l

People may internalize negative attitudes and stereotypes about groups to which they belong in a process dubbed “self-stigma”. For example, people who engage in problematic alcohol use may come to recognize symptoms of their disorder they are experiencing as a personal failing. Such internalizing of stigma can lead to feelings of shame and reduced self-esteem which can lead to a ´why try´ effect: an individual’s self-worth is lowered so much that they no longer pursue personal goals (e.g., career milestones) and/or abandon self-care practices (e.g., pursuing medical treatment). Fear of stigma among people with alcohol use disorder can be especially pernicious as it could impact treatment outcomes.

Evidence suggests some patients may avoid substance use disorder treatment out of fear of stigmatization. Furthermore, self-stigma is associated with lower perceived ability to abstain from alcohol use in the future among patients undergoing alcohol use disorder treatment. Assessing self-stigma among patients in clinical settings could identify those who may benefit from alcohol use disorder treatment but who avoid care. However current measures of self-stigma are long and challenging to implement. The Self-Stigma in Alcohol Dependence Scale is 64 items long which may not be feasible to use clinical settings. There is a need for briefer scales which can be used in real world healthcare and recovery support service settings, as well as in research contexts where participant time burden is often an issue. To this end, this study tested and validated a shortened version of the Self-Stigma in Alcohol Dependence Scale and examined relevant factors associated with self-stigma.

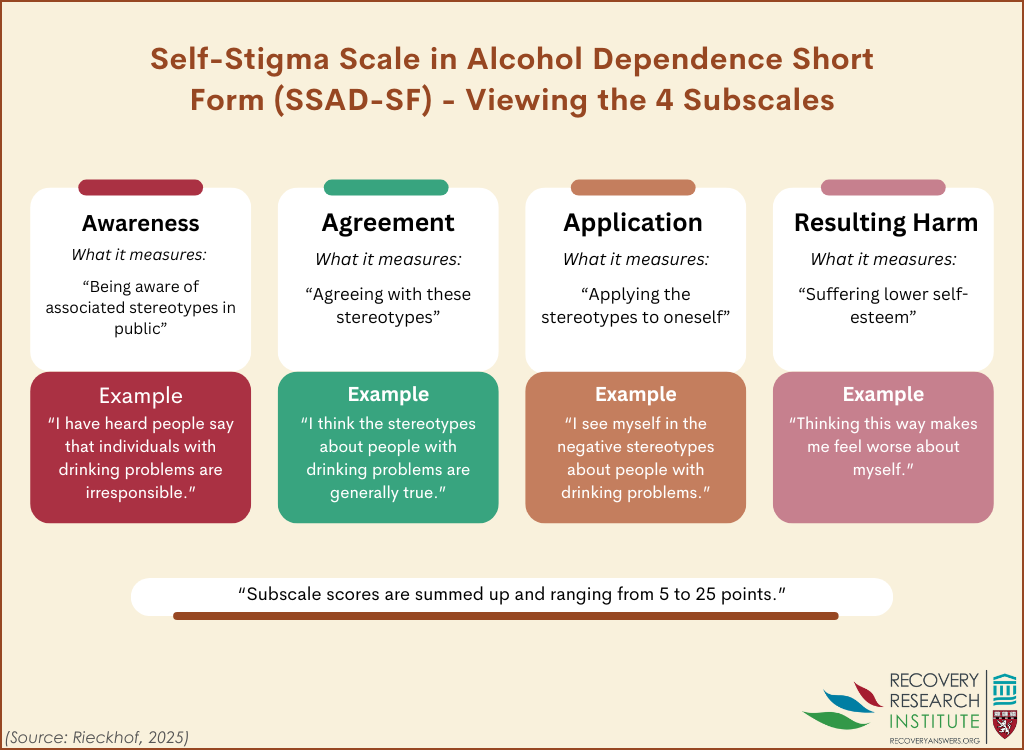

This study utilized a comparative design to develop a shortened version of the Self-Stigma in Alcohol Dependence Scale. This scale is designed to measure how much individuals internalize stereotypes about people with an alcohol use disorder. The scale lists 16 stereotypes about people with alcohol use disorder and across 4 subscales: stereotype awareness (aware), stereotype agreement (agree), stereotype application (apply), and self-esteem decrement (harm). See graphic below for scale information and example items.

Aware subscale items are designed to assess how much people are aware of negative stereotypes of people with alcohol use disorder (e.g., “I think the public believes… most people with alcohol problems are unable to get or keep a regular job.”).

Agree subscale items are designed to assess how much people agree with negative stereotypes of people with alcohol use disorder (e.g., “I think most people with alcohol problems are unpredictable.”).

Apply subscale items are designed to measure the degree to which people feel negative stereotypes about those with an alcohol use disorder apply to them (e.g., “Because I have alcohol use problems… I am emotionally unstable.” )

Harm subscale items are designed to assess the degree to which people believe alcohol has negatively impacted their self-esteem (e.g., “I currently respect myself less, because… I will never get away from alcohol.”) Items are answered with a 5-point Likert scale from 1 ´I strongly disagree´ to 5 ´I strongly agree´.

To shorten the original scale, first the authors polled alcohol use disorder self-help group participants to determine which items to remove. The authors asked 12 participants to rank how offensive each listed stereotype was on a 5-point scale (5 being the most offensive). Items above the average offensiveness score (3.3) were removed from the revised measure. Second, the authors administered the revised scale to people receiving alcohol use disorder treatment then used statistical analysis to determine psychometric properties of the remaining items, such as how consistently participants responded to each item. The authors then compared data used to validate the original (64-item) scale with the responses to the shortened (20-item) scale. That is, they compared how well both versions predicted psychological constructs associated with self-stigma.

To assess the validity of the revised scale, the authors measured the extent to which the self-stigma items predicted constructs associated with self-stigma: negative self-esteem, shame, and drinking-refusal self-efficacy. They controlled statistically for depressive symptoms and gender to determine whether the scale was independently related to these constructs. Self-esteem was measured via the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, a 10-item measure (score range 0–30), with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem. To assess shame, the authors used a single item: “I feel ashamed because I have an alcohol problem” with responses via a 5-point Likert scale. Finally, drinking-refusal self-efficacy was assessed via the Short Questionnaire on Abstinence Confidence . Participants were asked to rate their confidence in being able to resist using alcohol across multiple contexts via a 10-point scale (´not confident at all´ to ´totally confident´). Depressive Symptoms were measured via the Patient Health Questionnaire 8-item depression scale. Participants reported the frequency of 8 depression symptoms as experienced within the past 2 weeks. Scale scores ranged from 0 (none) to 24 (severe). Gender was measured via a self-administered demographic survey (male or female only).

Participants for the current study were recruited from a psychiatric substance use treatment facility, an outpatient addiction counseling center, or a self-help group in Saxony, Germany. Participant recruitment took place between March 2021 and June 2022. Eligible participants 1) were 18 years or older and 2) self-identified as hav¬ing an alcohol-related problem (e.g., alcohol use disorder).

This study consisted of 156 people. The sample was majority male (60.3%). Participants’ ages were recorded as ranges: 21-35 (11.9%) 36-50 (46.7%) 51-65(39.3%) and ≥66 (5.2%). Just under half of the participants (48.1%) were in a relationship (e.g., married). Half of participants (50%) were employed. At the time of the study, most participants had not been abstinent from substances over the previous 6 months (78.2%).

The revised scale performed well

When compared to the original scale development data, the revised Self-Stigma in Alcohol Dependence Scale was shown to be comparably reliable. In addition, the revised scale was shown to have good internal consistency – a measure of how well the items “hang together” and appear to measure the same thing reliably.

Self-stigma predicted shame, self-esteem, and drinking refusal self-efficacy

People who reported higher self-stigma (specifically apply and harm subdomains) were more likely to report elevated shame, lower self-esteem, and believed they would be less able to abstain from alcohol use in the future.

Self-stigma was more predictive of drinking-refusal self-efficacy than depressive symptoms

When statistical models included both depressive symptoms and self-stigma, it was found that self-stigma was a better predictor of drinking-refusal self-efficacy than depressive symptoms. Although gender was included in all models, the only significant difference was shame: women reported significantly higher shame than men.

The shortened version of the self-stigma scale could well be just as useful a tool for measuring internalized alcohol use disorder stereotypes. Results of psychometric testing revealed that compared to the original longer version of the scale, the shortened version provided comparable results. In addition, the validity of the shortened version was confirmed via its association with shame, self-esteem, and drinking refusal self-efficacy.

Given these results, the shortened version of the self-stigma scale could be a useful tool in clinical settings. The revised 20-item scale would be more feasible to implement in clinical settings than the original 64-item scale. That said, a large number of items were omitted which may have been useful to generate conversation and discussion. So, the utility of the short form may depend on the goals for its use. For speedier assessment and to reduce participant time burdens in research studies where a single total scale score is used, the short form may be particularly useful. In contrast, for generating conversation about self-stigmas in a therapy or other clinical contexts, the longer form may add useful dimensions or individual items that are omitted when all 64 items in the longer form are subjected to computerized psychometric analysis focused solely on reducing scale length while maintaining numeric comparability in terms of reliability coefficients. By implementing this shorter scale in clinical settings, providers may be able to more rapidly identify individuals with alcohol use disorder with high self-stigma that could then be discussed and ameliorated to prevent dropout from treatment. This could, for example, facilitate a process whereby patients may come to understand how their internalization of stereotypes may impact their perceptions of self-esteem and behavior. In addition, this scale could be a valuable tool for clinicians by identifying patients who may have difficulty sticking with treatment due to stigma. Clinicians may work to address self-stigma with patients (e.g., through discussion or brief motivational interventions) to facilitate substance use treatment seeking.

Overall, while this is an important area of research, this study did not measure the association between self-stigma and recovery outcomes (e.g., alcohol use post-treatment). However, alcohol refusal self-efficacy is associated with alcohol use. Furthermore, the results may have been impacted by the fact all participants were recruited from treatment settings (e.g., in-patient psychiatric treatment facilities undergoing alcohol detoxification), restricting the range of potential scores on the measure and related estimates of self-stigma. It may be useful to see how self-stigma prevents people from attending services altogether. More research is needed to more clearly demonstrate how self-stigma may be predictive of alcohol use disorder treatment engagement and outcomes in a broader sample.

This study found that a shortened version of the Self-Stigma in Alcohol Dependence Scale was a reliable and valid measure of self-stigma among participants with alcohol use disorder. Higher self-stigma in people with alcohol use disorder was associated with lower self-esteem, more shame, and less drinking-refusal self-efficacy. This self-stigma measure could be implemented in clinical settings and in research studies to help explore the role self-stigma plays in patients’ recovery. However, this study did not determine how self-stigma among participants was associated with treatment engagement or outcomes (e.g., alcohol abstinence). Further research is needed to understand the role of self-stigma on substance use disorder treatment seeking, efficacy, and health outcomes.

Rieckhof, S., Leonhard, A., Schindler, S., Lüders, J., Tschentscher, N., Speerforck, S., Corrigan, P. W., & Schomerus, G. (2024). Self-stigma in alcohol dependence scale: Development and validity of the short form. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1), 735. doi: 10.1186/s12888-024-06187-z.

l

People may internalize negative attitudes and stereotypes about groups to which they belong in a process dubbed “self-stigma”. For example, people who engage in problematic alcohol use may come to recognize symptoms of their disorder they are experiencing as a personal failing. Such internalizing of stigma can lead to feelings of shame and reduced self-esteem which can lead to a ´why try´ effect: an individual’s self-worth is lowered so much that they no longer pursue personal goals (e.g., career milestones) and/or abandon self-care practices (e.g., pursuing medical treatment). Fear of stigma among people with alcohol use disorder can be especially pernicious as it could impact treatment outcomes.

Evidence suggests some patients may avoid substance use disorder treatment out of fear of stigmatization. Furthermore, self-stigma is associated with lower perceived ability to abstain from alcohol use in the future among patients undergoing alcohol use disorder treatment. Assessing self-stigma among patients in clinical settings could identify those who may benefit from alcohol use disorder treatment but who avoid care. However current measures of self-stigma are long and challenging to implement. The Self-Stigma in Alcohol Dependence Scale is 64 items long which may not be feasible to use clinical settings. There is a need for briefer scales which can be used in real world healthcare and recovery support service settings, as well as in research contexts where participant time burden is often an issue. To this end, this study tested and validated a shortened version of the Self-Stigma in Alcohol Dependence Scale and examined relevant factors associated with self-stigma.

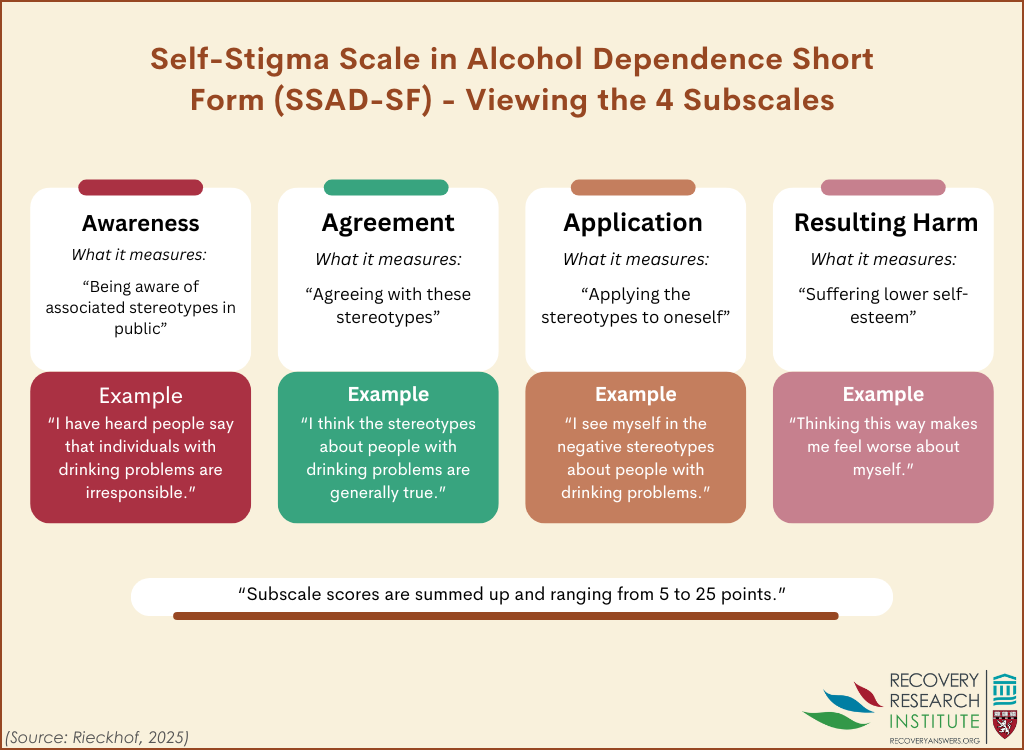

This study utilized a comparative design to develop a shortened version of the Self-Stigma in Alcohol Dependence Scale. This scale is designed to measure how much individuals internalize stereotypes about people with an alcohol use disorder. The scale lists 16 stereotypes about people with alcohol use disorder and across 4 subscales: stereotype awareness (aware), stereotype agreement (agree), stereotype application (apply), and self-esteem decrement (harm). See graphic below for scale information and example items.

Aware subscale items are designed to assess how much people are aware of negative stereotypes of people with alcohol use disorder (e.g., “I think the public believes… most people with alcohol problems are unable to get or keep a regular job.”).

Agree subscale items are designed to assess how much people agree with negative stereotypes of people with alcohol use disorder (e.g., “I think most people with alcohol problems are unpredictable.”).

Apply subscale items are designed to measure the degree to which people feel negative stereotypes about those with an alcohol use disorder apply to them (e.g., “Because I have alcohol use problems… I am emotionally unstable.” )

Harm subscale items are designed to assess the degree to which people believe alcohol has negatively impacted their self-esteem (e.g., “I currently respect myself less, because… I will never get away from alcohol.”) Items are answered with a 5-point Likert scale from 1 ´I strongly disagree´ to 5 ´I strongly agree´.

To shorten the original scale, first the authors polled alcohol use disorder self-help group participants to determine which items to remove. The authors asked 12 participants to rank how offensive each listed stereotype was on a 5-point scale (5 being the most offensive). Items above the average offensiveness score (3.3) were removed from the revised measure. Second, the authors administered the revised scale to people receiving alcohol use disorder treatment then used statistical analysis to determine psychometric properties of the remaining items, such as how consistently participants responded to each item. The authors then compared data used to validate the original (64-item) scale with the responses to the shortened (20-item) scale. That is, they compared how well both versions predicted psychological constructs associated with self-stigma.

To assess the validity of the revised scale, the authors measured the extent to which the self-stigma items predicted constructs associated with self-stigma: negative self-esteem, shame, and drinking-refusal self-efficacy. They controlled statistically for depressive symptoms and gender to determine whether the scale was independently related to these constructs. Self-esteem was measured via the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, a 10-item measure (score range 0–30), with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem. To assess shame, the authors used a single item: “I feel ashamed because I have an alcohol problem” with responses via a 5-point Likert scale. Finally, drinking-refusal self-efficacy was assessed via the Short Questionnaire on Abstinence Confidence . Participants were asked to rate their confidence in being able to resist using alcohol across multiple contexts via a 10-point scale (´not confident at all´ to ´totally confident´). Depressive Symptoms were measured via the Patient Health Questionnaire 8-item depression scale. Participants reported the frequency of 8 depression symptoms as experienced within the past 2 weeks. Scale scores ranged from 0 (none) to 24 (severe). Gender was measured via a self-administered demographic survey (male or female only).

Participants for the current study were recruited from a psychiatric substance use treatment facility, an outpatient addiction counseling center, or a self-help group in Saxony, Germany. Participant recruitment took place between March 2021 and June 2022. Eligible participants 1) were 18 years or older and 2) self-identified as hav¬ing an alcohol-related problem (e.g., alcohol use disorder).

This study consisted of 156 people. The sample was majority male (60.3%). Participants’ ages were recorded as ranges: 21-35 (11.9%) 36-50 (46.7%) 51-65(39.3%) and ≥66 (5.2%). Just under half of the participants (48.1%) were in a relationship (e.g., married). Half of participants (50%) were employed. At the time of the study, most participants had not been abstinent from substances over the previous 6 months (78.2%).

The revised scale performed well

When compared to the original scale development data, the revised Self-Stigma in Alcohol Dependence Scale was shown to be comparably reliable. In addition, the revised scale was shown to have good internal consistency – a measure of how well the items “hang together” and appear to measure the same thing reliably.

Self-stigma predicted shame, self-esteem, and drinking refusal self-efficacy

People who reported higher self-stigma (specifically apply and harm subdomains) were more likely to report elevated shame, lower self-esteem, and believed they would be less able to abstain from alcohol use in the future.

Self-stigma was more predictive of drinking-refusal self-efficacy than depressive symptoms

When statistical models included both depressive symptoms and self-stigma, it was found that self-stigma was a better predictor of drinking-refusal self-efficacy than depressive symptoms. Although gender was included in all models, the only significant difference was shame: women reported significantly higher shame than men.

The shortened version of the self-stigma scale could well be just as useful a tool for measuring internalized alcohol use disorder stereotypes. Results of psychometric testing revealed that compared to the original longer version of the scale, the shortened version provided comparable results. In addition, the validity of the shortened version was confirmed via its association with shame, self-esteem, and drinking refusal self-efficacy.

Given these results, the shortened version of the self-stigma scale could be a useful tool in clinical settings. The revised 20-item scale would be more feasible to implement in clinical settings than the original 64-item scale. That said, a large number of items were omitted which may have been useful to generate conversation and discussion. So, the utility of the short form may depend on the goals for its use. For speedier assessment and to reduce participant time burdens in research studies where a single total scale score is used, the short form may be particularly useful. In contrast, for generating conversation about self-stigmas in a therapy or other clinical contexts, the longer form may add useful dimensions or individual items that are omitted when all 64 items in the longer form are subjected to computerized psychometric analysis focused solely on reducing scale length while maintaining numeric comparability in terms of reliability coefficients. By implementing this shorter scale in clinical settings, providers may be able to more rapidly identify individuals with alcohol use disorder with high self-stigma that could then be discussed and ameliorated to prevent dropout from treatment. This could, for example, facilitate a process whereby patients may come to understand how their internalization of stereotypes may impact their perceptions of self-esteem and behavior. In addition, this scale could be a valuable tool for clinicians by identifying patients who may have difficulty sticking with treatment due to stigma. Clinicians may work to address self-stigma with patients (e.g., through discussion or brief motivational interventions) to facilitate substance use treatment seeking.

Overall, while this is an important area of research, this study did not measure the association between self-stigma and recovery outcomes (e.g., alcohol use post-treatment). However, alcohol refusal self-efficacy is associated with alcohol use. Furthermore, the results may have been impacted by the fact all participants were recruited from treatment settings (e.g., in-patient psychiatric treatment facilities undergoing alcohol detoxification), restricting the range of potential scores on the measure and related estimates of self-stigma. It may be useful to see how self-stigma prevents people from attending services altogether. More research is needed to more clearly demonstrate how self-stigma may be predictive of alcohol use disorder treatment engagement and outcomes in a broader sample.

This study found that a shortened version of the Self-Stigma in Alcohol Dependence Scale was a reliable and valid measure of self-stigma among participants with alcohol use disorder. Higher self-stigma in people with alcohol use disorder was associated with lower self-esteem, more shame, and less drinking-refusal self-efficacy. This self-stigma measure could be implemented in clinical settings and in research studies to help explore the role self-stigma plays in patients’ recovery. However, this study did not determine how self-stigma among participants was associated with treatment engagement or outcomes (e.g., alcohol abstinence). Further research is needed to understand the role of self-stigma on substance use disorder treatment seeking, efficacy, and health outcomes.

Rieckhof, S., Leonhard, A., Schindler, S., Lüders, J., Tschentscher, N., Speerforck, S., Corrigan, P. W., & Schomerus, G. (2024). Self-stigma in alcohol dependence scale: Development and validity of the short form. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1), 735. doi: 10.1186/s12888-024-06187-z.

l

People may internalize negative attitudes and stereotypes about groups to which they belong in a process dubbed “self-stigma”. For example, people who engage in problematic alcohol use may come to recognize symptoms of their disorder they are experiencing as a personal failing. Such internalizing of stigma can lead to feelings of shame and reduced self-esteem which can lead to a ´why try´ effect: an individual’s self-worth is lowered so much that they no longer pursue personal goals (e.g., career milestones) and/or abandon self-care practices (e.g., pursuing medical treatment). Fear of stigma among people with alcohol use disorder can be especially pernicious as it could impact treatment outcomes.

Evidence suggests some patients may avoid substance use disorder treatment out of fear of stigmatization. Furthermore, self-stigma is associated with lower perceived ability to abstain from alcohol use in the future among patients undergoing alcohol use disorder treatment. Assessing self-stigma among patients in clinical settings could identify those who may benefit from alcohol use disorder treatment but who avoid care. However current measures of self-stigma are long and challenging to implement. The Self-Stigma in Alcohol Dependence Scale is 64 items long which may not be feasible to use clinical settings. There is a need for briefer scales which can be used in real world healthcare and recovery support service settings, as well as in research contexts where participant time burden is often an issue. To this end, this study tested and validated a shortened version of the Self-Stigma in Alcohol Dependence Scale and examined relevant factors associated with self-stigma.

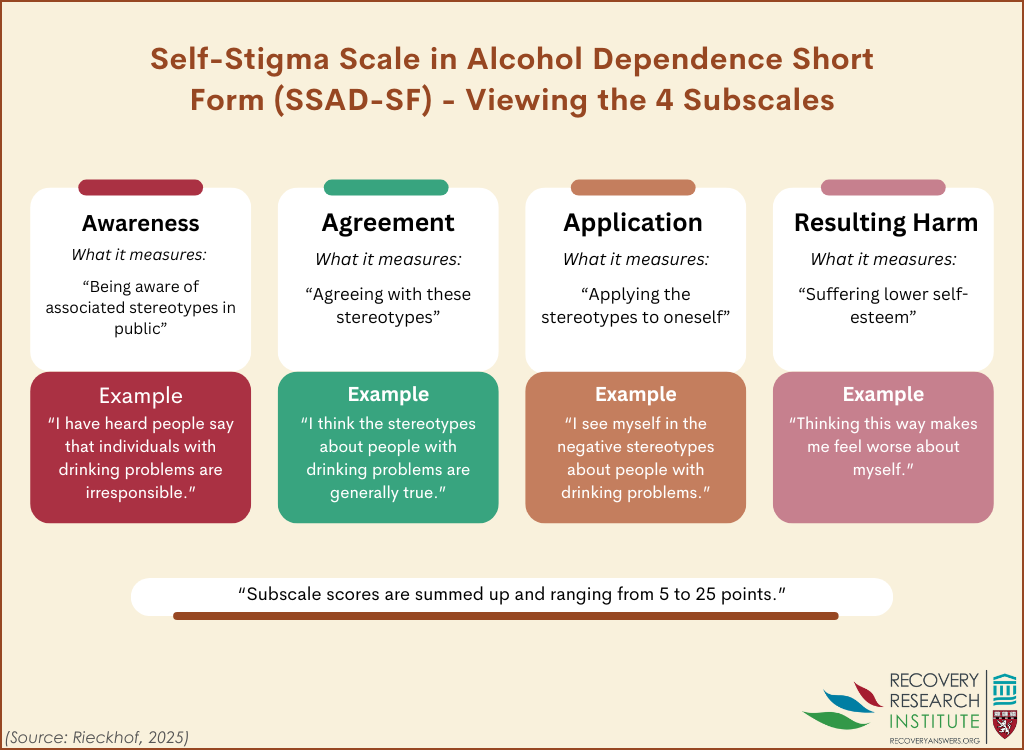

This study utilized a comparative design to develop a shortened version of the Self-Stigma in Alcohol Dependence Scale. This scale is designed to measure how much individuals internalize stereotypes about people with an alcohol use disorder. The scale lists 16 stereotypes about people with alcohol use disorder and across 4 subscales: stereotype awareness (aware), stereotype agreement (agree), stereotype application (apply), and self-esteem decrement (harm). See graphic below for scale information and example items.

Aware subscale items are designed to assess how much people are aware of negative stereotypes of people with alcohol use disorder (e.g., “I think the public believes… most people with alcohol problems are unable to get or keep a regular job.”).

Agree subscale items are designed to assess how much people agree with negative stereotypes of people with alcohol use disorder (e.g., “I think most people with alcohol problems are unpredictable.”).

Apply subscale items are designed to measure the degree to which people feel negative stereotypes about those with an alcohol use disorder apply to them (e.g., “Because I have alcohol use problems… I am emotionally unstable.” )

Harm subscale items are designed to assess the degree to which people believe alcohol has negatively impacted their self-esteem (e.g., “I currently respect myself less, because… I will never get away from alcohol.”) Items are answered with a 5-point Likert scale from 1 ´I strongly disagree´ to 5 ´I strongly agree´.

To shorten the original scale, first the authors polled alcohol use disorder self-help group participants to determine which items to remove. The authors asked 12 participants to rank how offensive each listed stereotype was on a 5-point scale (5 being the most offensive). Items above the average offensiveness score (3.3) were removed from the revised measure. Second, the authors administered the revised scale to people receiving alcohol use disorder treatment then used statistical analysis to determine psychometric properties of the remaining items, such as how consistently participants responded to each item. The authors then compared data used to validate the original (64-item) scale with the responses to the shortened (20-item) scale. That is, they compared how well both versions predicted psychological constructs associated with self-stigma.

To assess the validity of the revised scale, the authors measured the extent to which the self-stigma items predicted constructs associated with self-stigma: negative self-esteem, shame, and drinking-refusal self-efficacy. They controlled statistically for depressive symptoms and gender to determine whether the scale was independently related to these constructs. Self-esteem was measured via the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, a 10-item measure (score range 0–30), with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem. To assess shame, the authors used a single item: “I feel ashamed because I have an alcohol problem” with responses via a 5-point Likert scale. Finally, drinking-refusal self-efficacy was assessed via the Short Questionnaire on Abstinence Confidence . Participants were asked to rate their confidence in being able to resist using alcohol across multiple contexts via a 10-point scale (´not confident at all´ to ´totally confident´). Depressive Symptoms were measured via the Patient Health Questionnaire 8-item depression scale. Participants reported the frequency of 8 depression symptoms as experienced within the past 2 weeks. Scale scores ranged from 0 (none) to 24 (severe). Gender was measured via a self-administered demographic survey (male or female only).

Participants for the current study were recruited from a psychiatric substance use treatment facility, an outpatient addiction counseling center, or a self-help group in Saxony, Germany. Participant recruitment took place between March 2021 and June 2022. Eligible participants 1) were 18 years or older and 2) self-identified as hav¬ing an alcohol-related problem (e.g., alcohol use disorder).

This study consisted of 156 people. The sample was majority male (60.3%). Participants’ ages were recorded as ranges: 21-35 (11.9%) 36-50 (46.7%) 51-65(39.3%) and ≥66 (5.2%). Just under half of the participants (48.1%) were in a relationship (e.g., married). Half of participants (50%) were employed. At the time of the study, most participants had not been abstinent from substances over the previous 6 months (78.2%).

The revised scale performed well

When compared to the original scale development data, the revised Self-Stigma in Alcohol Dependence Scale was shown to be comparably reliable. In addition, the revised scale was shown to have good internal consistency – a measure of how well the items “hang together” and appear to measure the same thing reliably.

Self-stigma predicted shame, self-esteem, and drinking refusal self-efficacy

People who reported higher self-stigma (specifically apply and harm subdomains) were more likely to report elevated shame, lower self-esteem, and believed they would be less able to abstain from alcohol use in the future.

Self-stigma was more predictive of drinking-refusal self-efficacy than depressive symptoms

When statistical models included both depressive symptoms and self-stigma, it was found that self-stigma was a better predictor of drinking-refusal self-efficacy than depressive symptoms. Although gender was included in all models, the only significant difference was shame: women reported significantly higher shame than men.

The shortened version of the self-stigma scale could well be just as useful a tool for measuring internalized alcohol use disorder stereotypes. Results of psychometric testing revealed that compared to the original longer version of the scale, the shortened version provided comparable results. In addition, the validity of the shortened version was confirmed via its association with shame, self-esteem, and drinking refusal self-efficacy.

Given these results, the shortened version of the self-stigma scale could be a useful tool in clinical settings. The revised 20-item scale would be more feasible to implement in clinical settings than the original 64-item scale. That said, a large number of items were omitted which may have been useful to generate conversation and discussion. So, the utility of the short form may depend on the goals for its use. For speedier assessment and to reduce participant time burdens in research studies where a single total scale score is used, the short form may be particularly useful. In contrast, for generating conversation about self-stigmas in a therapy or other clinical contexts, the longer form may add useful dimensions or individual items that are omitted when all 64 items in the longer form are subjected to computerized psychometric analysis focused solely on reducing scale length while maintaining numeric comparability in terms of reliability coefficients. By implementing this shorter scale in clinical settings, providers may be able to more rapidly identify individuals with alcohol use disorder with high self-stigma that could then be discussed and ameliorated to prevent dropout from treatment. This could, for example, facilitate a process whereby patients may come to understand how their internalization of stereotypes may impact their perceptions of self-esteem and behavior. In addition, this scale could be a valuable tool for clinicians by identifying patients who may have difficulty sticking with treatment due to stigma. Clinicians may work to address self-stigma with patients (e.g., through discussion or brief motivational interventions) to facilitate substance use treatment seeking.

Overall, while this is an important area of research, this study did not measure the association between self-stigma and recovery outcomes (e.g., alcohol use post-treatment). However, alcohol refusal self-efficacy is associated with alcohol use. Furthermore, the results may have been impacted by the fact all participants were recruited from treatment settings (e.g., in-patient psychiatric treatment facilities undergoing alcohol detoxification), restricting the range of potential scores on the measure and related estimates of self-stigma. It may be useful to see how self-stigma prevents people from attending services altogether. More research is needed to more clearly demonstrate how self-stigma may be predictive of alcohol use disorder treatment engagement and outcomes in a broader sample.

This study found that a shortened version of the Self-Stigma in Alcohol Dependence Scale was a reliable and valid measure of self-stigma among participants with alcohol use disorder. Higher self-stigma in people with alcohol use disorder was associated with lower self-esteem, more shame, and less drinking-refusal self-efficacy. This self-stigma measure could be implemented in clinical settings and in research studies to help explore the role self-stigma plays in patients’ recovery. However, this study did not determine how self-stigma among participants was associated with treatment engagement or outcomes (e.g., alcohol abstinence). Further research is needed to understand the role of self-stigma on substance use disorder treatment seeking, efficacy, and health outcomes.

Rieckhof, S., Leonhard, A., Schindler, S., Lüders, J., Tschentscher, N., Speerforck, S., Corrigan, P. W., & Schomerus, G. (2024). Self-stigma in alcohol dependence scale: Development and validity of the short form. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1), 735. doi: 10.1186/s12888-024-06187-z.

151 Merrimac St., 4th Floor. Boston, MA 02114