What types of cannabis histories may lead to problematic adult outcomes?

As policies on cannabis become more liberalized across the United States and internationally, we may begin to see an increase in the number of people who consume this commonly used drug. Studies that outline how cannabis use over the life-course relates to adult outcomes can help inform public health recommendations and policies that follow legalization of recreational use. In this study, authors examined six different cannabis use patterns, associated long-term consequences, and childhood factors that predicted these patterns.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

It has become increasingly important to better understand the lifetime patterns of cannabis use and the long-term impact of these patterns, particularly as more states move toward cannabis legalization and people have easier access. Although cannabis is the most widely used substance other than alcohol in the United States, most people that use cannabis will not become regular users. In fact, it is estimated that roughly 10% of all cannabis users will go on to develop a cannabis use disorder. In addition, people that have resolved problems with cannabis tend to begin regularly using the drug at a young age (17 years old on average). This study examined different patterns of cannabis use over time from adolescence into adulthood, how these trajectories predicted a wide range of adult outcomes, and childhood factors associated with the classes involving persistent cannabis use. A better understanding of the types of people that persistently use cannabis into adulthood can inform public health policies as well as targeted prevention and intervention strategies.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

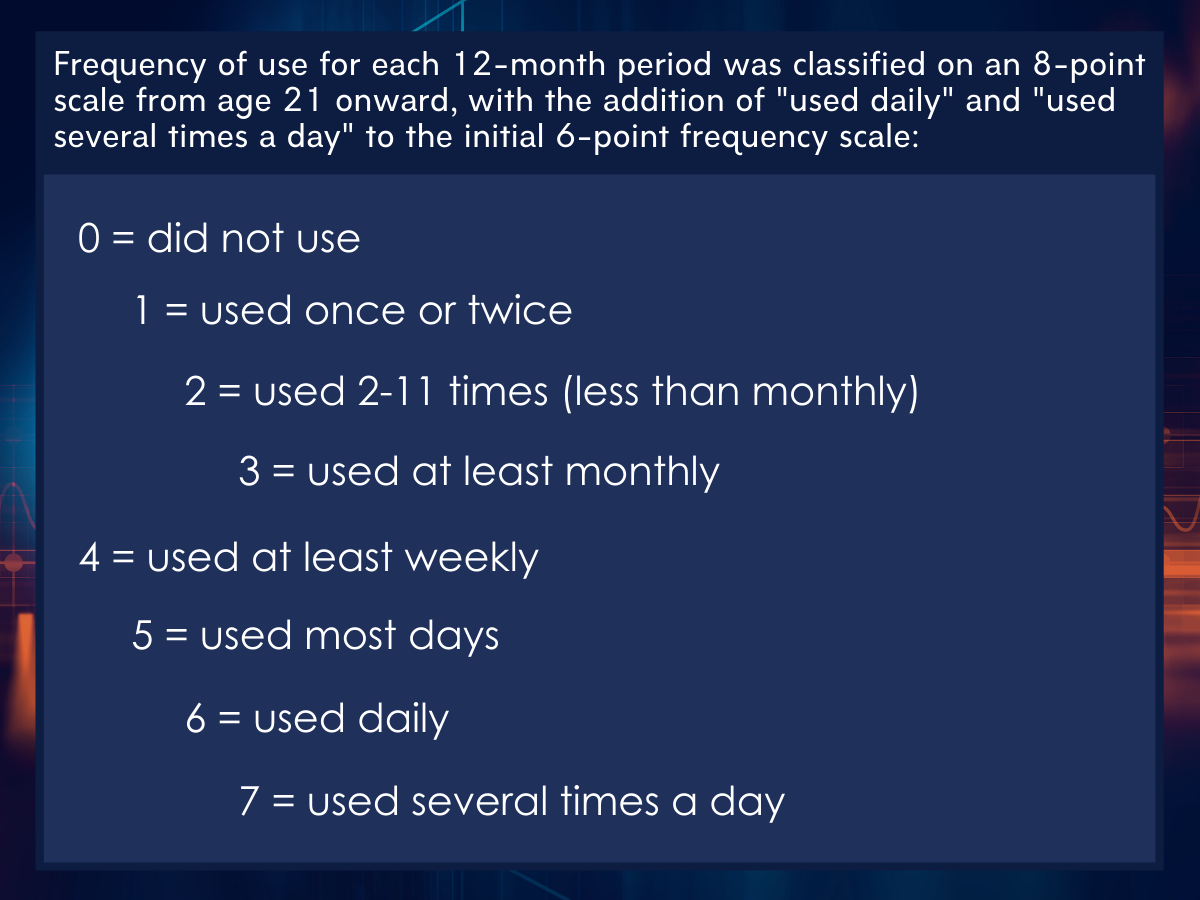

This study used a naturalistic, longitudinal design to compare 1065 individuals grouped together by patterns of cannabis use over time on adult mental health and functional outcomes. The study was conducted in Christchurch, New Zealand and used a study sample (n=1265) that consisted of a group of people from birth to adulthood (also known as a birth cohort). Study participants were categorized into different groups using a sophisticated statistical technique (called latent class analysis) based on their frequency of cannabis use from ages 15-35. Frequency of use was measured on a six-point scale before age 21 and an eight-point scale from age 21 onwards.

Figure 1.

Next, authors examined how these cannabis use groups related to various adult outcomes, such as the prevalence of both substance use disorders and mental health disorders (both measured by 4th edition of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, or DSM-IV) and socioeconomic, family, and social outcomes. That is, they examined whether these patterns of cannabis use were associated with different adult outcomes, after controlling for potentially confounding variables measured during childhood. This statistical control was done to try and isolate the effect of the type of cannabis use on adult outcomes which would increase their ability to make inferences that the lifetime patterns of cannabis use caused the adult outcomes. Adult outcomes were measured by interviewing study participants at age 35, where they were asked about their mental health and psychosocial wellbeing over the last five years. Authors also examined differences between the cannabis user groups on several childhood variables, to identify potential risk factors that might be addressed via prevention or intervention. These childhood variables included family socioeconomic and demographic background, behavioral factors (e.g., child conduct problems and novelty-seeking), family functioning, parental behavior, and trauma. Data from the birth cohort was collected from 1977 to 2012. Of the initial participants (n=1065), based on partial or complete data on cannabis use during the study period, over 90% completed the interview at age 35 (n=962).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

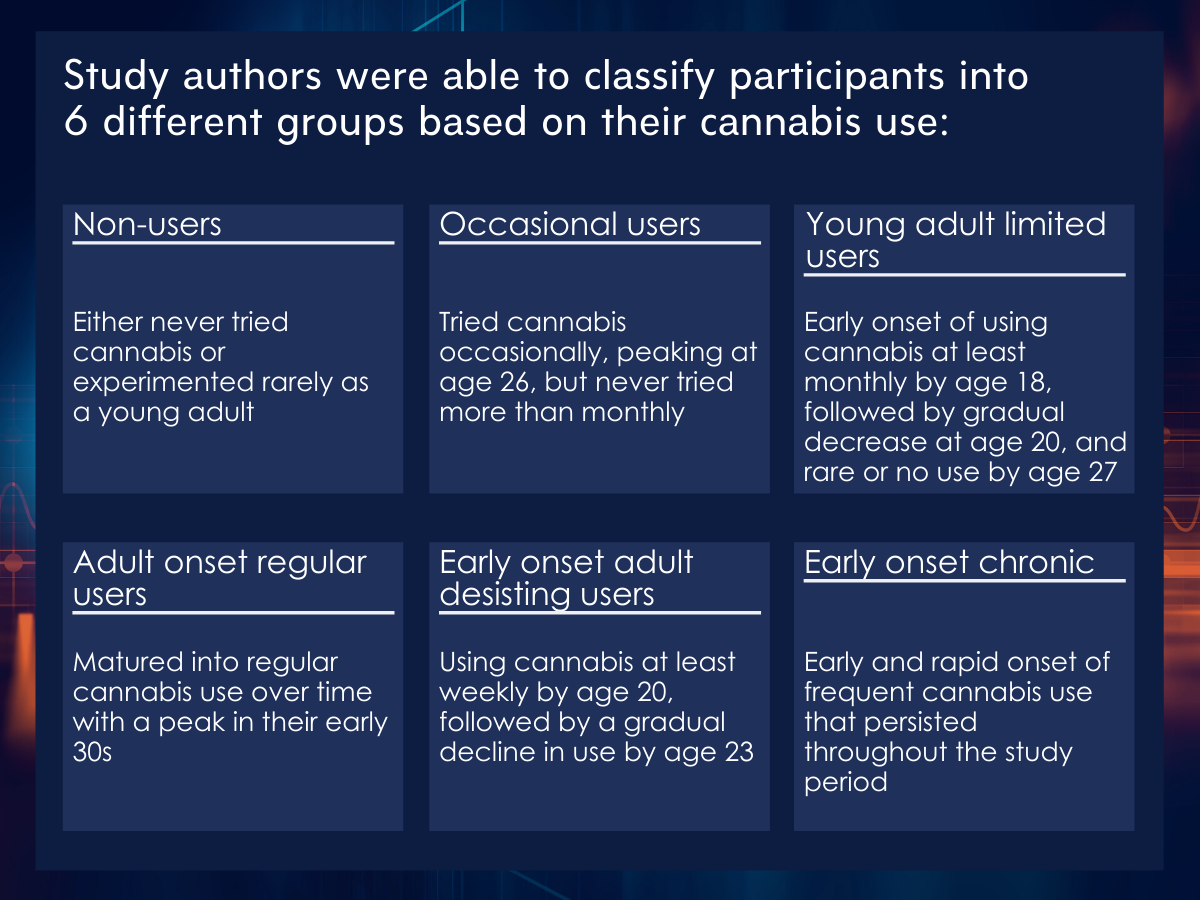

Authors identified six patterns of cannabis use over time.

Of all the participants in the sample, 663 were in the ‘Non-Users’ group, 110 were in the ‘Occasional Users’ group, 103 were in the ‘Young Adult Limited’ group, 56 were in the ‘Adult Onset Regular’ group, 82 were in the ‘Early Onset Adult Desisting’ group, and 51 were in the ‘Early Onset Chronic’ group.

Figure 2.

The authors considered ‘Adult Onset Regular Users’, ‘Early Onset Adult Desisting Users’, and ‘Early Onset Chronic Users’ as trajectories involving persistent cannabis use when assessing adverse adult outcomes and childhood predictors.

Groups characterized by persistent cannabis use were associated with adverse adult outcomes.

In general, those in the persistent cannabis use groups (‘Adult Onset Regular Users’, ‘Early Onset Adult Desisting Users’, and ‘Early Onset Chronic Users’) had the poorest adult outcomes and those in the ‘Non-User’ group had the best outcomes. Also notable was that those in the low frequency cannabis use groups (‘Occasional Users’ and ‘Young Adult Limited Users’) had outcomes that were similar to the ‘Non-User’ group. In particular, compared with the ‘Non-User’ group, those in the persistent cannabis use groups had substantially increased odds of illicit drug, alcohol, and nicotine dependence, moderately increased odds of mental health problems, had lower levels of socioeconomic status, and had a lower likelihood of having dependent children or being in a relationship and higher likelihood of relationship violence or incarceration. For example, compared to the ‘Non-Users’, the ‘Adult Onset Regular Users’ had a 74 times greater odds, ‘Early Onset Adult Desisting Users’ had a 17 times greater odds, and ‘Early Onset Chronic Users’ had a 66 times greater odds of meeting diagnostic criteria for illicit drug dependence other than cannabis.

Groups characterized by persistent cannabis use were associated with higher levels of childhood disadvantage.

In general, trajectories involving persistent cannabis use had the most disadvantaged profile of childhood, family, and individual characteristics. In particular, variables that were predictive of the persistent cannabis use groups included: male sex, conduct disorder and novelty-seeking in mid-adolescence, deviant peer affiliations, experience of childhood sexual abuse, parental history of illicit drug use, and having a greater number of changes in parental figures.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study identified six groups of individuals based on differing reported use of cannabis between the ages of 15 and 35. Patterns involving persistent cannabis use in adulthood (‘Adult Onset Regular Users’, ‘Early Onset Adult Desisting Users’, and ‘Early Onset Chronic Users’) were associated with a more disadvantaged childhood profile and showed worse outcomes across a wide range of adult psychosocial measures.

Although several explanations, such as Problem Behavioral Theory and “deviant-proneness”, may account for the study findings of the association of disadvantaged childhood risk factors, persistent cannabis use, and negative long-term outcomes, the relationship between persistent cannabis use into adulthood and adverse adult outcomes remains after controlling for childhood risk factors. In other words, while cannabis use may be associated with several adverse experience and risk behaviors during childhood which make individuals vulnerable to later difficulties rather than the cannabis use itself, study authors controlled for many such factors suggesting that these adverse experiences and risk behaviors are not sufficient in fully explaining the poorer adult outcomes among those groups involving persistent cannabis use. Thus, it is likely that long-term frequent cannabis use, or transitioning to such use, is an independent risk factor for a wide range of adverse outcomes in adulthood. This finding is especially relevant in societies today as liberalized cannabis policy may lead to greater availability, lower costs, and more use of cannabis.

There are several explanations of how frequent cannabis use can serve as an independent risk factor for harmful outcomes in adulthood. Cannabis may act as a “gateway” to other substances as suggested by the increased risk of substance use disorders among persistent cannabis use groups. This gateway effect may act directly, sensitizing the brain of those who use cannabis to the positive effects of other drugs; or, indirectly, exposing people who use cannabis to people who are using other drugs, thus increasing the chances they would be offered these drugs. Another explanation is that heavy cannabis use itself may cause long-term psychosocial harms. It is also important to note that cannabis use could be operating differently in each high-risk group. For example, in ‘Early Onset Chronic Users’, cannabis use may lead to increased risk for anxiety or depression whereas ‘Adult Onset Regular Users’ may turn to cannabis use in response to life challenges, such as anxiety or depression. More research is needed to better understand the mechanism of impact for frequent cannabis use on long-term outcomes so that prevention and intervention strategies can be tailored that take different cannabis use contexts into account.

Another important finding in this study is that one group of persistent cannabis use (‘Adult Onset Regular Users’) matured into a pattern of regular use in their early 30s, while another group that used cannabis somewhat frequently at a young age (‘Young Adult Limited Users’) had adult psychosocial outcomes that were not much different from the ‘Non-User’ group. Taken together, these findings suggest that, for some, the harmful effects of cannabis use persist beyond adolescence, implying a need for policy interventions and prevention strategies throughout the life course.

Importantly, studies that find support for an individualized intervention effect after that fact (e.g., because certain groups respond better to the intervention than others) may not be replicated when researchers hypothesize and test these individualized intervention effects from the outset. Thus, while this study does suggest a potentially useful approach that broadens prevention and intervention strategies for cannabis use across the life course, such intervention approaches must be tested out empirically before widespread implementation to maximize its chances of being impactful and cost-effective.

Lastly, one other important factor is accounting for the increasing potency of cannabis since the mid 1990’s, which corresponds with the study period (1977-2012). Thus, ‘Early Onset Adult Desisting Users’ and ‘Early Onset Chronic Users’ may have initiated frequent use of a less potent form of cannabis compared with ‘Adult Onset Regular Users’. If heavy cannabis use itself is causing long-term psychosocial harms, these adverse effects will likely be magnified with increased high-potency cannabis exposure and exposure to enhanced cannabis technologies (e.g. edibles).

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The adult outcomes were measured by interviewing the individual at age 35, asking the study participant to recall aspects of their mental health and psychosocial wellbeing over the last five years. This introduces recall bias, which is when participants do not remember previous events or experiences accurately or omit details.

- The rate at which participants drop out of the study over time (i.e., attrition) can be problematic in a longitudinal study because those who drop out of the study may be very different from those that remain in the study, leading to bias of the results. Importantly, authors used a statistical approach to minimize this type of bias.

- The three groups identified as persistent cannabis users (‘Adult Onset Regular Users’, ‘Early Onset Adult Desisting Users’, and ‘Early Onset Chronic Users’) had small sample sizes. This made it difficult statistically for the authors to be able to detect differences between the groups (i.e., limited statistical power) for both the model that predicts adverse outcome in adulthood and the model that identifies associated risk factors. It is possible that there were other meaningful differences between the six groups that were not identified, even after combining the three groups that involved persistent cannabis use.

- Cannabis use is strongly influenced by a society’s culture. This study took place in New Zealand, so the findings may not generalize to other countries like the United States or Canada. Cannabis use is strongly influenced by a society’s culture. This study took place in New Zealand, so the findings may not generalize to other countries like the United States or Canada.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study identified six groups of individuals based on differing cannabis use, of which three groups involved persistent cannabis use. These three groups had poorer adult outcomes and more challenges during childhood including adverse childhood experiences. The group that used cannabis frequently at the beginning of the study period then greatly reduced use into adulthood had much better outcomes than the groups that persistently used cannabis into adulthood and similar outcomes to the non-user group. This suggests that, if an adolescent has already begun using cannabis, there is a substantial benefit to reducing or ceasing use in adulthood. Also, parental drug use and parental instability were two factors that predicted membership in a persistent cannabis user group, highlighting family factors that can influence risky behavior in youths.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study identified six groups of individuals based on differing cannabis use from age 15 to 35, of which three groups involved persistent cannabis use. These three groups had poorer adult outcomes and more challenges during childhood including adverse childhood experiences. Some individuals frequently used cannabis as youths but greatly reduced or ceased use in adulthood while other individuals had the onset of persistent cannabis use in adulthood, with the latter group showing worse long-term outcomes. As a clinician, it is important to intervene early in the progression of frequent cannabis use in adolescents and young adults. However, occasional cannabis users at young ages have the potential to become frequent cannabis users in adulthood, which is associated with a wide range of adverse psychosocial outcomes. A life course approach should be considered when addressing cannabis use patterns in individuals. Also, due to disadvantaged childhood factors being associated with persistent cannabis use, this highlights the potential for individualized care based on behavioral, personality, and family-related factors.

- For scientists: This study used latent class analysis in a New Zealand birth cohort which identified six groups of individuals that differed based on self-reported cannabis use from age 15 to 35. In general, more challenges during childhood including adverse childhood experiences predicted membership into one of the three groups involving persistent cannabis use and these groups also had poorer outcomes in adulthood. Interestingly, long-term frequent cannabis use, or transitioning to such use, was found to be an independent risk factor for a wide range of adverse psychosocial outcomes in adulthood after controlling for childhood factors. It is not clear whether frequent cannabis use led to the development of other substance use and mental health disorders or that frequent cannabis use directly caused psychosocial harms. Due to more liberal cannabis policies internationally, further exploration into the mechanism of this independent risk factor is warranted. Also, some individuals frequently used cannabis as youths but greatly reduced or ceased use in adulthood while other individuals had the onset of persistent cannabis use in adulthood, with the latter group showing worse long-term outcomes. This is an interesting finding, though the sample sizes of the high-risk groups are small and the generalizability of the findings are limited by the unique sociocultural circumstances in New Zealand. Although cohort studies can be an expensive endeavor, replicating this study using an existing established cohort in another country with a larger sample size could be promising given that future cannabis policies will likely lead to greater availability, lower costs, and more use of cannabis.

- For policy makers: This study identified six groups of individuals based on differing cannabis use from age 15 to 35, of which three groups involved persistent cannabis use. These three groups had poorer adult outcomes and more challenges during childhood including adverse childhood experiences. Also, some individuals frequently used cannabis as youths but greatly reduced or ceased use in adulthood while other individuals had the onset of persistent cannabis use in adulthood, with the latter group showing worse long-term outcomes. These findings suggest that policy responses to emerging adults that show signs of persistent cannabis use may be inadequate, and a life course approach into adulthood should be considered. Although a study finding in New Zealand could look much different in another country and concrete recommendations cannot be made, the possibility of problematic cannabis use starting in adulthood should be considered for policies addressing prevention and intervention strategies, beyond reducing availability by implementing age restrictions where cannabis is legal.

CITATIONS

Boden, J.M., Dhakal, B., Foulds, J.A., & Horwood, L.J. (2019). Life-course trajectories of cannabis use: A latent class analysis of a New Zealand birth cohort. Addiction, 115, 279-290. doi: 10.1111/add.14814