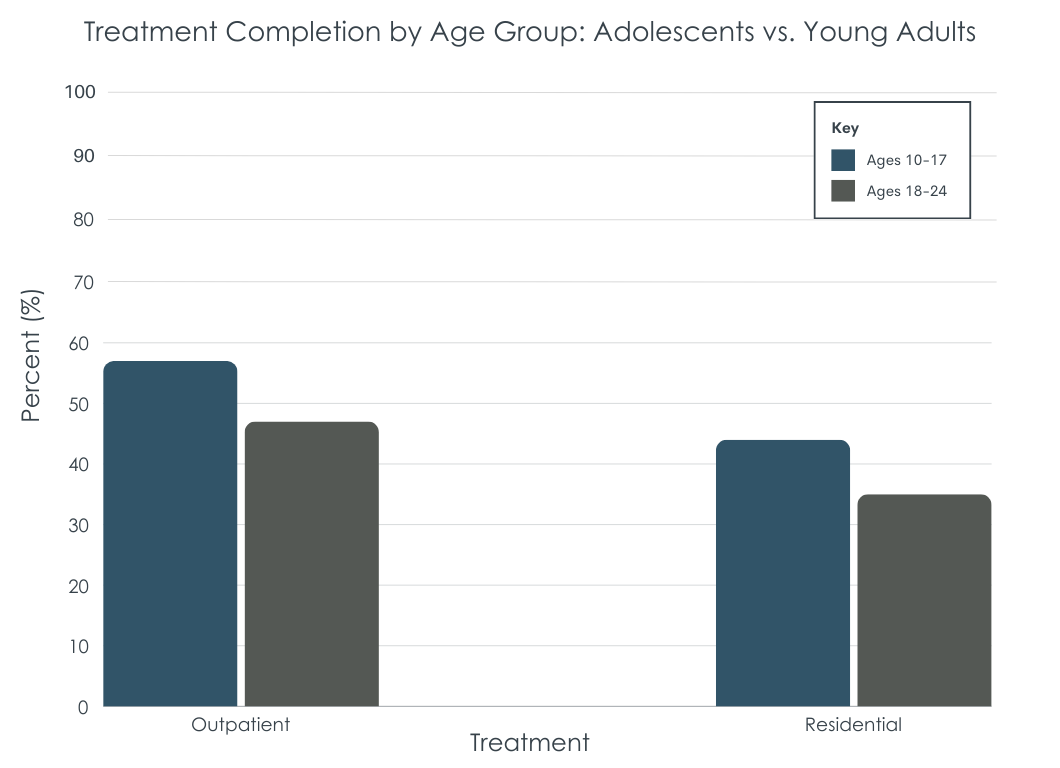

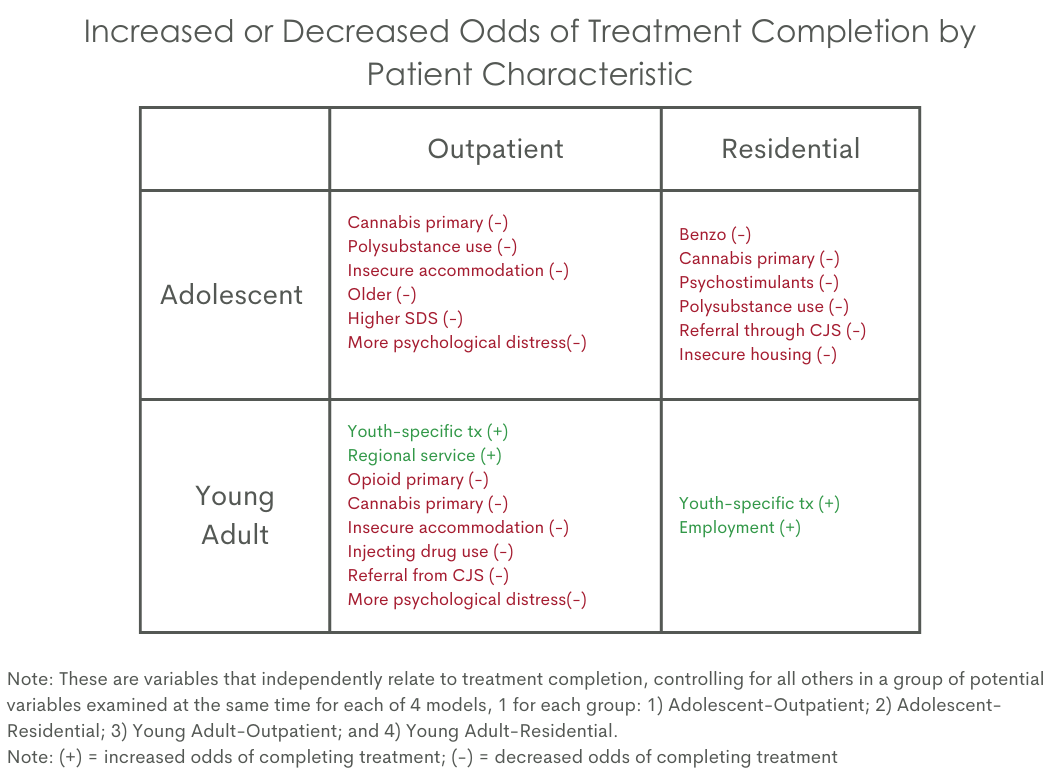

Only slightly over half (57%) of adolescents aged 10-17 years completed their community-based substance use treatment (see figure below). Several characteristics reduced the odds of treatment completion. Compared to adolescents that reported their primary substance as alcohol, those reporting cannabis as the primary substance of concern had 26% lower odds of treatment completion. Those reporting use of multiple substances, compared to a single substance, had 29% lower odds of treatment completion. Insecure housing (39% lower odds) and being older (12% lower odds) were also linked to lower odds of treatment completion. Among adolescents with clinical severity data, greater substance use severity (6% lower odds for a one-unit increase in severity) and greater psychological distress (2% lower odds for a one-unit increase in distress) were associated with reduced odds of treatment completion. See chart below for details regarding factors associated with increased and decreased odds of treatment completion.

Most young adults did not complete community-based treatment

Roughly half (54%) of young adults aged 18-24 did not complete community-based treatment. Young adults that reported opioids and cannabis as the primary drug of concern had lower odds of treatment completion, 43% and 25% respectively, compared to those reporting alcohol as the primary concern. Use of multiple substances and injection drug use history were also associated with 30% and 16% lower odds of treatment completion. Insecure housing was associated with 23% lower odds of completion, and being referred to treatment from the criminal justice system was also tied to 15% lower odds of completion. Young adults that were in youth-specific treatment had 81% higher odds of treatment completion. Among those with clinical severity data, a one-unit increase in psychological distress was associated with 3% lower odds of treatment completion.

Most adolescents did not complete residential treatment

Less than half (44%) of adolescents completed residential treatment. Compared to adolescents that reported alcohol as the primary substance of concern, those that reported benzodiazepines and sedative, cannabis, and psychostimulants had 74%, 58%, and 64% lower odds of treatment completion. Reporting use of multiple substances was linked with 38% lower odds of treatment completion, as was being referred through criminal justice (56% lower odds) and having insecure housing (58% lower odds). No clinical severity measures among adolescents were related to residential treatment completion.

Most young adults did not complete residential treatment

Only 35% of young adults completed residential treatment. Young adult-specific treatment and employment were associated with 72% and 69% higher odds of treatment completion. However, no other characteristics, including clinical severity, were related to young adult residential treatment completion.

The results from this large retrospective analysis of medical records in New South Wales, Australia found that barely half of adolescents and young adults completed community-based treatment and that less than half of adolescents and young adults completed residential treatment. Identifying factors that may identify adolescent and young adults as needing additional supports could help reduce treatment dropout and substance use related consequences.

There were several characteristics linked with reduced odds of treatment completion. For example, cannabis (vs alcohol) and polysubstance use related to lower odds of community and residential treatment completion among adolescents and community-based treatment completion among young adults. Insecure housing was also tied to reduced odds of community-based and residential treatment completion among adolescents and community-based treatment completion among young adults. Measures of clinical severity were linked to lower odds of community-based treatment completion among adolescents and young adults, but they were not tied to residential treatment completion. Overall, youth with more psychosocial challenges are likely to have more difficulty completing treatment, overall, but especially in outpatient settings. Residential settings provide extra scaffolding and support which may help compensate for additional clinical risks. While this study did not examine treatment effects, residential settings may be better clinical fits for youth with more psychosocial challenges.

At the same time, youth-specific services, however, were linked to higher odds of community and residential treatment among young adults. This study did not examine reasons why youth-specific treatment may have boosted young adults’ odds of treatment completion. Though developmentally-sensitive approaches examined in other studies, too, show that young adults fare well in youth-specific services. It may be that adolescents are, by default, referred to adolescent programming. For young adults, however, referral to youth-specific programming could mean developmentally-sensitive treatment with same-aged peers rather than having to assimilate into treatment geared toward middle and older aged adults, who typically have had an accumulation of severe consequences over time and have different life-contexts and life-course related psychosocial risks.

It is important to point out the high number of excluded participants (n = 2600). Because these individuals tended to be less likely to have attended a youth-specific program, and because youth specific programming was related to increased odds of completion, at least among young adults, the rates of treatment dropout may have been underestimated – i.e., even more may have dropped out than indicated by the rates observed in the findings.

Treatment providers within the community and in residential services may encourage completion through a multipronged support plan that includes traditional behavioral interventions to address co-occurring mental health challenges as well as linking to key structures within the community that increase recovery capital (e.g., housing supports), all within youth-specific programming. Future research is needed to explore how additional individual-level factors (e.g., co-occurring disorders, income) and community-level factors (e.g., transportation, housing affordability) interacts to buffer or amplify the findings from this study.

Adolescent and young adult treatment completion ranged from 35% to 57%. The results highlighted how factors differed between adolescents and young adults as well as in community-based vs residential treatment. However, polysubstance use, insecure housing, and psychological distress generally decreased odds of treatment completion, while odds of completion for young adults specifically increased when attending treatment that was youth-specific. Future research is needed to investigate other important correlates of treatment completion such as treatment modality, income, and existing supports outside of treatment (e.g., affordable housing, employment) and novel strategies to prevent treatment dropout.

Wells, M., Kelly, P. J., Mullaney, L., Lee, M. L., Stirling, R., Etter, S., & Larance, B. (2024). Predictors of alcohol and other drug treatment completion among young people accessing residential and community‐based treatment: A retrospective analysis of routinely collected service data. Addiction, 119(10), 1813–1825. doi: 10.1111/add.16602.

l

Substance use is the biggest risk factor for disease and disability among teens and young adults. There are, however, a range of empirically-supported treatments that reduce use and use-related consequences. One meta-analysis—a study of many studies— found that brief alcohol interventions featuring motivational interviewing, in particular, reduced alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems for adolescents and young adults. Another meta-analysis found that adolescents in almost all types of outpatient treatment had improvements, with the largest found for those in family therapy (e.g., multidimensional family therapy) and mixed/group counseling (e.g., “talk therapy”). Yet, many people do not complete treatment, especially young people. Helping individuals finish treatment once they start is important for several reasons, including receiving a full “dose” to develop skills and make links to community resources, and to help transition to a continuing care plan after treatment, which is key to sustaining treatment gains over time.

Young people can be especially hard to engage and retain in treatment. In one large study with over 300,000 cases and using SAMHSA’s Treatment Episode Data Set, only 50% of 89,000 young adults aged 18-24 who started substance use treatment completed it, with lower completion rates than older counterparts in both residential and outpatient settings. However, existing studies of treatment completion rates focused on samples in the United States and do not include adolescents. The current study investigated how demographic and clinical characteristics of adolescents and young adults in New South Wales, Australia were connected to completing community-based and residential substance use treatment.

This cross-sectional study was a retrospective analysis of routinely collected health information in residential and community-based substance use treatment services in New South Wales, Australia. New South Wales is a state on the east coast of Australia, and Sydney (the most populous city in Australia) is its capital. Non-government substance use treatment organizations that receive government funding submit information surrounding service provision, demographics, and clinical severity to the Network of Alcohol and Other Drug Agencies (NADA) database. In New South Wales, 39% of publicly funded treatment agencies are in the non-government sector, and 219 services submitted data from July 2021 to June 2022. The data for this study is drawn from this database.

Adolescents (aged 10-17 years) and young adults (aged 18-24) with a treatment episode between 2012 and 2023 in the database were identified. Those with missing data on the reason for treatment cessation or primary drug of concern were excluded as well as those with a treatment length of less than 1 day. If an individual had multiple treatment episodes, only the most recent episode was included. A total of 17,474 individuals were included in the analysis.

The primary outcome of the study is treatment completion, a binary (yes/no) variable. If the reason listed for treatment cessation was “service completed” then they were assigned yes—treatment completed. All other reasons for treatment cessation were coded as no—treatment not completed. All the analyses are separated by age group (adolescent vs young adult) and type of treatment – either residential or community (i.e., outreach, home, and other non-residential settings). The study examined treatment completion in a multivariable model – that tests the unique variance in treatment completion accounted for by the variable, controlling for all other variables in the model. Services were also coded as “youth-specific” if they only provided treatment to clients under the aged 25. Clinical severity was measured using 3 previously validated scales of psychological distress, quality of life and satisfaction, and substance use severity and dependence.

There were 3,730 adolescents and 9,994 young adults that had a community-based treatment episode. About a half to two-thirds of adolescents and young adults were males (59% and 69%), non-Aboriginal/Torres strait islander (73% and 74%), had secure housing (79% and 77%), lived in a major city (62% and 61%), and were in youth-specific treatment service (86% and 51%). The average age of adolescents was 16, and the average age of young adults was 21. Among adolescents, the primary drug of concern was reported as cannabis (68%), alcohol (18%), psychostimulants (9%), benzodiazepines and sedatives (2%), inhalants (2%), and opioids (1%). Among young adults, the primary drug of concern was reported as cannabis (43%), psychostimulants (27%), alcohol (26%), opioids (3%), and benzodiazepines and sedatives (2%). Only 43% of adolescents and 30% of young adults with a community-based treatment episode had clinical severity data available.

There were 826 adolescents and 2,924 young adults that had a residential treatment episode. Most adolescents and young adults were males (54% and 71%), non-Aboriginal/Torres strait islander (60% and 72%), had secure housing (86% and 71%), and lived in a major city (65% and 55%). Nearly all (98%) were in a youth-specific service, but only 23% of young adults were (i.e., in a facility that catered to young adults and not adults in general). The average age of adolescents was 16, and the average age of young adults was 22. Among adolescents, the primary drug of concern was listed as cannabis (54%), psychostimulants (22%), alcohol (19%), benzodiazepines and sedatives (2%), and inhalants (2%). Among young adults, the primary drug on concern was reported as psychostimulants (45%), cannabis (29%), alcohol (18%), opioids (6%), and benzodiazepines and sedatives. Only 36% of adolescents and 31% of young adults with a residential treatment episode had clinical severity data available.

Importantly, 2,600 individuals were excluded from the study due to insufficient information regarding treatment completion or other key variables. Those excluded from the study had significantly lower rates of cannabis as their primary substance (46 vs. 33%) and significantly, but slightly, lower rates of having been referred from the criminal-legal system (20 vs. 15%). They were less likely to have attended a youth-specific program (56 vs. 35%).

Most adolescents completed community-based treatment

Only slightly over half (57%) of adolescents aged 10-17 years completed their community-based substance use treatment (see figure below). Several characteristics reduced the odds of treatment completion. Compared to adolescents that reported their primary substance as alcohol, those reporting cannabis as the primary substance of concern had 26% lower odds of treatment completion. Those reporting use of multiple substances, compared to a single substance, had 29% lower odds of treatment completion. Insecure housing (39% lower odds) and being older (12% lower odds) were also linked to lower odds of treatment completion. Among adolescents with clinical severity data, greater substance use severity (6% lower odds for a one-unit increase in severity) and greater psychological distress (2% lower odds for a one-unit increase in distress) were associated with reduced odds of treatment completion. See chart below for details regarding factors associated with increased and decreased odds of treatment completion.

Most young adults did not complete community-based treatment

Roughly half (54%) of young adults aged 18-24 did not complete community-based treatment. Young adults that reported opioids and cannabis as the primary drug of concern had lower odds of treatment completion, 43% and 25% respectively, compared to those reporting alcohol as the primary concern. Use of multiple substances and injection drug use history were also associated with 30% and 16% lower odds of treatment completion. Insecure housing was associated with 23% lower odds of completion, and being referred to treatment from the criminal justice system was also tied to 15% lower odds of completion. Young adults that were in youth-specific treatment had 81% higher odds of treatment completion. Among those with clinical severity data, a one-unit increase in psychological distress was associated with 3% lower odds of treatment completion.

Most adolescents did not complete residential treatment

Less than half (44%) of adolescents completed residential treatment. Compared to adolescents that reported alcohol as the primary substance of concern, those that reported benzodiazepines and sedative, cannabis, and psychostimulants had 74%, 58%, and 64% lower odds of treatment completion. Reporting use of multiple substances was linked with 38% lower odds of treatment completion, as was being referred through criminal justice (56% lower odds) and having insecure housing (58% lower odds). No clinical severity measures among adolescents were related to residential treatment completion.

Most young adults did not complete residential treatment

Only 35% of young adults completed residential treatment. Young adult-specific treatment and employment were associated with 72% and 69% higher odds of treatment completion. However, no other characteristics, including clinical severity, were related to young adult residential treatment completion.

The results from this large retrospective analysis of medical records in New South Wales, Australia found that barely half of adolescents and young adults completed community-based treatment and that less than half of adolescents and young adults completed residential treatment. Identifying factors that may identify adolescent and young adults as needing additional supports could help reduce treatment dropout and substance use related consequences.

There were several characteristics linked with reduced odds of treatment completion. For example, cannabis (vs alcohol) and polysubstance use related to lower odds of community and residential treatment completion among adolescents and community-based treatment completion among young adults. Insecure housing was also tied to reduced odds of community-based and residential treatment completion among adolescents and community-based treatment completion among young adults. Measures of clinical severity were linked to lower odds of community-based treatment completion among adolescents and young adults, but they were not tied to residential treatment completion. Overall, youth with more psychosocial challenges are likely to have more difficulty completing treatment, overall, but especially in outpatient settings. Residential settings provide extra scaffolding and support which may help compensate for additional clinical risks. While this study did not examine treatment effects, residential settings may be better clinical fits for youth with more psychosocial challenges.

At the same time, youth-specific services, however, were linked to higher odds of community and residential treatment among young adults. This study did not examine reasons why youth-specific treatment may have boosted young adults’ odds of treatment completion. Though developmentally-sensitive approaches examined in other studies, too, show that young adults fare well in youth-specific services. It may be that adolescents are, by default, referred to adolescent programming. For young adults, however, referral to youth-specific programming could mean developmentally-sensitive treatment with same-aged peers rather than having to assimilate into treatment geared toward middle and older aged adults, who typically have had an accumulation of severe consequences over time and have different life-contexts and life-course related psychosocial risks.

It is important to point out the high number of excluded participants (n = 2600). Because these individuals tended to be less likely to have attended a youth-specific program, and because youth specific programming was related to increased odds of completion, at least among young adults, the rates of treatment dropout may have been underestimated – i.e., even more may have dropped out than indicated by the rates observed in the findings.

Treatment providers within the community and in residential services may encourage completion through a multipronged support plan that includes traditional behavioral interventions to address co-occurring mental health challenges as well as linking to key structures within the community that increase recovery capital (e.g., housing supports), all within youth-specific programming. Future research is needed to explore how additional individual-level factors (e.g., co-occurring disorders, income) and community-level factors (e.g., transportation, housing affordability) interacts to buffer or amplify the findings from this study.

Adolescent and young adult treatment completion ranged from 35% to 57%. The results highlighted how factors differed between adolescents and young adults as well as in community-based vs residential treatment. However, polysubstance use, insecure housing, and psychological distress generally decreased odds of treatment completion, while odds of completion for young adults specifically increased when attending treatment that was youth-specific. Future research is needed to investigate other important correlates of treatment completion such as treatment modality, income, and existing supports outside of treatment (e.g., affordable housing, employment) and novel strategies to prevent treatment dropout.

Wells, M., Kelly, P. J., Mullaney, L., Lee, M. L., Stirling, R., Etter, S., & Larance, B. (2024). Predictors of alcohol and other drug treatment completion among young people accessing residential and community‐based treatment: A retrospective analysis of routinely collected service data. Addiction, 119(10), 1813–1825. doi: 10.1111/add.16602.

l

Substance use is the biggest risk factor for disease and disability among teens and young adults. There are, however, a range of empirically-supported treatments that reduce use and use-related consequences. One meta-analysis—a study of many studies— found that brief alcohol interventions featuring motivational interviewing, in particular, reduced alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems for adolescents and young adults. Another meta-analysis found that adolescents in almost all types of outpatient treatment had improvements, with the largest found for those in family therapy (e.g., multidimensional family therapy) and mixed/group counseling (e.g., “talk therapy”). Yet, many people do not complete treatment, especially young people. Helping individuals finish treatment once they start is important for several reasons, including receiving a full “dose” to develop skills and make links to community resources, and to help transition to a continuing care plan after treatment, which is key to sustaining treatment gains over time.

Young people can be especially hard to engage and retain in treatment. In one large study with over 300,000 cases and using SAMHSA’s Treatment Episode Data Set, only 50% of 89,000 young adults aged 18-24 who started substance use treatment completed it, with lower completion rates than older counterparts in both residential and outpatient settings. However, existing studies of treatment completion rates focused on samples in the United States and do not include adolescents. The current study investigated how demographic and clinical characteristics of adolescents and young adults in New South Wales, Australia were connected to completing community-based and residential substance use treatment.

This cross-sectional study was a retrospective analysis of routinely collected health information in residential and community-based substance use treatment services in New South Wales, Australia. New South Wales is a state on the east coast of Australia, and Sydney (the most populous city in Australia) is its capital. Non-government substance use treatment organizations that receive government funding submit information surrounding service provision, demographics, and clinical severity to the Network of Alcohol and Other Drug Agencies (NADA) database. In New South Wales, 39% of publicly funded treatment agencies are in the non-government sector, and 219 services submitted data from July 2021 to June 2022. The data for this study is drawn from this database.

Adolescents (aged 10-17 years) and young adults (aged 18-24) with a treatment episode between 2012 and 2023 in the database were identified. Those with missing data on the reason for treatment cessation or primary drug of concern were excluded as well as those with a treatment length of less than 1 day. If an individual had multiple treatment episodes, only the most recent episode was included. A total of 17,474 individuals were included in the analysis.

The primary outcome of the study is treatment completion, a binary (yes/no) variable. If the reason listed for treatment cessation was “service completed” then they were assigned yes—treatment completed. All other reasons for treatment cessation were coded as no—treatment not completed. All the analyses are separated by age group (adolescent vs young adult) and type of treatment – either residential or community (i.e., outreach, home, and other non-residential settings). The study examined treatment completion in a multivariable model – that tests the unique variance in treatment completion accounted for by the variable, controlling for all other variables in the model. Services were also coded as “youth-specific” if they only provided treatment to clients under the aged 25. Clinical severity was measured using 3 previously validated scales of psychological distress, quality of life and satisfaction, and substance use severity and dependence.

There were 3,730 adolescents and 9,994 young adults that had a community-based treatment episode. About a half to two-thirds of adolescents and young adults were males (59% and 69%), non-Aboriginal/Torres strait islander (73% and 74%), had secure housing (79% and 77%), lived in a major city (62% and 61%), and were in youth-specific treatment service (86% and 51%). The average age of adolescents was 16, and the average age of young adults was 21. Among adolescents, the primary drug of concern was reported as cannabis (68%), alcohol (18%), psychostimulants (9%), benzodiazepines and sedatives (2%), inhalants (2%), and opioids (1%). Among young adults, the primary drug of concern was reported as cannabis (43%), psychostimulants (27%), alcohol (26%), opioids (3%), and benzodiazepines and sedatives (2%). Only 43% of adolescents and 30% of young adults with a community-based treatment episode had clinical severity data available.

There were 826 adolescents and 2,924 young adults that had a residential treatment episode. Most adolescents and young adults were males (54% and 71%), non-Aboriginal/Torres strait islander (60% and 72%), had secure housing (86% and 71%), and lived in a major city (65% and 55%). Nearly all (98%) were in a youth-specific service, but only 23% of young adults were (i.e., in a facility that catered to young adults and not adults in general). The average age of adolescents was 16, and the average age of young adults was 22. Among adolescents, the primary drug of concern was listed as cannabis (54%), psychostimulants (22%), alcohol (19%), benzodiazepines and sedatives (2%), and inhalants (2%). Among young adults, the primary drug on concern was reported as psychostimulants (45%), cannabis (29%), alcohol (18%), opioids (6%), and benzodiazepines and sedatives. Only 36% of adolescents and 31% of young adults with a residential treatment episode had clinical severity data available.

Importantly, 2,600 individuals were excluded from the study due to insufficient information regarding treatment completion or other key variables. Those excluded from the study had significantly lower rates of cannabis as their primary substance (46 vs. 33%) and significantly, but slightly, lower rates of having been referred from the criminal-legal system (20 vs. 15%). They were less likely to have attended a youth-specific program (56 vs. 35%).

Most adolescents completed community-based treatment

Only slightly over half (57%) of adolescents aged 10-17 years completed their community-based substance use treatment (see figure below). Several characteristics reduced the odds of treatment completion. Compared to adolescents that reported their primary substance as alcohol, those reporting cannabis as the primary substance of concern had 26% lower odds of treatment completion. Those reporting use of multiple substances, compared to a single substance, had 29% lower odds of treatment completion. Insecure housing (39% lower odds) and being older (12% lower odds) were also linked to lower odds of treatment completion. Among adolescents with clinical severity data, greater substance use severity (6% lower odds for a one-unit increase in severity) and greater psychological distress (2% lower odds for a one-unit increase in distress) were associated with reduced odds of treatment completion. See chart below for details regarding factors associated with increased and decreased odds of treatment completion.

Most young adults did not complete community-based treatment

Roughly half (54%) of young adults aged 18-24 did not complete community-based treatment. Young adults that reported opioids and cannabis as the primary drug of concern had lower odds of treatment completion, 43% and 25% respectively, compared to those reporting alcohol as the primary concern. Use of multiple substances and injection drug use history were also associated with 30% and 16% lower odds of treatment completion. Insecure housing was associated with 23% lower odds of completion, and being referred to treatment from the criminal justice system was also tied to 15% lower odds of completion. Young adults that were in youth-specific treatment had 81% higher odds of treatment completion. Among those with clinical severity data, a one-unit increase in psychological distress was associated with 3% lower odds of treatment completion.

Most adolescents did not complete residential treatment

Less than half (44%) of adolescents completed residential treatment. Compared to adolescents that reported alcohol as the primary substance of concern, those that reported benzodiazepines and sedative, cannabis, and psychostimulants had 74%, 58%, and 64% lower odds of treatment completion. Reporting use of multiple substances was linked with 38% lower odds of treatment completion, as was being referred through criminal justice (56% lower odds) and having insecure housing (58% lower odds). No clinical severity measures among adolescents were related to residential treatment completion.

Most young adults did not complete residential treatment

Only 35% of young adults completed residential treatment. Young adult-specific treatment and employment were associated with 72% and 69% higher odds of treatment completion. However, no other characteristics, including clinical severity, were related to young adult residential treatment completion.

The results from this large retrospective analysis of medical records in New South Wales, Australia found that barely half of adolescents and young adults completed community-based treatment and that less than half of adolescents and young adults completed residential treatment. Identifying factors that may identify adolescent and young adults as needing additional supports could help reduce treatment dropout and substance use related consequences.

There were several characteristics linked with reduced odds of treatment completion. For example, cannabis (vs alcohol) and polysubstance use related to lower odds of community and residential treatment completion among adolescents and community-based treatment completion among young adults. Insecure housing was also tied to reduced odds of community-based and residential treatment completion among adolescents and community-based treatment completion among young adults. Measures of clinical severity were linked to lower odds of community-based treatment completion among adolescents and young adults, but they were not tied to residential treatment completion. Overall, youth with more psychosocial challenges are likely to have more difficulty completing treatment, overall, but especially in outpatient settings. Residential settings provide extra scaffolding and support which may help compensate for additional clinical risks. While this study did not examine treatment effects, residential settings may be better clinical fits for youth with more psychosocial challenges.

At the same time, youth-specific services, however, were linked to higher odds of community and residential treatment among young adults. This study did not examine reasons why youth-specific treatment may have boosted young adults’ odds of treatment completion. Though developmentally-sensitive approaches examined in other studies, too, show that young adults fare well in youth-specific services. It may be that adolescents are, by default, referred to adolescent programming. For young adults, however, referral to youth-specific programming could mean developmentally-sensitive treatment with same-aged peers rather than having to assimilate into treatment geared toward middle and older aged adults, who typically have had an accumulation of severe consequences over time and have different life-contexts and life-course related psychosocial risks.

It is important to point out the high number of excluded participants (n = 2600). Because these individuals tended to be less likely to have attended a youth-specific program, and because youth specific programming was related to increased odds of completion, at least among young adults, the rates of treatment dropout may have been underestimated – i.e., even more may have dropped out than indicated by the rates observed in the findings.

Treatment providers within the community and in residential services may encourage completion through a multipronged support plan that includes traditional behavioral interventions to address co-occurring mental health challenges as well as linking to key structures within the community that increase recovery capital (e.g., housing supports), all within youth-specific programming. Future research is needed to explore how additional individual-level factors (e.g., co-occurring disorders, income) and community-level factors (e.g., transportation, housing affordability) interacts to buffer or amplify the findings from this study.

Adolescent and young adult treatment completion ranged from 35% to 57%. The results highlighted how factors differed between adolescents and young adults as well as in community-based vs residential treatment. However, polysubstance use, insecure housing, and psychological distress generally decreased odds of treatment completion, while odds of completion for young adults specifically increased when attending treatment that was youth-specific. Future research is needed to investigate other important correlates of treatment completion such as treatment modality, income, and existing supports outside of treatment (e.g., affordable housing, employment) and novel strategies to prevent treatment dropout.

Wells, M., Kelly, P. J., Mullaney, L., Lee, M. L., Stirling, R., Etter, S., & Larance, B. (2024). Predictors of alcohol and other drug treatment completion among young people accessing residential and community‐based treatment: A retrospective analysis of routinely collected service data. Addiction, 119(10), 1813–1825. doi: 10.1111/add.16602.