Recovery without borders: The cross-cultural applicability of Narcotics Anonymous

Narcotics Anonymous (NA) is a nonprofessional, 12-step-based mutual–help organization with 70,065 meetings worldwide, of which 27,677 are in the USA. Somewhat surprisingly, Iran has seen the largest increase in NA meetings in the past 10 years. This study conducted a cross-cultural comparison of participation in the two countries with some unexpected results.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Narcotics Anonymous is a nonprofessional, mutual–help organization which promotes a 12-step model of recovery, including an abstinence goal. The NA World Services office reports 70,065 meetings in 139 countries as of 2019. Of these, 27,677 (40%) are in the United States. Given its free availability, NA is often a frontline resource for those looking to recover from a drug problem. NA has been found to be effective in studies where individuals are naturalistically followed over time as well as those where individuals are randomized to intensive 12 step-referral compared to less intensive, standard referrals. Emerging work also shows that, for individuals with opioid use disorder, NA and other 12-step mutual-help attendance may be helpful over and above opioid agonist medications like buprenorphine (often prescribed in formulation with naloxone and known by the brand name Suboxone).

NA was initiated in Iran in 1990 and has grown considerably since that time with 21,974 NA groups across the country. While aspects of Iranian members’ spiritual development and quality of life have been reported previously, there is little information regarding their demographics, substance use, and NA membership experience to–date. This is an important gap in our knowledge because understanding aspects of the NA program in Iran, an ‘‘Islamic Republic,’’ can helps us learn about the mechanisms underlying the adaptability of the NA format in promoting addiction recovery in cultural settings different from that in the U.S. With this goal in mind, the authors compared a sample of Iranian NA members to a sample of U.S. members on a host of demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender) as well as ways in which they participate in NA (e.g., use of sponsors) and related experiences (e.g., reduced craving).

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The authors used an onsite administered retrospective survey of U.S. and Iranian NA members (N=789), supplemented with interviews of NA leadership from both countries. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and reviewed for content by the authors to ascertain a consensus on the queries presented and responses. All were conducted in English with English-speaking subjects, requiring no translation. These data collection methods focused on the history and operation of NA, including meeting format, sponsorship activities, and relations with governmental and clerical figures. Specifically, study authors gathered information regarding participants’ first encounter with the fellowship; meeting attendance; sponsor/sponsee experiences; and questions related to spirituality, including religious practices, experience of God, and experience of spiritual awakening within NA as well as craving.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

This approach yielded total of 789 NA members across the two sites with 262 Iranian respondents that averaged 8.66 years (SD = 4.85) since last using drugs and 527 U.S. respondents that averaged 6.12 years (SD = 8.55) since last using drugs.

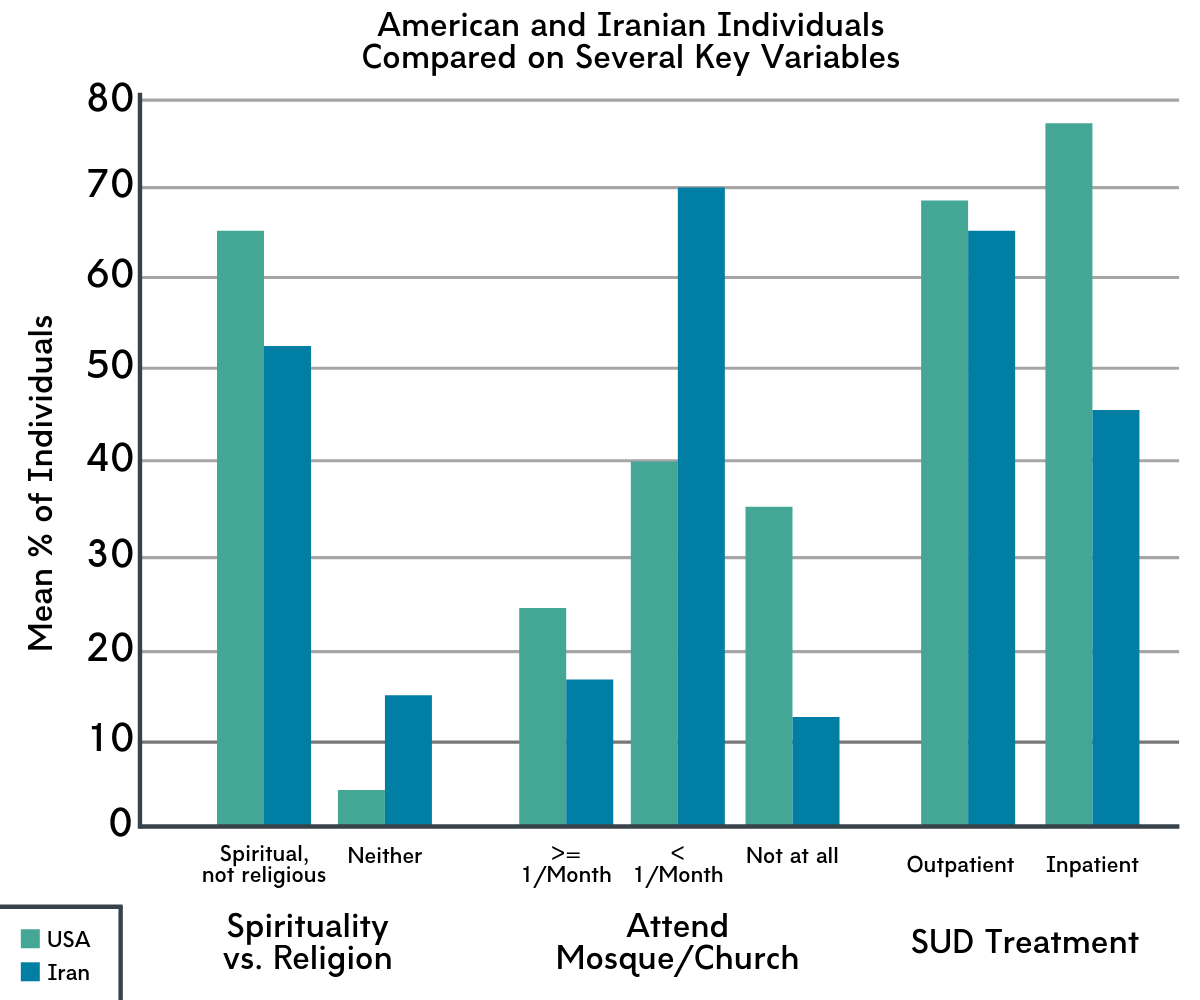

The Iranian sample was almost exclusively male; otherwise, there were only slight differences between the two samples in age, religiosity, and prior outpatient experience.

Relative to the U.S. respondents, the Iranian NA members surveyed were older, more likely male, more likely employed (or students), and less likely to have received prior treatment for their substance use disorder. Iranian respondents also identified less as being religious and were less likely to attend their respective formal place of worship (mosque vs. church). Iranian respondents were also less likely to experience drug craving.

Figure 1.

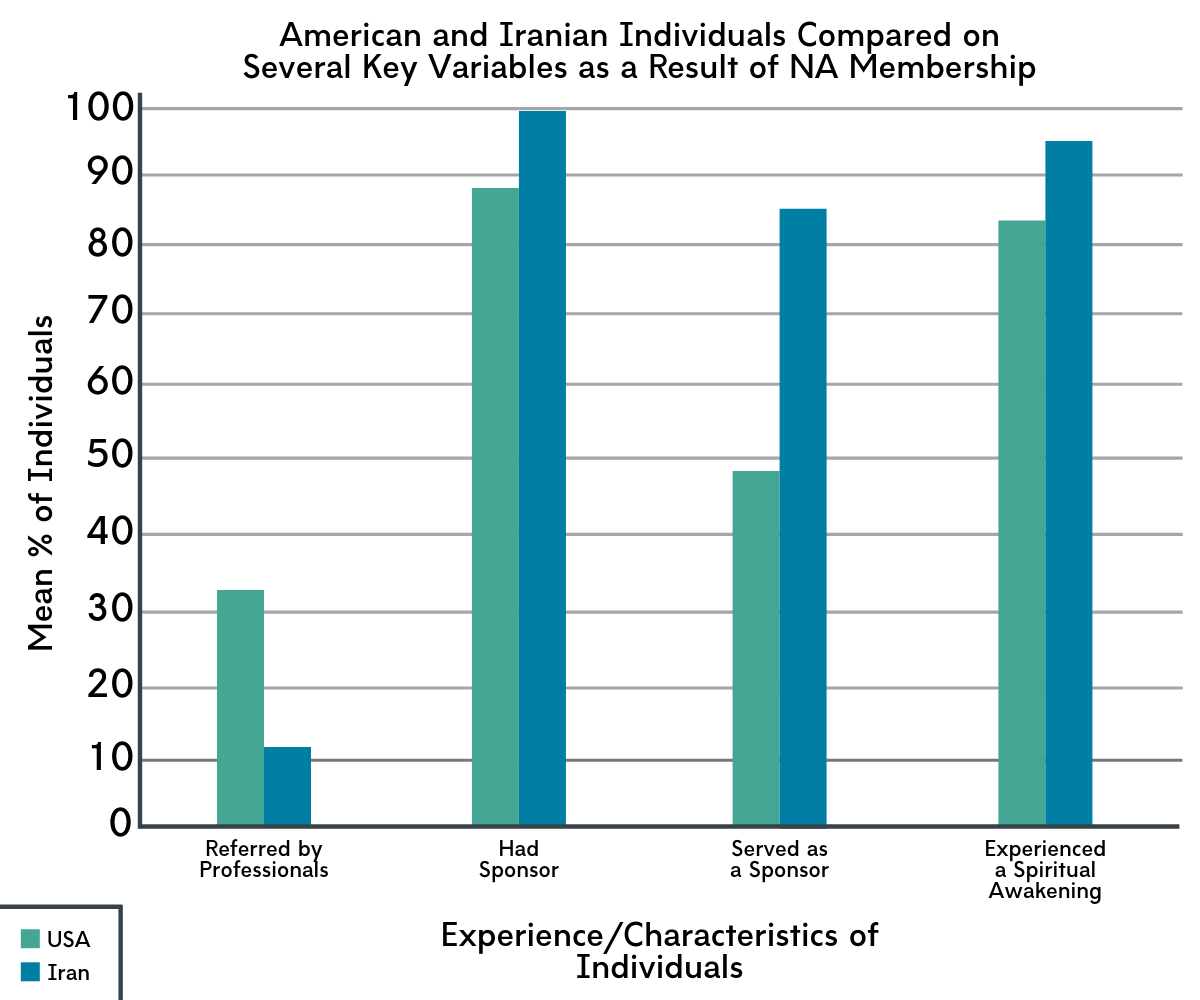

Iranian sample was more likely to have sponsor and serve as sponsors than the US sample.

Iranian respondents were more involved in social aspects of NA social than were U.S. members. The age at which Iranian respondents first attended an NA meeting was younger than American members, and they were less likely to have been referred to NA by a professional. The Iranian sample was more likely to have sponsor and serve as sponsors than the U.S. sample.

Figure 2.

Key aspects of NA membership experience in Iran differ from that of NA in the U.S.

Through in-depth interviews, authors found that in Iran, an active effort is made to reach out to persons who initially attend but then drop out, and ‘‘service commitments’’ (efforts used to maintain fellowship functions) are actively promoted from early on in membership. The format of sponsorship also differs from that typical in the U.S., in that sponsors may have as many as 30 or more sponsees, whereas more than 5 sponsees is unusual in the United States. This format arose because there were only a limited number of members with long-term recovery to serve in this role when the fellowship was first established in Iran. Additionally, sponsors frequently meet with sponsees as a group more than once each week to ‘‘work’’ the NA steps. This group ritual is in addition to the regular NA meeting format employed in the United States and in most settings worldwide. This emphasis on systematically ‘‘working’’ the steps is much more actively promoted in Iran than in the United States, and celebrations are held in Iran for groups of sponsees upon their completion of the 12 steps, in contrast with NA in other countries where abstinence anniversaries are celebrated.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Overall, the authors found that key aspects of the NA 12-step culture and format were transferrable to a different cultural setting. The fact that the 12-step fellowship, with its historically Judeo-Christian origins, can be adopted and sustained in a Muslim country is intriguing and significant. Findings suggest that key mechanisms of behavior change that promote recovery in this fellowship, namely the cohesiveness among members, ascription to the fellowship’s ideology, and the basic format of its group meetings, may be able to operate independent of the cultural setting where NA arose. These apparent mechanisms of behavior change may also be applicable to other recovery services, such as 12-step-oriented residential programs or recovery residences. Importantly, this study was a survey that assessed individuals at one time point (i.e., cross-sectional). Longitudinal research, where researchers measure individuals’ NA participation over time, and whether it predicts better outcomes, is needed to offer more solid conclusions about NA’s utility among Iranians with opioid and other drug use disorders. That said, observational evidence of its growth and staying power is one kind of evidence. It may translate eventually into clearer demonstration of NA’s clinical and public health utility for opioid addiction in Iran and potentially other countries. Though cross-sectional, the perceived utility of NA among Iranian members also speaks to the specific benefit afforded by free, community-based services where formal SUD treatment is less available, as is the case in Iran. Additionally, expanding the established NA format with the sponsor-led meetings, as developed in Iran, may be a useful innovation in the U.S.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Access to NA members in Iran was limited to 2 major Iranian cities, namely Tehran and Shiraz. This somewhat limits the generalizability of these findings to non-surveyed areas of Iran.

- It is unclear who volunteered to participate in this survey and who did not. Moreover, the reasons for opting to participate or not participate remain unknown. These are noteworthy because there may be systematic reasons behind who and why participants chose to participate or not that could be related to the outcomes of interest. This means generalizability of results from this survey are unknown.

- Interviews were restricted to bilingual (English and Farsi) members in Iran, who were better educated than many other Iranians. As such, the views of non-English-speaking members could potentially be different from those interviewed.

- These data come from a predominantly Islamic culture and generalizability of the findings to other national settings may be limited. It cannot be assumed that a level of adaptation of this magnitude would apply in non-Farsi Islam, or in countries with a predominantly Buddhist culture, or ones that generally disavow religion.

- This study was cross-sectional; measuring NA participation and substance use outcomes over time, at a minimum, are needed to determine whether NA participation is actually responsible for improved outcomes.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Key aspects of the NA 12-step culture and format appear transferrable to different cultural settings. This suggests that key mechanisms of behavior change that promote recovery in this fellowship (cohesiveness among members, ascription to the fellowship’s ideology, and the basic format of its group meetings), may be able to operate independent of the cultural setting where NA arose. For those in recovery, this means that attending NA meetings if/when traveling abroad may be able to meet your needs, despite differences in religion/culture of the host country or idiosyncratic practices of the group itself. Moreover, the group members may be similar to those you are familiar with in terms of demographics, with one key exception – gender. This will be important to consider if/when debating on attending an NA meeting while abroad, as different cultures have widely varying views on the role/place of men and women in the community.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Key aspects of the NA 12-step culture and format appear transferrable to ostensibly quite different cultural settings (e.g., a Muslim country such as Iran). This suggests that key mechanisms of behavior change that promote recovery in this fellowship (cohesiveness among members, ascription to the fellowship’s ideology, and the basic format of its group meetings), may be able to operate independent of the cultural setting where NA arose. This is important to note given the worldwide proliferation of NA meetings. Such diversity requires high level knowledge about mechanisms of action and effectiveness of adaptations of NA across cultures. As a result, providers may wish to invest time and resources in understanding these recovery support services in order to effectively refer individuals to groups that may meet their unique needs.

- For scientists: Key aspects of the NA 12-step culture and format appear transferrable to different cultural settings. This suggests that key mechanisms of behavior change that promote recovery in this fellowship (cohesiveness among members, ascription to the fellowship’s ideology, and the basic format of its group meetings), may be able to operate independent of the cultural setting where NA arose. However, there is very little NA-specific research overall, both in the U.S. and abroad. More work needs to be done to test NA’s ability to promote better substance use outcomes, and to isolate potential mechanisms of action and how this vary as a function of culture. Furthermore, community participatory research approaches that involve NA membership stakeholders (similar to, but not used here) may help advance our knowledge about NA and how NA works cross-culturally.

- For policy makers: Key aspects of the NA 12-step culture and format appear transferrable to different cultural settings. This suggests that key mechanisms of behavior change that promote recovery in this fellowship (cohesiveness among members, ascription to the fellowship’s ideology, and the basic format of its group meetings), may be able to operate independent of the cultural setting where NA arose. Despite this, there is still so much we do not know how NA works is the US or how other countries have adapted NA to meet their unique needs. As a result, increased funding for NA-specific research can help inform scientifically-grounded clinical and community practices.

CITATIONS

Galanter, M., White, W. L., & Hunter, B. D. (2019). Cross-cultural applicability of the 12-step model: A comparison of Narcotics Anonymous in the USA and Iran. Journal of Addiction Medicine, (ePub ahead of print). doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000526