Limiting the Life-impacting Consequences of Marijuana

The changing landscape of marijuana legalization & commercialization in many U.S. states has been widely publicized. Lessons can be learned from research on other legal drugs, like alcohol, particularly in terms of ways to limit consequences people might have from its use. This study investigated what kinds of factors place someone at risk for more marijuana consequences, and provided insight on how certain kinds of behaviors can help protect against them.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

The current national landscape for marijuana (more formally known as cannabis), including trends toward legalization and commercialization across the U.S. makes it even more important to study strategies to curb harmful use, and to limit consequences from that use. Addressing consequences for young adults is especially important as their still-developing brains can lead to lapses in judgment and decision making, compared to older adults, and they use marijuana more often, which can exacerbate these difficulties. Protective behavioral strategies are techniques individuals can use immediately before, during, or after use, intended to reduce the amount or frequency of use, as well as intoxication and resulting harm. Protective behavioral strategies have been studied extensively.

This study by Bravo, Prince, and Pearson focuses on the use of protective behavioral strategies related to marijuana use among college students, 25% of whom of have used marijuana in the past month. They tested whether potential risk factors for experiencing marijuana use consequences, including impulsivity-related personality traits as well as the reasons individuals used marijuana, related to how often they smoke, and to how many marijuana-related consequences they ultimately experience. Importantly, they also tested whether use of fewer marijuana protective behavioral strategies helps explain why these risk factors are related to worse marijuana outcomes.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The study used an online survey to assess 2129 students from psychology department pools at 11 universities who used cannabis (e.g., smoked marijuana) at least once in the previous month, from a possible 8141 total students. In the sample, 60% were White/Non-Hispanic and 18% Hispanic/Latino; 59% Female; and the average participant was 20 years old. Authors measured marijuana use frequency during the past week, asking students to report number of times they used marijuana, with options to choose up to ; (e.g., 8am-12pm, 12pm-4pm, 4pm-8pm, etc.), resulting in a maximum 42 times in the past week.

- MEASURES

-

- They used the Marijuana Consequences Questionnaire to ask participants whether or not they experienced up to 50 marijuana-related consequences (e.g., “I have said things while using marijuana that I later regretted” or “The quality of my work or schoolwork has suffered because of my marijuana use”).

- They measured protective behavioral strategies with a 39-item scale asking participants to report how often they used these strategies (e.g., “Avoid driving a car after using,” “Limit use to weekends,” and “Buy less marijuana at a time so you smoke less”).

- They measured impulsivity-related personality traits with a 59-item self-report measure that assessed:

- negative urgency (the tendency to act rashly when experiencing an unpleasant feeling)

- positive urgency (the tendency to act rashly when experiencing a pleasant feeling

- premeditation (the tendency to think about a plan or the consequences of a choice before making it; lower in impulsive individuals)

- perseverance (ability to remain focused on a task; lower in impulsive individuals)

- sensation seeking (tendency to engage in exciting, perhaps risky activities, and an openness to new experiences that may or may not be risky).

- They measured individuals’ reasons for using marijuana with the Marijuana Motives Questionnaire, a 25-item assessment which covers:

- coping (e.g., “to forget my worries”)

- expansion (e.g., “because it helps me be more creative and original”)

- conformity (e.g., “to fit in with the group I like”)

- enhancement (e.g., “to get high”)

- social (“because it makes social gatherings more fun”) reasons

The authors tested, all at once, whether expected risk factors for worse marijuana outcomes (e.g., coping motives) were related to more consequences, and whether that relationship was explained by the correlation between the risk factor and using protective behavioral strategies less often, which in turn, was related to more marijuana use.

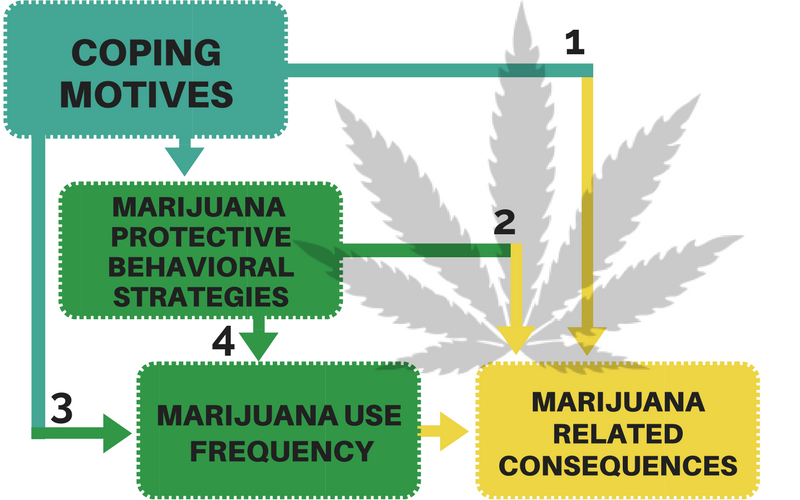

Although their model was somewhat complex, below we illustrate conceptually how authors used a predetermined (also referred to as “a priori” in scientific research) theory to help answer their research questions.

Path 2 represents that relationship but also looks specifically at whether it is explained by use of fewer protective behavioral strategies

Path 3 represents that relationship but also looks specifically at whether it is explained by more marijuana use

Path 4 represents that relationship but also looks specifically at whether it is explained by the connection between fewer protective behavioral strategies and more marijuana use.

- NOTE TO FIGURE ABOVE

-

It is important to note that while, theoretically, there is a time ordering to these four variables, they were all assessed at one time point – called a cross sectional study (“What were the limitations” contains further detail about this part of the study design).

One other statistical nuance worth pointing out is that authors used a significance level of .01 instead of .05 as is more typical. Without getting into too many “nuts and bolts” behind these numbers, this smaller significance level means that the relationships they were examining had to be larger to be considered reliable (i.e., not arrived at by chance). This is a conservative choice made because with larger samples (which was the case here at over 2000 individuals) very small relationships can be considered statistically reliable even though in day-to-day application, they may not be particularly meaningful. Lowering the significance level to .01 is a rigorous decision that attempts to protect against this possible scenario.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Overall, the study found that use of fewer protective behavioral strategies was related to more marijuana use and consequences.

For impulsivity-related personality traits, only negative urgency was related to consequences; however, this effect was not explained by how often individuals used protective behavioral strategies (e.g., using fewer strategies).

Regarding why people smoked marijuana, the relationships between both a) coping reasons, and b) expansion reasons, and marijuana consequences, adhered well to the theoretical model. Specifically, using marijuana to cope with difficulties and unpleasant feelings, and use of marijuana in an effort to be more original, creative, or to know oneself better, predicted use of fewer protective behavioral strategies, which then predicted more marijuana use, and ultimately more marijuana-related consequences. Relationships between using marijuana for conformity and enhancement reasons and marijuana use/consequences were less consistent, while, interestingly, using for social reasons was unrelated to these marijuana outcomes.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

Even though this study did not investigate marijuana treatment and recovery, per se, the findings here nevertheless have relevance for addiction recovery, particularly non-abstinent recovery. Protective behavioral strategies, like limiting use to weekends, may ultimately help reduce use and consequences, often the goals of non-abstinent recovery paradigms. More research is certainly needed to test whether this is true – that providing treatment to enhance use of protective behavioral strategies produces better non-abstinent marijuana outcomes over time. Studies are underway testing interventions to enhance use of protective behavioral strategies related to drinking, but not marijuana yet.

Also, results from a study of regular, young adult marijuana smokers in the Netherlands indicates that smoking marijuana to cope (coping motives) predicts greater likelihood of developing cannabis use disorder for the first time. In this way, it is reasonable to assume that protective behavioral strategies that directly reduce use of marijuana as a coping strategy would help improve likelihood of remission from cannabis use disorder as well. Again, though, more research is needed to investigate whether this is indeed the case.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The study was conducted only among college students taking psychology courses at 4-year universities, though spanning a wide range of universities, and using a large sample of individuals. Whether these research findings apply to other types of individuals cannot be determined from this study.

- As mentioned earlier, the study measured individuals at one point in time – it was a cross-sectional study. One strength of the study was a specific theory of how a risk factor would ultimately lead to more marijuana related consequences. That theory, though, inherently contains time ordering of the variables. For example, an individual is assumed to have difficulty coping with an area of their life (e.g., emotion regulation), then use marijuana to help with coping, which is related (either before, after, or during) to use of fewer protective behavioral strategies, which, in turn, relates to more marijuana use and ultimately more consequences. The cross sectional study design, however, did not allow for such a time-ordered analysis, and follow-up studies where researchers measure individuals at multiple points in time (e.g., longitudinal) are needed to better test the proposed theory of why some individuals develop more marijuana related consequences than others.

NEXT STEPS

Next steps might include using these findings as hypotheses about what will happen in longitudinal studies. Then, if longitudinal studies show similar results, interventions might be developed to help youth who smoke marijuana to enhance their use of protective behavioral strategies with the goal of reducing marijuana use and consequences.

This research could occur in clinical settings where abstinence may not be the treatment goal (sometimes called “harm reduction”) though may be less appropriate for abstinence-only treatment programs. Doing this kind of longitudinal study with different populations also (beyond college students) would help us understand how generalizable any such study findings might be.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Although this study focused on college students more generally, it is plausible that the findings may also apply to young people who are seeking non-abstinent recovery from marijuana, both in and outside treatment settings. Using marijuana to cope (e.g., “to forget about my problems” or “to cheer me up when I am in a bad mood) and to expand one’s experience (e.g., “to know myself better” or “to understand things differently”) might place someone at greater risk to have unpleasant consequences from their use. Importantly though, certain strategies might be able to help limit consequences, called “protective behavioral strategies”. These could include, for example: a) avoid marijuana use for several days in advance of an important day or task, b) only use at night (or on weekends), and c) avoid driving a car or after using or getting in a car with someone driving who has just used.

- For scientists: This article adds to a burgeoning literature on protective behavioral strategies for marijuana use, which in some ways is able to build on a similar literature for alcohol use. Its findings provide hypotheses about the helpful role of protective behavioral strategies, and the risks conferred by certain marijuana use motives (e.g., using to cope). These hypotheses should be tested in longitudinal research, and followed up by randomized trials to examine if interventions intended to increase use of protective behavioral strategies in at-risk marijuana smokers helps reduce consequences.

- For policy makers: Although this study focused on college students more generally, findings may also apply to young people who are seeking non-abstinent recovery from marijuana, both in and outside treatment settings. Using marijuana to cope (e.g., “to forget about my problems” or “to cheer me up when I am in a bad mood) and to expand one’s experience (e.g., “to know myself better” or “to understand things differently”) might place someone at greater risk to have unpleasant consequences from their use. Importantly though, certain strategies might be able to help limit consequences, called “protective behavioral strategies.” These could include, for example: a) avoid marijuana use for several days in advance of an important day or task, b) only use at night (or on weekends), and c) avoid driving a car or after using or getting in a car with someone driving who has just used. Given the changing landscape of marijuana legalization and commercialization across the U.S., much more research is needed to develop ways to limit consequences from marijuana use, particularly among youth. Policies to enhance financial and institutional support for this research might be helpful.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Although this study focused on college students more generally, findings may also apply to young people who are seeking treatment and have a goal to reduce their marijuana use and consequences, rather than quit completely. Using marijuana to cope (e.g., “to forget about my problems” or “to cheer me up when I am in a bad mood) and to expand one’s experience (e.g., “to know myself better” or “to understand things differently”) might place someone at greater risk to have unpleasant consequences from their use. Importantly though, certain strategies might be able to help limit consequences, called “protective behavioral strategies”. These could include, for example: a) avoid marijuana use for several days in advance of an important day or task, b) only use at night (or on weekends), and c) avoid driving a car after using or getting in a car with someone driving who has just used. More research is needed to determine if interventions can help people increase their use of marijuana-related protective behavioral strategies.

CITATIONS

Bravo, A. J., Prince, M. A., & Pearson, M. R. (2017). Can I use marijuana safely? An examination of distal antecedents, marijuana protective behavioral strategies, and marijuana outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 78(2), 203-212.