Jobs and friends: Markers of well-being among American Indian adults

American Indian and Alaska Native adults have high rates of substance use and substance use disorders as compared to the general US population. There is a lack of understanding of what addiction prevention, treatment, and recovery supports are most beneficial to this population group. As a result, scientists have partnered with these communities to create culturally sensitive programs adapted from existing empirically supported interventions. While there is increased research on peer-based recovery supports for individuals with substance use and mental health disorders, some populations may benefit more than others. Thus, research can help determine whether and, if so, how to leverage these services to improve American Indian engagement and outcomes given their unique clinical and cultural needs. This study examined short-term well-being outcomes, including substance use, among American Indian individuals who participated in the Transitional Recovery and Culture (TRAC) Program, a peer recovery support program for American Indian individuals.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

American Indian and Alaska Native adults have very high rates of substance use and substance use disorders as compared to the general US population and there is a lack of understanding of what addiction prevention, treatment, and recovery services are most beneficial to this population group. As well, research suggests that individuals in these communities may have specific needs to address in prevention and treatment work, including spirituality, trauma and loss, and engaging in traditional cultural activities, and thus tailored resources may be particularly helpful. Peer recovery supports are non-clinical approaches that include peers (individuals with lived experience relevant to the target group) who provide mentoring, education, and other supports for individuals seeking help. Use of peers in addiction treatment and recovery is a growing form of recovery support in the US and elsewhere.

Recent evidence suggests peer recovery supports are effective, although some populations may benefit more than others and the way these programs are tailored seems to matter in producing successful outcomes. To explore potential gains from using a peer support model in American Indian communities, this study examined short-term well-being outcomes among American Indian participants, who participated in a type of Peer Recovery Support program developed for this population, the Transitional Recovery and Culture (TRAC) Program. Specifically, this study addressed the following: (1) whether well-being resources and indicators of well-being differed between TRAC participants who completed a six-month follow-up and those who did not, (2) the level of change of resources between intake and 6-month follow-up, and (3) which resources were associated with improvements in the four primary domains of Spiritual, Physical, Emotion, and Mental Health and whether multiple domains were improved (i.e., “balanced recovery”).

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was an analysis of a subset of data from 442 American Indian participants living in Montana and Wyoming and who participated in the Transitional Recovery and Culture (TRAC) program (2014-2019). This study used data from the 214 participants who completed the 6-month TRAC program. The authors were interested in within-person changes, i.e., changes among TRAC participants between baseline and 6-months later, a time period the authors refer to as “short-term recovery”.

Figure 1.

The Transitional Recovery and Culture Program consisted primarily of the use of peer mentors who identified as American Indian. The TRAC program recognizes many pathways to well-being and recovery; talking circles, wellbriety meetings, spiritual gatherings, sweat lodges, physical fitness, housing assistance, food assistance, education and employment assistance, transportation, and spiritual and cultural support. The program emphasizes a holistic recovery approach (p. 2): “A commitment and choice of every ‘unique’ and ‘sacred’ individual to make a personal change in their life through self or supported services in response to maintaining a ‘holistic’ healthy and productive lifestyle. This is ultimately accomplished through a lifestyle that is balanced through mental, physical, social, emotional, and spiritual well-being in harmony with one’s chosen culture and identity.” In this study, the peer mentors were used to collect the outcome data from participants.

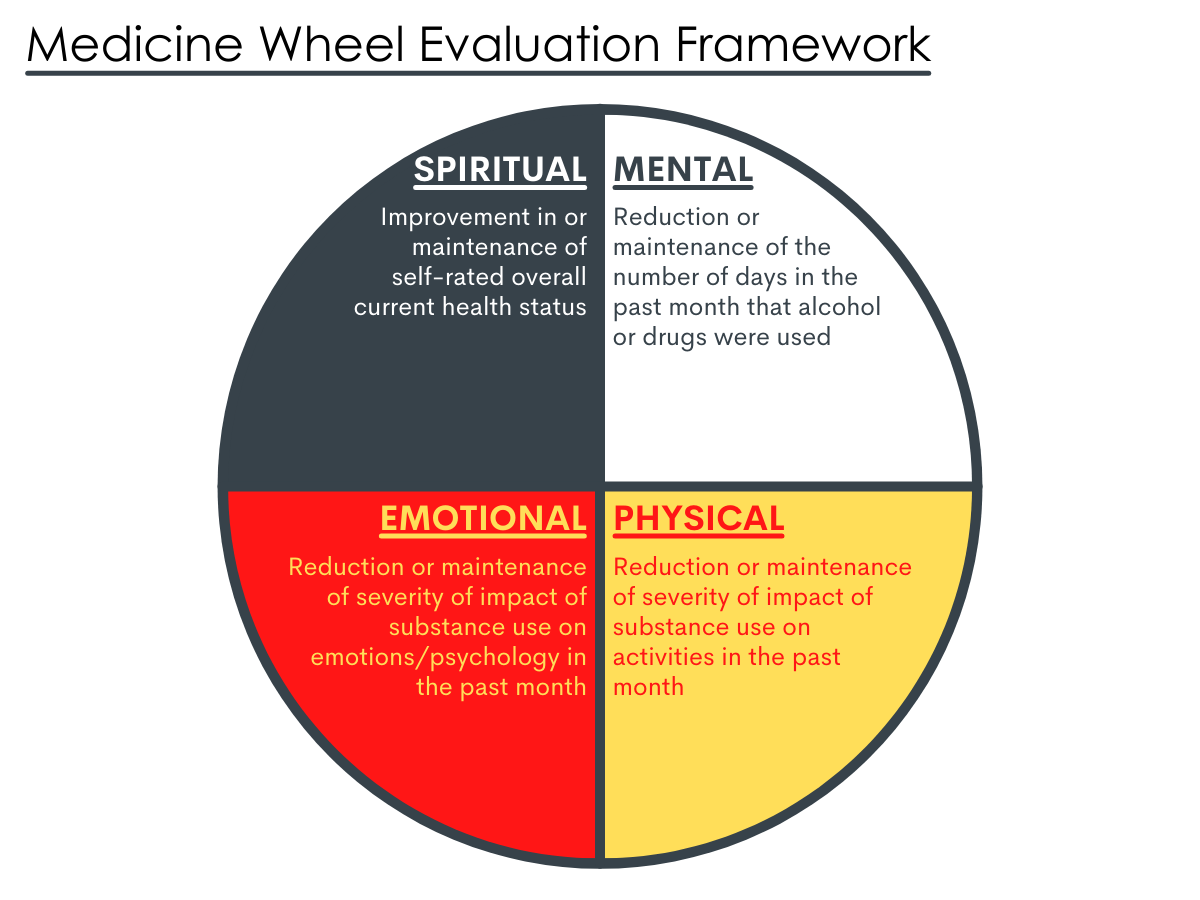

The Medicine Wheel Evaluation Framework was used to evaluate outcomes of the TRAC program as it aligns with the goal of TRAC (and peer recovery support programs more broadly): to restore balance in four primary domains in an individual’s life as these are the primary domains considered to be affected by substance use: (1) Spiritual health, (2) Physical health, (3) Emotional health, and (4) Mental health. Spiritual health was assessed by self-rated overall current health status, Physical health was assessed by the impact of substance use on activities in the past month, Emotional health was assessed by impact of substance use on emotion/psychology in the past month, and Mental health was assessed by number of days of alcohol/drug use in the past month. Measuring these four domains produces an overall score of 0-4 with 1 or 0 in each domain: A score of 1 in a domain indicates self-reported improvement or maintenance while a 0 indicates worsening outcomes in that domain. Based on these scores, the authors determined one’s level of balance of recovery during the TRAC program. That is, a change in 0-2 components was considered “poorly balanced” recovery while changes in 3-4 components were considered “highly balanced” recovery.

Figure 2. The Medicine Wheel Evaluation Framework as applied to study outcomes of interest. Figure adapted from Atlantic Council for International Cooperation, 2018

The authors also collected six types of resources among participants (labeled “Recovery Capital”) using the Government Performance and Response Act Measures. They measured three external resources: change in (1) occupation, (2) income, and (3) housing status. They also measured three internal resources: (1) change in self-help group attendance, (2) change in interaction with supportive friends/family, and (3) receipt of TRAC services at 6 months (i.e., continued engagement in TRAC program). As with the Medicine Wheel Scoring, a score of 1 indicates improvement or maintenance while a 0 indicates worsening outcomes on that factor.

The authors used their categorization of poorly versus highly balanced recovery (changes in 0-2 components versus changes in 3-4 components, respectively) to examine which resources were related to recovery balance changes from baseline to 6 months. In order to try and isolate the effect of resources on recovery outcomes, they controlled statistically for several variables including age, gender, violence/trauma experience, and community location.

The majority of the 214 participants were female (69%), 38 years or older, and had a history of trauma/violence (75%). The average monthly income was $895 (SD = $4,196) and only 39% were in training or employed. Notably, the substance use among the sample was extremely low or non-existent at baseline with participants engaging in 0.19 days of use at baseline (97% reported 0 days of use), indicating these were potentially participants without a diagnosed substance use disorder, but perhaps at risk of developing one.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Several Characteristics predicted sustained engagement in TRAC: Participants who remained engaged changed across several resources between intake and six-month follow-up.

Females, those recruited from the urban location, those with higher income, and those who rated lower psychological/emotional impact of substances were significantly more likely to complete the TRAC 6-month assessment (51% completed).

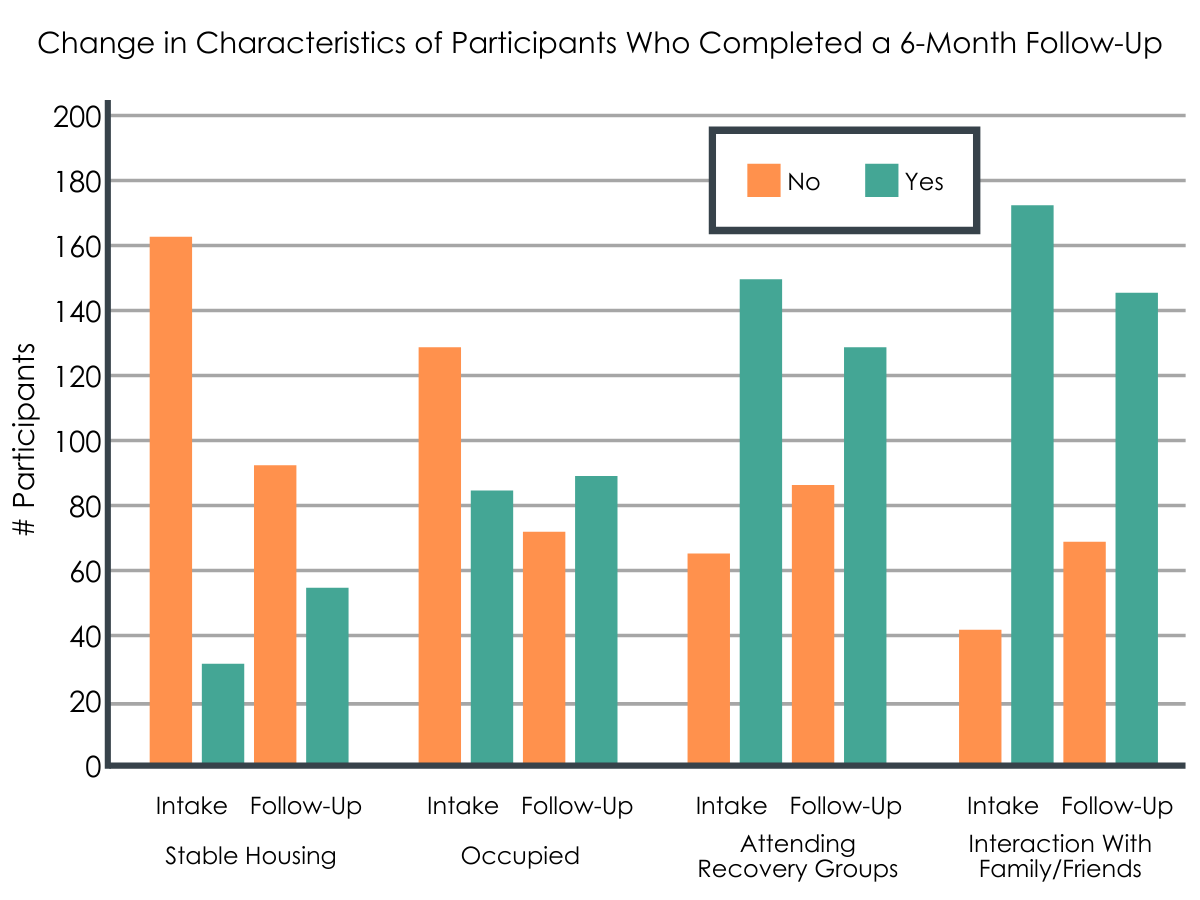

Participants who remained engaged in the TRAC program were more likely to have stable housing, be engaged with school, work, or training (“Occupied”), reduce substance use, and surprisingly, decreased interactions with supportive family/friends (although notably, those who remained in the program had higher overall levels of interactions than those who left the program). Participants also experienced a reduction in impact on activity and psychological/emotional impact, indicating improved physical and emotional health on the Medicine Wheel.

Figure 3. Changes in characteristics of participants who completed a 6-month follow-up. Those with no stable housing decreased, while those with stable housing increased. Not in school/work/training decreased, while being in school/work/training increased. Attending recovery groups increased, and interaction with family/friends decreased.

Resources and “balanced” recovery.

At the 6-month follow-up, less than half of the participants (92) had high balanced recovery (improved or stable in 3-4 components of the Medicine Wheel Evaluation Framework), while 122 had poorly balanced recovery (improved or stable in 0-2 components of the Medicine Wheel Evaluation Framework).

There were three significant positive predictors of a highly balanced short-term recovery score among those who stayed in the program: (1) Improving or maintaining occupation appeared the most important of the three resulting in over 6 times the odds of those who did not have an occupation (adjusted Odds Ratio = 6.73); (2) interacting with supportive family or friends increased the odds over 4 times compared to those who did not (adjusted Odds Ratio = 4.66); receiving TRAC services at follow-up doubled the odds as compared to those who were no longer receiving services (adjusted Odds Ratio = 2.25). Finally, one unanticipated finding is that a decline in stable housing was significantly associated with highly balanced recovery.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study examined a variety of important life domain changes over time in 214 American Indians in the TRAC program, a type of peer recovery support service designed specifically to engage American Indians in need of addiction prevention, treatment, or recovery services. The study found that 6-month outcomes among participants who remained in the program were primarily positive, although it is worth noting that the current study design (pre-post, single group) does not allow for statements of effectiveness of the program.

Participants in the program had built resources through increasing interactions with family and friends and increasing their work or training engagement. Although not all participants had a “highly balanced” recovery across the four recovery domains of interest in the study, i.e., sustaining positive behaviors or making more changes, those that did were more likely to have improved/maintained their occupation, had increased interaction with supportive family/friends, and had continued to engage in the TRAC program.

These findings highlight the potential importance of these specific resources in achieving overall well-being and high quality of life. The findings also suggest how the TRAC program, or peer recovery support services more broadly which focus on increasing aspects of recovery capital such as jobs or friends, facilitate the recovery process by enabling access to these sources of recovery capital. In doing so, the TRAC program represents an opportunity to not only improve the lives of its community members, but of the community more broadly, fostering healthy connections and relationships.

And yet, not all participants experienced “highly balanced” recovery at the 6-month mark; over half were considered in “low balanced recovery”, as having only achieved positive outcomes in up to 2 of the 4 recovery domains of interest. This is consistent with other research findings that there are individuals, possibly with more severe resource gaps or barriers that the TRAC program (or other peer recovery support programs) cannot reach. As well, given the relatively short time period of the study, it suggests that 6 months may not be enough time for all individuals to achieve substantial capital gains across all domains of their lives. Additionally, the study does not report on participant substance of choice or addiction severity which may be a key factor in retaining participants in the program or in making a number of changes across the 4 domains of the Medicine Wheel, areas for future research to address.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This sample appeared to have lower substance use than would typically be expected in a sample with substance use disorders (i.e., less than 1 day of substance use in the past 30 days when they entered the study, on average); thus, although the findings are positive especially for prevention work, less is understood about how these findings might translate to treatment or recovery work.

- There was a large amount of missing data: because only 51% completed the 6-month follow-up, there may be participant retention bias in that participants who stayed in the program did so as a result of their particular demographic profile. That is, in this study females and possibly those with higher baseline recovery capital were more likely to remain in the study, and thus did much better than those who did not stay in the program. Yet, models that controlled for sex did not find a significant difference for females versus males and no models controlled for baseline resources (e.g., income), suggesting that the impact of study attrition on the findings here is unknown.

- The Medicine Wheel Evaluation Framework and the other quantitative approaches used in the analysis result in missing data and miss some nuances of understanding recovery outcomes: most of the included variables were categorized into 0 or 1 (binary approach) which misses assessment of degrees or severity of change or problems.

- The Medicine Wheel Evaluation Framework also assumes an equal weight to all life domains, which may not be a valid representation across the sample; for example, improvement in one domain may be more important than improvement in another domain and this may vary by individual characteristics of participants.

BOTTOM LINE

This study examined 214 American Indians in the TRAC program, a type of peer support, and found that participants had built resources through reducing substance use, increasing stable housing, and increased their work or training engagement. These findings highlight how peer supports which focus on increasing aspects of internal and external resources such as jobs or friends, may improve one’s well-being by enabling access to these sources. Indeed, the study provides an important example of how peer support services could be adapted in culturally sensitive ways; future research should address the relative effectiveness of these adaptations.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: These findings highlight the importance of supportive friends and family in the recovery process and also illustrate the dynamic and interactive role of all forms of recovery capital in this process. Changes can be slow and can occur in multiple domains of one’s life and at different times in the process; linkages to a variety of services (e.g., trauma therapy, job skills training) that meet an individual’s particular needs is vital. As well, the findings suggest a continued need for some populations to be engaged in some type of community-level support, even 6-months after initiating an intervention or treatment.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Connecting individuals to culturally appropriate supports and resources which address their most immediate needs is vital to building recovery capital and ensuring their continued motivation and success. Providers and systems should be part of the bridge that connects patients to needed services. The use of the Medicine Wheel Evaluation – which captures key elements of quality of life including spiritual, emotional, mental, and physical health – may be a useful tool in this regard, or other evidence-based tools which assess internal and external supports of clients. Yet, the findings also demonstrate the need to tailor these recommendations and supports to the particular patient needs as not all patients will benefit from the same type of programming.

- For scientists: Although these findings are largely positive, the study highlights a number of future areas for research to address. First, given that less than half of the participants experienced a highly balanced recovery at 6-months, future work should address barriers to recovery capital, even within a peer recovery support program, especially for those with low initial recovery capital. As well, research should focus on recovery processes over a longer time period to identify how recovery capital and recovery outcomes develop at different paces for some individuals. Studies which examine which components of the TRAC program (or similar programs) were most highly used and successful are also necessary to fully understand the mechanisms of behavior change these programs effectively target. Finally, this study primarily used binary indicators of recovery changes and future research should attempt to capture more nuanced and possibly qualitative information to better understand the particular processes between individuals, peer recovery supports, and the larger community.

- For policy makers: As policy stakeholders agree that the recovery construct captures several domains of functioning and well-being, if public health systems are fully funded to better treat an individual as a whole person, then it seems necessary to facilitate strong linkages between health and support services. These linkages should address individuals’ most immediate needs and reduce structural barriers to living a full life, which should then also improve their recovery outcomes. Funding and policy efforts should be directed to engaging providers and systems in creating a bridge that connects patients to needed services.

CITATIONS

Kelley, A., Steinberg, R., McCoy, T. P., Pack, R., & Pepion, L. (2021). Exploring recovery: Findings from a six-year evaluation of an American Indian peer recovery support program. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 221, 108559. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108559