Developing international consensus to address high-risk drug use and overdose

Among youth, there is high risk of mortality due to both substance use overdose and suicide. Addressing youth substance use and mental health can be challenging in clinical settings. Researchers in this study established an international consensus statement to guide the prevention, treatment, and management of high-risk substance use and overdose among youth.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Among youth, there is high risk of death due to both overdose and suicides. Despite fairly stable youth substance use rates, the US has seen a recent increase in youth overdose deaths especially during the COVID pandemic. These increases are possibly due to an increasingly contaminated drug supply, but could also be due to other factors. For example, youth mental health has suffered during this time, leading to increased risk of depression and anxiety, and an increased risk of substance use to cope with these feelings.

Addressing youth substance use and mental health can be challenging in clinical settings: youth are in a developmental phase where they may not be comfortable discussing these issues with parents present, but parents are also oftentimes responsible for ensuring their child receives adequate services and treatment. Clinicians are also pressed for time during a typical clinical encounter with an adolescent and may not be able to conduct an extensive history that would uncover underlying substance use behaviors or mental health challenges. As well, there are several challenges with getting youth access to treatment as well as with providing them with certain types of medication treatments used with adults (e.g., medication for alcohol or opioid use disorder).

As a result of the growing burden of preventable youth deaths and an understanding of the complex interplay of individual- and system-level challenges, the researchers in this study used a systematic, iterative process to establish an international expert consensus statement focused on the prevention, treatment, and management of high-risk substance use and overdose among youth who are ages 10 to 24 years old. The ultimate aim of this consensus statement is to be a first step in making system-level improvements to address this pressing issue.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The authors of this study used a method for building consensus known as the Delphi approach. They invited 31 experts worldwide from 10 different countries to participate (referred to as “panelists”). They selected panelists that had made important contributions to addiction psychiatry and adolescent medicine and attempted to ensure international representation and disciplinary diversity.

Panelists were first provided with a semi-structured questionnaire with 5 domains related to the issue of adolescent high-risk substance use: (1) clinical risks, (2) target populations, (3) intervention goals, (4) intervention strategies, and (5) settings/expertise. For the purposes of this study, high-risk substance use was defined as any use of substances with a high-risk of adverse outcomes and included misuse of prescription drugs, use of illicit drugs, and use of injection drugs. In this study, these substances, for example, included opioids and stimulants but not alcohol and cannabis.

The panelists’ responses to this questionnaire were used by the authors to develop an initial set of items for the consensus statement. The authors engaged in an iterative process of developing the statements, whereby they sent the panelists updated statements for rating. They were asked to rate all statements on a scale of 1–5, where 1 indicated they strongly disagreed with the statement and 5 indicated they strongly agreed with the statement. If panelists disagreed with any of the provided statements, they were asked to provide comments on its content and/or phrasing. Panelists could also propose new statements. Following this exercise, the authors updated the list with panelist feedback. This process was repeated twice and after the second round, any statements where there remained disagreement between panelists were discussed in a webinar with 15 of the expert participants. This process resulted in a finalized list of items for the consensus statement. Not all panelists participated in each round of the Delphi process.

The authors of this study had 31 expert panelists for their Delphi approach from 10 countries: 68% were psychiatrists, 13% were pediatricians, 10% were psychologists, 7% were general practitioners, and 3% were emergency medicine physicians.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

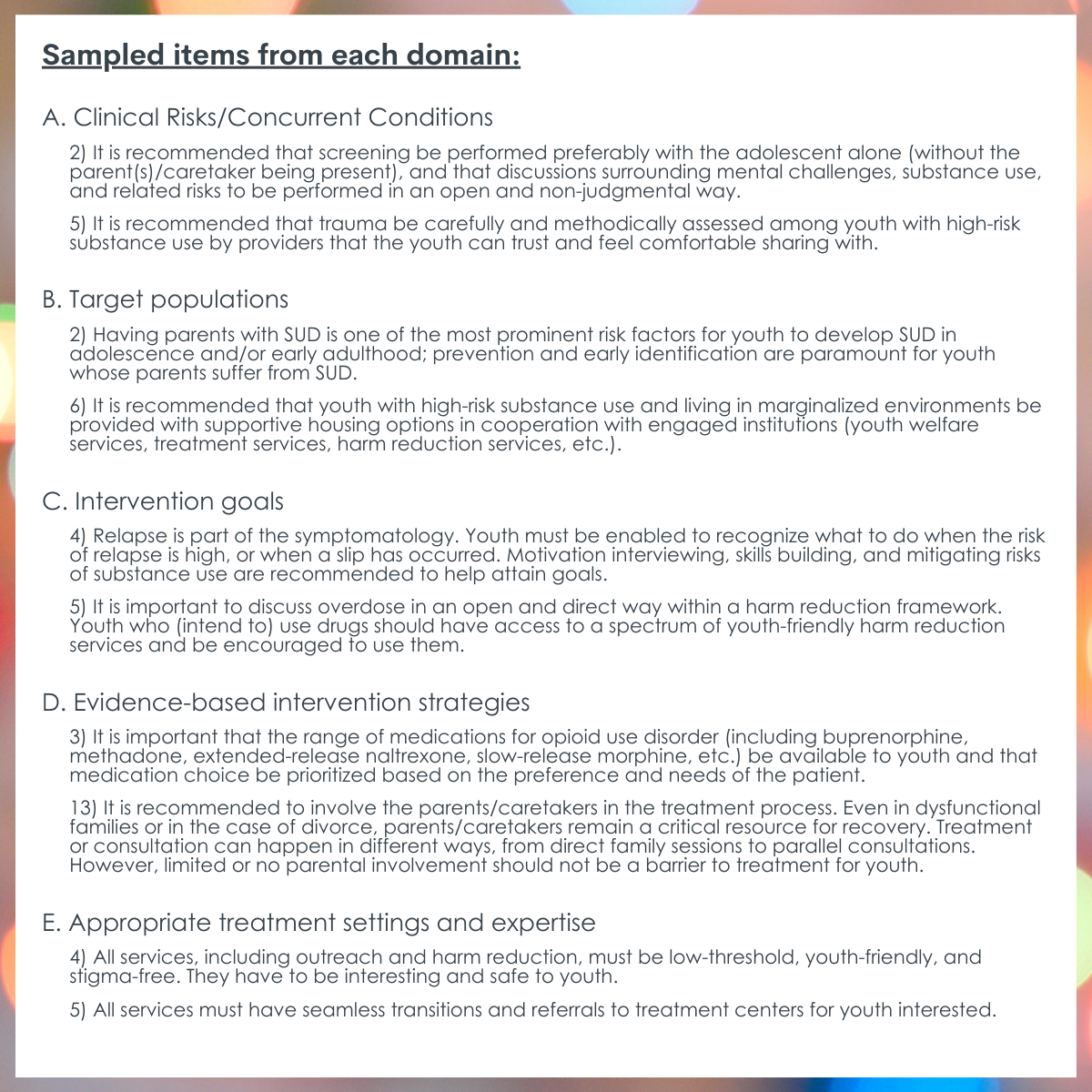

The Final International Consensus Statement included 60 individual statements.

The final consensus statement that was agreed upon by members of the expert panel was comprised of a list of 60 individual statements across the following domains: (1) clinical risks/clinical conditions, (2) target populations, (3) intervention goals, (4) evidence-based intervention strategies, and (5) appropriate treatment settings and expertise.

The consensus statement includes an item on relapse, indicating that this return to use is part of the symptomology of a substance use disorder. The panel encouraged efforts to identify and seek help for a “slip” when it happens. This suggests that the clinical consensus from this panel is one of addressing the nature of a substance use disorder as a chronic, relapsing condition among youth and using appropriate supports to address it. The authors also note that although abstinence is often the recommended clinical approach for youth, harm reduction approaches (e.g., providing naloxone) and engaging them in care should be major priorities as well.

The authors of the statement also noted some of its more ambitious goals. For example, although they agreed that screening youth is a necessary aspect of prevention and early intervention, they acknowledged that asking clinicians to expand their screening lists to address substance use and mental health might simply not be feasible in some settings. Similar to other assessments of the availability of comprehensive screening in healthcare, the authors suggest that the field might take advantage of online, and even automated, technology to assist not only with screening but also with early intervention.

Despite being able to agree on 60 items for the statement, and the authors’ attempts to resolve disagreements, the panelists could not agree on the issue of involuntary admission of youth.

The authors note this is a contentious issue and perhaps best understood along the entire treatment continuum where involuntary treatment is only used in cases of acute crises and oftentimes when the treatment system has already failed a youth. They suggest that while that issue is still up for debate, if the system is developed to have better communication with youth and their families and linkages to services, screening and early intervention remains the best way to avoid these acute crises and any need for involuntary admission.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

The authors of this study used a Delphi method with 31 experts in adolescent health, psychiatry, and psychology to develop an international consensus statement on the prevention, treatment, and management of high-risk substance use among youth ages 10-24 years. The final statement was comprised of 60 items across domains covering individual-level factors (clinical risks/clinical conditions, target populations) and setting level factors (intervention goals, evidence-based intervention strategies, appropriate treatment settings and expertise).

In developing the consensus statement, the authors acknowledged some system-level challenges that would need to be addressed to enact some of the statement’s items (e.g., clinical resources), as well as highlighted some contentious debates in the field. For example, the debate around adolescent autonomy in their healthcare, such as through involuntary admission to treatment for substance use or mental health issues is not a new one, so it is unsurprising that the panelists who were consulted were unable to agree on developing an item related to this issue.

Previous research has illustrated that the adolescent brain is still developing and that an adolescent has difficulty, and may not be capable of, thinking ahead to future consequences from his/her present-day actions. In addition, it is important to remember that chronic exposure to toxic and intoxicating substances can radically change neural circuits, negatively affect decision-making, and further increase impulsivity. Thus, to assume that drug exposed youth in the age-range targeted for this consensus statement (i.e., 10-24 years old) are “rational actors” may be a stretch. Indeed, some have argued, youth need “to be protected when they are unable to make their own decisions or where they cannot comprehend the implications of their decisions”. Given that we often assume that parents will act in their child’s best interests many argue that the parent should have a final say in issues where their child’s thinking may be compromised as a result of drug exposure. However, others would argue that allowing the adolescent to choose treatment without coercion is vital to maintain a developing adolescent’s right to autonomy, or right to make decisions about issues pertaining to their own body, despite the potential for adverse outcomes. As noted above, however, this might be moderated by the developmental level across this large maturational developmental age range that was of focus here (i.e.,10-24 years old). A pre-teen or young teen is very different from an 18-, 20-, or 24-year-old, differences that were not considered in this statement and are worth addressing. These opposing views are present in other healthcare domains aside from substance use and mental health (e.g., sexual behaviors), and thus constitute a critically important and ongoing debate for the field. Clearly, however, there is potentially more at stake here given the risk of premature death, disease, and disability, linked to substance use.

Finally, it was strange that the consensus statement omitted the inclusion of alcohol or cannabis as not constituting “high-risk” substance use, when many more youth die from alcohol-induced and -related events than all other drugs combined worldwide during this age range, and alcohol is the leading cause of disability-adjusted life years lost in this age-range, particularly in high-income countries like the United States. In fact, data from the World Health Organization (WHO) demonstrate that if an individual is going to become ill or die from something during the ages 10 and 24 years old it’s most likely going to be from alcohol. In addition, the dramatic increase in the potency of cannabis is resulting in increased incidence of psychosis among youth. Despite these substance-specific omissions in the creation of the statement, the consensus panel’s recommendations can apply equally well to young people’s use of these high-risk substances (alcohol, cannabis) as well.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The list of items for the consensus statement was developed with a broad audience of youth in mind. Additional statements developed with specific sub-populations of vulnerable youth in mind may help establish consensus for marginalized groups that healthcare inequities.

- The list was developed from an international group of experts, so there may be some country-specific adaptations necessary that address each nation’s unique health care system. It was also a relatively small sample for the broad (international) scope of the consensus statement, so the views presented may not be fully representative of all the experts in this area.

- The panel chose to omit alcohol or cannabis as constituting “high risk” substance use despite the fact that alcohol is the leading cause of death and disability between the ages of 10 and 24 years old, particularly in high income countries such as the United States according to data from the World Health Organization and cannabis is increasingly used by young people and has much higher potency that is leading to greater incidence of psychosis. This was an oversight but, nevertheless, these consensus statements can still apply to addressing these omitted substances.

BOTTOM LINE

In this Delphi study with 31 experts in adolescent health, psychiatry, and psychology, an international consensus statement was developed to address high-risk substance use among youth. Notably, although the experts could agree on 60 items relevant to youth across clinical risks/clinical conditions, target populations, intervention goals, evidence-based intervention strategies, and appropriate treatment settings and expertise, there remained several areas around both the developing adolescent’s autonomy and clinical infrastructure that may pose obstacles to system-level changes suggested by the consensus statement. Further research, collaboration, and consensus building will be necessary to achieve the ideals set out in the statement.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Early screening and intervention can be a crucial first step to stopping adolescent substance use experimentation from developing into a more severe problem. Adolescents who do use alcohol or other drugs may need several different types of supports to reduce their use or to stop using substances, especially if they are engaged in heavy use: this may also take several quit attempts. If you are concerned about your child’s substance use, you may be interested in talking to their primary care provider to address this issue in their clinical encounter. There are also available online government generated resources to identify adolescent-appropriate treatment options.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Conducting formalized screening for substance use and mental health should be an important part of the adolescent clinical encounter as addressing these behaviors and experiences is a first line defense against high-risk alcohol and other drug use and overdose. Youth may need a space separate from their parents or caregivers to be open about these behaviors. Having a nonjudgmental discussion with youth about their reason for using a substance may also help to identify other problems that could be addressed, for example, if they are using a substance to cope with negative feelings. The National Institute on Drug Abuse has several available screening tools that have been validated with youth, and there is an online government generated resource to identify adolescent-appropriate treatment options to suggest to youth and their families.

- For scientists: Rigorous research on adolescents’ experiences in clinical healthcare settings around screening, intervention, and treatment for high-risk substance use is necessary. This type of research is important for understanding where there are system-level gaps in early identification of alcohol and other drug use and for whom these gaps may be most likely. Research that addresses these issues may be able to provide strong support for the developed consensus statement and provide the necessary rationale for further developing infrastructure to close these gaps.

- For policy makers: This consensus statement lays out a variety of healthcare suggestions and issues to be addressed at the system-level to prevent and manage high-risk substance use among adolescents. Although written with/for an international audience, many of the statements pertain directly to the adolescent and clinician experience in the US healthcare system, particularly around developing adequate infrastructure for addressing alcohol and other use early and ensuring there are opportunities to engage youth in treatment and continuing care services.

CITATIONS

Krausz, M., Westenberg, J. N., Tsang, V., Suen, J., Ignaszewski, M. J., Mathew, N., . . . & Choi, F. (2022). Towards an International Consensus on the Prevention, Treatment, and Management of High-Risk Substance Use and Overdose among Youth. Medicina, 58(4), 539. doi: 10.3390/medicina58040539