Killing Two Birds With One Stone: Telephone-based Continuing Care Saves Money & Improves Outcomes

Substance use disorders (SUDs) are widely recognized as chronic conditions, recently leading to an expansion of the conventional single-episode treatment model to a three-phased approach marked by:

(a) initial detoxification and/or symptom stabilization

(b) an acute, time-limited, more intensive treatment phase

(c) most critically, continuing care that facilitates maintenance and/or further improvements in health and functioning over time

Studies have shown they may be particularly effective when delivered over a longer period of time for higher-risk sub-groups.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

A recent review and meta-analysis (one integrative analysis of many individual studies) of continuing care interventions found that they are generally effective relative to minimal or no continuing care (see here).

Studies have shown they may be particularly effective when delivered over a longer period of time for higher-risk sub-groups. In order for continuing care interventions to be more readily adopted in clinical programs and reimbursed by health insurance companies, it is helpful to have evidence that continuing care is not only effective, but also cost-effective; that is, determining if the cost of providing the continuing care service is worth the recovery boost it provides.

In this study, McCollister, Yang, and McKay evaluated whether or not telephone monitoring and counseling, a continuing care intervention that has been tested in several prior studies, was cost-effective relative to treatment as usual.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

In this study, all patients had cocaine use disorder (i.e., cocaine dependence) and were admitted to an Intensive Outpatient Program that included 9 hours of group therapy each week, with a planned treatment course of 3 to 4 months. Consistent with the authors’ hypotheses, the original trial showed that adding telephone monitoring and counseling (TMC) to Treatment as Usual (TAU, which included weekly groups for 2 months after completion of the Intensive Outpatient Program) was effective particularly for more severe, high-risk patients defined as those who were using during admission to treatment and/or during the first 2 weeks of treatment. Adding financial incentives, $10 gift cards for each telephone session in which they participated telephone monitoring and counseling + giftcard (TMC+) did not yield any further benefit (see here).

telephone monitoring and counseling (TMC) included therapist phone calls that lasted about 20 minutes and focused on cognitive-behavioral coping skills (e.g., identifying and planning for high risk situations) and linkage to community support services such as 12-step mutual-help meetings. Calls began while patients were in the Intensive Outpatient Program and occurred weekly for 2 months, then once every two weeks for the remainder of the year, then once every month for the next 6 months, and once every 2 months for the final 6 months. The intervention was provided for 2 years.

Cost-effectiveness was calculated in two ways.

- First, the researchers calculated how much it cost to deliver the intervention on average per patient (e.g., staff salary, amount to rent building space, materials, patient financial incentives for the telephone monitoring and counseling + giftcard (TMC+ group, etc.). The cost-effectiveness for telephone monitoring and counseling (TMC), for example, was determined by subtracting the cost to deliver treatment as usual (TAU) from telephone monitoring and counseling (TMC) and dividing by the difference in abstinent days over the 2 year study period. This provided an estimate of how much more it costs to produce an extra day of abstinence, or incremental cost-effectiveness of the intervention.

- Second, in addition to the intervention cost, researchers also considered a) how much it cost patients to participate (e.g., travel time as some continuing care sessions were delivered face-to-face, lost opportunity to earn money at one’s job, child care), and b) cost/savings to society. They determined societal cost/savings with fairly complex monetary conversions that have been used in other studies, associated with four areas: 1) days with medical problems ($25.25 per day), 2) days with psychiatric problems ($10.22 per day), 3) days in jail ($60.35 per day), and 4) days of illegal activity ($998.41 per day).

For readers interested in how they determined the financial costs (and savings) for each of these activities, you can refer to this article (see here). How much each patient cost or saved society was calculated by subtracting the amount they cost during the 6 months before treatment subtracted from the amount they cost during the 2 years after receiving treatment. Then, they calculated the net benefit/cost of treatment, defined as intervention and patient costs minus the savings to society, for each extra day of abstinence produced. It is important to note that the mathematics do not work out perfectly because researchers used a procedure called “bootstrapping” to determine these average values, which means they performed the analyses many times, 1000 in this case, and took the average of those analyses.

All patients had lifetime cocaine use disorder and had used cocaine in the past 6 months. On average, patients were 43 years old and had 11 years of education (less than a high school degree); 76% were male, and 89% were African American. The three groups were similar on these demographic characteristics as well as clinical characteristics when they entered treatment, such as number of prior treatment episodes.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Out of a possible 720 abstinent days during the 2 year follow-up:

- telephone monitoring and counseling (TMC) patients had 609

- telephone monitoring and counseling + giftcard (TMC+) had 595

- treatment as usual (TAU) had 590.

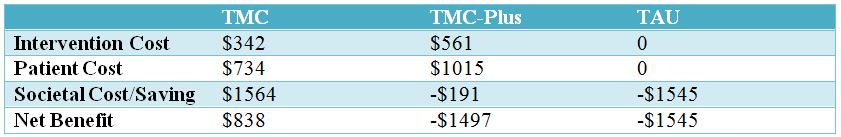

When considering just intervention costs, compared to treatment as usual (TAU), telephone monitoring and counseling (TMC) cost an additional $18.60 to produce an additional day of abstinence, while telephone monitoring and counseling + giftcard (TMC+) cost an additional $133 to produce an additional day of abstinence. Compared to TMC-plus, TMC patients had more abstinent days and cost less money to treat; thus a cost-effectiveness analysis was not needed because TMC was the clear winner.

When considering the net benefit, including intervention and patient costs, as well as societal cost/savings, telephone monitoring and counseling (TMC) was the clear winner relative to both telephone monitoring and counseling + giftcard (TMC+) and treatment as usual treatment as usual (TAU) because it produced more abstinent days and saved money for each patient treated, while TMC+and TAU cost money for each patient treated. It is worth mentioning that when authors looked just at the severe, high-risk individuals that benefitted from TMC in the original study, they were responsible for the savings in the TMC group. They also showed a substantial net benefit in the TMC+ group but were offset by costs of lower-risk patients.

For adults with cocaine use disorder that attend an intensive outpatient group substance use disorder (SUD) treatment program, adding telephone monitoring and counseling (TMC) is a cost-effective way to help strengthen treatment-as-usual. Also, providing patients with a relatively brief and low-maintenance continuing care service like TMC is not only likely to improve their chances of remission and enhanced quality of life, but also saves society about $1500 per person over the course of 2 years.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

Cost-effectiveness evaluations like the one in this study are important to help determine how much it costs to produce a positive outcome such as abstinence, and if that “investment” in treatment ultimately results in cost savings.

Information on cost-effectiveness can help make a case for the adoption of such interventions in clinical programs and treatment systems, and for insurance companies and government-subsidized health care to cover such services because ultimately covering them will save money while improving patient outcomes.

To this point, two large prior studies have yielded opposite findings for the cost-effectiveness of continuing care.

Among adults, recovery management check-ups have been shown to be cost-effective and cost-saving compared to monitoring only. Among adolescents, however, a continuing care intervention did not provide additional benefit over and above a combination motivational enhancement/cognitive behavioral treatment. One reason for this discrepancy may be that adolescents often have less severe substance use disorders (SUDs) than adults. Given that only the most severe patients in the initial trial benefited from telephone monitoring and counseling (TMC), and their savings to society drove the overall savings associated with providing TMC, it is possible that continuing care interventions may be most beneficial, and cost-effective for patients with severe SUDs (e.g., those who attend residential treatment or are on the severe end of the spectrum for outpatient programs).

Another interesting finding is that adding financial incentives was not cost-effective in this sample of cocaine dependent adults.

This stands in contrast to a prior Recovery Research Institute article review where adding incentives was a cost-effective addition to standard outpatient treatment for individuals with stimulant use disorders, a category that includes cocaine use disorders (see here). Although, in the continuing care study reviewed here where patients receiving incentives participated in significantly more telephone sessions, its inability to produce better outcomes (and thus limited its cost-effectiveness as well) may be explained by the greater importance of how much time someone remains in continuing care rather than how much treatment he/she receives.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- As the authors of the study point out, number of days in health care and criminal justice settings provide estimates of costs to society, but are not equal to the number of services in which the person participates or the number of crimes they commit. Using data like those instead of number of days would provide more accurate reflections of costs and savings to society. However, it is likely that more accurate estimates such as these would show greater cost-savings for telephone monitoring and counseling (TMC) relative to TAU rather than the reverse. Thus, the study’s findings still hold up in this case.

- Also, there was not a group of participants that received no treatment at all which studies have shown providing no treatment (e.g., wait list controls) produces worse outcomes. This may limit impact of this important study, but only in a minor way.

NEXT STEPS

Next steps may be to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of more contemporary mobile health continuing care approaches such as the Addiction Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (A-CHESS; see here for a brief review), and to compare their cost-effectiveness to telephone-based approaches like the one featured in this study.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Participating in continuing care interventions after treatment, including brief telephone calls that decrease in frequency over time with a clinician, is likely to increase chances of remission and recovery.

- For scientists: This important study showed that continuing care approaches like telephone monitoring and counseling are cost-effective, especially for individuals with more severe substance use disorders (SUDs). Strongly consider cost-effectiveness evaluations of interventions you may be developing or testing to help support their inclusion in treatment programs and systems and their coverage by health insurance companies and other third-party payers.

- For policy makers: Strongly consider implementing policies that make evidence-based continuing care interventions, like telephone monitoring and counseling, available in substance use disorder (SUD) programs that you oversee. It is not only likely to boost rates of recovery and remission relative to treatment as usual, but it is also likely to save you money. In other words, policies that help implement continuing care are likely to offer returns on your investment.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Strongly consider incorporating evidence-based continuing care interventions, like telephone monitoring and counseling, into treatment for your substance use disorder (SUD) patients, particularly those with more severe addictions. It is not only likely to boost their rates of recovery and remission relative to treatment as usual but will also result in overall health care savings.

CITATIONS

McCollister, K., Yang, X., & McKay, J. R. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a continuing care intervention for cocaine-dependent adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.032