Can cannabis substitute for alcohol in people receiving treatment to reduce their drinking?

It is not uncommon for individuals who are seeking to reduce or stop drinking to consume cannabis as a substitute for alcohol. While consuming cannabis may theoretically help some people reduce their alcohol intake, some studies have shown it can actually lead to worse drinking outcomes. This study explored if cannabis use influences same-day alcohol use among heavy drinkers seeking to reduce or stop drinking.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

It is not uncommon for individuals who are seeking to reduce or stop drinking to consume cannabis as a substitute for alcohol. While cannabis may help some reduce their alcohol intake, some studies have shown it can lead to worse drinking outcomes. For instance, one study showed that individuals who used cannabis infrequently during alcohol use disorder (AUD) treatment had fewer days abstinent from alcohol in comparison to cannabis abstainers. Better understanding the close time-related relationship between cannabis and alcohol consumption among individuals seeking to reduce or stop drinking has important implications for our understanding of how cannabis may help, or hinder individuals’ attempts to modify their drinking behaviors.

The authors of this study explored the same-day effects of cannabis use on alcohol consumption and binge drinking before, during, and after an 8-week manualized alcohol use intervention in heavy-drinking individuals who also consume cannabis. Given some evidence suggests people are more likely to substitute alcohol with cannabis in states with less prohibitions on cannabis, this research is notable for being conducted in Colorado, where recreational cannabis has been legal since 2012.

In this study with a sample of treatment-engaged, heavy drinkers who also consume cannabis, the authors aimed to: (1) Test whether cannabis consumption (yes/no) on a given day is associated with the number of alcoholic drinks consumed, or binge-drinking likelihood on that day. (2) Test whether the relationship between day-level cannabis and alcohol consumption and binge drinking likelihood is affected by sex. (3) Test whether the relationship between day-level cannabis and alcohol consumption and binge drinking likelihood is affected by participants’ cannabis use frequency (i.e., infrequent versus frequent use).

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a secondary analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial with 182 individuals assigned to receive either 8 weeks of manualized mindfulness-based relapse prevention or relapse prevention treatment to explore the influence of cannabis use on same-day alcohol consumption.

Parent study inclusion criteria were: a) being aged 21–60 years; b) no more than 10 days since last alcoholic drink; c) interest in reducing drinking; and d) reporting drinking more than 14 drinks/week on average during the past 3 months.

Individuals were excluded if: a) they were experiencing alcohol withdrawal; b) taking medications to treat bipolar or psychotic disorders; c) endorsing current suicidality, d) met criteria for psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder or a current major depressive episode; e) had a positive urine drug test (for drugs besides alcohol or cannabis); f) reported using drugs other than alcohol or cannabis in the 30 days prior to beginning the study; or g) were pregnant.

Participants were assessed at study weeks 4 and 8 (i.e., during treatment) for alcohol and cannabis consumption during the past month using timeline follow-back, a widely used measure for retrospectively assessing substance use. An additional follow-up assessment took place at 3 months.

Only participants who endorsed cannabis consumption were included in the secondary analysis (96 in total). The authors controlled for effects of treatment group (i.e., mindfulness-based relapse prevention vs. relapse prevention), as well demographic effects to isolate the relationship between cannabis and alcohol use, as best they could.

The total number of drinks per day was used to quantify alcohol consumption (range= 0–29) and whether the participant engaged in a binge-drinking episode on that day (defined as four or more drinks for women and five or more drinks for men).

In addition, participants were coded as either frequent or infrequent consumers of cannabis. Twenty-eight individuals who used cannabis on 15 days per month or more, on average, were categorized as frequent consumers, while 68 individuals who consumed cannabis on 15 days per month or less, on average, were categorized as infrequent consumers.

Just over half of participants were male (60%), with a mean age of 46 years. Most individuals in the sample were white (95%), had at least a bachelor’s degree (73%), reported an annual income of at least $40,000 (72%) and were employed full-time (76%).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Participants drank less alcohol on days when they consumed cannabis.

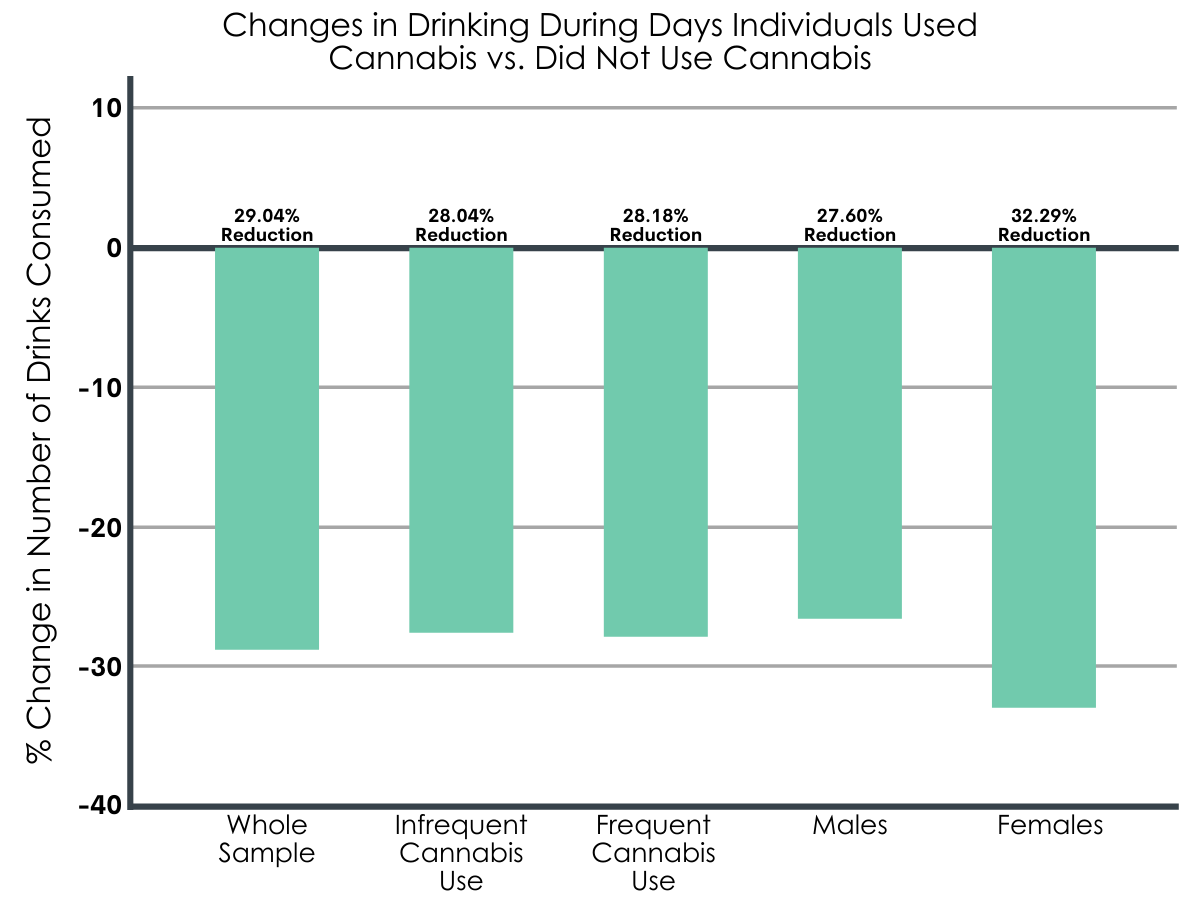

Individuals drank, on average, 29% fewer drinks on days when they consumed cannabis compared to days that cannabis was not consumed. Similarly, individuals were 2.1 times less likely to engage in a binge-drinking episode on days that cannabis was consumed compared to non-cannabis use days.

Women and men were not different in terms of the effect of cannabis use on alcohol consumption.

Women drank 32% and men drank 28% fewer drinks on days when cannabis was consumed compared to non-cannabis consumption days. However, this difference was not statistically significant. In other words, although there was an absolute between-sex difference of ~4%, statistically there was not a sufficient degree of confidence that this difference wasn’t simply due to chance.

Similarly, on days when cannabis was consumed, women were 2.9 and men were 1.8 times less likely to binge drink compared to non-cannabis consumption days. However, again, this absolute difference was not statistically significant.

Frequent and infrequent cannabis consumers were not different in terms of reducing drinking on days when cannabis was consumed.

Both individuals who consumed cannabis frequently and infrequently drank 28% fewer drinks on days when cannabis was consumed compared to non-cannabis use days.

In terms of effects of cannabis consumption on binge drinking, infrequent cannabis consumers were 2.3 times less likely to engage in a binge-drinking episode on cannabis consumption days compared to non-cannabis consumption days. However, for frequent cannabis consumers, there was no significant effect of cannabis consumption on binge-drinking episodes.

In addition, there was no significant difference between frequent and infrequent cannabis consumers in terms of odds of reporting a binge-drinking episode on days when cannabis was used versus days when it was not.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

The findings in this study are most notable for the fact that they suggest that cannabis consumption can help individuals who use cannabis with a goal of reducing or stopping drinking to reduce their alcohol consumption. Specifically, these findings showed that both frequent and infrequent cannabis consumers reduced their alcohol intake on days they consumed cannabis, and that infrequent cannabis consumers had less alcohol binges on days they consumed cannabis. The observed reductions in alcohol use are likely to be of benefit given any reductions in alcohol consumption can reduce long-term health risks (e.g., liver disease, cancers) and, given differences in the profile of consequences attributable to each specific substance, reductions in heavy alcohol use may lead to reductions in harms that have had more negative impact among those consuming both alcohol and cannabis.

While at face value this speaks to a benefit of cannabis for individuals seeking to reduce their drinking, the authors’ findings must be considered in light of several facts. Perhaps most importantly, the authors did not assess participants for cannabis use disorder or cannabis-related problems. Given participants classed as frequent consumers were consuming cannabis 85% of days the 3 months they were monitored in the study, it is possible many of these participants had cannabis use disorder. For such individuals, cannabis use would not be seen as protective, even though it may be associated with reduced alcohol consumption and potentially relative improvements in functioning.

It is plausible that many participants were substituting cannabis for alcohol. Though this may represent a reduction in net harm (these were individuals seeking to reduce their drinking, most likely because it was causing them problems), substituting cannabis for alcohol could have been an impediment to more effective behavior change strategies being learnt in treatment. Though the authors did not check this, it’s possible that participants who relied on cannabis to reduce their drinking may have had less adoption of the relapse prevention skills being taught in the parent randomized controlled trial. In other words, cannabis may have been used as a substitute to compensate for reduced alcohol intake as some of the pharmacological properties are common to both of these types of drugs (e.g., sedation, relaxation), but this could have been at the expense of acquisition of more effective behavior regulation strategies.

In addition, this study followed participants for a relatively short period of time (3 months; cut short because of COVID-19). It cannot be known how day-level cannabis consumption may have affected long-term drinking outcomes, nor is it known if cannabis use led to subsequent cannabis-related problems.

It is noteworthy that for frequent cannabis consumers, cannabis use was associated with reduced drinking, but not reduced binge drinking episodes. It is possible that this sub-group of participants were struggling more to regulate both their alcohol and cannabis consumption. Additionally, this analysis included only those who consumed cannabis. As such, any questions of cannabis substitution addressed in this study only apply to those with cannabis use experience and who are using fairly frequently.

- LIMITATIONS

-

As noted by the authors:

- It was not possible to determine the reasons for participants’ reductions in drinking on days when cannabis was consumed. In other words, though there was a correlation between cannabis and alcohol consumption, causation cannot be inferred from these data. It’s possible some other factor not measured was influencing these results.

- Heavy drinkers were not required to meet criteria for alcohol use disorder in order to participate in this study. These findings may not replicate with individuals with alcohol use disorder.

- Individuals in this study were recruited from the Denver and Boulder, Colorado region and were 95% White. It is unknown whether these results would generalize to other racial groups or groups from other areas or states where cannabis is not legalized and commercialize for recreational use.

Also:

- Cannabis use disorder was not assessed in this study. It is possible many of the frequent cannabis consumers in this study had cannabis use disorder. This is important to know because it influences the clinical and public health implications of these findings.

BOTTOM LINE

Among individuals who consume cannabis that were seeking to reduce or stop drinking and were engaged in relapse prevention treatment, cannabis consumption was associated with decreased same-day alcohol consumption regardless of sex and frequency of cannabis use. At the same time, it cannot be known from these data whether this resulted in a net benefit in functioning and well-being to participants. Future work is needed to determine how cannabis impacts alcohol consumption at later time-points post-treatment, as well as how the cannabis/alcohol use association may differ among different populations and among those diagnosed with alcohol use disorder and/or cannabis use disorder.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Cannabis consumption may help some individuals seeking to reduce or stop drinking to reduce their alcohol intake, however, it’s not clear from this study how cannabis consumption effects long-term drinking or how it helps or harms individuals with alcohol or cannabis use disorder. Using cannabis to manage a drinking problem confers risk for developing cannabis use disorder or their co-use may exacerbate other functional impairment. Safer, more effective strategies for reducing rather than quitting alcohol use, include Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and mutual-help programs like Moderation Management and Help Club. If alcohol abstinence is the goal then Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and mutual-help programs like Alcoholics Anonymous, SMART Recovery, Help Club, and The Phoenix may be helpful.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Cannabis consumption may help some individuals seeking to reduce or stop drinking to reduce their alcohol intake, however, it’s not clear from this study how cannabis consumption effects long-term drinking or how it helps or harms individuals with alcohol or cannabis use disorder. Given these gaps in the authors’ findings and because cannabis use also confers risk for developing cannabis use disorder, especially among individuals with a drinking problem, first-line treatments/approaches should be considered first, including Alcoholics Anonymous, SMART Recovery, or The Phoenix for those seeking alcohol abstinence, and Moderation Management, or Help Club for those seeking to reduce their drinking but not necessarily stop altogether. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy remains the first-line choice for helping individuals either moderate or stop drinking.

- For scientists: Cannabis consumption may help some individuals seeking to reduce or stop drinking to reduce their alcohol intake, however, it’s not clear from this study how cannabis consumption effects long-term drinking or how it helps or harms individuals with alcohol or cannabis use disorder. More research is needed to explore the long-term effects of day-level cannabis use on alcohol consumption. Additionally, this study did not test for potential effects of alcohol or cannabis use disorder on cannabis/alcohol use associations. Future studies exploring day-level relationships between cannabis and alcohol use should control for alcohol and cannabis use disorders, while also exploring how cannabis use may help or hinder uptake of relapse prevention skills. Research should also examine whether co-use of cannabis can reduce harmful alcohol use in a way that leads also to improved functioning. Given measures of functioning and well-being were not reported in this study, we do not know whether co-use while reducing alcohol use, may increase overall functional impairment.

- For policy makers: Cannabis consumption may help some individuals seeking to reduce or stop drinking to reduce their alcohol intake, however, it’s not clear from this study how cannabis consumption affects long-term drinking or how it helps or harms individuals with alcohol or cannabis use disorder. It is imperative that individuals have access to safe, evidence-based clinical care for alcohol and other drug use problems. Anything that can reduce barriers to treatment is likely to improve public health.

CITATIONS

Karoly, H. C., Ross, J. M., Prince, M. A., Zabelski, A. E., & Hutchison, K. E. (2021). Effects of cannabis use on alcohol consumption in a sample of treatment-engaged heavy drinkers in Colorado. Addiction, 116(9), 2529-2537. doi: 10.1111/add.15407