Cannabis use disorder related to more severe and persistent alcohol use and PTSD symptoms in U.S. veterans

Rates of cannabis use disorder are on the rise among U.S. veterans, and existing research suggests that cannabis use is associated with more severe symptoms of mental health conditions that are also common in this population. This study examines the extent to which having a history of cannabis use disorder influences mental health and alcohol use over several years in a sample of U.S. veterans.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Cannabis use disorder (CUD) is one of the most prevalent substance use disorders in the U.S., with rates likely to persist and possibly increase nationally as medicinal and recreational cannabis is legalized in more places. Rates of CUD have been increasing among U.S. veteran populations, and some studies have found higher rates of cannabis use in veteran vs. non-veteran populations. Veterans also have higher rates of other co-occurring mental health difficulties (e.g., depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) compared with non-veterans. Some research suggests that veterans with CUD (compared to those without) are more likely to have co-occurring PTSD, as well as other substance use disorders, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders. Additionally, veterans with both CUD and PTSD exhibit more persistent PTSD symptoms than veterans who have PTSD without co-occurring CUD.

Much of the existing research on veterans has examined how psychiatric symptoms confer risk for developing CUD, rather than the other way around – the impact of CUD on the course of psychiatric symptoms over time. Additionally, less is known about the long-term mental health of veterans who have a diagnosis of CUD, as much of the existing research involves data collected at one time point or over a shorter period of follow-up. Some research on veterans using cannabis for medicinal vs. recreational purposes has found that veterans using cannabis medicinally report higher PTSD symptom severity as well as heavier cannabis use over time. There is also some evidence that veterans diagnosed with CUD exhibit more severe depressive symptoms over a year of follow-up.

More research examining a range of mental health symptoms within the same set of veterans over time (i.e., longitudinal research) for a prolonged period of follow-up can help determine if the presence of CUD has an impact on the duration and severity of co-occurring mental health conditions, and, if so, which conditions are most affected. Research in these areas can help inform intervention and prevention efforts to address cannabis use in this vulnerable population. In this study, researchers compared combat veterans’ mental health outcomes for those with CUD vs. those without CUD over a 7-year follow-up.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study used a sample comprised of 1,649 combat-deployed veterans who served in Iraq or Afghanistan between 2001 and 2009 and who agreed to be re-contacted by researchers over time. All participants completed a mental health evaluation at a Veterans Affairs (VA) clinic prior to study entry. Potential participants were identified through VA claims databases and selected at random. To ensure adequate representation, researchers attempted to recruit a greater number of veterans with PTSD and women (i.e., by oversampling). At study entry, medical records were used to determine if participants had a diagnostic history of CUD in the 10 years prior to study entry. Participants completed a set of assessments at study entry and four subsequent timepoints over the next 7 years. These assessments included measures of PTSD symptoms, depression and anxiety symptoms, psychosocial functioning, and alcohol use.

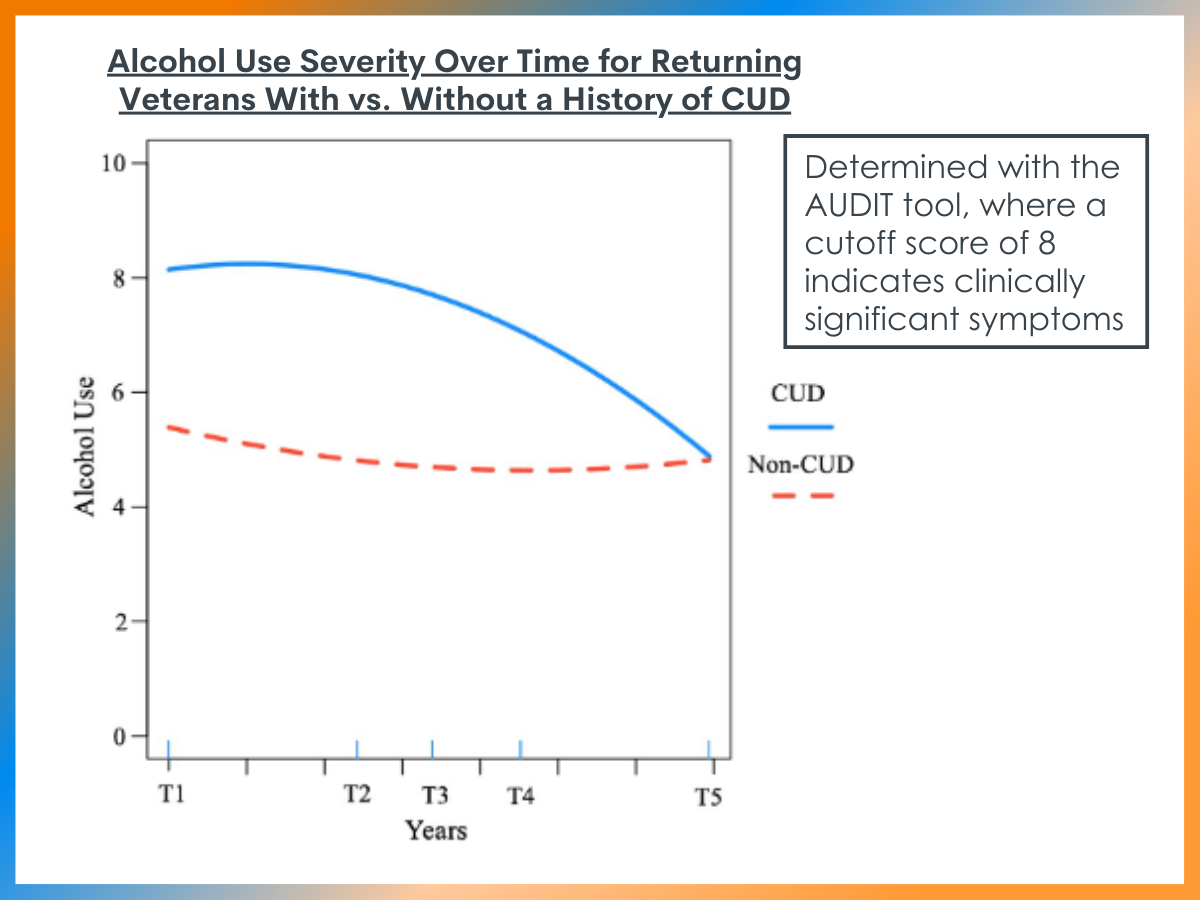

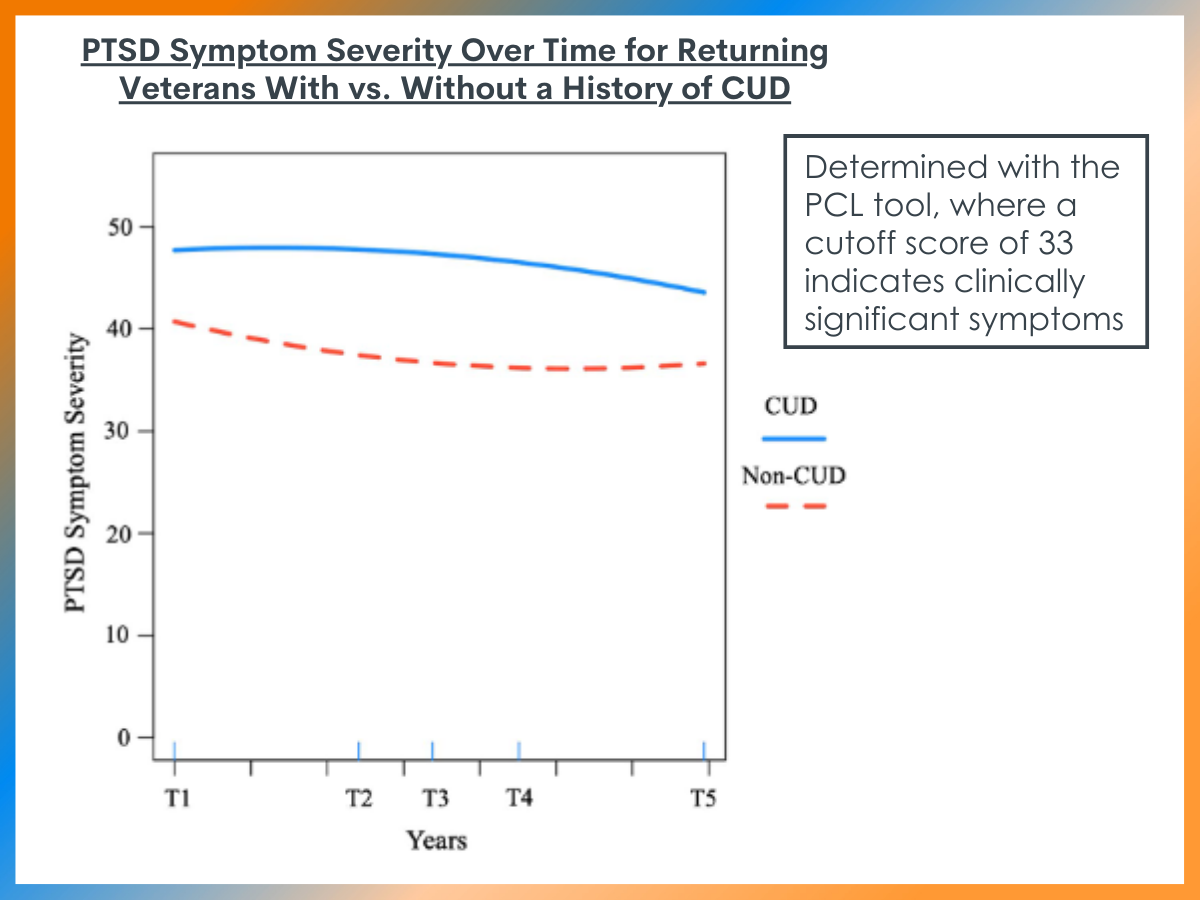

The researchers used an analytic strategy to characterize the course of these symptoms over time within individuals and to examine the degree to which history of CUD (present/absent) influenced symptoms at baseline as well as the course of symptoms over time. In addition to level of severity, the researchers were also interested in whether certain symptoms reached the clinical cut-off, specifically on measures of PTSD symptoms (clinical cut-off=33 for PTSD Checklist versions used) and alcohol use (clinical cut-off of 8 on AUDIT-C). The models also included demographic variables like gender, age, race, and time-since-deployment.

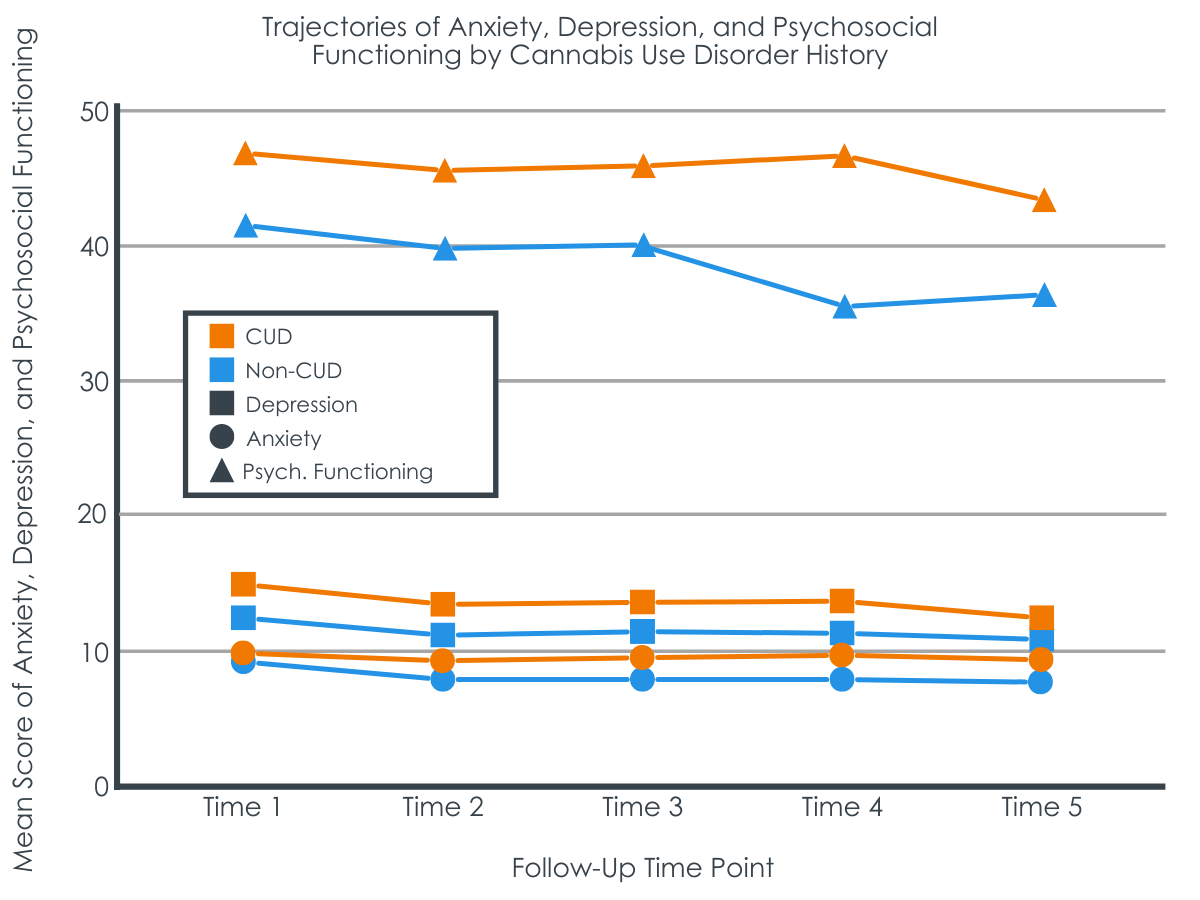

The final sample of 1,649 veterans included 115 participants with a history of CUD (60.9% Male, 67.8% White, average age 33.18 years) and 1,534 participants without history of CUD (49.2% male, 75.7% White, average age 37.81 years). On average, participants were around 73 months out from last deployment (73.69 months in CUD group vs. 73.73 months in non-CUD group). At study entry, participants from the CUD group reported higher levels of alcohol use represented by scores on the AUDIT-C (9.18 vs. 6.02), PTSD symptoms (50.13 vs. 42.01), depressive symptoms (15.85 vs. 12.65), and anxiety symptoms (9.98 vs. 9.13) and poorer psychosocial functioning (reflected in higher scores; 47.01 vs. 41.43).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

CUD history was associated with greater alcohol use severity at baseline and slower decrease in alcohol use over time.

Participants without CUD scored below the clinical cut-off for alcohol use disorder at baseline and showed a more immediate decrease in alcohol use, which stabilized over time. Participants with CUD started with scores above the clinical cut-off with slower decreases over time, not falling below the clinical cut-off until 4.5 years after study entry.

CUD history was associated with worse PTSD symptoms, depression, anxiety, and psychosocial functioning at baseline but predicted slower rate of improvement in PTSD symptoms only

Participants with CUD history prior to study entry reported more severe PTSD symptoms at baseline and demonstrated a slower rate of improvement over time when compared to participants without CUD history. Participants with CUD history reported more severe depressive and anxiety symptoms at baseline, as well as poorer psychosocial functioning. However, CUD history at baseline did not moderate the course of these symptoms, with the trajectories of these symptoms appearing similar in both CUD and non-CUD participants over time.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study adds to the emerging evidence that history of CUD can influence other co-occurring disorders, particularly in U.S. veteran populations. Specifically, this study found that veterans with a history of CUD reported more severe anxiety, depression, PTSD symptoms, and alcohol use as well as poorer psychosocial functioning at study entry. Additionally, baseline CUD history was associated with the longitudinal course of PTSD and alcohol use, specifically more severe symptoms and slower time-to-improvement over the 7 years of data collection.

The association between history of CUD and the trajectory of co-occurring mental health symptoms over time suggests several possible mechanisms that require further study to fully unpack. The researchers posit that there may be mutual maintenance between cannabis use and co-occurring symptoms (particularly PTSD); that is, psychiatric distress may contribute to individuals using cannabis (e.g., to help reduce or avoid difficult memories or feelings), which in turn may contribute to greater psychiatric distress over time and effectively maintain the relationship between substance use and psychiatric symptoms. Because the current study only examined the impact of baseline CUD on subsequent symptom trajectories, additional research examining both cannabis use and co-occurring symptoms at multiple points over time is needed to fully support this proposed model. Interestingly, researchers using data from four waves of the same dataset found that baseline risky alcohol use did not predict PTSD severity over time, suggesting there may be a unique risk conferred by CUD relative to alcohol use that likewise merits further investigation.

Although the reasons for cannabis use were not examined in the current study, there is emerging evidence to suggest that medicinal vs. recreational cannabis use may represent different pathways of risk.

For instance, several studies have found an association between medicinal cannabis use and psychiatric distress and impairment. In one recent study, researchers randomly assigned participants who were interested in obtaining a medical marijuana card to either receive a card immediately or after a 12-week delay. They found that participants who obtained a medical marijuana card for depression, anxiety, sleep, or pain were at increased risk of developing CUD (three times greater than those in the delayed condition) without relief from the symptoms they were seeking to treat (except for sleep).

Other research has found that recreational cannabis use is associated with increased alcohol use compared to medicinal use in a veteran sample. In the current study, researchers did not examine functions of use (i.e., medicinal vs. recreational) on subsequent outcomes. Examining the longitudinal effects of these different reasons for cannabis use (e.g., medicinal vs. recreational) on subsequent psychiatric symptoms and functioning will be an important focus for future research, particularly as legalization continues to spread.

There has been less research confirming anecdotal benefits of medicinal cannabis for PTSD and other mental health symptoms in this population outside of focus groups, and most of the existing research has been observational in nature. Thus, fully examining the potential effects—beneficial, neutral, or harmful—of cannabis on these symptoms in this population may require more rigorously designed studies, such as randomized controlled trials used to study other medications. Additional research is also needed to clarify the risks associated with regular cannabis use that does not meet criteria for CUD. Additionally, learning more about the predictors of developing CUD may also help inform prevention and treatment efforts.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- CUD status was based on chart review of medical records as opposed to actual structured interview conducted by the researchers. Although licensed professionals provided the diagnoses in patients’ charts, CUD may have been underdiagnosed in the sample.

- CUD status was defined as having a CUD diagnosis within the 10 years preceding study entry. It is unknown if CUD was active at the time of study entry. Additionally, details about the severity and duration of CUD are unknown.

- No information is available regarding whether participants used cannabis recreationally vs. medicinally. Also, no longitudinal information about cannabis use was collected over time, so it is unknown if changes in cannabis use over time correspond to changes in co-occurring mental health symptoms.

- It is unclear the degree to which the findings of this study generalize to non-veteran populations.

- Severity of CUD also was not specified in the study. Mild, moderate, and severe CUD levels may have very different relationships to psychosocial functioning and other psychiatric symptoms.

BOTTOM LINE

Veterans with a history of CUD at baseline exhibited more severe psychiatric symptoms (e.g., symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety) and more risky levels of harmful alcohol use as well as poorer psychosocial functioning when compared to veterans without a history of CUD. Additionally, history of CUD was associated with a worse and more protracted course (i.e., slower improvement) of alcohol use and PTSD symptoms over time. This study examined CUD at one timepoint (vs. use over time), limiting possible conclusions about the dynamic relationship of cannabis use and psychiatric distress over time. Thus, additional research is needed to clarify the clinical utility of using cannabis to treat distress related to PTSD, depression, and anxiety in veterans.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: A prior history of CUD is associated with more severe and persistent psychiatric symptoms and increased harmful alcohol use—in addition to any consequences associated with cannabis use itself. When cannabis is used to treat or cope with other mental health difficulties, it may not help improve these symptoms and may actually make these symptoms worse or cause them to persist longer. Thus, it is important to monitor cannabis use and seek support and treatment if you are concerned about a person’s current use, particularly if there are any co-occurring mental health concerns or significant alcohol use. Similarly, it may be important to seek treatment and support for other mental health concerns instead of turning to cannabis alone as a treatment for these difficulties.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study highlights how veterans with a history of CUD are at elevated risk for more severe and persistent co-occurring psychiatric symptoms (particularly PTSD) and risky alcohol use when compared to those without a history of CUD. These findings highlight the need to fully assess patients for extent of and reasons for cannabis use, particularly if they are presenting with PTSD, harmful alcohol use, or other mental health complaints, as CUD may represent a negative prognostic indicator for these patients. Conversely, it is important to assess for any co-occurring mental health difficulties and risky alcohol use patterns among patients presenting with current CUD, as these difficulties may perpetuate ongoing challenges with each of these types of challenges.

- For scientists: This study highlights how history of CUD is associated with elevated risk for more persistent and severe psychiatric symptoms in a sample of U.S. veterans who were followed longitudinally. Work in non-veteran samples is also indicated to ensure these results generalize to civilian populations. Additionally, this study only examined the effects of baseline CUD history. More research is needed to elucidate the time-varying effects of cannabis use on mental health over time. Additional research is likewise needed to determine if different reasons for cannabis use (e.g., medicinal vs. recreational) confer different types of risk over time or if there are other variables (e.g., sociodemographic variables, personal history, etc.) that moderate the relationship between cannabis use and mental health outcomes. That being said, it is possible cannabis may be helpful for some individuals, and existing research has generally relied on observational methods. More rigorous trials of the use of cannabis in treatment for mental health conditions (e.g., randomized controlled trials) will be needed to better understand these effects and guide policy and practice accordingly.

- For policy makers: A prior history of cannabis use disorder was associated with poorer mental health outcomes over several years of follow-up in this study. Given that the legalization of cannabis is expanding, it will likewise be important to expand intervention, prevention, and education efforts to curb problematic use and for parameters for medicinal use to be evidence-based. These findings also add to prior research demonstrating a fairly strong relationship between substance use disorders and other mental health difficulties, highlighting the importance of routine screening and assessment for both types of disorders when one or the other is a presenting problem, and how accessible, evidence-based treatments for these difficulties may be important for to improve outcomes for patients suffering from both types of challenges.

CITATIONS

Livingston, N. A., Farmer, S. L., Mahoney, C. T., Marx, B. P., & Keane, T. M. (2022). Longitudinal course of mental health symptoms among veterans with and without cannabis use disorder. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 36(2), 131–143. doi: 10.1037/adb0000736