Different Pathways, Similar Approaches: Recovery from Cannabis Use Disorder

Marijuana is the 2nd most commonly used psychoactive substance (behind alcohol, not including nicotine) both nationally & internationally.

Within the United States, the social and political landscape surrounding use of different forms of cannabis (e.g., smoked marijuana, butane hash oil or “dabs”, and edible products) has changed considerably during just past couple of years, with medical marijuana and recreational legalization.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Greater access to cannabis may lead to increased rates of use (see here, for example), which could have implications for treatment and recovery from cannabis use disorder.

About 1 in 10 cannabis users, and 25 to 50% of those who use daily, will develop a moderate to severe cannabis use disorder.

There are several evidence based psychosocial treatments for cannabis use disorder (see here for a rigorous study that tested several treatments for adolescents). However, it is likely that, similar to several other substances, many individuals with cannabis use disorder will resolve their problems without formal treatment or mutual-help groups.

Also, like other substances, many will attempt to resolve their problems by cutting back rather than abstaining from cannabis entirely, at least initially.

There has been little research to date on the variety of ways in which individuals might recover from cannabis use disorders. Stea and colleagues addressed this research gap by surveying individuals with former, but not current, cannabis use disorder about their reasons for changing their cannabis use and actions they took to make the change and to maintain their moderation or abstinence goals.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Authors assessed and interviewed 119 adults via media advertisements in Calgary, Canada with a lifetime, but not past year cannabis use disorder – based on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview – meaning participants were in sustained remission. They compared the sample on several demographic and clinical variables, on whether they now moderate or completely abstain from cannabis, and whether they sought treatment/mutual-help or were non treatment-seeking (sometimes referred to as “natural” recovery) in order to help them make this change.

They also used qualitative analyses to examine whether participants’ reasons for changing their marijuana use, strategies to help them change their marijuana use, and strategies to help them maintain the change were different as a function of moderation/abstinence and treatment/natural recovery.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Of the 119 participants, 68 were abstainers and 51 were moderators, while 53 attended treatment and 66 did not attend treatment. Regarding demographics, the sample was 37 years old,on average, and made $43,000 per year, while 70% were male, 80% were Caucasian and, in terms of education, 85% had at least high school diploma. The only demographic difference reported was that abstainers were significantly more likely to be older than moderators.

NOTABLY FROM THE STUDY:

- Clinically, the sample scored 17 (out of a possible 38) on the Marijuana Problem Scale and endorsed 8 of 11 cannabis use disorder symptoms, on average, with abstainers and treatment seekers having significantly more problems and symptoms than moderators and non-treatment seekers, respectively

- Relative to non-treatment seekers, treatment seekers endorsed greater motivations to use marijuana when they were active users in order to enhance coping and to expand their experience (e.g., to become more creative)

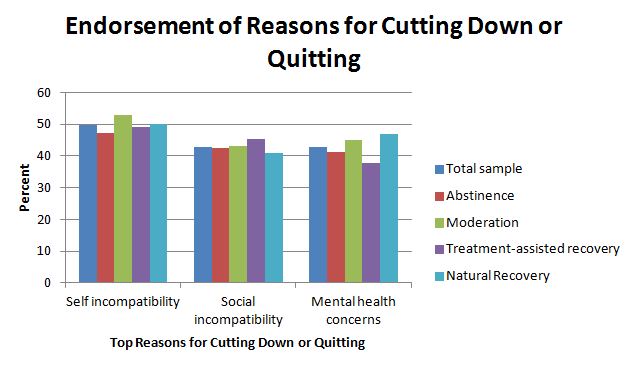

- Regarding reasons for change, the top three were:

- “self-incompatibility” (inconsistency with values and goals)

- social incompatibility (inconsistent with values of friends and family)

- mental health concerns (causing or making worse depression or anxiety)

There were no significant differences for abstainers and moderators or for treatment seekers and non treatment seekers for these multiple reasons, one of those, a less commonly endorsed reason, realization of harm (26%), was significantly more common among abstainers relative to moderators.

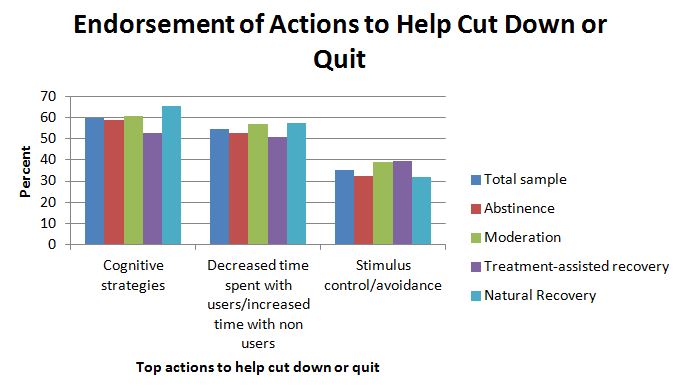

Regarding strategies to help participants cut down or quit, the top three were:

- cognitive strategies (i.e., thinking strategies such as weighing benefits and costs of use)

- decreased time spent with users and increased time with non users

- stimulus control/avoidance (i.e., decreased exposure to places and situations that used to be associated with cannabis use).

Finally, regarding strategies to help them maintain their change in marijuana use, individuals also used thinking strategies and changes in their social network, but also in the top three were hobbies and other distracting activities. This strategy was endorsed significantly more often among moderators compared to abstainers.

Regarding the identification of these reasons and strategies from participants’ open-ended written responses, there was a high degree of agreement between research staff who coded the participant responses, suggesting these responses were relatively clear and easy to identify.

Also important to note is that, relative to abstainers, moderators were significantly more likely to have close friends that used cannabis weekly or more (74% vs. 46%) and were less likely to perceive recreational cannabis use and medicinal cannabis use as harmful to society.

This study that used both quantitative and qualitative analyses (i.e., a mixed methods approach) was among the first to examine differences between individuals in remission from cannabis use disorder along both abstinence/moderation and treatment/non-treatment dimensions, simultaneously.

The findings provide knowledge on different pathways into cannabis use disorder remission and identify similarities and differences between these various forms of recovery. Like remission/recovery from alcohol use disorders, Stea et al.’s analyses suggest that, irrespective of the pathway and nature of one’s remission, individuals in recovery endorse using thinking strategies, changes in one’s social circle, and consciously avoiding risky places and situations to help them achieve this goal.

Also similar to individuals with alcohol and other substance use disorders, individuals with more severe problems are more likely to seek abstinence rather than moderation, and to seek formal help in their efforts to cut down or quit.

It is likely that cannabis use severity was associated with greater suffering which helped motivate individuals to avoid cannabis entirely (so as to avoid any risks of even a little use) or to seek formal help (due to failing to meet their goal on their own and thus increasing the likelihood of being able to successfully meet their cannabis goal).

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

While there is still much to learn about the short-term and long-term effects of cannabis, existing research suggests early, regular consumption may negatively impact brain development – particularly structures responsible for learning, memory, and inhibiting impulses (see here).

Cannabis or marijuana use has also been associated with:

- increased risk for mental health problems, with the strongest relationship found for psychotic disorders particularly among those with pre-existing genetic vulnerabilities

- may also be associated with a host of undesirable life circumstances including lower income, unemployment, and lower satisfaction with life

- impairment in driving ability with recent driving simulation studies showing performance declines with cannabis and alcohol separately, and declines even further when used together (see here)

- smoked marijuana may increase risk of cancer; however, because many marijuana smokers also smoke cigarettes, this effect is a complex one

In spite of these remaining questions particularly related to whether cannabis use causes these negative outcomes, these data suggest cutting back or quitting marijuana may have a number of health benefits.

For individuals with cannabis use disorder that are less motivated for change, this study suggests that identifying reasons that cannabis use might be incompatible with their goals and values, and also identifying the mental health consequences of use, might be helpful for evoking motivation to change.

For those that are motivated to change, it may help to work with them on thinking strategies (such as costs and benefits), on identifying ways to increase time spent with non users and decrease time spent with users (such as mutual-help groups and other settings where health is emphasized such as the gym), and on helping identify risky places and situations to avoid and ways to avoid them (i.e., through less risky hobbies and activities).

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The sample size was small and the study did not follow individuals over time but rather asked them to think back on their cannabis use and the different factors that contributed to using cannabis and changing their use.

- It is possible that participants’ current life situation influenced their perceptions of the past, and the results were not accurate representations of what actually happened.

- Although one unique aspect of the study was the use of interviews with another person to whom the participant was close and could verify their cannabis use and problem history (known as a “collateral” informant), the agreement between participants and collaterals were not reported in this study.

- Finally, the sample was 37 years old, on average, and was also mostly male, and Caucasian; the findings may not also apply to women, other ethnic groups, or younger cannabis users. This may be important as young adults (18 – 25) have higher rates of past month marijuana use than adults 26 and older (20% vs. 7%, respectively).

NEXT STEPS

Authors suggest that their findings may indicate an approach where individuals with less severe problems can be helped through less intensive methods like online self-management resources; those with more severe problems may benefit most from intervention, sometimes referred to as “stepped care” (see here for a discussion of this issue as related to alcohol). This is an issue that can be studied in future investigations.

In addition, longitudinal research shows that moderation may be a significantly riskier remission pathway than abstinence, with greater likelihood of relapse (see here). It is likely that this is also true for cannabis but requires further investigation.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: With cannabis use disorders, it may be helpful to know that Individuals who are able to get into remission use strategies such as the following: emphasizing the costs of cannabis in their mind, increasing non cannabis users and decreasing cannabis users in their social circle, and avoiding places and situations that place them at increased risk for marijuana use.

- For scientists: This preliminary study helped identify several hypotheses for future investigation including strategies that both treated and untreated individuals use to reduce or stop using cannabis, and reasons that individuals decide to change their cannabis use.

- For policy makers: Given the shifting social and political attitudes and behaviors related to cannabis use (e.g., reduced perception of harm and legalization/medicalization of cannabis), it is likely that more evidence-based treatment and recovery management options for cannabis use disorders will be needed; consider ongoing funding for such research.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: The sample of individuals in this study had been in remission from their cannabis use disorder for at least one year. Reported techniques that helped them achieve this included emphasizing the costs of cannabis in their mind, increasing non cannabis users and decreasing cannabis users in their social circle, and avoiding places and situations that place them at increased risk for cannabis use. These strategies may help your patients reduce or quit cannabis use.

CITATIONS

Stea, J. N., Yakovenko, I., & Hodgins, D. C. (2015). Recovery from cannabis use disorders: Abstinence versus moderation and treatment-assisted recovery versus natural recovery. Psychol Addict Behav, 29(3), 522-531. doi:10.1037/adb0000097