l

To address the opioid overdose crisis in the US, policymakers have enacted a variety of laws that target different drivers of the crisis or reduce associated harms. These include, as examples, laws on expanding Medicaid coverage of medication treatment for opioid use disorder, tracking opioid prescribing through Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs to intervene if an excess of prescriptions is detected, and increasing access to naloxone (commonly known by the brand name “Narcan”, a drug that reverses opioid-related overdoses). However, the impacts of these policies on actual rates of opioid overdose deaths are unclear, as is whether any potential impacts have changed over time or have differential impacts between racial groups.

Investigating the real-world impact of policies meant to prevent opioid overdose deaths can help policymakers understand if they are achieving the intended impact or if they may have unintended consequences. Researchers in this study examined whether enactment of opioid-related policies reduced risk of opioid overdose death, whether there were differences in their impact among ethnic and racial subgroups, and whether their impact varied over time. This research can help shed light on which types of policies are helpful for reducing opioid overdose deaths and which are unintentionally harmful, which can inform future policymaking efforts and save lives.

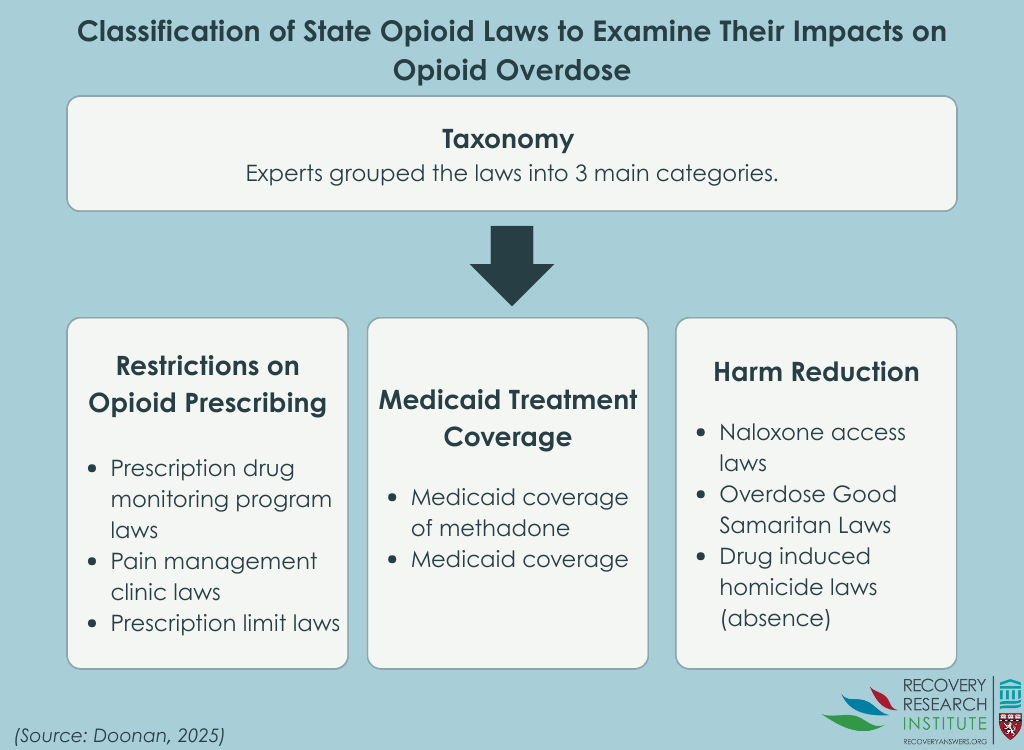

The researchers in this study examined whether enactment of state-level policies reduced the risk of opioid-related overdoses by developing a taxonomy and scoring system for a range of opioid-related laws. A panel of 56 experts were consulted to create consensus on the taxonomy, and they then scored the laws based on how helpful they perceived them to be. Panel members all had expertise in opioid-related policy and were from a variety of backgrounds, including academia, government, clinical practice, and advocacy.

Opioid-related laws from 50 US states and Washington D.C. were included. Data were obtained on the effective dates of 40 specific provisions of 8 types of laws for which longitudinal data were available. A variety of sources were used to obtain these data, including the Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System legal data repository, peer-reviewed literature, and reports. Laws were scored based on their enactment and varied from non-enactment (scored as 0) to full enactment (scored as 1).

The study team created the taxonomy (see Graphic below) by initially classifying 8 types of overdose laws and 50 provisions from these laws into 3 domains: opioid prescribing restrictions, “harm reduction”, and Medicaid treatment coverage. Then, they consulted the expert panel for feedback and consensus was achieved. The opioid prescribing restrictions domain included laws on prescription drug monitoring programs, pain clinics, and prescribing limits for acute pain. The “harm reduction” domain included laws on naloxone access, Good Samaritan, and the absence of drug-induced homicides. The Medicaid treatment coverage domain included laws on Medicaid methadone coverage and Medicaid expansion.

Next, 2 sets of scores for the provisions within each of these policy domains were created based on ratings of helpfulness from the expert panel. The panel rated each provision on a scale of 0-4, with 0 being very harmful and 4 being very helpful. The first set included “All Provisions,” where all expert-rated laws and provisions were included. The second set included the “Top 20 Provisions,” where the provisions that were rated most highly by the expert panel were included. These two sets were compared for their effectiveness in reducing risk for opioid-related overdoses, with the hypothesis that the Top 20 Provisions set would be just as strong a predictor of overdose than the All Provisions set, since they were rated to be among the most helpful at reducing overdose risk. Because findings were similar whether the study examined all provisions or just the top 20, we summarize only those from “All Provisions” (i.e., the entire set of policies).

Data for overdose deaths were obtained from the National Vital Statistics System, housed within the National Center for Health Statistics, using restricted-use files with information regarding detailed multiple cause of death mortality across all counties between 2013 and 2020. This system is based on national poisoning surveillance standards for opioid overdose. Information on race was also obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics mortality data and corresponding data on race within the greater population, which allowed the research team to compare effects between groups. Due to data availability, the 3 largest single race groups were included: non-Hispanic Black/African American people, Hispanic/Latino people of any race, and non-Hispanic White people.

Analyses controlled statistically for these variables at the county level: percent men; percent White/non-Hispanic population; percent Black/non-Hispanic population; percent Hispanic population; percent of the population ages 0–17, 18–24, 25–44, and 45–65; percent of families in poverty; percent of civilian labor force unemployed; and median household income. These data were obtained from the American Community Survey for the years 2012-2019. Additionally, researchers obtained data on the annual population density per 1,000 square miles, annual rates of death from all-cause mortality per 1,000 residents, and annual percentage of drugs positive for fentanyl within top 60 drugs seized by the Drug Enforcement Agency for each state to control for these variables as well. Such statistical adjustments help to isolate the effects of interest – i.e., whether enactment of opioid-related laws and provisions reduced risk of overdoses.

Analyses examined the associations between enactment of overdose-related provisions between 2012 – 2019 and the risk of opioid-related overdose deaths between 2013 and 2020 – the predictor and outcome were time-lagged meaning they examined the effects of opioid policy on overdose in the following year. The study also examined these associations among racial and ethnic subgroups from 1,485 counties. Analyses controlled for the covariates described above.

Naloxone (Narcan) distribution and other “harm reduction” policies decreased risk of overdose deaths, while opioid prescribing restriction policies and Medicaid treatment coverage policies initially increased risk

Overall, more opioid-related policies were enacted towards the later years of the study. The overall nationwide rate of opioid-involved deaths also almost tripled over the study period, from 8 deaths per 100,000 people in 2013 to 21 deaths per 100,000 people in 2020. Yet, the range varied substantially, from 0-1,755 deaths per county, with 29%-38% of counties having 0 deaths in any year (with fewer counties towards the end of the study period).

Between 2013 and 2020, enactment of laws from the “harm reduction” policy domain within a given year was associated with a 16% reduction in the risk of opioid-related overdose death in the subsequent year.

However, enactment of laws between 2013 and 2020 from the opioid prescribing restriction and Medicaid treatment coverage policy domains was associated with an increased risk of opioid-related overdose deaths. Specifically, enactment of laws from the opioid prescribing restriction domain was associated with a 24% increased risk of overdose death in the subsequent year. Enactment of laws from the Medicaid treatment coverage domain was associated with a 14% increased risk of overdose death in the subsequent year. Importantly, however, this differed over time. Between 2013 and 2016, enactment of laws from the opioid prescribing restriction domain and the Medicaid treatment coverage domain within a given year was associated with a 35% and 20% increased risk of opioid-related overdose death in the subsequent year, respectively. However, between 2017 and 2020, there were no associations between enactment of prescribing and Medicaid laws from these domains and risk of opioid overdose death.

Effects differed by race/ethnicity

For the racial and ethnic subgroup analyses, the protective effect found for naloxone availability and other harm reduction policies between 2013 and 2020 only remained for White individuals, while there was no association found for Black and Hispanic/Latino individuals. Likewise, the increase in risk found for the Medicaid treatment coverage policies only remained for White individuals and there was no association found for Black and Hispanic/Latino individuals. There were no differences for risk of opioid-related overdose death between racial and ethnic subgroups for opioid prescribing restriction policies.

The research team examined whether enactment of opioid-related policies reduced risk of opioid overdose death in counties nationwide, whether there were differences in their impact among ethnic and racial subgroups, and whether their impact varied over time.

Results showed that more naloxone availability and other policies focused on reduced consequences of opioid use decreased risk of opioid overdose death, while, somewhat surprisingly, opioid prescribing restriction policies and Medicaid treatment coverage policies increased risk. However, when examining their impact across time, the increase in overdose risk found for opioid prescribing restriction and Medicaid treatment coverage policies dissipated during the later years of study period to have no association – meaning there were no harms but no benefits either. The ethnic and racial subgroup analyses revealed that the decrease in risk from harm reduction policies and increase in risk from Medicaid treatment policies remained only for White individuals.

First, these findings add to other studies suggesting public health benefits from services that focus on reducing harmful consequences of drug use, including evidence that supervised consumption sites reduce rates of infectious disease and overdose deaths, harm reduction supply dispensing machines decrease the incidence of overdose deaths and HIV cases, and increased access to naloxone reduces opioid-related mortality.

The finding that the increase in overdose risk found for opioid prescribing restriction and Medicaid treatment coverage policies diminished to no effect during the later years of the study, while harm reduction policies maintained their beneficial effect across the entire study time period, suggests that these policies may have helped to alleviate some of the unintended consequences that resulted from opioid prescribing restriction and Medicaid treatment coverage policies earlier in the study. For instance, opioid restrictions may have resulted in more people (e.g., with chronic or severe pain) turning to synthetic opioids and heroin from an unregulated supply. Another possible explanation is that there may be a delay in the observed benefits from restricting opioid policies, with one study showing there may be up to a decade-long time lag between restrictions and prevention of opioid-related overdoses.

The finding that more Medicaid coverage was associated with initially increased overdose rates was also unexpected. It is possible that more Medicaid coverage for methadone increased overdose risk, as methadone—a full opioid agonist—has this potential. It is also possible that states expanded Medicaid coverage in response to worse overdose rates – for example, if states with more progressive drug laws have more urban areas and also were more likely to expand Medicaid, that could account for unexpectedly higher overdose rates. Notably, the analyses adjusted for many variables to try and account for this type of “selection bias”, but such approaches cannot account entirely for this possibility.

The results from the ethnic and racial subgroup analyses showing that the decrease in risk from harm reduction policies and increase in risk from Medicaid treatment policies remained only for White individuals suggests that there are potentially greater benefits and harms stemming from opioid-related policies for White individuals. This may be due to the epidemiological trends showing that the opioid overdose epidemic initially affected White people more than other ethnic and racial groups. However, greater investigation is needed into whether harm reduction policies benefit White people more to ensure equitable design and implementation of these policies, so that the maximum number of people benefit from these life-impacting opioid-related policies.

Naloxone (Narcan) availability and other policies to decrease opioid use consequences decreased risk of opioid overdose death, while opioid prescribing restriction policies and Medicaid treatment coverage policies unexpectedly increased risk. However, the increases for opioid prescribing restriction and Medicaid treatment coverage policies dissipated during the later years of study. The decrease in risk from harm reducing policies and increase in risk from Medicaid treatment policies remained only for White individuals, reflecting the potential for both greater benefits and harms for White people.

Doonan, S. M., Wheeler-Martin, K., Davis, C., Mauro, C., Bruzelius, E., Crystal, S., Mannes, Z., Gutkind, S., Keyes, K. M., Rudolph, K. E., Samples, H., Henry, S. G., Hasin, D. S., Martins, S. S., & Cerdá, M. (2025). How do restrictions on opioid prescribing, harm reduction, and treatment coverage policies relate to opioid overdose deaths in the United States in 2013–2020? An application of a new state opioid policy scale. International Journal of Drug Policy, 137. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2025.104713.

l

To address the opioid overdose crisis in the US, policymakers have enacted a variety of laws that target different drivers of the crisis or reduce associated harms. These include, as examples, laws on expanding Medicaid coverage of medication treatment for opioid use disorder, tracking opioid prescribing through Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs to intervene if an excess of prescriptions is detected, and increasing access to naloxone (commonly known by the brand name “Narcan”, a drug that reverses opioid-related overdoses). However, the impacts of these policies on actual rates of opioid overdose deaths are unclear, as is whether any potential impacts have changed over time or have differential impacts between racial groups.

Investigating the real-world impact of policies meant to prevent opioid overdose deaths can help policymakers understand if they are achieving the intended impact or if they may have unintended consequences. Researchers in this study examined whether enactment of opioid-related policies reduced risk of opioid overdose death, whether there were differences in their impact among ethnic and racial subgroups, and whether their impact varied over time. This research can help shed light on which types of policies are helpful for reducing opioid overdose deaths and which are unintentionally harmful, which can inform future policymaking efforts and save lives.

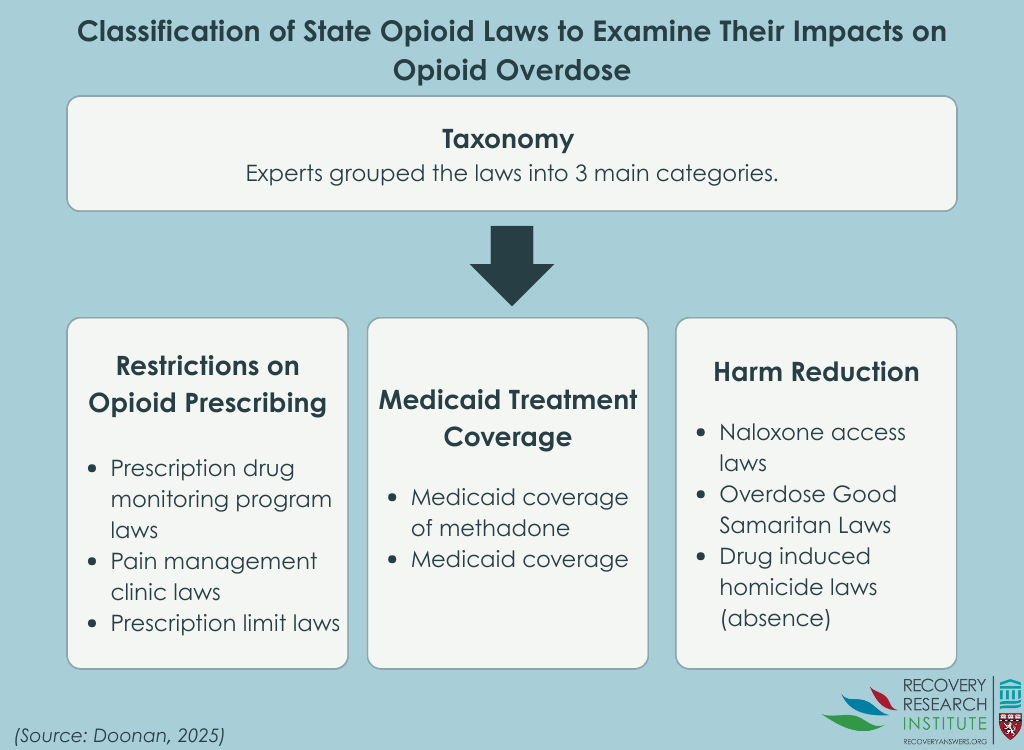

The researchers in this study examined whether enactment of state-level policies reduced the risk of opioid-related overdoses by developing a taxonomy and scoring system for a range of opioid-related laws. A panel of 56 experts were consulted to create consensus on the taxonomy, and they then scored the laws based on how helpful they perceived them to be. Panel members all had expertise in opioid-related policy and were from a variety of backgrounds, including academia, government, clinical practice, and advocacy.

Opioid-related laws from 50 US states and Washington D.C. were included. Data were obtained on the effective dates of 40 specific provisions of 8 types of laws for which longitudinal data were available. A variety of sources were used to obtain these data, including the Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System legal data repository, peer-reviewed literature, and reports. Laws were scored based on their enactment and varied from non-enactment (scored as 0) to full enactment (scored as 1).

The study team created the taxonomy (see Graphic below) by initially classifying 8 types of overdose laws and 50 provisions from these laws into 3 domains: opioid prescribing restrictions, “harm reduction”, and Medicaid treatment coverage. Then, they consulted the expert panel for feedback and consensus was achieved. The opioid prescribing restrictions domain included laws on prescription drug monitoring programs, pain clinics, and prescribing limits for acute pain. The “harm reduction” domain included laws on naloxone access, Good Samaritan, and the absence of drug-induced homicides. The Medicaid treatment coverage domain included laws on Medicaid methadone coverage and Medicaid expansion.

Next, 2 sets of scores for the provisions within each of these policy domains were created based on ratings of helpfulness from the expert panel. The panel rated each provision on a scale of 0-4, with 0 being very harmful and 4 being very helpful. The first set included “All Provisions,” where all expert-rated laws and provisions were included. The second set included the “Top 20 Provisions,” where the provisions that were rated most highly by the expert panel were included. These two sets were compared for their effectiveness in reducing risk for opioid-related overdoses, with the hypothesis that the Top 20 Provisions set would be just as strong a predictor of overdose than the All Provisions set, since they were rated to be among the most helpful at reducing overdose risk. Because findings were similar whether the study examined all provisions or just the top 20, we summarize only those from “All Provisions” (i.e., the entire set of policies).

Data for overdose deaths were obtained from the National Vital Statistics System, housed within the National Center for Health Statistics, using restricted-use files with information regarding detailed multiple cause of death mortality across all counties between 2013 and 2020. This system is based on national poisoning surveillance standards for opioid overdose. Information on race was also obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics mortality data and corresponding data on race within the greater population, which allowed the research team to compare effects between groups. Due to data availability, the 3 largest single race groups were included: non-Hispanic Black/African American people, Hispanic/Latino people of any race, and non-Hispanic White people.

Analyses controlled statistically for these variables at the county level: percent men; percent White/non-Hispanic population; percent Black/non-Hispanic population; percent Hispanic population; percent of the population ages 0–17, 18–24, 25–44, and 45–65; percent of families in poverty; percent of civilian labor force unemployed; and median household income. These data were obtained from the American Community Survey for the years 2012-2019. Additionally, researchers obtained data on the annual population density per 1,000 square miles, annual rates of death from all-cause mortality per 1,000 residents, and annual percentage of drugs positive for fentanyl within top 60 drugs seized by the Drug Enforcement Agency for each state to control for these variables as well. Such statistical adjustments help to isolate the effects of interest – i.e., whether enactment of opioid-related laws and provisions reduced risk of overdoses.

Analyses examined the associations between enactment of overdose-related provisions between 2012 – 2019 and the risk of opioid-related overdose deaths between 2013 and 2020 – the predictor and outcome were time-lagged meaning they examined the effects of opioid policy on overdose in the following year. The study also examined these associations among racial and ethnic subgroups from 1,485 counties. Analyses controlled for the covariates described above.

Naloxone (Narcan) distribution and other “harm reduction” policies decreased risk of overdose deaths, while opioid prescribing restriction policies and Medicaid treatment coverage policies initially increased risk

Overall, more opioid-related policies were enacted towards the later years of the study. The overall nationwide rate of opioid-involved deaths also almost tripled over the study period, from 8 deaths per 100,000 people in 2013 to 21 deaths per 100,000 people in 2020. Yet, the range varied substantially, from 0-1,755 deaths per county, with 29%-38% of counties having 0 deaths in any year (with fewer counties towards the end of the study period).

Between 2013 and 2020, enactment of laws from the “harm reduction” policy domain within a given year was associated with a 16% reduction in the risk of opioid-related overdose death in the subsequent year.

However, enactment of laws between 2013 and 2020 from the opioid prescribing restriction and Medicaid treatment coverage policy domains was associated with an increased risk of opioid-related overdose deaths. Specifically, enactment of laws from the opioid prescribing restriction domain was associated with a 24% increased risk of overdose death in the subsequent year. Enactment of laws from the Medicaid treatment coverage domain was associated with a 14% increased risk of overdose death in the subsequent year. Importantly, however, this differed over time. Between 2013 and 2016, enactment of laws from the opioid prescribing restriction domain and the Medicaid treatment coverage domain within a given year was associated with a 35% and 20% increased risk of opioid-related overdose death in the subsequent year, respectively. However, between 2017 and 2020, there were no associations between enactment of prescribing and Medicaid laws from these domains and risk of opioid overdose death.

Effects differed by race/ethnicity

For the racial and ethnic subgroup analyses, the protective effect found for naloxone availability and other harm reduction policies between 2013 and 2020 only remained for White individuals, while there was no association found for Black and Hispanic/Latino individuals. Likewise, the increase in risk found for the Medicaid treatment coverage policies only remained for White individuals and there was no association found for Black and Hispanic/Latino individuals. There were no differences for risk of opioid-related overdose death between racial and ethnic subgroups for opioid prescribing restriction policies.

The research team examined whether enactment of opioid-related policies reduced risk of opioid overdose death in counties nationwide, whether there were differences in their impact among ethnic and racial subgroups, and whether their impact varied over time.

Results showed that more naloxone availability and other policies focused on reduced consequences of opioid use decreased risk of opioid overdose death, while, somewhat surprisingly, opioid prescribing restriction policies and Medicaid treatment coverage policies increased risk. However, when examining their impact across time, the increase in overdose risk found for opioid prescribing restriction and Medicaid treatment coverage policies dissipated during the later years of study period to have no association – meaning there were no harms but no benefits either. The ethnic and racial subgroup analyses revealed that the decrease in risk from harm reduction policies and increase in risk from Medicaid treatment policies remained only for White individuals.

First, these findings add to other studies suggesting public health benefits from services that focus on reducing harmful consequences of drug use, including evidence that supervised consumption sites reduce rates of infectious disease and overdose deaths, harm reduction supply dispensing machines decrease the incidence of overdose deaths and HIV cases, and increased access to naloxone reduces opioid-related mortality.

The finding that the increase in overdose risk found for opioid prescribing restriction and Medicaid treatment coverage policies diminished to no effect during the later years of the study, while harm reduction policies maintained their beneficial effect across the entire study time period, suggests that these policies may have helped to alleviate some of the unintended consequences that resulted from opioid prescribing restriction and Medicaid treatment coverage policies earlier in the study. For instance, opioid restrictions may have resulted in more people (e.g., with chronic or severe pain) turning to synthetic opioids and heroin from an unregulated supply. Another possible explanation is that there may be a delay in the observed benefits from restricting opioid policies, with one study showing there may be up to a decade-long time lag between restrictions and prevention of opioid-related overdoses.

The finding that more Medicaid coverage was associated with initially increased overdose rates was also unexpected. It is possible that more Medicaid coverage for methadone increased overdose risk, as methadone—a full opioid agonist—has this potential. It is also possible that states expanded Medicaid coverage in response to worse overdose rates – for example, if states with more progressive drug laws have more urban areas and also were more likely to expand Medicaid, that could account for unexpectedly higher overdose rates. Notably, the analyses adjusted for many variables to try and account for this type of “selection bias”, but such approaches cannot account entirely for this possibility.

The results from the ethnic and racial subgroup analyses showing that the decrease in risk from harm reduction policies and increase in risk from Medicaid treatment policies remained only for White individuals suggests that there are potentially greater benefits and harms stemming from opioid-related policies for White individuals. This may be due to the epidemiological trends showing that the opioid overdose epidemic initially affected White people more than other ethnic and racial groups. However, greater investigation is needed into whether harm reduction policies benefit White people more to ensure equitable design and implementation of these policies, so that the maximum number of people benefit from these life-impacting opioid-related policies.

Naloxone (Narcan) availability and other policies to decrease opioid use consequences decreased risk of opioid overdose death, while opioid prescribing restriction policies and Medicaid treatment coverage policies unexpectedly increased risk. However, the increases for opioid prescribing restriction and Medicaid treatment coverage policies dissipated during the later years of study. The decrease in risk from harm reducing policies and increase in risk from Medicaid treatment policies remained only for White individuals, reflecting the potential for both greater benefits and harms for White people.

Doonan, S. M., Wheeler-Martin, K., Davis, C., Mauro, C., Bruzelius, E., Crystal, S., Mannes, Z., Gutkind, S., Keyes, K. M., Rudolph, K. E., Samples, H., Henry, S. G., Hasin, D. S., Martins, S. S., & Cerdá, M. (2025). How do restrictions on opioid prescribing, harm reduction, and treatment coverage policies relate to opioid overdose deaths in the United States in 2013–2020? An application of a new state opioid policy scale. International Journal of Drug Policy, 137. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2025.104713.

l

To address the opioid overdose crisis in the US, policymakers have enacted a variety of laws that target different drivers of the crisis or reduce associated harms. These include, as examples, laws on expanding Medicaid coverage of medication treatment for opioid use disorder, tracking opioid prescribing through Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs to intervene if an excess of prescriptions is detected, and increasing access to naloxone (commonly known by the brand name “Narcan”, a drug that reverses opioid-related overdoses). However, the impacts of these policies on actual rates of opioid overdose deaths are unclear, as is whether any potential impacts have changed over time or have differential impacts between racial groups.

Investigating the real-world impact of policies meant to prevent opioid overdose deaths can help policymakers understand if they are achieving the intended impact or if they may have unintended consequences. Researchers in this study examined whether enactment of opioid-related policies reduced risk of opioid overdose death, whether there were differences in their impact among ethnic and racial subgroups, and whether their impact varied over time. This research can help shed light on which types of policies are helpful for reducing opioid overdose deaths and which are unintentionally harmful, which can inform future policymaking efforts and save lives.

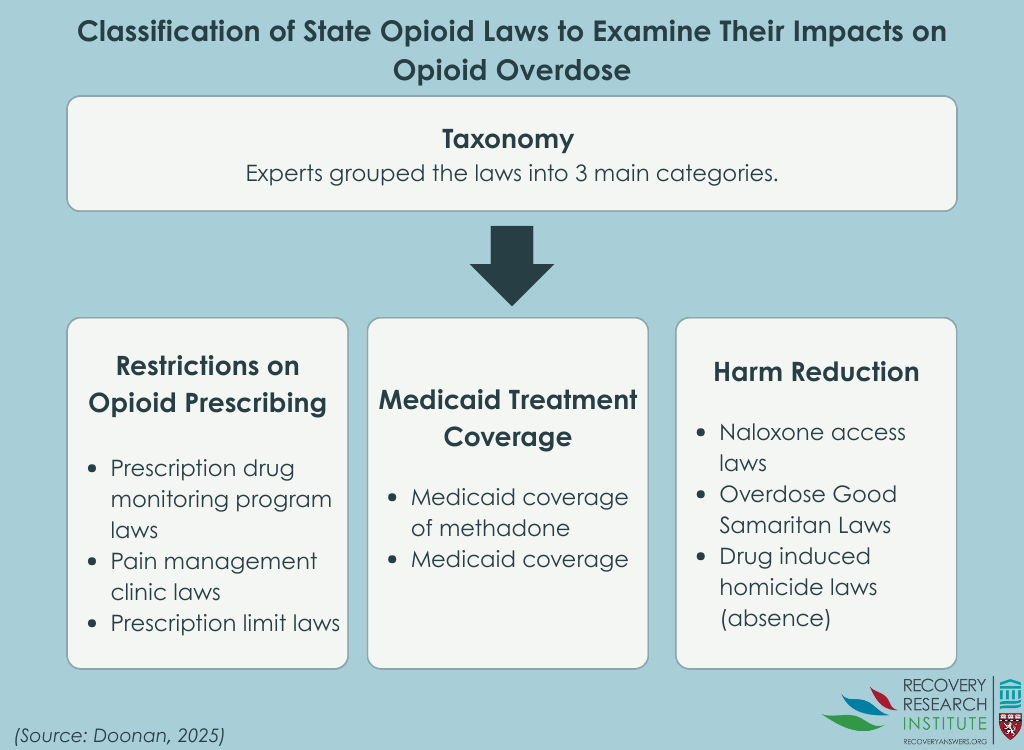

The researchers in this study examined whether enactment of state-level policies reduced the risk of opioid-related overdoses by developing a taxonomy and scoring system for a range of opioid-related laws. A panel of 56 experts were consulted to create consensus on the taxonomy, and they then scored the laws based on how helpful they perceived them to be. Panel members all had expertise in opioid-related policy and were from a variety of backgrounds, including academia, government, clinical practice, and advocacy.

Opioid-related laws from 50 US states and Washington D.C. were included. Data were obtained on the effective dates of 40 specific provisions of 8 types of laws for which longitudinal data were available. A variety of sources were used to obtain these data, including the Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System legal data repository, peer-reviewed literature, and reports. Laws were scored based on their enactment and varied from non-enactment (scored as 0) to full enactment (scored as 1).

The study team created the taxonomy (see Graphic below) by initially classifying 8 types of overdose laws and 50 provisions from these laws into 3 domains: opioid prescribing restrictions, “harm reduction”, and Medicaid treatment coverage. Then, they consulted the expert panel for feedback and consensus was achieved. The opioid prescribing restrictions domain included laws on prescription drug monitoring programs, pain clinics, and prescribing limits for acute pain. The “harm reduction” domain included laws on naloxone access, Good Samaritan, and the absence of drug-induced homicides. The Medicaid treatment coverage domain included laws on Medicaid methadone coverage and Medicaid expansion.

Next, 2 sets of scores for the provisions within each of these policy domains were created based on ratings of helpfulness from the expert panel. The panel rated each provision on a scale of 0-4, with 0 being very harmful and 4 being very helpful. The first set included “All Provisions,” where all expert-rated laws and provisions were included. The second set included the “Top 20 Provisions,” where the provisions that were rated most highly by the expert panel were included. These two sets were compared for their effectiveness in reducing risk for opioid-related overdoses, with the hypothesis that the Top 20 Provisions set would be just as strong a predictor of overdose than the All Provisions set, since they were rated to be among the most helpful at reducing overdose risk. Because findings were similar whether the study examined all provisions or just the top 20, we summarize only those from “All Provisions” (i.e., the entire set of policies).

Data for overdose deaths were obtained from the National Vital Statistics System, housed within the National Center for Health Statistics, using restricted-use files with information regarding detailed multiple cause of death mortality across all counties between 2013 and 2020. This system is based on national poisoning surveillance standards for opioid overdose. Information on race was also obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics mortality data and corresponding data on race within the greater population, which allowed the research team to compare effects between groups. Due to data availability, the 3 largest single race groups were included: non-Hispanic Black/African American people, Hispanic/Latino people of any race, and non-Hispanic White people.

Analyses controlled statistically for these variables at the county level: percent men; percent White/non-Hispanic population; percent Black/non-Hispanic population; percent Hispanic population; percent of the population ages 0–17, 18–24, 25–44, and 45–65; percent of families in poverty; percent of civilian labor force unemployed; and median household income. These data were obtained from the American Community Survey for the years 2012-2019. Additionally, researchers obtained data on the annual population density per 1,000 square miles, annual rates of death from all-cause mortality per 1,000 residents, and annual percentage of drugs positive for fentanyl within top 60 drugs seized by the Drug Enforcement Agency for each state to control for these variables as well. Such statistical adjustments help to isolate the effects of interest – i.e., whether enactment of opioid-related laws and provisions reduced risk of overdoses.

Analyses examined the associations between enactment of overdose-related provisions between 2012 – 2019 and the risk of opioid-related overdose deaths between 2013 and 2020 – the predictor and outcome were time-lagged meaning they examined the effects of opioid policy on overdose in the following year. The study also examined these associations among racial and ethnic subgroups from 1,485 counties. Analyses controlled for the covariates described above.

Naloxone (Narcan) distribution and other “harm reduction” policies decreased risk of overdose deaths, while opioid prescribing restriction policies and Medicaid treatment coverage policies initially increased risk

Overall, more opioid-related policies were enacted towards the later years of the study. The overall nationwide rate of opioid-involved deaths also almost tripled over the study period, from 8 deaths per 100,000 people in 2013 to 21 deaths per 100,000 people in 2020. Yet, the range varied substantially, from 0-1,755 deaths per county, with 29%-38% of counties having 0 deaths in any year (with fewer counties towards the end of the study period).

Between 2013 and 2020, enactment of laws from the “harm reduction” policy domain within a given year was associated with a 16% reduction in the risk of opioid-related overdose death in the subsequent year.

However, enactment of laws between 2013 and 2020 from the opioid prescribing restriction and Medicaid treatment coverage policy domains was associated with an increased risk of opioid-related overdose deaths. Specifically, enactment of laws from the opioid prescribing restriction domain was associated with a 24% increased risk of overdose death in the subsequent year. Enactment of laws from the Medicaid treatment coverage domain was associated with a 14% increased risk of overdose death in the subsequent year. Importantly, however, this differed over time. Between 2013 and 2016, enactment of laws from the opioid prescribing restriction domain and the Medicaid treatment coverage domain within a given year was associated with a 35% and 20% increased risk of opioid-related overdose death in the subsequent year, respectively. However, between 2017 and 2020, there were no associations between enactment of prescribing and Medicaid laws from these domains and risk of opioid overdose death.

Effects differed by race/ethnicity

For the racial and ethnic subgroup analyses, the protective effect found for naloxone availability and other harm reduction policies between 2013 and 2020 only remained for White individuals, while there was no association found for Black and Hispanic/Latino individuals. Likewise, the increase in risk found for the Medicaid treatment coverage policies only remained for White individuals and there was no association found for Black and Hispanic/Latino individuals. There were no differences for risk of opioid-related overdose death between racial and ethnic subgroups for opioid prescribing restriction policies.

The research team examined whether enactment of opioid-related policies reduced risk of opioid overdose death in counties nationwide, whether there were differences in their impact among ethnic and racial subgroups, and whether their impact varied over time.

Results showed that more naloxone availability and other policies focused on reduced consequences of opioid use decreased risk of opioid overdose death, while, somewhat surprisingly, opioid prescribing restriction policies and Medicaid treatment coverage policies increased risk. However, when examining their impact across time, the increase in overdose risk found for opioid prescribing restriction and Medicaid treatment coverage policies dissipated during the later years of study period to have no association – meaning there were no harms but no benefits either. The ethnic and racial subgroup analyses revealed that the decrease in risk from harm reduction policies and increase in risk from Medicaid treatment policies remained only for White individuals.

First, these findings add to other studies suggesting public health benefits from services that focus on reducing harmful consequences of drug use, including evidence that supervised consumption sites reduce rates of infectious disease and overdose deaths, harm reduction supply dispensing machines decrease the incidence of overdose deaths and HIV cases, and increased access to naloxone reduces opioid-related mortality.

The finding that the increase in overdose risk found for opioid prescribing restriction and Medicaid treatment coverage policies diminished to no effect during the later years of the study, while harm reduction policies maintained their beneficial effect across the entire study time period, suggests that these policies may have helped to alleviate some of the unintended consequences that resulted from opioid prescribing restriction and Medicaid treatment coverage policies earlier in the study. For instance, opioid restrictions may have resulted in more people (e.g., with chronic or severe pain) turning to synthetic opioids and heroin from an unregulated supply. Another possible explanation is that there may be a delay in the observed benefits from restricting opioid policies, with one study showing there may be up to a decade-long time lag between restrictions and prevention of opioid-related overdoses.

The finding that more Medicaid coverage was associated with initially increased overdose rates was also unexpected. It is possible that more Medicaid coverage for methadone increased overdose risk, as methadone—a full opioid agonist—has this potential. It is also possible that states expanded Medicaid coverage in response to worse overdose rates – for example, if states with more progressive drug laws have more urban areas and also were more likely to expand Medicaid, that could account for unexpectedly higher overdose rates. Notably, the analyses adjusted for many variables to try and account for this type of “selection bias”, but such approaches cannot account entirely for this possibility.

The results from the ethnic and racial subgroup analyses showing that the decrease in risk from harm reduction policies and increase in risk from Medicaid treatment policies remained only for White individuals suggests that there are potentially greater benefits and harms stemming from opioid-related policies for White individuals. This may be due to the epidemiological trends showing that the opioid overdose epidemic initially affected White people more than other ethnic and racial groups. However, greater investigation is needed into whether harm reduction policies benefit White people more to ensure equitable design and implementation of these policies, so that the maximum number of people benefit from these life-impacting opioid-related policies.

Naloxone (Narcan) availability and other policies to decrease opioid use consequences decreased risk of opioid overdose death, while opioid prescribing restriction policies and Medicaid treatment coverage policies unexpectedly increased risk. However, the increases for opioid prescribing restriction and Medicaid treatment coverage policies dissipated during the later years of study. The decrease in risk from harm reducing policies and increase in risk from Medicaid treatment policies remained only for White individuals, reflecting the potential for both greater benefits and harms for White people.

Doonan, S. M., Wheeler-Martin, K., Davis, C., Mauro, C., Bruzelius, E., Crystal, S., Mannes, Z., Gutkind, S., Keyes, K. M., Rudolph, K. E., Samples, H., Henry, S. G., Hasin, D. S., Martins, S. S., & Cerdá, M. (2025). How do restrictions on opioid prescribing, harm reduction, and treatment coverage policies relate to opioid overdose deaths in the United States in 2013–2020? An application of a new state opioid policy scale. International Journal of Drug Policy, 137. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2025.104713.