Putting text message post-treatment follow-up interventions to the test

Continuing care is critical for helping to prevent alcohol use disorder relapse risk following residential treatment. Modern communication technologies like text messaging can potentially improve continuing care by automating patient outreach. In this study, researchers conducted a randomized controlled trial to test a continuing care intervention that used text messages for outreach and linkage to clinicians for individuals after inpatient treatment for alcohol use disorder.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Increasingly, providers and treatment systems are recognizing that as a chronic condition, a continuum of care is best for successfully treating individuals with moderate to severe alcohol use disorder. For a variety of reasons, however, traditional continuing care options like individual and group therapy are not accessible or desirable for everyone. At the same time, research shows post-treatment recovery support like recovery management checkups, regular assessment and linkage back to treatment as needed, and brief cognitive-behavioral interventions can be effectively delivered over the telephone. The general scientific consensus is that systematic continuing care not only outperforms no continuing care and general support groups, but is also cost-effective.

Since digital technology can increase the reach of continuing care interventions, researchers are increasingly looking to its use to bridge the post-treatment continuing care gap, for instance with relapse prevention smartphone apps. A number of small scale, preliminary clinical trials also have tested text message-based continuing care models, which have shown promise. Until now however, gold-standard, large, randomized controlled trials on text message-based continuing care interventions had been lacking. Given 65% of individuals globally already communicate via text messaging, interventions like these may be more easily adoptable.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a multi-center, randomized controlled trial with 463 participants with alcohol use disorder followed for 12 months after completing 2-week, residential alcohol detoxification at one of 4 psychiatric hospitals in northern Germany. Participants were randomized to receive either, 1) text messages for 12 months asking about alcohol use and, if help was needed, with as-needed follow-up therapist phone calls, + treatment as usual, or 2) treatment as usual only.

Study outcomes:

The primary study outcome was alcohol consumption during months 10–12 after randomization with three ordered categories: heavy drinking (defined as greater than 4.3 standard drinks per day for men and 2.9 for women), non-heavy drinking, or abstinence. For participants who could not be reached for outcome assessment at the 12-month follow-up, information from collaterals such as relatives, general practitioners, and addiction counselors was sought. Patients without a final interview at the 12-month follow-up were counted as a treatment failure and included in the heavy drinking’ category, unless it was decided that available collateral follow-up information indicated something to the contrary.

Secondary study outcomes were drinking days, drinks per day, and drinks per drinking day over the 12-month study period. In addition, socio-demographic and diagnostic data were measured using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5, the Adverse Consequences from Drinking Scale, the Brief Symptom Inventory, and the Objective Social Outcomes Index.

The study sample (N= 429) was 22.7% female and on average were 45.5 years of age, and on average had drunk 12.1 drinks per day over the 12 months before study participation.

The text message intervention:

Text messages were sent automatically to the participants’ cell phone, who received up to 40 text messages during the 12 months following inpatient detoxification discharge. In months 1 and 2 participants received two texts per week, then 1 per week in month 3, and 2 texts per month during months 4 through 12.

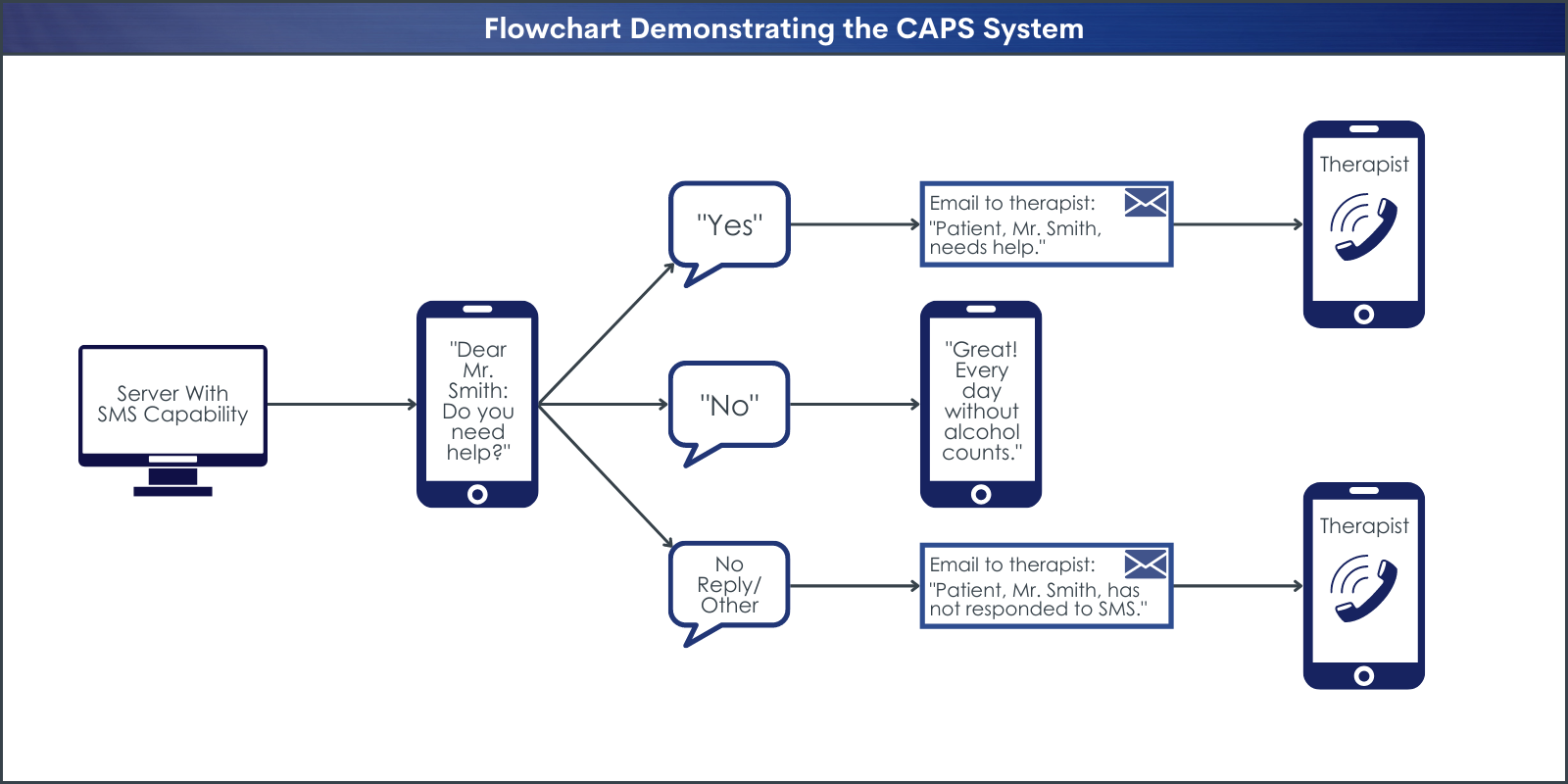

The text message consisted of a single question: “Dear Mr./Ms. … Did you drink alcohol, or do you need help? Please answer with ‘A’ for yes and ‘B’ for no”. Participants were informed that this question referred to alcohol consumption since discharge or the last text message prompt. The “Do you need help?” element could refer to any problem. All text messages were automatically sent and received by an electronic fully automatized system.

The system automatically generated emails to inform the study therapists about patient responses. Receiving an ‘A’ within 24 hours after the question having been sent triggered an automatically generated a call for help email to the therapist. After receiving this email, the study therapists called participants within 24 hours. Receiving a ‘B’ triggered an automatically generated supportive feedback text to the patient. If a participant did not answer the automatically generated question via text message within 24 hours, a ‘no reply email’ was automatically sent to the therapist, which also triggered a personal telephone call from the study therapist to the patient. The study therapists called participants back on workdays. A minimum of three attempts was made to call participant back.

Therapist telephone calls were intended to be supportive, however, no specific therapeutic approach or training was used, and therapists were free to recommend an intervention of their choice. Participants had been instructed beforehand that telephone calls would be brief. Participants were also informed that the therapist would stay in touch by watching their responses, even when no phone calls occurred.

Treatment as usual:

Treatment as usual consisted of all usual health‐care services, such as visits with general medical practitioners and psychiatrists, as needed emergency services, addiction counselling, outpatient psychotherapy, day clinic and inpatient treatment, and 3 months inpatient rehabilitation programs.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Participants in the text-message group dropped out of the study at a lower rate than those in the control group.

The proportion of participants lost from the study over the 12-month study period was higher in the treatment as usual group versus the text message + treatment as usual group (31.4% versus 22.4%).

Forty-seven participants missed their final assessment and collateral information was used to determine their outcomes (text message + treatment as usual n= 18; treatment as usual n= 29). Additionally, there were 42 participants who missed their final assessment and for whom collaterals were not available; these participants were thus classified as ‘heavy drinking’ (text message + treatment as usual n= 16, treatment as usual n= 26).

Text message follow-up group participants were moderately responsive to text messages.

Altogether, 9,019 text messages were sent to the text message group participants, who responded with 5,454 replies.

In the text message group, 22.2% of participants responded to ≥90% of the text prompts. Additionally, 42.2% of individuals in the text-message group texted an ‘A’ response indicating they had drunk or needed help at least once. Overall, these responses represented 2.7% of all responses.

A total of 1,765 phone calls took place between therapists and participants. The most frequent content was telephone counseling, occurring in 1,472 (83%) of the phone calls.

Those receiving text message follow-ups were less likely to be drinking heavily at 10-12-month follow-up.

In the text message group, 22.2% were categorized as heavy drinking (versus non-heavy drinking and abstinence) compared to 32.3% in the treatment as usual group in follow-up months 10–12, an absolute difference of 10.2%, but a relative 50% improvement over treatment as usual.

Additionally, after adjusting for sex and pre-study alcohol consumption, the text message group was 78% less likely to be drinking heavily (versus endorsing non-heavy drinking and abstinence) compared to the treatment as usual group.

Those receiving text message follow-ups had a higher rate of alcohol abstinence, but not other alcohol, health, or service utilization over 12-month follow-up.

The text message group reported more days of alcohol abstinence over the 12-month study period (on average, 267 versus 242).

However, groups were not significantly different in terms of longest abstinence period, number of reported drinking days, number of reported heavy drinking days, or drinks per drinking day.

Groups were also similar over the 12-month study period in terms of number of psychological diagnoses, self-rated health, and service utilization.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Findings in this study support previous work suggesting benefit of text message-based check-ins with as-needed phone care for individuals seeking recovery from alcohol use disorder. This is good news because it shows that meaningful improvements in treatment outcomes can be produced with a relatively uncomplicated, and low-cost intervention. Though these kinds of phone check-ins by providers can be taxing on the resources of treatment programs, these costs are well offset by the clinical benefit conferred to patients and the long-term cost savings cost to healthcare systems. The research to date suggests that initial investments in these types of regular, structured post-treatment check-ins are likely to pay for themselves over time while decreasing alcohol consumption and related harms.

Although not tested in this study, the working mechanism of text message- and phone-based continuing care is likely earlier detection of problems that may lead to relapse to active alcohol use disorder and drinking lapses that precede alcohol use disorder relapse. Timely therapeutic intervention from providers when risk is detected likely helps patients make necessary adjustments in their treatment and self-care that prevents problems from spiraling. In other words, the text messages themselves may not be of particular benefit, but rather the benefit may be that they help people stay connected with care. This idea is supported by previous findings that have showed that although monitoring alone does produce some benefit, it is monitoring plus intervention that produces the most benefit. However, it is also possible that having some accountability (i.e., knowing someone will be checking in) encourages alcohol abstinence. Most likely the benefits associated with such interventions are a combination of both factors.

Though those receiving text message follow-ups were less likely to be drinking heavily at 10-12-month follow-up and a higher rate of alcohol abstinence abstinence over the 12-month study period, notably, the researchers did not find differences between groups in terms of several other alcohol use measures, number of psychological diagnoses, self-rated health, or service utilization. This perhaps speaks to the limitations of such interventions that use text messages for outreach and brief, unstructured interventions to address any difficulties that emerge. More active, sustained interventions that link individuals to clinical and community-based supports may be needed to improve well-being over the long-term. At the same time, the capacity for such a low-cost, low-burden intervention to markedly reduce alcohol use over the first year of alcohol use disorder recovery is promising. Moreover, the fact that the findings of this large-scale, randomized controlled trial are consistent with similar findings from smaller preliminary studies adds confidence that there is real value here.

- LIMITATIONS

-

As noted by the researchers:

- The differential attrition in the arms may also have biased the results. For example, treatment as usual participants with lower consumption might have been more likely to be lost to follow-up, and individuals who did not complete follow-up were assumed to be heavy drinkers, thus biasing the treatment as usual arm towards people with heavier alcohol use. That said, the greater follow-up rates for the intervention group suggests that text message-based outreach might help keep individuals engaged with professional supports over time.

Also:

- Though not a limitation per se, this study did not explore potential relationships between lower rates of alcohol use in the text message group and engagement with care. As such, it is not known how much of the observed reductions in alcohol use was a function of the text message intervention helping participants connect with care when it was needed, and how much was a function of the texts being a drinking deterrent.

- Relatedly, the relationship between response rate to text messages and drinking outcomes was not explored. It is possible that reductions in alcohol use could be in part explained by participant motivation, such that those with greater motivation to stay sober are more likely to respond to text message check-ins and subsequently engaging with providers.

- Because the provider support phone calls were not manualized or structured, the content of the support provided to patients is not known.

BOTTOM LINE

This randomized controlled trial of a text messaging-based intervention for alcohol use disorder relapse prevention showed that text message check-ins followed by as needed provider follow-up improves 12-month post-detoxification alcohol use outcomes. This contact might help individuals stay connected to health services and actively manage relapse risks or act as a deterrent to drinking by facilitating greater awareness and accountability.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study and others like it demonstrate clear benefits associated with ongoing recovery support services after receiving an initial bout of addiction treatment. Even though not all residential treatment programs offer ongoing recovery support services like in this study, maintaining some form of clinical care (e.g., individual therapy, attending groups) and/or engaging with community-based recovery supports like mutual-help meetings and recovery community centers can have tremendous benefits in terms of helping individuals sustain addiction remission, and improve their well-being.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study and others like it demonstrate clear benefits associated with ongoing recovery support services for individuals seeking recovery from addiction. Making phone check-ins a standard part of patients’ continuing addiction care following discharge from residential treatment will likely have a positive impact on patients’ treatment outcomes over no follow-up/continuing care.

- For scientists: This study and others like it demonstrate clear benefits associated with ongoing recovery support services for individuals seeking recovery from addiction. However, more work is needed explicating both the longer-term benefits of such relapse prevention check-ins. Additionally, more work is needed to probe the mechanisms of action of such technology-based interventions.

- For policy makers: There is clear evidence supporting the benefits associated with ongoing recovery support services for individuals seeking recovery from addiction. Though such check-ins may represent a significant cost to health-care systems up front, the greater benefits to individuals, public health, and long-term cost savings are substantial. Supporting initiatives that promote continuing care for individuals in addiction recovery benefits everyone.

CITATIONS

Lucht, M., Quellmalz, A., Mende, M., Broda, A., Schmiedeknecht, A., Brosteanu, O., . . . Meyer, C. (2021). Effect of a 1-year short message service in detoxified alcohol-dependent participants: A multi-center, open-label randomized controlled trial. Addiction, 116(6), 1431-1442. DOI: 10.1111/add.15313