“Meeting young people where they’re at”: Integrating addiction services into primary care for young people who use substances

Adolescents and young adults with substance use disorder are notoriously difficult to engage and retain in treatment. Integrating addiction services into primary care may help reach more young people by meeting healthcare needs that include but are not limited to their substance use, which may improve engagement and retention. Researchers in this study described and evaluated the first 30 months of an integrated primary care clinic for young people who use substances.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

In 2019, 4.3 million (17.2%) adolescents (12-17 years old) used illicit drugs in the past year. Among emerging adults (18-25 years old), there were 13.5 million (39.1%) that reported using illicit drugs in the past year. Although using an illicit substance does not directly cause a substance use disorder, ongoing problem use and the chances of developing a substance use disorder increase when use is initiated during earlier life stages. Emerging adults, both when defined as 18-25 or 18-29 years old, have the highest rates of substance use disorder compared to their younger and older counter parts. If a substance use problem or disorder does develop during adolescence or emerging adulthood, earlier treatment is associated with shorter substance use disorder careers while entering recovery as a young, versus older, adult is associated with better quality of life. Providing targeted services for young people who use substances or have a substance use disorder may increase their long-term health and wellness. However, this age group is challenging to retain in treatment, with nearly a third dropping out of outpatient treatment prior to completion. Historically poor engagement and retention among adolescents and young adults signals the need for treatment and recovery services tailored to developmental realities of this population.

One common theme in addiction treatment, generally, is to meet people “where they are at”, an axiom describing person-centered care. One place “where they are not”, however, despite often meeting criteria for substance use disorder, is specialty addiction treatment services, because young people often do not perceive a need or desire to access such services at this stage of their substance involvement. Consequently, finding ways to engage with adolescents and emerging adults sooner in their substance use disorder trajectory may be key to enhancing their substance use and other health outcomes.

One way this has sought to be done is to create a centralized medical home for young people, where they can receive not only their usual medical services but also be screened for alcohol and other drug use and related problems and hopefully begin a conversation that can destabilize emerging addiction patterns sooner, prevent severe difficulties, and lead to sooner remission if they exhibit substance use disorder. Thus, primary care-based models of addressing substance use may provide additional youth benefits such as: identifying youth with infrequent use to prevent the development of a substance use disorder, providing counseling to minimize harms associated with substance use, and providing accessible substance use disorder treatment as needed outside of the more typical specialty addiction treatment services system.

Building on models of primary care-based addiction treatment for adults, this study used a retrospective evaluation design to explore the demographics, engagement and re-engagement, and social determinants of health among patients of CATALYST, a clinic with addiction treatment services nested within primary care for those under 25 years of age.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

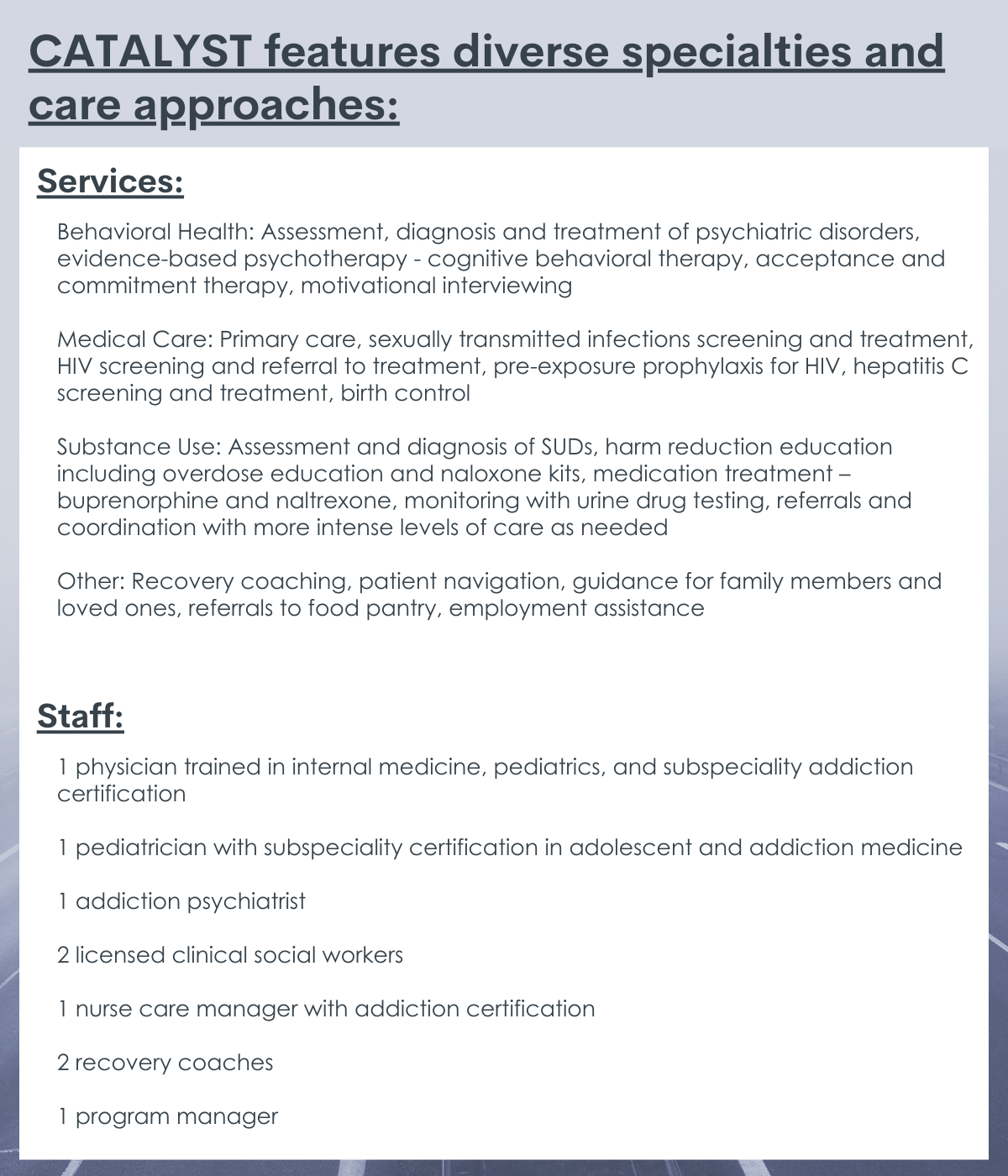

This study was a retrospective evaluation of the Center for Addiction Treatment for Adolescents/Young Adults Who Use Substances (CATALYST), which was founded in 2016 at Boston Medical Center to provide a range of clinical services for young people who use substances. Services include behavioral health, medical care, substance use services, and miscellaneous needs (e.g., social determinants navigation). The evaluation included a review of patient electronic health records from July 2016 to December 2018 (2.5 years).

CATALYST was first established in July 2016, and its mission is “to help young people who use substance lead healthy lives through holistic, team-based care”. The team has expanded since its inception and includes several diverse specialties and experiences. Young people may be referred to the program via providers or families. During the first visit, a young person meets with a physician and a social worker for medical and mental health intakes. The team and each young person then develop an initial treatment plan, which may include scheduling with other staff (e.g., psychiatrist, recovery coach). Each week, the program team meets to review treatment plans and adjusts them as needed. Two aspects of the center that are tailored to “meet young people where they are at” include allowing the young person to decide if family is involved in the treatment plan and not requiring the young person to be abstinent to receive services.

The research team obtained data used in this study from participants’ electronic health records, including their clinical diagnoses. Demographic and patient characteristics were collected for each young person. Beginning in August 2017, patients also began completing a standardized tool to measure social determinants of health (homeless/housing insecurity, need for employment or education, difficulty paying bills, difficulty paying for medication, and food insecurity). Bagley and colleagues defined retention in care at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after their first appointment. A young person was considered retained in care if there was in-person or phone contact within the prior 30 days, but phone contact was only included if there was documentation of the program team providing on-going support. Re-engagement was defined as attending a new appointment after not being retained in care at 3, 6, 9, or 12 months. The reason for re-engagement was also collected. Young people with opioid use disorder (OUD) were also compared to those without opioid use disorder (OUD).

Of the 315 referrals from the hospital or community, 148 patients (47%) presented for a first visit. Most (79.7%) were between the ages of 18 and 27 and just over half were male (59.5%). Most were also White (60.8%), with 18.3%, 14.9%, and 1.4% identifying as Black, Hispanic, and other respectively. Although the program was reported to accept referrals for patients under 25 years of age, they accepted those up to 27 years of age during the first 30 months of the program. Almost all (93.9%) were English speaking. Slightly more than one-third (33.8%) reported currently experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

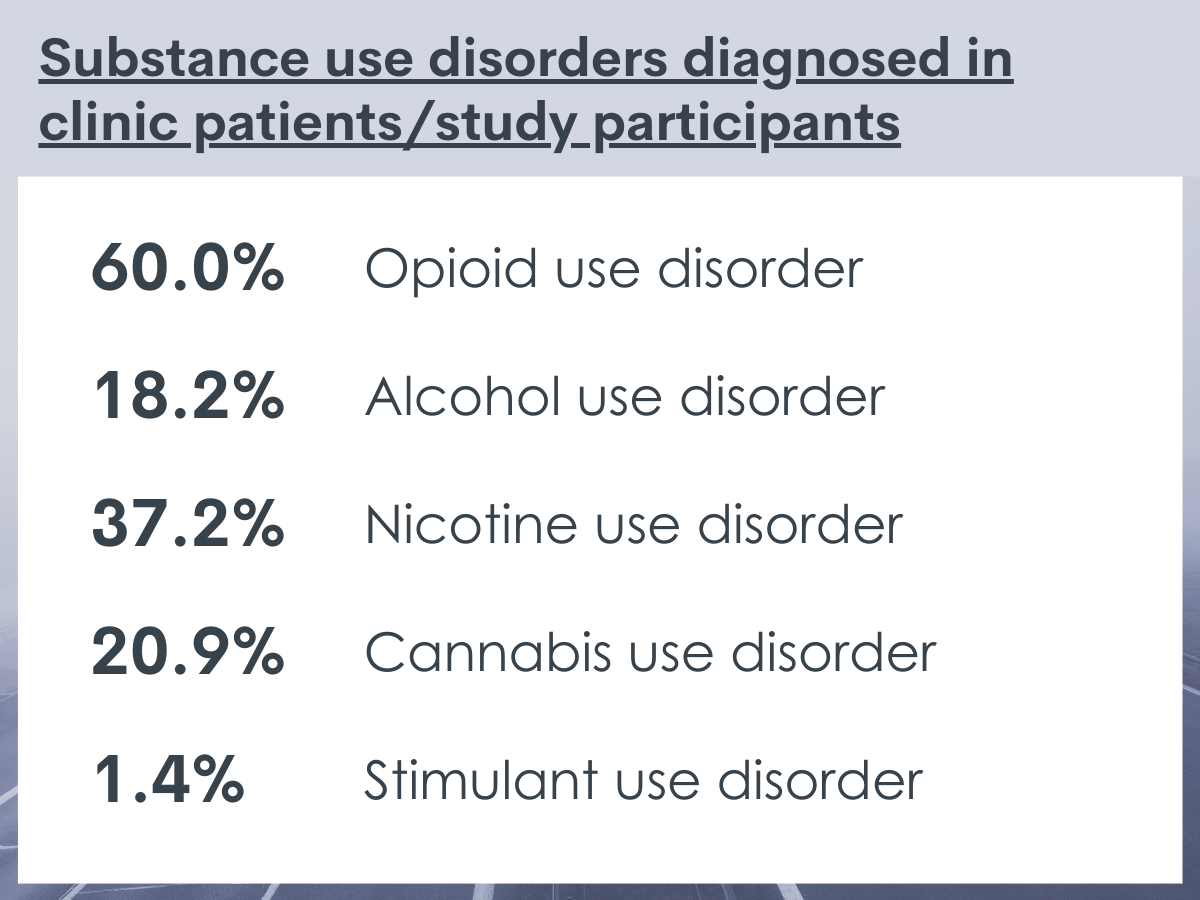

Opioid, nicotine, and cannabis were the most common substance use disorders.

Just over half of the participants (60.0%) engaged at the clinic were diagnosed with opioid use disorder. Slightly more than one-third (37.2%) had a nicotine use disorder diagnosis, and one-in-five (20.9%) had a cannabis use disorder diagnosis. Nearly one-fifth (18.2%) had an alcohol use disorder diagnosis. Almost no young people reported a stimulant use disorder. Among those with an opioid use disorder, over half (51.1%) also had a nicotine use disorder diagnosis. Almost all (90%) of the young people with an opioid use disorder were prescribed an FDA-approved medication for the condition, either buprenorphine or naltrexone.

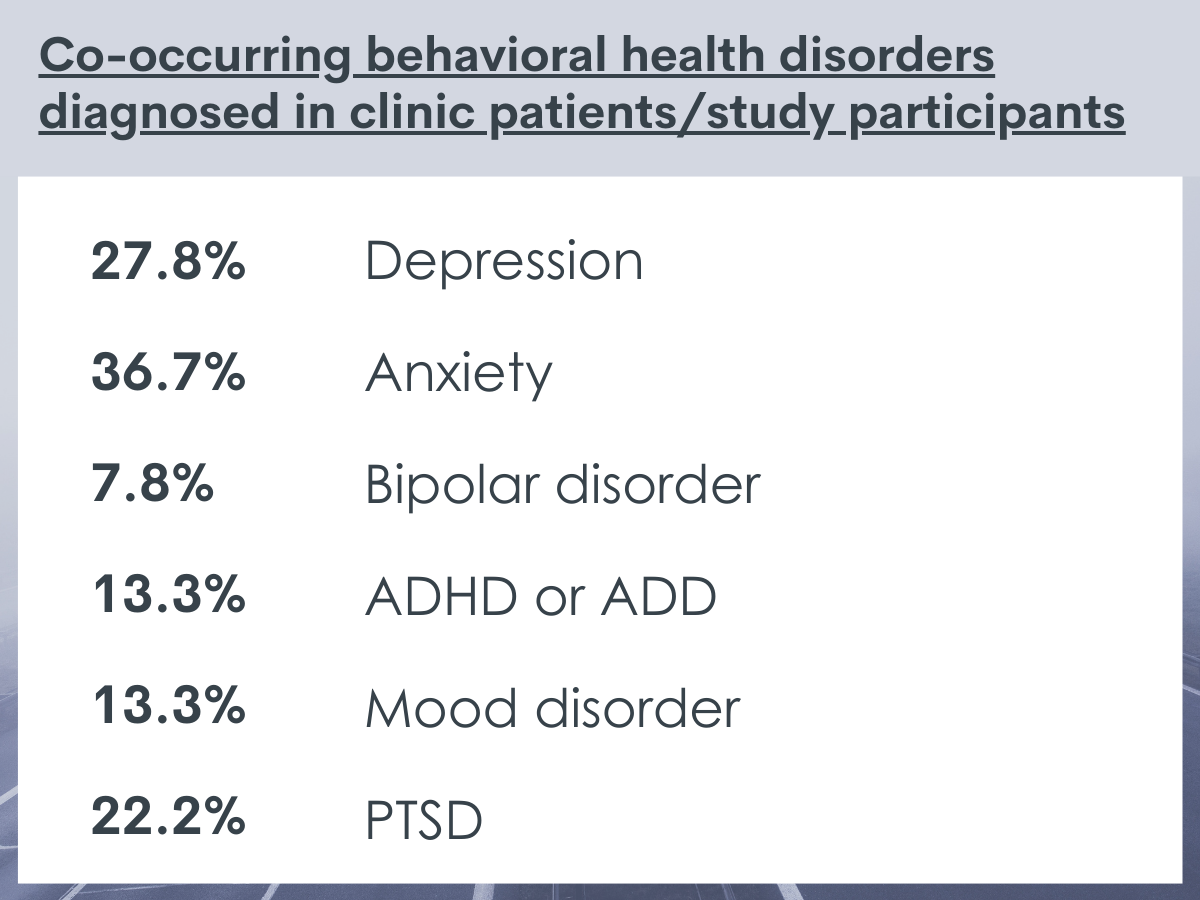

Many had additional psychosocial challenges The most common co-occurring psychiatric disorders were depressive (30%) and anxiety (32.4%) disorders. There were slight differences between those with and those without opioid use disorder.

Among the 79 (53%) of patients that completed the social determinants of health tool, 29.1% reported experiencing housing insecurity or homelessness. Similarly, 29.1% reported food insecurity. Many (24.1%) also reported being unemployed and looking for work. Several (13.9%) young people also stated difficulty getting transportation for medical appointments. A handful of young people (10% or less) cited trouble paying heating/electric bills, paying for medicine, or having trouble taking care of a child, family member, or friend.

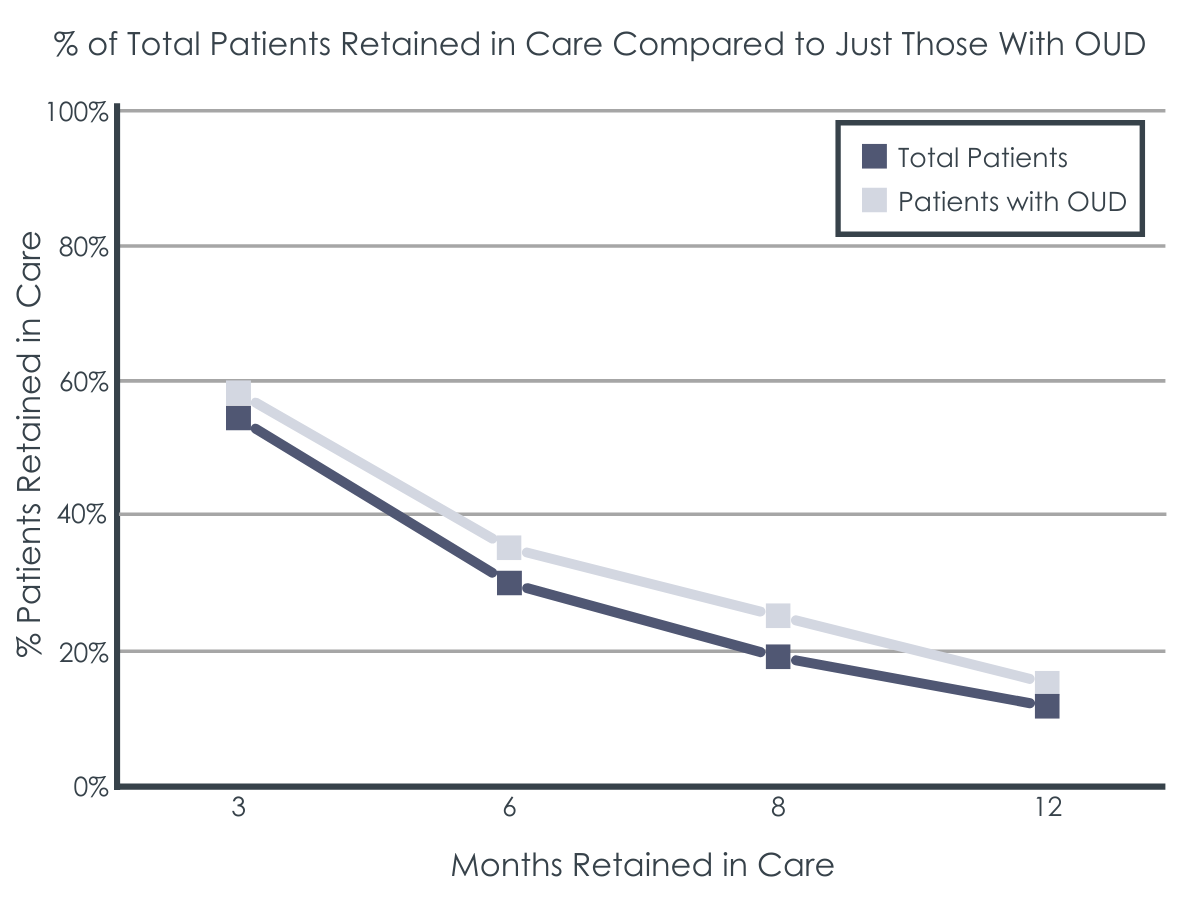

Retention dropped over the course of 3, 6, 9, and 12 months, but almost one-third re-engaged.

More than half (54.7%) of young people initially engaged were retained in care after 3 months. Among those with opioid use disorder, 58% were retained in care after 3 months. Engagement primarily consisted of in-person visits, but 20.5% to 27.8% did engaged solely via phone contact.

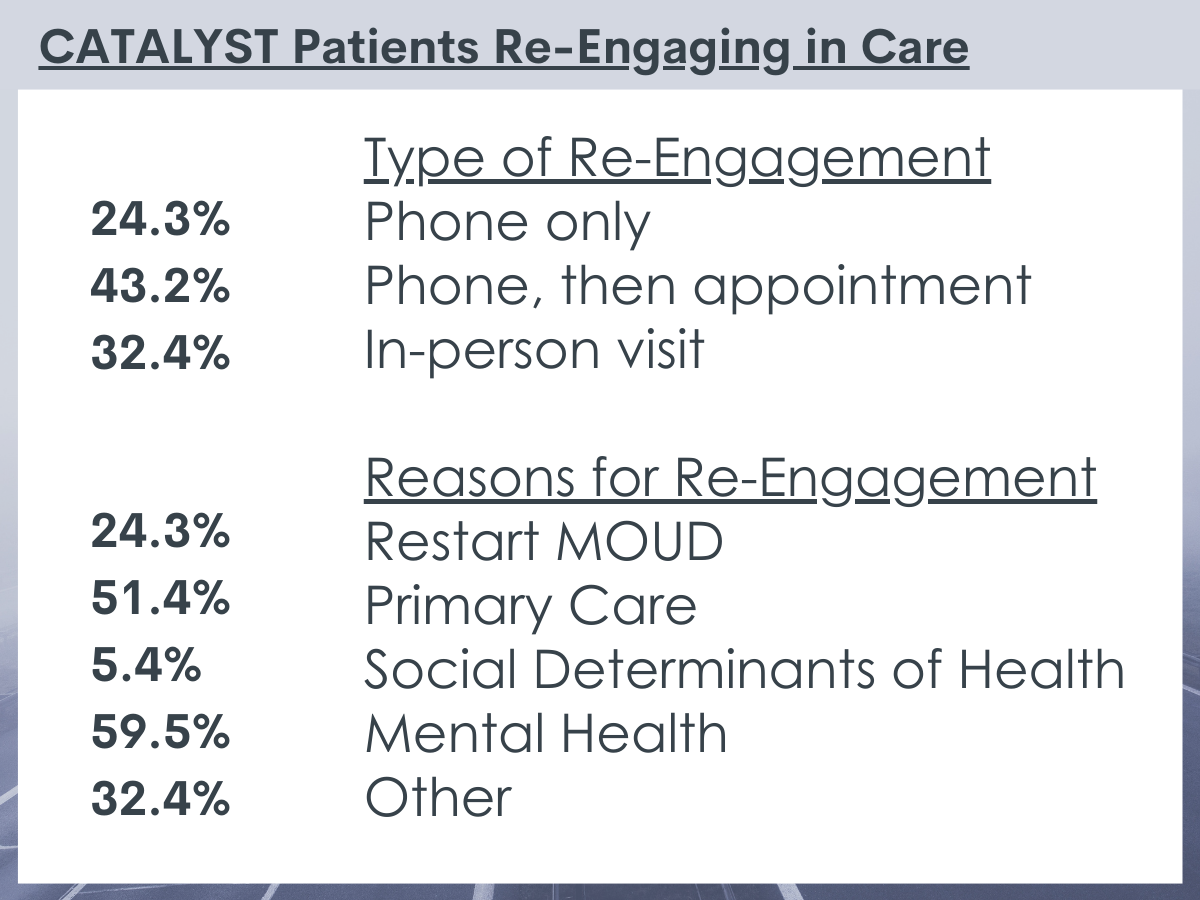

Of the 130 patients that were not retained in care at the 3-, 6-, 9-, or 12-month mark, there were 37 (28.5%) that re-engaged. Among those that re-engaged in care, the median (or middle value) time to re-engagement was 4.8 months from the last visit.

The 37 (28.5%) young people that re-engaged in care reported a variety of reasons for doing so. Over half (59.5%) re-engaged in the program to access mental health care, and over half (51.4%) reported re-engaging to access primary care services.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

In 2019, approximately 5.9 million young people aged 12 to 25 had a substance use disorder in the past year. However, only a fraction of the young people with substance use disorder receive specialized treatment as they rarely seek it out themselves. The gap between need and receipt of services, however, is compounded by the low retention and engagement rates among those that do actually access addiction services.

Connecting this population with services is important because substance use increases risk for a variety of negative health outcomes including premature mortality during these transitional years. Additionally, connecting individuals to treatment earlier is linked with shorter addiction careers. Thus, reducing potential harm over the life course.

This study describes one clinic’s solution – integrating primary care and addiction services for young people who use substances. The researchers found that young people presented for care with a variety of substance use disorders, had a high prevalence of co-occurring mental health disorders, and had unmeet social needs. Although only 1 in 10 patients were continuously retained after 12 months, almost one-third re-engaged in care. Most of the young people that re-engaged reported doing so to access mental health or primary care services. The authors, in this study, intended to describe the program and how patients fared over time. They did not compare different age groups with a substance use disorder or those who did or did not attend treatment or addiction/recovery programs outside of those integrated in primary care (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous, Smart Recovery). The researchers cannot say, based on these data, whether patients received direct benefit from the program. However, the program is a promising model that warrants further study. Creating flexible models of primary care and addiction service integration that actively pursues re-engagement, incorporates mental health services, and addresses social determinants of health may help improve the health and well-being of young people who use substances.

There are many reasons that may influence young people’s engagement, retention, and re-engagement in care including identity exploration, vulnerability to peer influences, and perceptions that substance use is normative. By integrating primary care and addiction services, providers may be more likely to identify, engage, retain, and re-engage young people who use substances. Integrated office-based care may also lower the use of more intensive acute care services, as observed in adult samples.

Flexible clinical models like this program may also improve young people’s outcomes by employing person-centered care – finding ways to engage that align with the goals and values of individual patients. Providing services without the provision of abstinence or requiring family involvement (for those 18 and older) may empower young people who use substances and facilitate on-going engagement, retention, or re-engagement. However, involving parents in the treatment process is likely to improve substance use disorder-related stress and coping for parents of youth with substance use disorders as well as youth treatment attendance. The findings from this program also strengthen the evidence base that young people who use substances often struggle with co-occurring mental health disorders and have unmeet social needs (e.g., stable housing, food security). Understanding the types of services that young people who use substances require may help with resource allocation and improve their health outcomes.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The data used in this study were not collected for research purposes, which may have resulted in the underdiagnosis of substance use and mental health disorders. Clinicians conducting initial visits might not employ the full battery of screenings for all possible substance use and mental health disorders. So, there may be individuals that meet criteria for substance use or mental health disorders but were not screened or diagnosed.

- The role of the family was not assessed. Family engagement in care may be an underlying mechanism influencing young people’s engagement, retention, and re-engagement in care.

- Health and well-being outcomes were not assessed. Thus, the researchers are unable to claim that the care provided significantly improved young people’s health or well-being (e.g., substance use, quality of life).

- Young people who use substances were not randomly assigned to the program nor was there a comparison group who did not engage with the primary care-based addiction program, which prevents claims that CATALYST directly influenced engagement, retention, or re-engagement in care compared to traditional primary and addiction services.

BOTTOM LINE

This study found that 1 in 10 young people were continuously engaged in care at CATALYST, a center that integrates primary and addiction services at a non-profit academic medical center. Also, almost 1 in 3 of those that discontinued services ultimately re-engaged, with a median time to re-engagement of 5 months. While the center aimed to provide services for any young person who uses substances, many of the young people seen at the center reported co-occurring mental health disorders, barriers to social needs (e.g., stable housing, food security), and substance use disorders. Thus, those engaged at the center may represent young people with more severe problems who would typically be seen in specialty substance use or mental health treatment. Although discontinuation of care is common among this high-risk population, developing flexible models of integrated care that address mental health needs, treat substance use disorders, tackle social determinants of health, and actively pursue re-engagement may improve engagement, retention, and re-engagement. Although the researchers in this study are unable to say whether participants received direct benefit from the program, these data do suggest that the program is a promising model to reach youth and emerging adults. Furthermore, more easily accessible services for young people who use substances, perhaps housed within primary care, may engage, retain, or reengage young people earlier in their substance use careers, which is likely to improve their substance use and other health outcomes.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study explored how primary care and addiction services may be integrated in one clinic for young people between the ages of 12-25 who use substances. They describe how such integration may increase engagement, retention, and re-engagement in care. If you or a loved one can participate in integrated services, it is unlikely to harm and it may help achieve health and wellness goals.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Integrated, office-based care for those who use substances has increased health care engagement for adults. However, there are few clinical models for young people. CATALYST at Boston Medical Center reports engagement rates consistent with traditional treatment studies and had participants re-engage in services to access mental health and primary care. Exploring and conducting more rigorous evaluation regarding how health systems could best integrate services for young people may help engage, retain, and re-engage this high-risk population.

- For scientists: This study retrospectively evaluated a clinic that integrates primary care and addiction services. The clinical model that was evaluated provides some formative evaluation data of the potential feasibility and utility of such a model for youth. The integration of services does not appear to dissuade engagement and may provide flexibility such that young people re-engage even after withdrawing from care. More work is needed, however, to establish if integrated care like that at CATALYST is likely to engage, retain, and help more youth than other traditional types of service models and provide lasting, positive recovery outcomes. Future researchers may design experimental or quasi-experimental research to compare the addiction services provided through integrated care to that of traditional treatment. Furthermore, qualitative analysis is needed to explore how youth perceive and experience integrated care. Lastly, although cost benefit analysis of adult integrated services suggests cost savings, more work is needed to establish the cost effectiveness of integrated models for young people.

- For policy makers: More research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness and feasibility of health care that integrates primary and addiction services for young people that use substances. However, this study suggests that integrated care may help maintain engagement and that a more flexible care design may encourage young people to re-engage after withdrawing from care. More comparative effectiveness data are certainly needed to determine optimal care models for this clinically challenging young population, but the integrated CATALYST model appears to be a promising start in this regard.

CITATIONS

Bagley, S. M., Hadland, S. E., Schoenberger, S. F., Gai, M. J., Topp, D., Hallett, E., Ashe, E., Samet, J. H., & Walley, A. Y. (2021). Integrating substance use care into primary care for adolescents and young adults: Lessons learned. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 129, 108376.