Medications for treating alcohol use disorder are proven to be safe and helpful. This study examined how prescriptions for these medications reduced risk for adverse events over time across the healthcare system

Medications for treating alcohol use disorder are proven to be safe and helpful. This study examined how prescriptions for these medications reduced risk for adverse events over time across the healthcare system

l

Alcohol use disorder and other forms of harmful alcohol use contribute substantially to global disease morbidity and mortality. Importantly, as with most substance use disorders, the majority of people who meet criteria for alcohol use disorder meet it at the milder end of spectrum. Whereas milder forms of the disorder can cause health, safety, and interpersonal harms, only a small proportion seek professional services and overall in the US, only 7% of those with alcohol use disorder receive any treatment and less than 2% received an FDA-approved alcohol use disorder medication. While many of these individuals might benefit from support, the majority who initiate and sustain remission do so without professional treatment. Among those with a primary alcohol problem in their first year of recovery, only 18% attended residential or outpatient treatment, and 11% received medication.

For those with more severe forms of alcohol use disorder, however, individualized combinations of professional and community-based service engagement may be needed to facilitate long-term recovery. There are several empirically supported treatments for alcohol use disorder including behavioral therapies and medications (i.e., naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram). What happens once individuals receive an alcohol use disorder medication is less certain.

A “cascade of care” framework can help to understand how often individuals with alcohol use disorder engage with treatments such as medications, how long they remain engaged with these treatments, and to what extent these various levels of engagement are associated with alcohol-related and other health outcomes. This study examined the “cascade of care” for individuals with alcohol use disorder within the healthcare system in British Columbia, Canada.

This study used a retrospective population-based cohort design. A random sample was taken of patients registered in the British Columbia provincial health insurance. Data from these patients were culled from multiple data sources (e.g., prescriptions dispensed at community pharmacies, provincial social assistance records, coroner’s services) to determine healthcare utilization and disease morbidity/mortality. Patients in the final sample (n=7231) were included if they were 1) diagnosed with moderate to severe alcohol use disorder and 2) received this diagnosis between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2019. Alcohol use disorder was determined using a case-finding algorithm based on the presence of a) ≥1 prescriptions for alcohol use disorder medications, b) ≥3 alcohol use disorder-related physician claims, or c) ≥1 alcohol use disorder-related hospitalizations/emergency department visits. AUD-related conditions were defined using relevant International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 and ICD-10 codes for alcohol dependence (i.e. moderate-to-severe alcohol use disorder), and complications of chronic alcohol use. Patients were excluded from the sample if they 1) were not diagnosed with an alcohol use disorder or were diagnosed with a mild alcohol use disorder (i.e. had 3 or less symptoms).

The focus of this study was to document annual changes in the prevalence of alcohol use disorder diagnosis and engagement in each stage of care for alcohol use disorder in British Columbia, Canada between 2015 and 2019. This research also sought to estimate the association between use of medications for alcohol use disorder each year and the likelihood of remission (determined by the presence of this diagnostic code in their chart) as well as the likelihood of experiencing adverse health events (i.e., emergency department visits, hospitalizations, or death) that same year. The authors used a six-stage cascade of care for alcohol use disorder in the current study. Each calendar year consisted of the following stages (1) diagnosed with moderate-to-severe alcohol use disorder; (2) linked to alcohol use disorder-related care (i.e., behavioral or pharmacological treatment); (3) initiated medication for alcohol use disorder; (4) retained in pharmacological alcohol use disorder treatment for ≥1 month; (5) retained in pharmacological alcohol use disorder treatment ≥3 months; and (6) retained in pharmacological alcohol use disorder treatment ≥6 months.

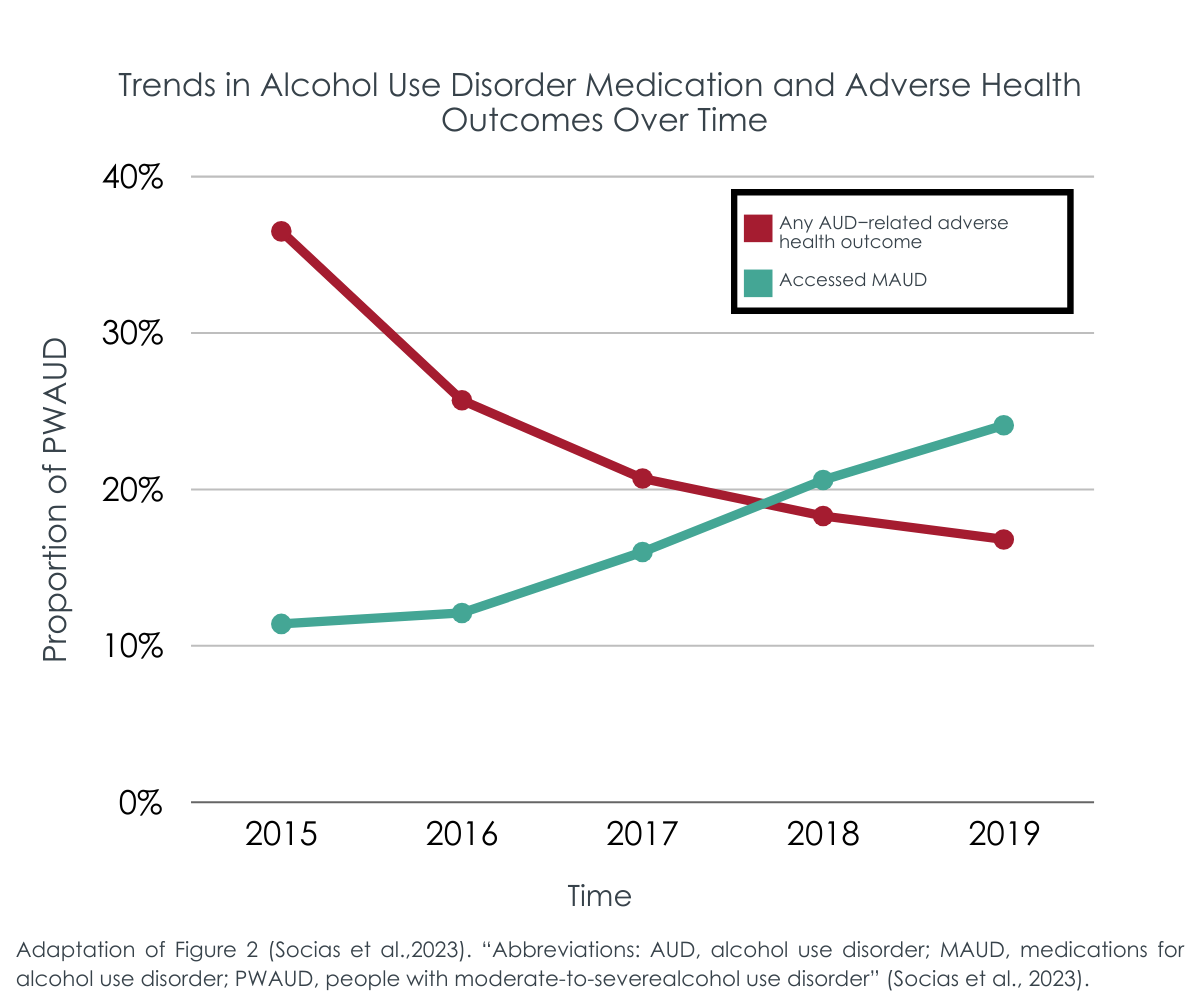

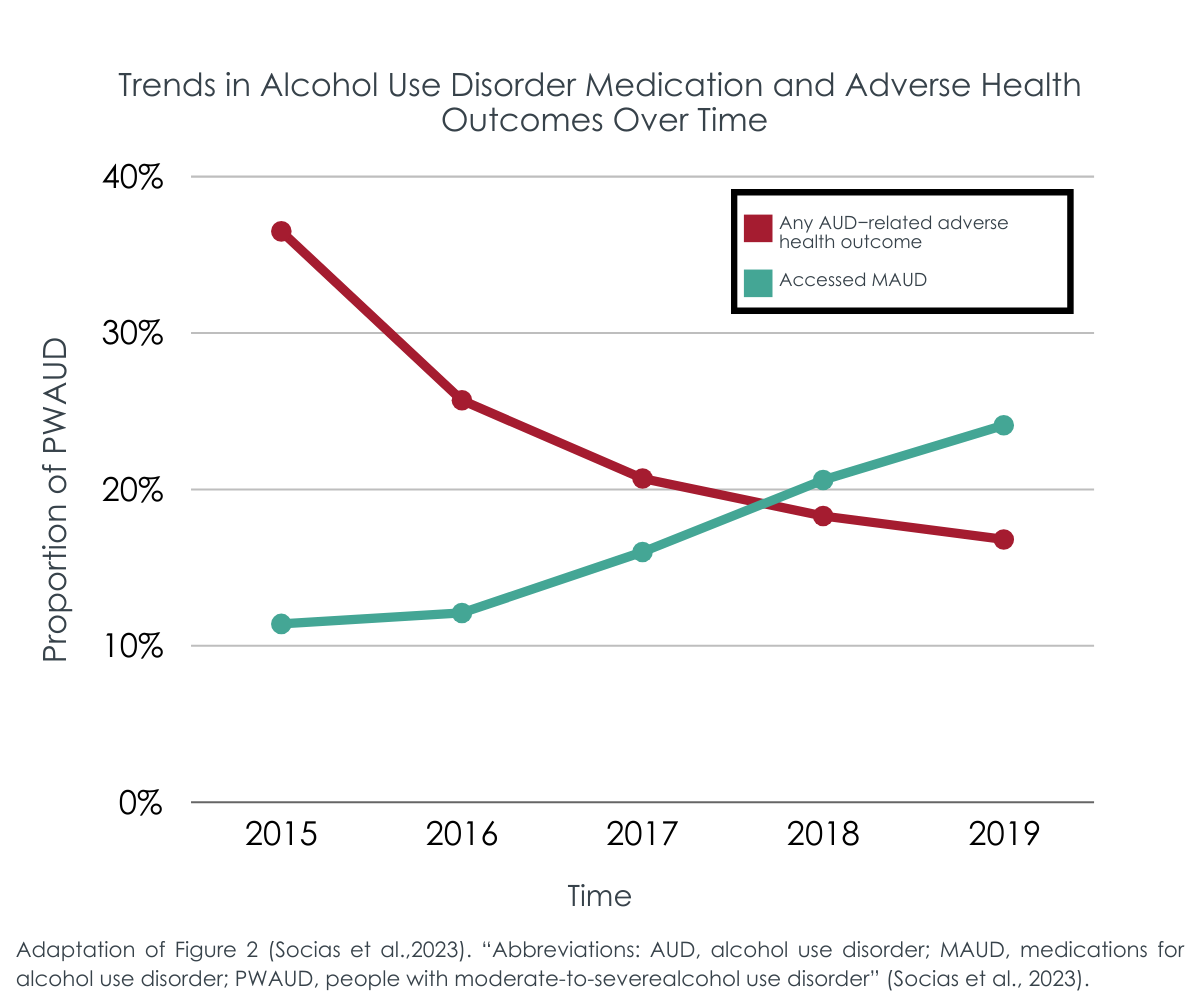

This study examined two research questions. First, how did the proportion of people with an alcohol use disorder reaching each stage of the alcohol use disorder cascade of care change over time. Second, to what extent were medications for alcohol use disorder associated with adverse health events (e.g., hospitalizations) due to alcohol use. Changes in the alcohol use disorder cascade of care were assessed via estimating the number of patients at each stage of the cascade of care per year (2015–2019). This involved using as denominator the number of diagnosed people with an alcohol use disorder in the relevant calendar year. Then researchers examined temporal trends of the proportion of patients achieving each stage of the AUD cascade and experiencing adverse health outcomes.

The study also examined the odds of experiencing adverse health events given use of medications for alcohol use disorder. Patients were considered as having accessed these medications if there was at least one medication for alcohol use disorder prescribed and dispensed by the pharmacy before an event of interest (e.g., hospitalization). Analyses adjusted for sociodemographic data (e.g., age) and comorbidities including health conditions like Hepatitis C and concurrent mental health disorder diagnoses. The researchers also adjusted for neighborhood social and material deprivation using a Quebec-specific version of the Neighborhood Deprivation Index.

About two-thirds of participants were 45+ years old (61.0%) and male (63.2%). Just over half (50.1%) had a concurrent mental health disorder, and 16.3% also had an additional substance use disorder (e.g., stimulant or opioid use disorder). Most participants lived in an urban/metropolitan environment (83.0%). Of the patients included in these analyses 36.9% received any medications for alcohol use disorder at some point during the 5-year study period.

Patients with lower severity more likely to receive medication overall.

Patients with alcohol use disorder were more likely to be prescribed medication for alcohol use disorder if they were younger, female, lived in metro areas, had a concurrent mental health disorder, and lived in communities with lower material deprivation. These individuals were also less likely to have another substance use disorder diagnosis or to have a history of incarceration or homelessness.

Receiving medication for alcohol use disorder associated with improved health outcomes.

Patients who were prescribed medications to treat their alcohol use disorder were more likely to achieve remission (3.3% medication vs. 1.2% no medication) and half as likely to experience adverse health events due to alcohol during the study period. Receiving the medication for longer periods of time (e.g., 6+ months) was associated with even greater reductions in the odds of adverse health events.

Many with alcohol use disorder not referred to treatment.

The number of patients who engaged with alcohol use disorder medication increased over the study period – 19.8% in 2015 to 48.2% in 2019. However, the overall proportion linked to any alcohol use disorder treatment decreased over time – from 80.4% in 2015 to 46.5% in 2019.

The results of this study provide key evidence regarding the additional utility of alcohol use disorder medications when patients remain on the medications for longer periods of time.

During the 5-year study period, patients prescribed medications to treat their alcohol use disorder were more likely to reach alcohol use disorder remission. These patients were also less likely to experience adverse health events due to alcohol (e.g., emergency department visits). These findings though may have been observed because patients who received medications were generally less severe, including lower likelihood of another substance use disorder (e.g., opioid, stimulant, etc.) as well as less likely to have histories of incarceration and homelessness. While the study accounted for as many measured characteristics as possible – to try and control statistically for this other explanation for the association between longer time receiving medication and better health outcomes (i.e., a “selection bias”) – there appears to be systematically greater levels of recovery capital in those who received medication. These models also did not control for other types of treatment or recovery support services, nor can they determine the degree to which patients adhered to the medication regimen – only that they received the medication from a pharmacy. Finally of note, while alcohol use disorder medications are generally associated with only modest benefits in randomized controlled trials, this naturalistic study examines the total effects on health outcomes, including the medication’s effects and any expectancy (placebo) effects as well.

The researchers also found that the proportion of patients with alcohol use disorder who received one of three approved medications – naltrexone, acamprosate, or disulfiram – increased over time while the overall percentage linked to any care decreased over time. Reasons for these diverging trends are unknown but likely to be explained by the unique context of Canada’s treatment guidelines and federally funded single payor system.

The constraints of the design in terms of drawing conclusions about medication benefits notwithstanding, the study also found that certain demographic factors were associated with decreased odds of receiving a prescription for alcohol use disorder medication, including residence in a more rural area and more severe clinical profiles overall. It is possible that different barriers may exist for these groups of people with alcohol use disorder that hindered them from accessing care. For example, evidence suggests that perceived social stigma may be a stronger potential barrier to seeking treatment for alcohol use disorder in primary care among people living in rural areas as word could get around the smaller community that they “have a problem”. It is important to point out that because this sample was derived from citizens of British Columbia, Canada, who were registered in provincial health insurance, healthcare access due to cost or lack of insurance was not a contributing factor to lack of treatment utilization.

Results of this research suggest that sustained engagement with medications for alcohol use disorders may help reduce the risk of experiencing adverse alcohol-related outcomes such as hospitalization although greater duration of medication use may reflect greater motivation for change and this study design cannot unravel these potential causes and effects. The researchers also found that the rate of initiation and retention in such treatment remained low throughout the 5-year study period. No more than 24% of patients diagnosed with a moderate to severe alcohol use disorder initiated pharmacological treatment in any given year of the study. Taken together these results underscore the need for more research on the real-world uptake and effects of alcohol use disorder medications. As part of this research, it is critical to examine potential disparities in access to empirically supported treatments, including but not limited to medications, and targets for future interventions to address any observed disparities.

Socias, M. E., Scheuermeyer, F. X., Cui, Z., Mok, W. Y., Crabtree, A., Fairbairn, N., … & Ti, L. (2023). Using a cascade of care framework to identify gaps in access to medications for alcohol use disorder in British Columbia, Canada, Addiction, doi: 10.1111/add.16273.

l

Alcohol use disorder and other forms of harmful alcohol use contribute substantially to global disease morbidity and mortality. Importantly, as with most substance use disorders, the majority of people who meet criteria for alcohol use disorder meet it at the milder end of spectrum. Whereas milder forms of the disorder can cause health, safety, and interpersonal harms, only a small proportion seek professional services and overall in the US, only 7% of those with alcohol use disorder receive any treatment and less than 2% received an FDA-approved alcohol use disorder medication. While many of these individuals might benefit from support, the majority who initiate and sustain remission do so without professional treatment. Among those with a primary alcohol problem in their first year of recovery, only 18% attended residential or outpatient treatment, and 11% received medication.

For those with more severe forms of alcohol use disorder, however, individualized combinations of professional and community-based service engagement may be needed to facilitate long-term recovery. There are several empirically supported treatments for alcohol use disorder including behavioral therapies and medications (i.e., naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram). What happens once individuals receive an alcohol use disorder medication is less certain.

A “cascade of care” framework can help to understand how often individuals with alcohol use disorder engage with treatments such as medications, how long they remain engaged with these treatments, and to what extent these various levels of engagement are associated with alcohol-related and other health outcomes. This study examined the “cascade of care” for individuals with alcohol use disorder within the healthcare system in British Columbia, Canada.

This study used a retrospective population-based cohort design. A random sample was taken of patients registered in the British Columbia provincial health insurance. Data from these patients were culled from multiple data sources (e.g., prescriptions dispensed at community pharmacies, provincial social assistance records, coroner’s services) to determine healthcare utilization and disease morbidity/mortality. Patients in the final sample (n=7231) were included if they were 1) diagnosed with moderate to severe alcohol use disorder and 2) received this diagnosis between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2019. Alcohol use disorder was determined using a case-finding algorithm based on the presence of a) ≥1 prescriptions for alcohol use disorder medications, b) ≥3 alcohol use disorder-related physician claims, or c) ≥1 alcohol use disorder-related hospitalizations/emergency department visits. AUD-related conditions were defined using relevant International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 and ICD-10 codes for alcohol dependence (i.e. moderate-to-severe alcohol use disorder), and complications of chronic alcohol use. Patients were excluded from the sample if they 1) were not diagnosed with an alcohol use disorder or were diagnosed with a mild alcohol use disorder (i.e. had 3 or less symptoms).

The focus of this study was to document annual changes in the prevalence of alcohol use disorder diagnosis and engagement in each stage of care for alcohol use disorder in British Columbia, Canada between 2015 and 2019. This research also sought to estimate the association between use of medications for alcohol use disorder each year and the likelihood of remission (determined by the presence of this diagnostic code in their chart) as well as the likelihood of experiencing adverse health events (i.e., emergency department visits, hospitalizations, or death) that same year. The authors used a six-stage cascade of care for alcohol use disorder in the current study. Each calendar year consisted of the following stages (1) diagnosed with moderate-to-severe alcohol use disorder; (2) linked to alcohol use disorder-related care (i.e., behavioral or pharmacological treatment); (3) initiated medication for alcohol use disorder; (4) retained in pharmacological alcohol use disorder treatment for ≥1 month; (5) retained in pharmacological alcohol use disorder treatment ≥3 months; and (6) retained in pharmacological alcohol use disorder treatment ≥6 months.

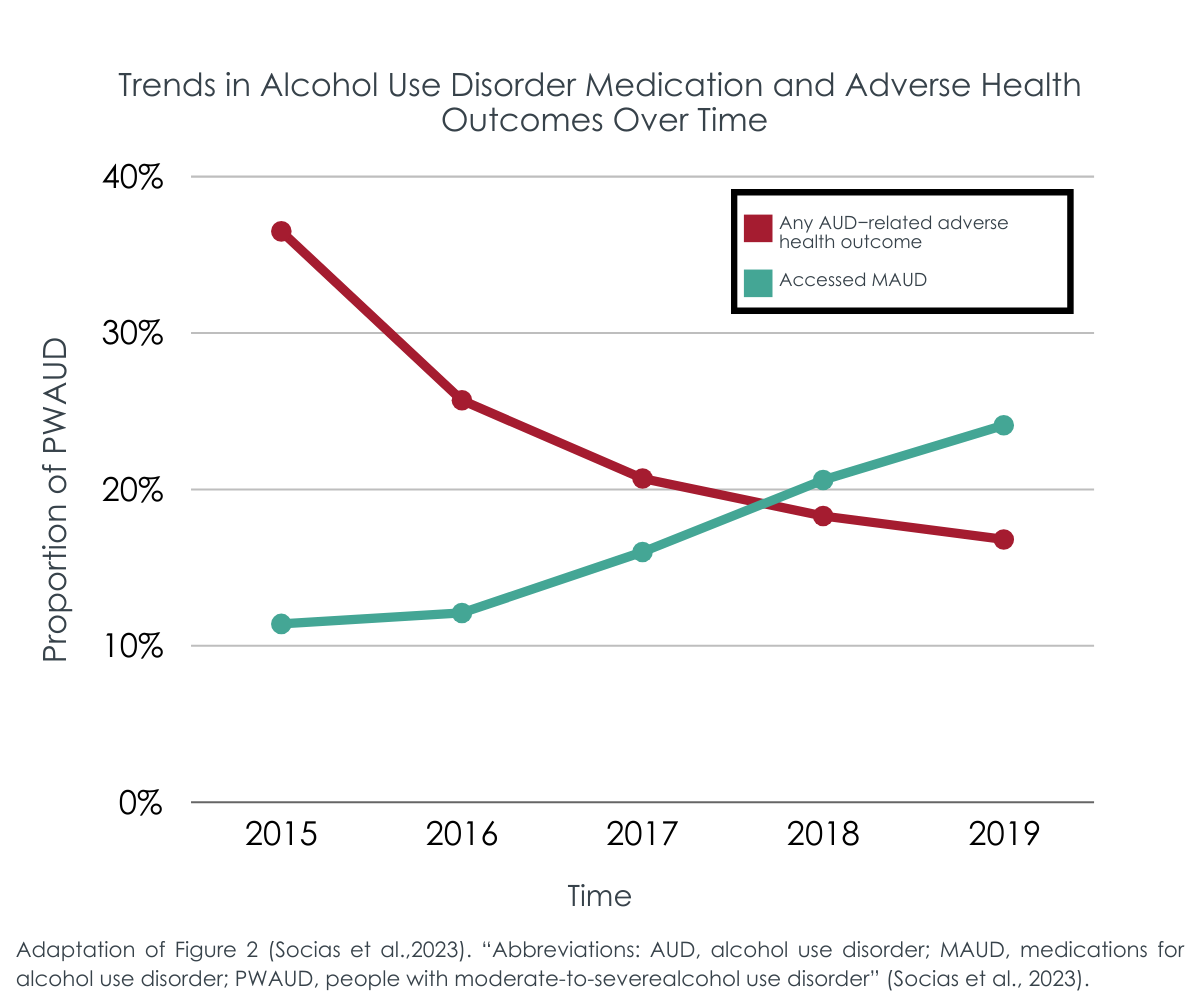

This study examined two research questions. First, how did the proportion of people with an alcohol use disorder reaching each stage of the alcohol use disorder cascade of care change over time. Second, to what extent were medications for alcohol use disorder associated with adverse health events (e.g., hospitalizations) due to alcohol use. Changes in the alcohol use disorder cascade of care were assessed via estimating the number of patients at each stage of the cascade of care per year (2015–2019). This involved using as denominator the number of diagnosed people with an alcohol use disorder in the relevant calendar year. Then researchers examined temporal trends of the proportion of patients achieving each stage of the AUD cascade and experiencing adverse health outcomes.

The study also examined the odds of experiencing adverse health events given use of medications for alcohol use disorder. Patients were considered as having accessed these medications if there was at least one medication for alcohol use disorder prescribed and dispensed by the pharmacy before an event of interest (e.g., hospitalization). Analyses adjusted for sociodemographic data (e.g., age) and comorbidities including health conditions like Hepatitis C and concurrent mental health disorder diagnoses. The researchers also adjusted for neighborhood social and material deprivation using a Quebec-specific version of the Neighborhood Deprivation Index.

About two-thirds of participants were 45+ years old (61.0%) and male (63.2%). Just over half (50.1%) had a concurrent mental health disorder, and 16.3% also had an additional substance use disorder (e.g., stimulant or opioid use disorder). Most participants lived in an urban/metropolitan environment (83.0%). Of the patients included in these analyses 36.9% received any medications for alcohol use disorder at some point during the 5-year study period.

Patients with lower severity more likely to receive medication overall.

Patients with alcohol use disorder were more likely to be prescribed medication for alcohol use disorder if they were younger, female, lived in metro areas, had a concurrent mental health disorder, and lived in communities with lower material deprivation. These individuals were also less likely to have another substance use disorder diagnosis or to have a history of incarceration or homelessness.

Receiving medication for alcohol use disorder associated with improved health outcomes.

Patients who were prescribed medications to treat their alcohol use disorder were more likely to achieve remission (3.3% medication vs. 1.2% no medication) and half as likely to experience adverse health events due to alcohol during the study period. Receiving the medication for longer periods of time (e.g., 6+ months) was associated with even greater reductions in the odds of adverse health events.

Many with alcohol use disorder not referred to treatment.

The number of patients who engaged with alcohol use disorder medication increased over the study period – 19.8% in 2015 to 48.2% in 2019. However, the overall proportion linked to any alcohol use disorder treatment decreased over time – from 80.4% in 2015 to 46.5% in 2019.

The results of this study provide key evidence regarding the additional utility of alcohol use disorder medications when patients remain on the medications for longer periods of time.

During the 5-year study period, patients prescribed medications to treat their alcohol use disorder were more likely to reach alcohol use disorder remission. These patients were also less likely to experience adverse health events due to alcohol (e.g., emergency department visits). These findings though may have been observed because patients who received medications were generally less severe, including lower likelihood of another substance use disorder (e.g., opioid, stimulant, etc.) as well as less likely to have histories of incarceration and homelessness. While the study accounted for as many measured characteristics as possible – to try and control statistically for this other explanation for the association between longer time receiving medication and better health outcomes (i.e., a “selection bias”) – there appears to be systematically greater levels of recovery capital in those who received medication. These models also did not control for other types of treatment or recovery support services, nor can they determine the degree to which patients adhered to the medication regimen – only that they received the medication from a pharmacy. Finally of note, while alcohol use disorder medications are generally associated with only modest benefits in randomized controlled trials, this naturalistic study examines the total effects on health outcomes, including the medication’s effects and any expectancy (placebo) effects as well.

The researchers also found that the proportion of patients with alcohol use disorder who received one of three approved medications – naltrexone, acamprosate, or disulfiram – increased over time while the overall percentage linked to any care decreased over time. Reasons for these diverging trends are unknown but likely to be explained by the unique context of Canada’s treatment guidelines and federally funded single payor system.

The constraints of the design in terms of drawing conclusions about medication benefits notwithstanding, the study also found that certain demographic factors were associated with decreased odds of receiving a prescription for alcohol use disorder medication, including residence in a more rural area and more severe clinical profiles overall. It is possible that different barriers may exist for these groups of people with alcohol use disorder that hindered them from accessing care. For example, evidence suggests that perceived social stigma may be a stronger potential barrier to seeking treatment for alcohol use disorder in primary care among people living in rural areas as word could get around the smaller community that they “have a problem”. It is important to point out that because this sample was derived from citizens of British Columbia, Canada, who were registered in provincial health insurance, healthcare access due to cost or lack of insurance was not a contributing factor to lack of treatment utilization.

Results of this research suggest that sustained engagement with medications for alcohol use disorders may help reduce the risk of experiencing adverse alcohol-related outcomes such as hospitalization although greater duration of medication use may reflect greater motivation for change and this study design cannot unravel these potential causes and effects. The researchers also found that the rate of initiation and retention in such treatment remained low throughout the 5-year study period. No more than 24% of patients diagnosed with a moderate to severe alcohol use disorder initiated pharmacological treatment in any given year of the study. Taken together these results underscore the need for more research on the real-world uptake and effects of alcohol use disorder medications. As part of this research, it is critical to examine potential disparities in access to empirically supported treatments, including but not limited to medications, and targets for future interventions to address any observed disparities.

Socias, M. E., Scheuermeyer, F. X., Cui, Z., Mok, W. Y., Crabtree, A., Fairbairn, N., … & Ti, L. (2023). Using a cascade of care framework to identify gaps in access to medications for alcohol use disorder in British Columbia, Canada, Addiction, doi: 10.1111/add.16273.

l

Alcohol use disorder and other forms of harmful alcohol use contribute substantially to global disease morbidity and mortality. Importantly, as with most substance use disorders, the majority of people who meet criteria for alcohol use disorder meet it at the milder end of spectrum. Whereas milder forms of the disorder can cause health, safety, and interpersonal harms, only a small proportion seek professional services and overall in the US, only 7% of those with alcohol use disorder receive any treatment and less than 2% received an FDA-approved alcohol use disorder medication. While many of these individuals might benefit from support, the majority who initiate and sustain remission do so without professional treatment. Among those with a primary alcohol problem in their first year of recovery, only 18% attended residential or outpatient treatment, and 11% received medication.

For those with more severe forms of alcohol use disorder, however, individualized combinations of professional and community-based service engagement may be needed to facilitate long-term recovery. There are several empirically supported treatments for alcohol use disorder including behavioral therapies and medications (i.e., naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram). What happens once individuals receive an alcohol use disorder medication is less certain.

A “cascade of care” framework can help to understand how often individuals with alcohol use disorder engage with treatments such as medications, how long they remain engaged with these treatments, and to what extent these various levels of engagement are associated with alcohol-related and other health outcomes. This study examined the “cascade of care” for individuals with alcohol use disorder within the healthcare system in British Columbia, Canada.

This study used a retrospective population-based cohort design. A random sample was taken of patients registered in the British Columbia provincial health insurance. Data from these patients were culled from multiple data sources (e.g., prescriptions dispensed at community pharmacies, provincial social assistance records, coroner’s services) to determine healthcare utilization and disease morbidity/mortality. Patients in the final sample (n=7231) were included if they were 1) diagnosed with moderate to severe alcohol use disorder and 2) received this diagnosis between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2019. Alcohol use disorder was determined using a case-finding algorithm based on the presence of a) ≥1 prescriptions for alcohol use disorder medications, b) ≥3 alcohol use disorder-related physician claims, or c) ≥1 alcohol use disorder-related hospitalizations/emergency department visits. AUD-related conditions were defined using relevant International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 and ICD-10 codes for alcohol dependence (i.e. moderate-to-severe alcohol use disorder), and complications of chronic alcohol use. Patients were excluded from the sample if they 1) were not diagnosed with an alcohol use disorder or were diagnosed with a mild alcohol use disorder (i.e. had 3 or less symptoms).

The focus of this study was to document annual changes in the prevalence of alcohol use disorder diagnosis and engagement in each stage of care for alcohol use disorder in British Columbia, Canada between 2015 and 2019. This research also sought to estimate the association between use of medications for alcohol use disorder each year and the likelihood of remission (determined by the presence of this diagnostic code in their chart) as well as the likelihood of experiencing adverse health events (i.e., emergency department visits, hospitalizations, or death) that same year. The authors used a six-stage cascade of care for alcohol use disorder in the current study. Each calendar year consisted of the following stages (1) diagnosed with moderate-to-severe alcohol use disorder; (2) linked to alcohol use disorder-related care (i.e., behavioral or pharmacological treatment); (3) initiated medication for alcohol use disorder; (4) retained in pharmacological alcohol use disorder treatment for ≥1 month; (5) retained in pharmacological alcohol use disorder treatment ≥3 months; and (6) retained in pharmacological alcohol use disorder treatment ≥6 months.

This study examined two research questions. First, how did the proportion of people with an alcohol use disorder reaching each stage of the alcohol use disorder cascade of care change over time. Second, to what extent were medications for alcohol use disorder associated with adverse health events (e.g., hospitalizations) due to alcohol use. Changes in the alcohol use disorder cascade of care were assessed via estimating the number of patients at each stage of the cascade of care per year (2015–2019). This involved using as denominator the number of diagnosed people with an alcohol use disorder in the relevant calendar year. Then researchers examined temporal trends of the proportion of patients achieving each stage of the AUD cascade and experiencing adverse health outcomes.

The study also examined the odds of experiencing adverse health events given use of medications for alcohol use disorder. Patients were considered as having accessed these medications if there was at least one medication for alcohol use disorder prescribed and dispensed by the pharmacy before an event of interest (e.g., hospitalization). Analyses adjusted for sociodemographic data (e.g., age) and comorbidities including health conditions like Hepatitis C and concurrent mental health disorder diagnoses. The researchers also adjusted for neighborhood social and material deprivation using a Quebec-specific version of the Neighborhood Deprivation Index.

About two-thirds of participants were 45+ years old (61.0%) and male (63.2%). Just over half (50.1%) had a concurrent mental health disorder, and 16.3% also had an additional substance use disorder (e.g., stimulant or opioid use disorder). Most participants lived in an urban/metropolitan environment (83.0%). Of the patients included in these analyses 36.9% received any medications for alcohol use disorder at some point during the 5-year study period.

Patients with lower severity more likely to receive medication overall.

Patients with alcohol use disorder were more likely to be prescribed medication for alcohol use disorder if they were younger, female, lived in metro areas, had a concurrent mental health disorder, and lived in communities with lower material deprivation. These individuals were also less likely to have another substance use disorder diagnosis or to have a history of incarceration or homelessness.

Receiving medication for alcohol use disorder associated with improved health outcomes.

Patients who were prescribed medications to treat their alcohol use disorder were more likely to achieve remission (3.3% medication vs. 1.2% no medication) and half as likely to experience adverse health events due to alcohol during the study period. Receiving the medication for longer periods of time (e.g., 6+ months) was associated with even greater reductions in the odds of adverse health events.

Many with alcohol use disorder not referred to treatment.

The number of patients who engaged with alcohol use disorder medication increased over the study period – 19.8% in 2015 to 48.2% in 2019. However, the overall proportion linked to any alcohol use disorder treatment decreased over time – from 80.4% in 2015 to 46.5% in 2019.

The results of this study provide key evidence regarding the additional utility of alcohol use disorder medications when patients remain on the medications for longer periods of time.

During the 5-year study period, patients prescribed medications to treat their alcohol use disorder were more likely to reach alcohol use disorder remission. These patients were also less likely to experience adverse health events due to alcohol (e.g., emergency department visits). These findings though may have been observed because patients who received medications were generally less severe, including lower likelihood of another substance use disorder (e.g., opioid, stimulant, etc.) as well as less likely to have histories of incarceration and homelessness. While the study accounted for as many measured characteristics as possible – to try and control statistically for this other explanation for the association between longer time receiving medication and better health outcomes (i.e., a “selection bias”) – there appears to be systematically greater levels of recovery capital in those who received medication. These models also did not control for other types of treatment or recovery support services, nor can they determine the degree to which patients adhered to the medication regimen – only that they received the medication from a pharmacy. Finally of note, while alcohol use disorder medications are generally associated with only modest benefits in randomized controlled trials, this naturalistic study examines the total effects on health outcomes, including the medication’s effects and any expectancy (placebo) effects as well.

The researchers also found that the proportion of patients with alcohol use disorder who received one of three approved medications – naltrexone, acamprosate, or disulfiram – increased over time while the overall percentage linked to any care decreased over time. Reasons for these diverging trends are unknown but likely to be explained by the unique context of Canada’s treatment guidelines and federally funded single payor system.

The constraints of the design in terms of drawing conclusions about medication benefits notwithstanding, the study also found that certain demographic factors were associated with decreased odds of receiving a prescription for alcohol use disorder medication, including residence in a more rural area and more severe clinical profiles overall. It is possible that different barriers may exist for these groups of people with alcohol use disorder that hindered them from accessing care. For example, evidence suggests that perceived social stigma may be a stronger potential barrier to seeking treatment for alcohol use disorder in primary care among people living in rural areas as word could get around the smaller community that they “have a problem”. It is important to point out that because this sample was derived from citizens of British Columbia, Canada, who were registered in provincial health insurance, healthcare access due to cost or lack of insurance was not a contributing factor to lack of treatment utilization.

Results of this research suggest that sustained engagement with medications for alcohol use disorders may help reduce the risk of experiencing adverse alcohol-related outcomes such as hospitalization although greater duration of medication use may reflect greater motivation for change and this study design cannot unravel these potential causes and effects. The researchers also found that the rate of initiation and retention in such treatment remained low throughout the 5-year study period. No more than 24% of patients diagnosed with a moderate to severe alcohol use disorder initiated pharmacological treatment in any given year of the study. Taken together these results underscore the need for more research on the real-world uptake and effects of alcohol use disorder medications. As part of this research, it is critical to examine potential disparities in access to empirically supported treatments, including but not limited to medications, and targets for future interventions to address any observed disparities.

Socias, M. E., Scheuermeyer, F. X., Cui, Z., Mok, W. Y., Crabtree, A., Fairbairn, N., … & Ti, L. (2023). Using a cascade of care framework to identify gaps in access to medications for alcohol use disorder in British Columbia, Canada, Addiction, doi: 10.1111/add.16273.