l

Temporary abstinence challenges are public health campaigns to reduce alcohol consumption on a public health level by encouraging a period of temporary abstinence. In a typical temporary abstinence challenge, participants abstain from alcohol use for 1 month. The first temporary abstinence challenge campaign was Dry January, a month-long voluntary alcohol abstinence campaign initiated by Alcohol Change UK in 2013.

These campaigns have grown in popularity over the past decade in part due to a growing, mainstream recognition that alcohol consumption, even at lower levels, can increase risk of serious health problems over time, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer. For example, since inception, the number of official registrants for the challenge on the Alcohol Change UK website has risen from 4,000 in 2013 to more than 175,000 in 2023.

Dry January has served as a model for a number of other, similar public health initiatives across the globe, including “Dry July” or “Febfast” in Australia, “IkPas” in the Netherlands, “Száraz November” in Hungary, and the Buddhist Lent Abstinence Campaign in Thailand. These challenges are thought to operate by temporary, large-scale shifts in drinking norms, both in terms of a temporary peer norm of abstinence (i.e., “descriptive norms”) and the degree to which they think peers might see them in a negative light if they drank alcohol (i.e., “injunctive norms”). In Belgium, the temporary abstinence challenge is called “Tournée Minérale”, meaning “mineral water round”, a play on the French phrase “Tournée Générale” (“drinks all around”). The campaign was introduced in 2017 with more than 123,000 Belgians registering to abstain from alcohol during the month of February. This study reports on changes in alcohol consumption from before the campaign to both 1 month and 6 months after the campaign and examined whether some groups had a better response to the campaign than others, over the course of the Tournée Minérale.

This was a longitudinal observational study of 8,730 people participating in a temporary abstinence challenge called Tournée Minérale Campaign in Belgium. The Tournée Minérale Campaign is a month-long temporary abstinence challenge that takes place in February. All data for the current study was collected in 2017. Participants 18 years of age or older interested in participating in the challenge could sign up on the official website.

Registrants were given an opportunity to complete 3 surveys: prior to the start of the temporary abstinence challenge, and at 1 month and 6 months after the completion of challenge. The primary outcome was drinks consumed in the past 14 days based on the Belgian standard of 10g ethanol per drink (standard drink amounts differ in different countries with the USA being 14g per standard drink).

Binge drinking was defined in this study as 4 of these standard drinks for females and 6 for males because the Belgian standard drink has less pure alcohol than the 4 for males /5 for females US standard on which this definition is based. The study also assessed attitudes towards alcohol, perceived drinking norms; perceived self-efficacy in abstaining from alcohol use, and supportive and non-supportive social influence toward drinking less. The researchers also assessed past 6-month binge drinking, defined as 4/6 drinks in the one occasion for women/men (based on the Belgian standard).

The study broke individuals into groups based on two risk rankings. One was high (11+ drinks per week) vs. low (10 or fewer drinks per week). The other was split into four groups: low risk (less than 4 drinks per week), moderate risk (4-10 drinks per week), high risk (11-17 drinks per week), and highest risk (greater than 17 drinks per week). At the 1-month post-challenge follow up, the researchers asked participants to report whether they were successful at abstaining from alcohol during the temporary abstinence challenge. The study aims were to examine (1) whether alcohol consumption changed during the course of the temporary abstinence challenge and in the 6 months that followed the challenge; and (2) if certain groups responded better to the abstinence challenge than others – for example, men vs. women and those who began the challenge with higher versus lower alcohol use.

A total of 123,842 registered for the temporary abstinence challenge and 48,349 completed the baseline survey. Of those that completed the baseline, 32.9% completed the post-challenge survey (15,610 people), and 29.5% completed the 6 month follow up survey (13,979 people). The researchers only analyzed data for participants who completed all 3 surveys (8,730). Compared to participants that only completed 1 or 2 assessments and were excluded from analyses, those completing all 3 were older, more likely to be male, higher educated, unemployed, report better general health, and not be a binge drinker. The study examined the relationship between some of these variables and alcohol use – male, lower education, and binge drinking were associated with larger decreases in alcohol use during the campaign. Given the differing directions of these effects – e.g., more males in the study may overestimate the effect while more individuals with higher education might underestimate the effect – it is unclear how these completion patterns would impact findings. While motivation for quitting or reducing drinking was not measured here, it is likely that people completing all 3 assessments were more motivated to change than those who did not. Consequently, the results below might be best understood as a characterization of changes during a temporary abstinence challenge in a best-case scenario. Of note, the primary analysis focused on examining how alcohol use changed over time regardless of participants age, gender, or educational level so they controlled for these statistically in the analyses.

Alcohol consumption declined in the full sample across the temporary abstinence challenge

Of those who completed the entire study, 89% abstained from alcohol during the monthly challenge. Alcohol consumption decreased from an average of 6.5 standard (Belgian) drinks per week at baseline to an average of 4.2 at the 1-month follow-up. Although alcohol use then increased between 1-month and 6-month follow up (5.1) this remained below the drinking level at baseline. The number of people consuming more than 3 standard alcohol drinks per week decreased from baseline (35.6%) to the post-month survey (19.7%) and the follow-up 6 months later (26.8%). The number of people reporting binge drinking also decreased from baseline (59.2%) to the 6-month follow up (43.7%).

Some groups had a stronger response to the challenge than others

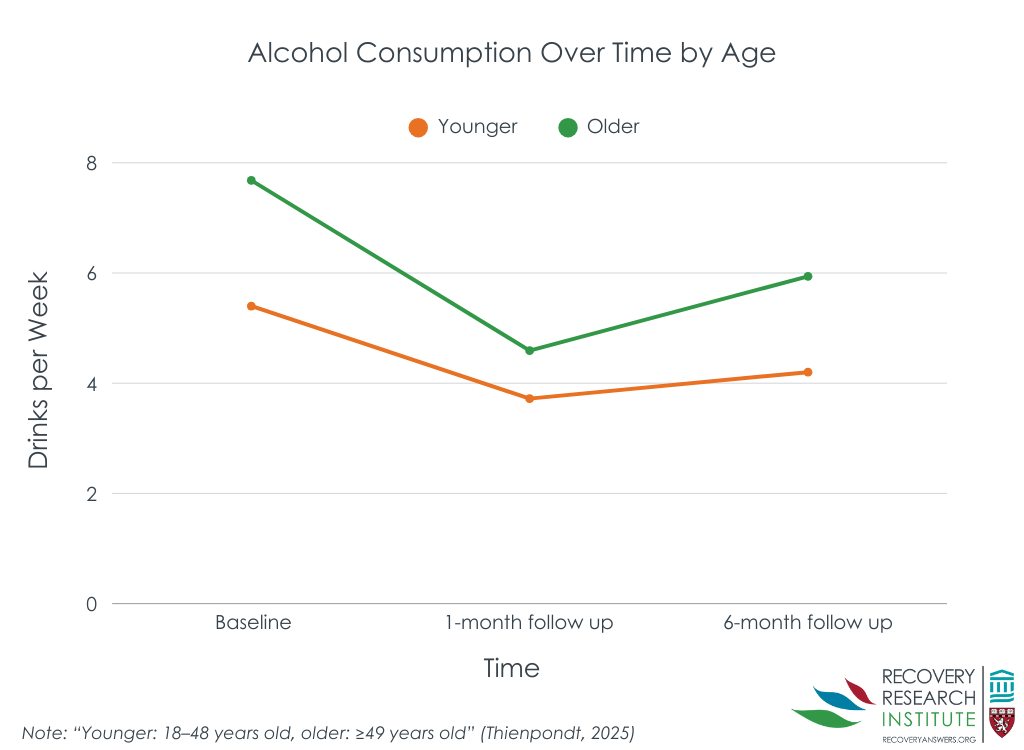

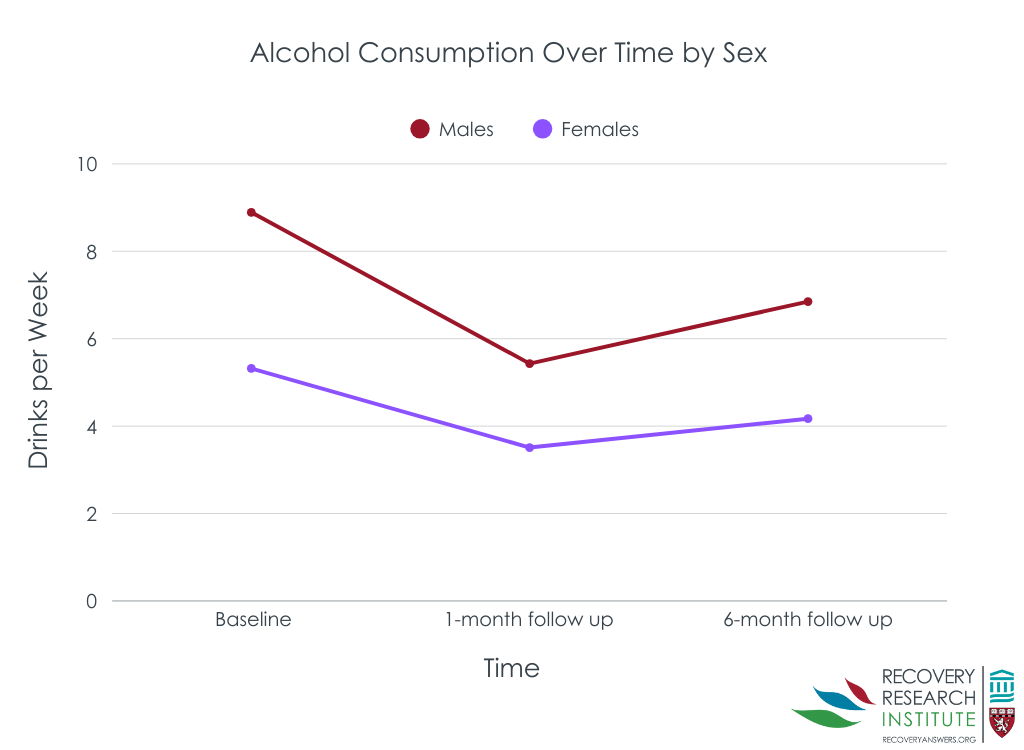

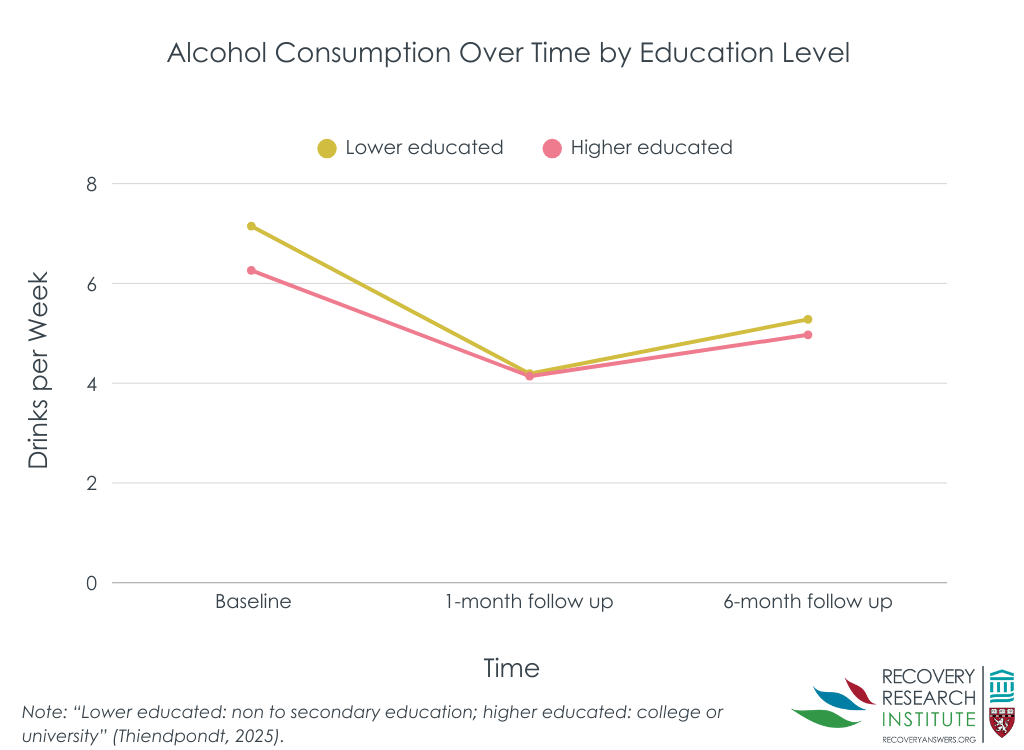

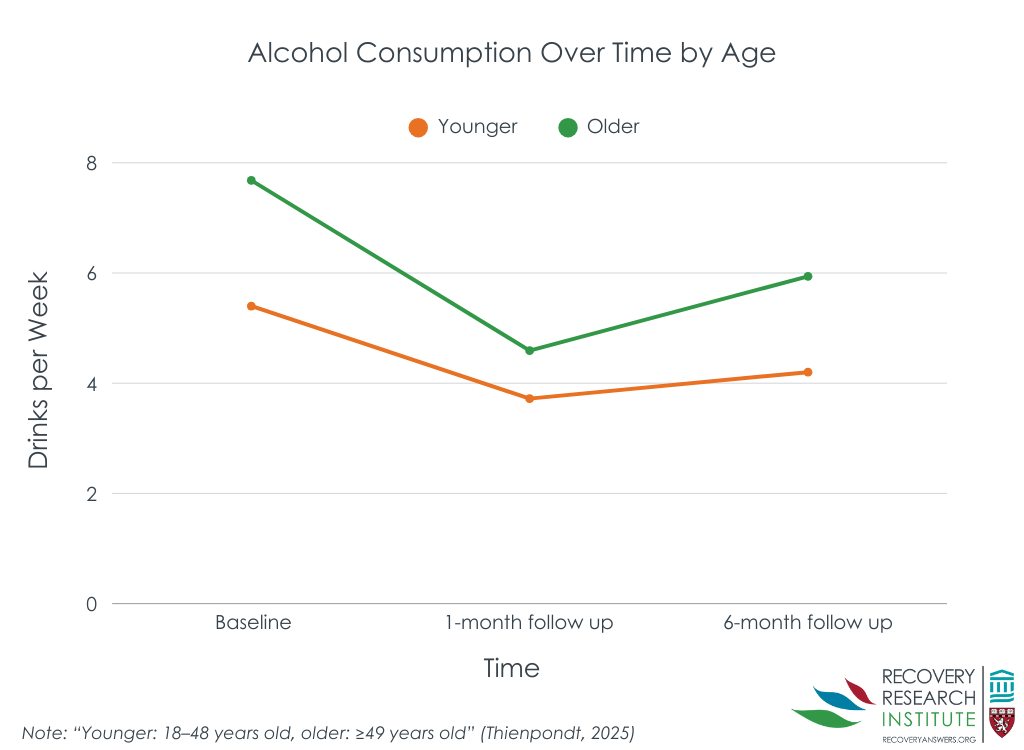

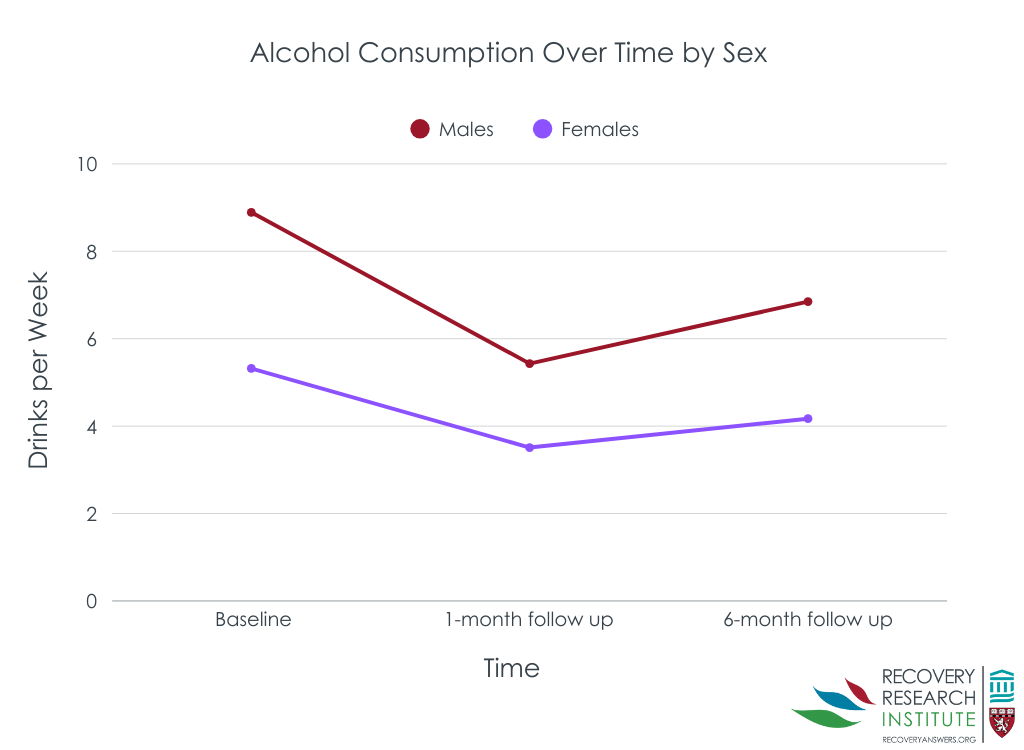

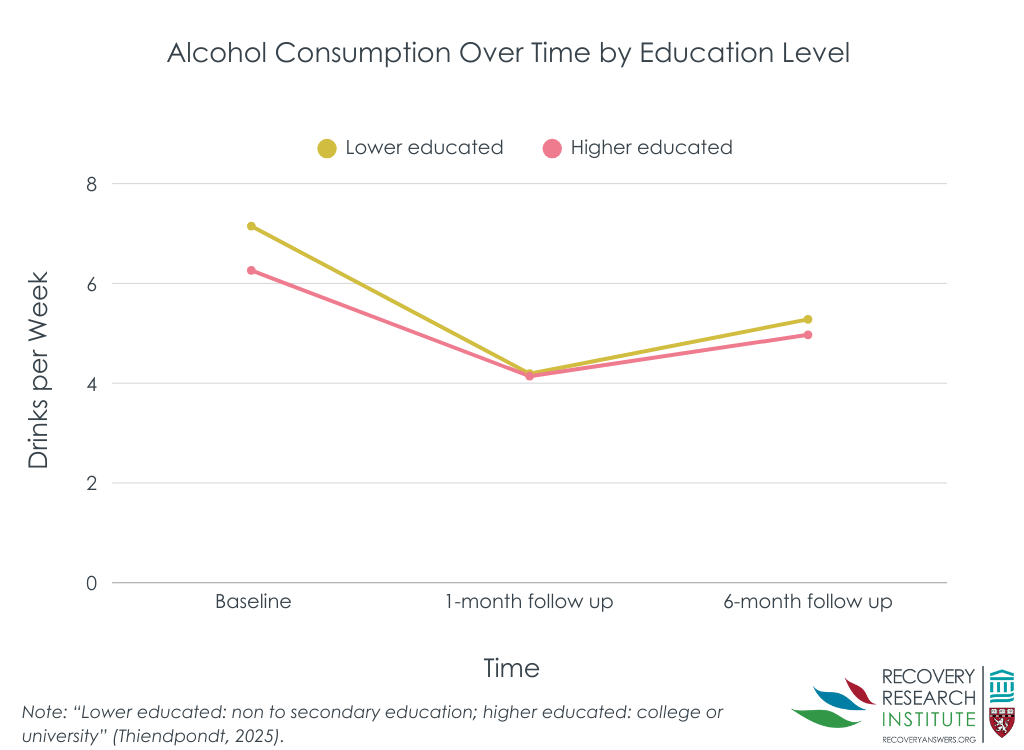

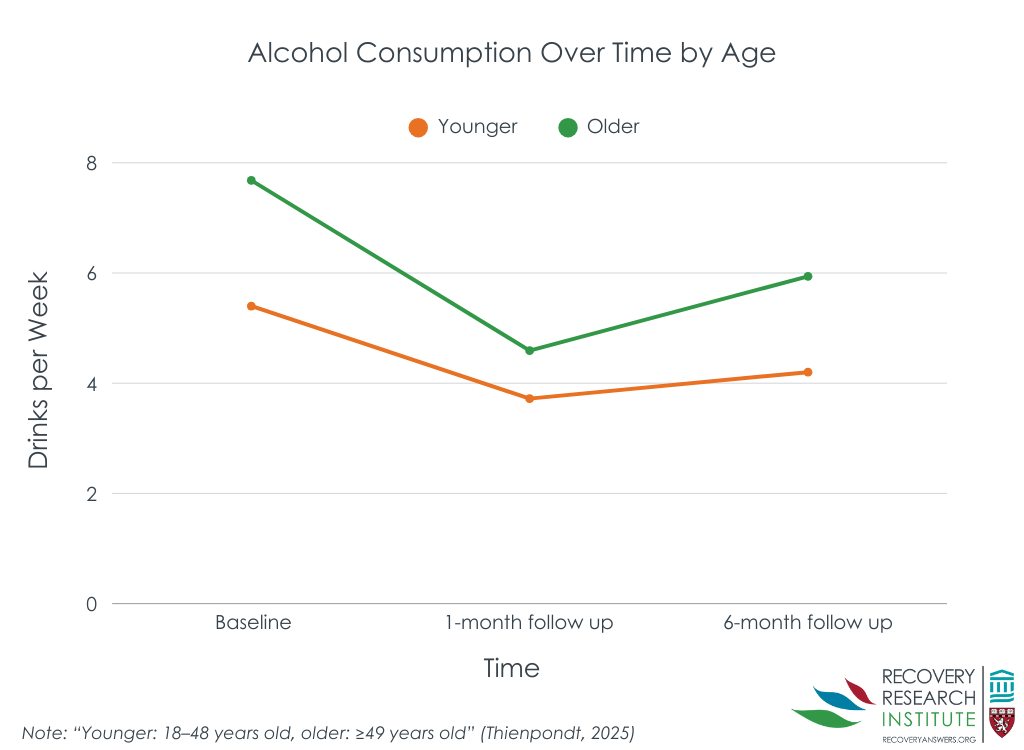

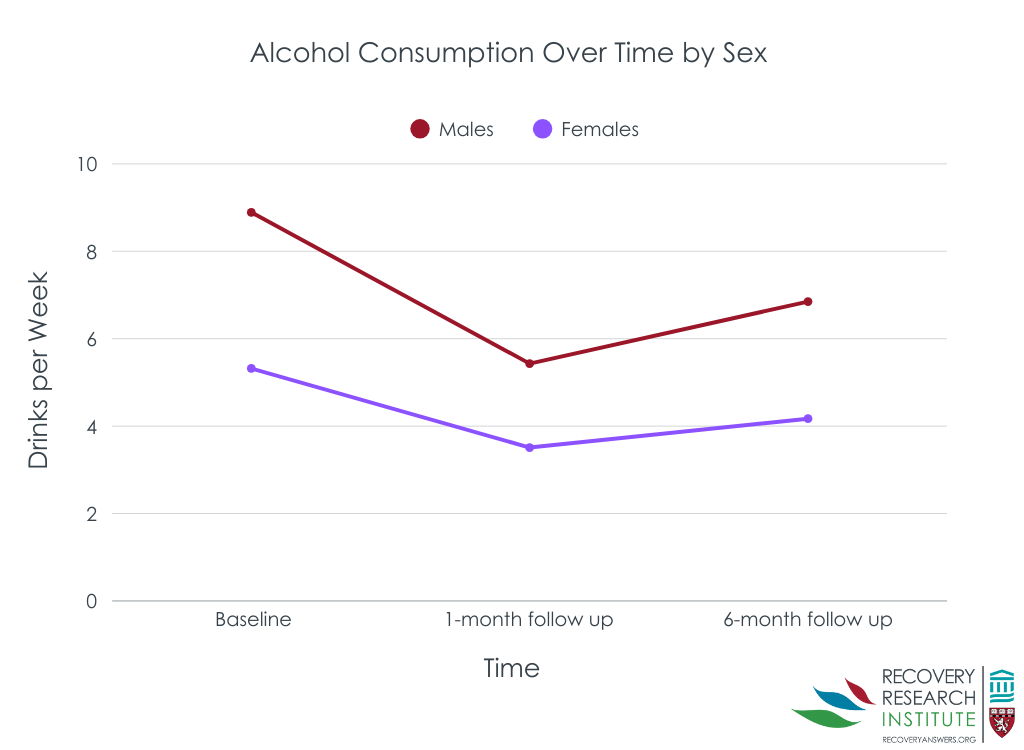

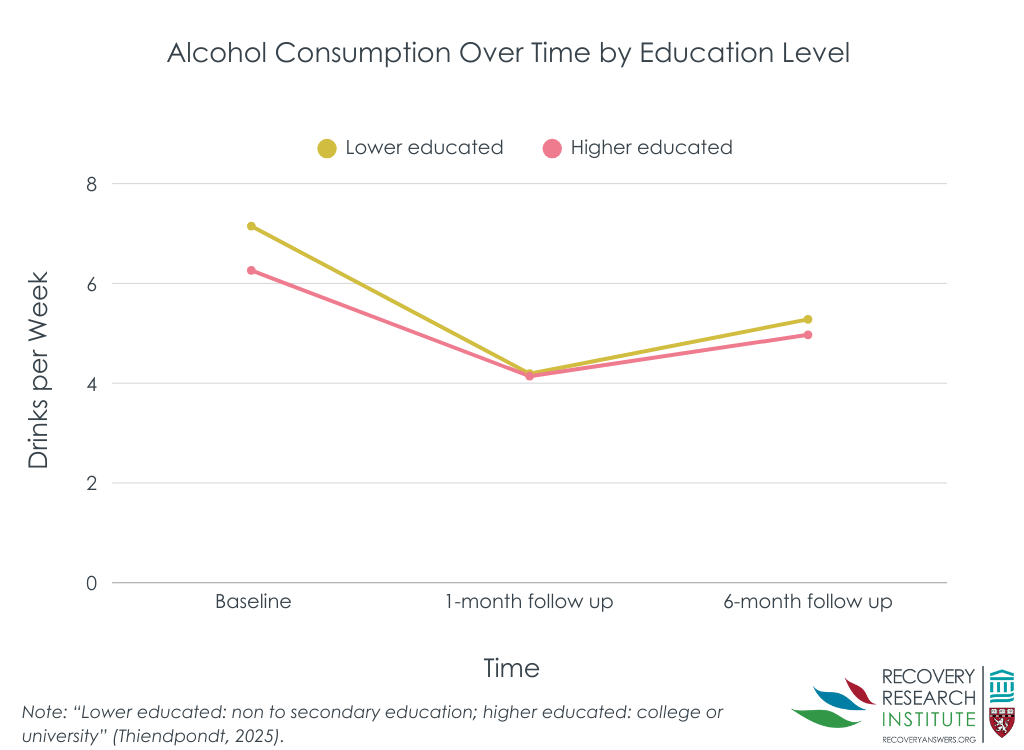

The amount of change in weekly alcohol consumption from the baseline to the 1-month follow-up depended upon the individual’s age, sex, education level, as well as their level of drinking at the start of the challenge and whether they successfully abstained during the course of the challenge. The reduction in drinking was greater among participants who were male, older, and those who had lower levels of education compared to females and those who were younger or had higher levels of education (Figure below). Further, those who successfully abstained from alcohol during the temporary abstinence challenge reported greater reductions 1 month later compared to those who did not successfully abstain from drinking.

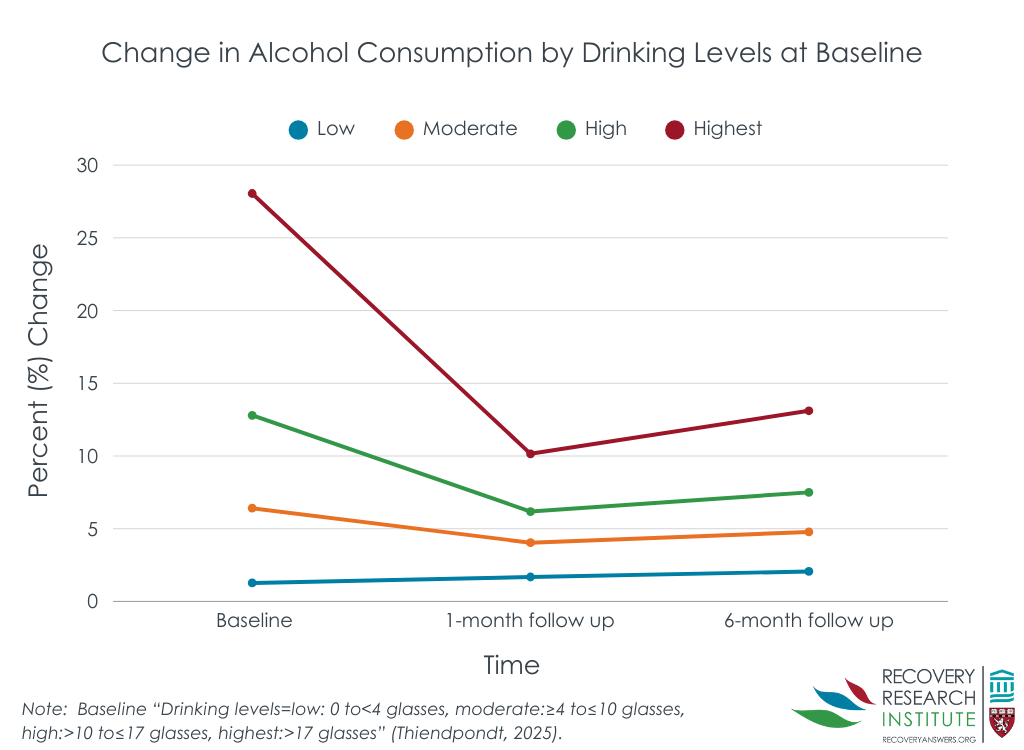

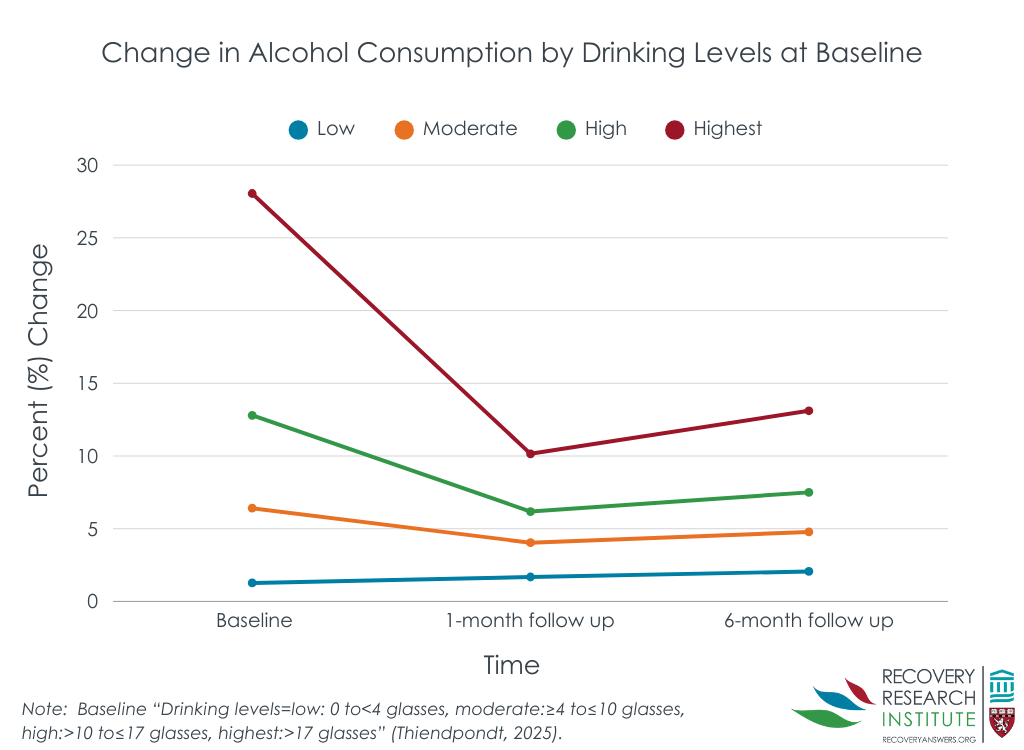

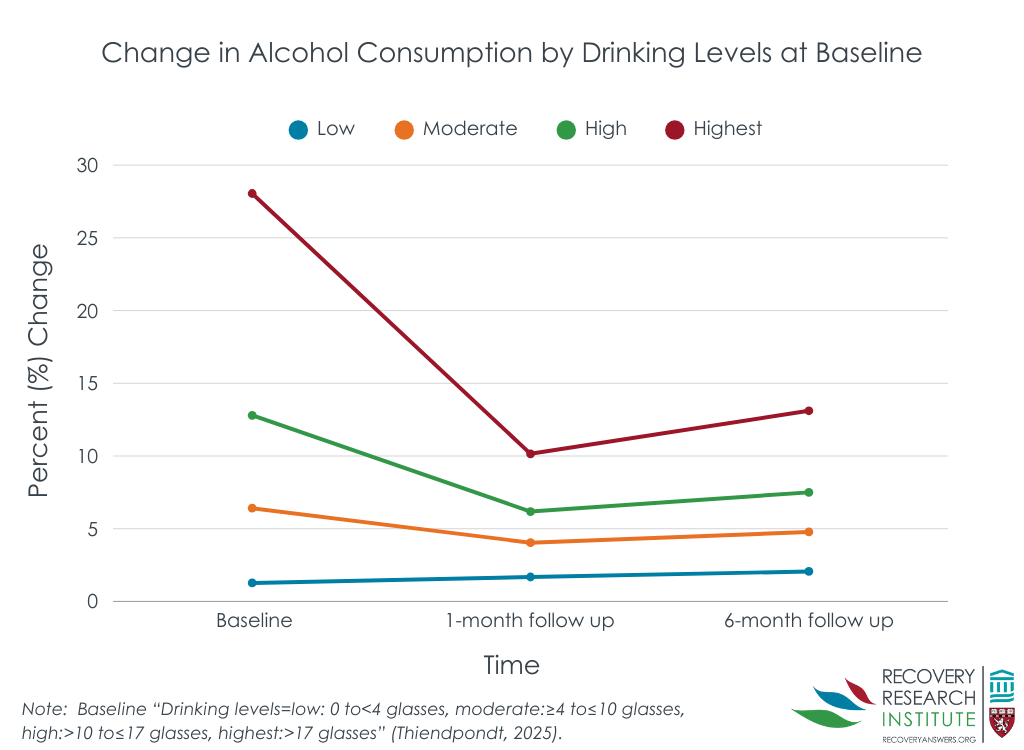

The decrease in alcohol consumption was also greater among those who reported binge drinking before the challenge and those categorized as drinking in the “high risk” range compared to those who did not binge drink and those with “lower risk”, respectively. When examining the 4-way risk groups (Figure below), in the “low risk” drinking, alcohol consumption increased slightly from baseline to the post-challenge survey, and further to the 6-month follow up survey. Those in the moderate, high, and highest risk categories decreased from baseline to post-challenge survey and increased slightly from the post-challenge survey to the 6-month survey. In all 3 cases, alcohol consumption remained below the baseline level after the 6-month follow-up, with relative declines in drinking of 25.4%, 41.4%, and 53.3% from baseline to 6-month for the moderate, high, and highest risk categories, respectively.

Common determinants of alcohol consumption also improved during the course of the study period.

Counterintuitively, positive attitudes toward alcohol increased from baseline to the 1-month and 6-month follow-ups. Perceived benefits of drinking less alcohol unexpectedly reduced from baseline to the 1-month survey but returned to the baseline level at the 6-month survey. Habit of drinking alcohol, subjective norms of drinking less, and both supportive and non-supportive social influence toward drinking less decreased from baseline to the 1-month and 6-month surveys.

Among the general population of people who drink alcohol without much consequence, motivation to stop or reduce can be low, and there are typically few if any opportunities to intervene among those who are not seeking any services or support. Temporary abstinence challenges are part of a growing “sober curious” culture across the globe that provides a social and cultural scaffolding for exploring reductions in drinking.

As a result, more and more people appear willing to temporarily give up – or at least attempt to give up – alcohol during challenges like Tournée Minérale. Even temporary reductions across a 1-month period would likely have large effects on public health at the population level including reducing toxicity and intoxication related accidents and injuries. However, the results from this study suggest that the Tournée Minérale temporary abstinence challenge is associated with a lasting reduction in alcohol use – about 1.5 drinks per week – out to 6 months, highlighting the potentially enduring influence of such a campaign. It must be remembered, however, that the sample here was a very restricted one representing a likely “best case scenario” given those who completed the surveys and were included in the study were possibly the most motivated of the bunch. Nevertheless, even for these individuals, reductions are still a good thing and lasted for up to 6 months, and such reductions may well not have happened without the stimulus of the abstinence challenge paradigm. It is important to note that, relative to deployment of different kinds of public health alcohol interventions, these campaigns appear to be highly cost effective as well.

It is important to note that participants were not randomized to complete the temporary abstinence challenge and there was no comparison group. And, as noted previously, these results only included those who completed all 3 surveys. As mentioned above, some of the factors associated with completing the entire study were predictors of better outcomes and some associated with worse outcomes – making the direction of bias unclear. That said, it is likely that those completing all 3 were more motivated to quit or reduce their drinking – an unmeasured variable – thus the reductions documented here are overall likely a best case scenario. Also, those with the highest levels of drinking had more room to improve then the other groups which may explain in part their greater decrease (i.e., “regression to the mean”).

Even so, these results are promising and highlight the opportunity that has been provided by temporary abstinence challenges. It is particularly compelling that reductions were strongest among those who, at baseline, consumed more alcohol. Although many people report benefits of drinking, costs tend to increase with the amount consumed, and individuals at higher drinking levels who choose to participate in a temporary abstinence challenge may be on the fence about their own pattern of drinking. This suggests that temporary abstinence challenges may be particularly useful campaigns for reducing consumption among those who are more likely to experience problems from drinking. This finding parallels the recommendation in the mutual-help group Moderation Management, where heavy drinking, non-addicted members obtain peer support for lower-risk drinking goals rather than abstinence, to abstain entirely for the first 30 days to reduce tolerance before embarking on their drinking goal.

Greatest decreases in alcohol consumption were among males, people who were older, and those with lower levels of education. All 3 of these populations are particularly vulnerable to drinking harms (though drinking among females has caught up to males in recent years, particularly in the United States). Aging populations will continue to grow in the next few decades due to population trends, which may strain medical systems across the globe. This study suggests that public health campaigns such as Tournée Minérale represent a low-cost opportunity to potentially reduce some of the medical harms of drinking among older adults.

Participants in this study of a temporary abstinence challenge in Belgium had drinking reductions out to 6-month follow-up, but the design does not allow us to say that the challenge was the cause of stable reductions in drinking. That said, these results are promising and temporary abstinence challenges may provide an opportunity for people to examine their own relationship with alcohol and explore their experience while not drinking.

Thienpondt, A., Van Cauwenberg, J., Van Damme, J., Nagelhout, G. E., & Deforche, B. (2025). Changes in alcohol consumption among Belgian adults participating in the internet-based one-month-abstinence campaign ‘Tournée Minérale’. Archives of Public Health, 83(29). doi: 10.1186/s13690-024-01491-2.

l

Temporary abstinence challenges are public health campaigns to reduce alcohol consumption on a public health level by encouraging a period of temporary abstinence. In a typical temporary abstinence challenge, participants abstain from alcohol use for 1 month. The first temporary abstinence challenge campaign was Dry January, a month-long voluntary alcohol abstinence campaign initiated by Alcohol Change UK in 2013.

These campaigns have grown in popularity over the past decade in part due to a growing, mainstream recognition that alcohol consumption, even at lower levels, can increase risk of serious health problems over time, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer. For example, since inception, the number of official registrants for the challenge on the Alcohol Change UK website has risen from 4,000 in 2013 to more than 175,000 in 2023.

Dry January has served as a model for a number of other, similar public health initiatives across the globe, including “Dry July” or “Febfast” in Australia, “IkPas” in the Netherlands, “Száraz November” in Hungary, and the Buddhist Lent Abstinence Campaign in Thailand. These challenges are thought to operate by temporary, large-scale shifts in drinking norms, both in terms of a temporary peer norm of abstinence (i.e., “descriptive norms”) and the degree to which they think peers might see them in a negative light if they drank alcohol (i.e., “injunctive norms”). In Belgium, the temporary abstinence challenge is called “Tournée Minérale”, meaning “mineral water round”, a play on the French phrase “Tournée Générale” (“drinks all around”). The campaign was introduced in 2017 with more than 123,000 Belgians registering to abstain from alcohol during the month of February. This study reports on changes in alcohol consumption from before the campaign to both 1 month and 6 months after the campaign and examined whether some groups had a better response to the campaign than others, over the course of the Tournée Minérale.

This was a longitudinal observational study of 8,730 people participating in a temporary abstinence challenge called Tournée Minérale Campaign in Belgium. The Tournée Minérale Campaign is a month-long temporary abstinence challenge that takes place in February. All data for the current study was collected in 2017. Participants 18 years of age or older interested in participating in the challenge could sign up on the official website.

Registrants were given an opportunity to complete 3 surveys: prior to the start of the temporary abstinence challenge, and at 1 month and 6 months after the completion of challenge. The primary outcome was drinks consumed in the past 14 days based on the Belgian standard of 10g ethanol per drink (standard drink amounts differ in different countries with the USA being 14g per standard drink).

Binge drinking was defined in this study as 4 of these standard drinks for females and 6 for males because the Belgian standard drink has less pure alcohol than the 4 for males /5 for females US standard on which this definition is based. The study also assessed attitudes towards alcohol, perceived drinking norms; perceived self-efficacy in abstaining from alcohol use, and supportive and non-supportive social influence toward drinking less. The researchers also assessed past 6-month binge drinking, defined as 4/6 drinks in the one occasion for women/men (based on the Belgian standard).

The study broke individuals into groups based on two risk rankings. One was high (11+ drinks per week) vs. low (10 or fewer drinks per week). The other was split into four groups: low risk (less than 4 drinks per week), moderate risk (4-10 drinks per week), high risk (11-17 drinks per week), and highest risk (greater than 17 drinks per week). At the 1-month post-challenge follow up, the researchers asked participants to report whether they were successful at abstaining from alcohol during the temporary abstinence challenge. The study aims were to examine (1) whether alcohol consumption changed during the course of the temporary abstinence challenge and in the 6 months that followed the challenge; and (2) if certain groups responded better to the abstinence challenge than others – for example, men vs. women and those who began the challenge with higher versus lower alcohol use.

A total of 123,842 registered for the temporary abstinence challenge and 48,349 completed the baseline survey. Of those that completed the baseline, 32.9% completed the post-challenge survey (15,610 people), and 29.5% completed the 6 month follow up survey (13,979 people). The researchers only analyzed data for participants who completed all 3 surveys (8,730). Compared to participants that only completed 1 or 2 assessments and were excluded from analyses, those completing all 3 were older, more likely to be male, higher educated, unemployed, report better general health, and not be a binge drinker. The study examined the relationship between some of these variables and alcohol use – male, lower education, and binge drinking were associated with larger decreases in alcohol use during the campaign. Given the differing directions of these effects – e.g., more males in the study may overestimate the effect while more individuals with higher education might underestimate the effect – it is unclear how these completion patterns would impact findings. While motivation for quitting or reducing drinking was not measured here, it is likely that people completing all 3 assessments were more motivated to change than those who did not. Consequently, the results below might be best understood as a characterization of changes during a temporary abstinence challenge in a best-case scenario. Of note, the primary analysis focused on examining how alcohol use changed over time regardless of participants age, gender, or educational level so they controlled for these statistically in the analyses.

Alcohol consumption declined in the full sample across the temporary abstinence challenge

Of those who completed the entire study, 89% abstained from alcohol during the monthly challenge. Alcohol consumption decreased from an average of 6.5 standard (Belgian) drinks per week at baseline to an average of 4.2 at the 1-month follow-up. Although alcohol use then increased between 1-month and 6-month follow up (5.1) this remained below the drinking level at baseline. The number of people consuming more than 3 standard alcohol drinks per week decreased from baseline (35.6%) to the post-month survey (19.7%) and the follow-up 6 months later (26.8%). The number of people reporting binge drinking also decreased from baseline (59.2%) to the 6-month follow up (43.7%).

Some groups had a stronger response to the challenge than others

The amount of change in weekly alcohol consumption from the baseline to the 1-month follow-up depended upon the individual’s age, sex, education level, as well as their level of drinking at the start of the challenge and whether they successfully abstained during the course of the challenge. The reduction in drinking was greater among participants who were male, older, and those who had lower levels of education compared to females and those who were younger or had higher levels of education (Figure below). Further, those who successfully abstained from alcohol during the temporary abstinence challenge reported greater reductions 1 month later compared to those who did not successfully abstain from drinking.

The decrease in alcohol consumption was also greater among those who reported binge drinking before the challenge and those categorized as drinking in the “high risk” range compared to those who did not binge drink and those with “lower risk”, respectively. When examining the 4-way risk groups (Figure below), in the “low risk” drinking, alcohol consumption increased slightly from baseline to the post-challenge survey, and further to the 6-month follow up survey. Those in the moderate, high, and highest risk categories decreased from baseline to post-challenge survey and increased slightly from the post-challenge survey to the 6-month survey. In all 3 cases, alcohol consumption remained below the baseline level after the 6-month follow-up, with relative declines in drinking of 25.4%, 41.4%, and 53.3% from baseline to 6-month for the moderate, high, and highest risk categories, respectively.

Common determinants of alcohol consumption also improved during the course of the study period.

Counterintuitively, positive attitudes toward alcohol increased from baseline to the 1-month and 6-month follow-ups. Perceived benefits of drinking less alcohol unexpectedly reduced from baseline to the 1-month survey but returned to the baseline level at the 6-month survey. Habit of drinking alcohol, subjective norms of drinking less, and both supportive and non-supportive social influence toward drinking less decreased from baseline to the 1-month and 6-month surveys.

Among the general population of people who drink alcohol without much consequence, motivation to stop or reduce can be low, and there are typically few if any opportunities to intervene among those who are not seeking any services or support. Temporary abstinence challenges are part of a growing “sober curious” culture across the globe that provides a social and cultural scaffolding for exploring reductions in drinking.

As a result, more and more people appear willing to temporarily give up – or at least attempt to give up – alcohol during challenges like Tournée Minérale. Even temporary reductions across a 1-month period would likely have large effects on public health at the population level including reducing toxicity and intoxication related accidents and injuries. However, the results from this study suggest that the Tournée Minérale temporary abstinence challenge is associated with a lasting reduction in alcohol use – about 1.5 drinks per week – out to 6 months, highlighting the potentially enduring influence of such a campaign. It must be remembered, however, that the sample here was a very restricted one representing a likely “best case scenario” given those who completed the surveys and were included in the study were possibly the most motivated of the bunch. Nevertheless, even for these individuals, reductions are still a good thing and lasted for up to 6 months, and such reductions may well not have happened without the stimulus of the abstinence challenge paradigm. It is important to note that, relative to deployment of different kinds of public health alcohol interventions, these campaigns appear to be highly cost effective as well.

It is important to note that participants were not randomized to complete the temporary abstinence challenge and there was no comparison group. And, as noted previously, these results only included those who completed all 3 surveys. As mentioned above, some of the factors associated with completing the entire study were predictors of better outcomes and some associated with worse outcomes – making the direction of bias unclear. That said, it is likely that those completing all 3 were more motivated to quit or reduce their drinking – an unmeasured variable – thus the reductions documented here are overall likely a best case scenario. Also, those with the highest levels of drinking had more room to improve then the other groups which may explain in part their greater decrease (i.e., “regression to the mean”).

Even so, these results are promising and highlight the opportunity that has been provided by temporary abstinence challenges. It is particularly compelling that reductions were strongest among those who, at baseline, consumed more alcohol. Although many people report benefits of drinking, costs tend to increase with the amount consumed, and individuals at higher drinking levels who choose to participate in a temporary abstinence challenge may be on the fence about their own pattern of drinking. This suggests that temporary abstinence challenges may be particularly useful campaigns for reducing consumption among those who are more likely to experience problems from drinking. This finding parallels the recommendation in the mutual-help group Moderation Management, where heavy drinking, non-addicted members obtain peer support for lower-risk drinking goals rather than abstinence, to abstain entirely for the first 30 days to reduce tolerance before embarking on their drinking goal.

Greatest decreases in alcohol consumption were among males, people who were older, and those with lower levels of education. All 3 of these populations are particularly vulnerable to drinking harms (though drinking among females has caught up to males in recent years, particularly in the United States). Aging populations will continue to grow in the next few decades due to population trends, which may strain medical systems across the globe. This study suggests that public health campaigns such as Tournée Minérale represent a low-cost opportunity to potentially reduce some of the medical harms of drinking among older adults.

Participants in this study of a temporary abstinence challenge in Belgium had drinking reductions out to 6-month follow-up, but the design does not allow us to say that the challenge was the cause of stable reductions in drinking. That said, these results are promising and temporary abstinence challenges may provide an opportunity for people to examine their own relationship with alcohol and explore their experience while not drinking.

Thienpondt, A., Van Cauwenberg, J., Van Damme, J., Nagelhout, G. E., & Deforche, B. (2025). Changes in alcohol consumption among Belgian adults participating in the internet-based one-month-abstinence campaign ‘Tournée Minérale’. Archives of Public Health, 83(29). doi: 10.1186/s13690-024-01491-2.

l

Temporary abstinence challenges are public health campaigns to reduce alcohol consumption on a public health level by encouraging a period of temporary abstinence. In a typical temporary abstinence challenge, participants abstain from alcohol use for 1 month. The first temporary abstinence challenge campaign was Dry January, a month-long voluntary alcohol abstinence campaign initiated by Alcohol Change UK in 2013.

These campaigns have grown in popularity over the past decade in part due to a growing, mainstream recognition that alcohol consumption, even at lower levels, can increase risk of serious health problems over time, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer. For example, since inception, the number of official registrants for the challenge on the Alcohol Change UK website has risen from 4,000 in 2013 to more than 175,000 in 2023.

Dry January has served as a model for a number of other, similar public health initiatives across the globe, including “Dry July” or “Febfast” in Australia, “IkPas” in the Netherlands, “Száraz November” in Hungary, and the Buddhist Lent Abstinence Campaign in Thailand. These challenges are thought to operate by temporary, large-scale shifts in drinking norms, both in terms of a temporary peer norm of abstinence (i.e., “descriptive norms”) and the degree to which they think peers might see them in a negative light if they drank alcohol (i.e., “injunctive norms”). In Belgium, the temporary abstinence challenge is called “Tournée Minérale”, meaning “mineral water round”, a play on the French phrase “Tournée Générale” (“drinks all around”). The campaign was introduced in 2017 with more than 123,000 Belgians registering to abstain from alcohol during the month of February. This study reports on changes in alcohol consumption from before the campaign to both 1 month and 6 months after the campaign and examined whether some groups had a better response to the campaign than others, over the course of the Tournée Minérale.

This was a longitudinal observational study of 8,730 people participating in a temporary abstinence challenge called Tournée Minérale Campaign in Belgium. The Tournée Minérale Campaign is a month-long temporary abstinence challenge that takes place in February. All data for the current study was collected in 2017. Participants 18 years of age or older interested in participating in the challenge could sign up on the official website.

Registrants were given an opportunity to complete 3 surveys: prior to the start of the temporary abstinence challenge, and at 1 month and 6 months after the completion of challenge. The primary outcome was drinks consumed in the past 14 days based on the Belgian standard of 10g ethanol per drink (standard drink amounts differ in different countries with the USA being 14g per standard drink).

Binge drinking was defined in this study as 4 of these standard drinks for females and 6 for males because the Belgian standard drink has less pure alcohol than the 4 for males /5 for females US standard on which this definition is based. The study also assessed attitudes towards alcohol, perceived drinking norms; perceived self-efficacy in abstaining from alcohol use, and supportive and non-supportive social influence toward drinking less. The researchers also assessed past 6-month binge drinking, defined as 4/6 drinks in the one occasion for women/men (based on the Belgian standard).

The study broke individuals into groups based on two risk rankings. One was high (11+ drinks per week) vs. low (10 or fewer drinks per week). The other was split into four groups: low risk (less than 4 drinks per week), moderate risk (4-10 drinks per week), high risk (11-17 drinks per week), and highest risk (greater than 17 drinks per week). At the 1-month post-challenge follow up, the researchers asked participants to report whether they were successful at abstaining from alcohol during the temporary abstinence challenge. The study aims were to examine (1) whether alcohol consumption changed during the course of the temporary abstinence challenge and in the 6 months that followed the challenge; and (2) if certain groups responded better to the abstinence challenge than others – for example, men vs. women and those who began the challenge with higher versus lower alcohol use.

A total of 123,842 registered for the temporary abstinence challenge and 48,349 completed the baseline survey. Of those that completed the baseline, 32.9% completed the post-challenge survey (15,610 people), and 29.5% completed the 6 month follow up survey (13,979 people). The researchers only analyzed data for participants who completed all 3 surveys (8,730). Compared to participants that only completed 1 or 2 assessments and were excluded from analyses, those completing all 3 were older, more likely to be male, higher educated, unemployed, report better general health, and not be a binge drinker. The study examined the relationship between some of these variables and alcohol use – male, lower education, and binge drinking were associated with larger decreases in alcohol use during the campaign. Given the differing directions of these effects – e.g., more males in the study may overestimate the effect while more individuals with higher education might underestimate the effect – it is unclear how these completion patterns would impact findings. While motivation for quitting or reducing drinking was not measured here, it is likely that people completing all 3 assessments were more motivated to change than those who did not. Consequently, the results below might be best understood as a characterization of changes during a temporary abstinence challenge in a best-case scenario. Of note, the primary analysis focused on examining how alcohol use changed over time regardless of participants age, gender, or educational level so they controlled for these statistically in the analyses.

Alcohol consumption declined in the full sample across the temporary abstinence challenge

Of those who completed the entire study, 89% abstained from alcohol during the monthly challenge. Alcohol consumption decreased from an average of 6.5 standard (Belgian) drinks per week at baseline to an average of 4.2 at the 1-month follow-up. Although alcohol use then increased between 1-month and 6-month follow up (5.1) this remained below the drinking level at baseline. The number of people consuming more than 3 standard alcohol drinks per week decreased from baseline (35.6%) to the post-month survey (19.7%) and the follow-up 6 months later (26.8%). The number of people reporting binge drinking also decreased from baseline (59.2%) to the 6-month follow up (43.7%).

Some groups had a stronger response to the challenge than others

The amount of change in weekly alcohol consumption from the baseline to the 1-month follow-up depended upon the individual’s age, sex, education level, as well as their level of drinking at the start of the challenge and whether they successfully abstained during the course of the challenge. The reduction in drinking was greater among participants who were male, older, and those who had lower levels of education compared to females and those who were younger or had higher levels of education (Figure below). Further, those who successfully abstained from alcohol during the temporary abstinence challenge reported greater reductions 1 month later compared to those who did not successfully abstain from drinking.

The decrease in alcohol consumption was also greater among those who reported binge drinking before the challenge and those categorized as drinking in the “high risk” range compared to those who did not binge drink and those with “lower risk”, respectively. When examining the 4-way risk groups (Figure below), in the “low risk” drinking, alcohol consumption increased slightly from baseline to the post-challenge survey, and further to the 6-month follow up survey. Those in the moderate, high, and highest risk categories decreased from baseline to post-challenge survey and increased slightly from the post-challenge survey to the 6-month survey. In all 3 cases, alcohol consumption remained below the baseline level after the 6-month follow-up, with relative declines in drinking of 25.4%, 41.4%, and 53.3% from baseline to 6-month for the moderate, high, and highest risk categories, respectively.

Common determinants of alcohol consumption also improved during the course of the study period.

Counterintuitively, positive attitudes toward alcohol increased from baseline to the 1-month and 6-month follow-ups. Perceived benefits of drinking less alcohol unexpectedly reduced from baseline to the 1-month survey but returned to the baseline level at the 6-month survey. Habit of drinking alcohol, subjective norms of drinking less, and both supportive and non-supportive social influence toward drinking less decreased from baseline to the 1-month and 6-month surveys.

Among the general population of people who drink alcohol without much consequence, motivation to stop or reduce can be low, and there are typically few if any opportunities to intervene among those who are not seeking any services or support. Temporary abstinence challenges are part of a growing “sober curious” culture across the globe that provides a social and cultural scaffolding for exploring reductions in drinking.

As a result, more and more people appear willing to temporarily give up – or at least attempt to give up – alcohol during challenges like Tournée Minérale. Even temporary reductions across a 1-month period would likely have large effects on public health at the population level including reducing toxicity and intoxication related accidents and injuries. However, the results from this study suggest that the Tournée Minérale temporary abstinence challenge is associated with a lasting reduction in alcohol use – about 1.5 drinks per week – out to 6 months, highlighting the potentially enduring influence of such a campaign. It must be remembered, however, that the sample here was a very restricted one representing a likely “best case scenario” given those who completed the surveys and were included in the study were possibly the most motivated of the bunch. Nevertheless, even for these individuals, reductions are still a good thing and lasted for up to 6 months, and such reductions may well not have happened without the stimulus of the abstinence challenge paradigm. It is important to note that, relative to deployment of different kinds of public health alcohol interventions, these campaigns appear to be highly cost effective as well.

It is important to note that participants were not randomized to complete the temporary abstinence challenge and there was no comparison group. And, as noted previously, these results only included those who completed all 3 surveys. As mentioned above, some of the factors associated with completing the entire study were predictors of better outcomes and some associated with worse outcomes – making the direction of bias unclear. That said, it is likely that those completing all 3 were more motivated to quit or reduce their drinking – an unmeasured variable – thus the reductions documented here are overall likely a best case scenario. Also, those with the highest levels of drinking had more room to improve then the other groups which may explain in part their greater decrease (i.e., “regression to the mean”).

Even so, these results are promising and highlight the opportunity that has been provided by temporary abstinence challenges. It is particularly compelling that reductions were strongest among those who, at baseline, consumed more alcohol. Although many people report benefits of drinking, costs tend to increase with the amount consumed, and individuals at higher drinking levels who choose to participate in a temporary abstinence challenge may be on the fence about their own pattern of drinking. This suggests that temporary abstinence challenges may be particularly useful campaigns for reducing consumption among those who are more likely to experience problems from drinking. This finding parallels the recommendation in the mutual-help group Moderation Management, where heavy drinking, non-addicted members obtain peer support for lower-risk drinking goals rather than abstinence, to abstain entirely for the first 30 days to reduce tolerance before embarking on their drinking goal.

Greatest decreases in alcohol consumption were among males, people who were older, and those with lower levels of education. All 3 of these populations are particularly vulnerable to drinking harms (though drinking among females has caught up to males in recent years, particularly in the United States). Aging populations will continue to grow in the next few decades due to population trends, which may strain medical systems across the globe. This study suggests that public health campaigns such as Tournée Minérale represent a low-cost opportunity to potentially reduce some of the medical harms of drinking among older adults.

Participants in this study of a temporary abstinence challenge in Belgium had drinking reductions out to 6-month follow-up, but the design does not allow us to say that the challenge was the cause of stable reductions in drinking. That said, these results are promising and temporary abstinence challenges may provide an opportunity for people to examine their own relationship with alcohol and explore their experience while not drinking.

Thienpondt, A., Van Cauwenberg, J., Van Damme, J., Nagelhout, G. E., & Deforche, B. (2025). Changes in alcohol consumption among Belgian adults participating in the internet-based one-month-abstinence campaign ‘Tournée Minérale’. Archives of Public Health, 83(29). doi: 10.1186/s13690-024-01491-2.

151 Merrimac St., 4th Floor. Boston, MA 02114