Scientific Rigor Versus Useful Science

Understanding who is and who is not included in substance use disorder treatment research is critical for assessing the utility and applicability of the results to real-world clinical settings.

This systematic review investigated such questions as what percentage of participants are excluded, why they are excluded, and how does that alter the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample?

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

In substance use disorder treatment research restrictive exclusion criteria is often imposed in the participant screening processes. Exclusion criteria set by investigators are used to ensure patient safety to the new intervention being tested and to test this new intervention under optimal conditions. If the intervention does not work under these optimal conditions, it is unlikely to work in more complicated, real-world settings.

The practice of excluding individuals to achieve these optimal conditions criteria, however, comes with a cost. Restrictive exclusion criteria can reduce external validity (the extent to which the results can be generalized to other people), reduce clinicians’ willingness to apply research findings if characteristics of their clinical population are not represented in trial samples, and may also bias (inflate or deflate) estimates of treatment effects. The full extent of these problems has not been systematically determined through a thorough review of the literature and critical analysis.

This review of dozens of studies filled the knowledge gap on:

- what exclusion criteria has been used in the field of treatment for alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use disorders

- estimates of overall exclusion rates

- the impact of exclusion criteria on sample representativeness or results

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This review of the literature was conducted by searching PubMed (a database that provides free access to science journals) on the following terms: ‘eligibility criteria and generalizability’, ‘exclusion criteria and generalizability’, ‘eligibility criteria’ and ‘exclusion criteria’. The initial literature review was conducted in 2013, with an update of the search in 2014 and additional studies added in 2016.

Studies were included if they analyzed data on:

(i) the prevalence and nature of exclusion criteria in a particular field; and/or

(ii) the impact of exclusion criteria on sample representativeness or study results.

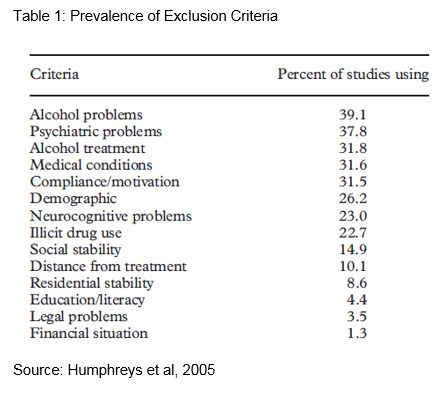

From this pool of literature, the review focused on alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use disorders as opposed to other diseases that emerged. The studies examined are simulation studies of reviews of treatment research, but not individual treatment studies themselves. The search processes yielded a final 22 studies included in this qualitative synthesis. The authors identified a list of 14 exclusion criteria used in treatment trials. Over 25% of the studies did not mention exclusion criteria, and the average number of criteria reported by studies was four.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

‘Alcohol problems’ was the most commonly used exclusion criterion (meaning formal diagnosis versus other degree of severity) used in 39% of studies

‘Psychiatric problems’ was used by almost 38% of the studies which makes it the second most commonly used criterion

The exclusion criteria listed in Table 1 that appear to alter (increase or decrease) the sample size most substantially are:

- alcohol treatment (previous or current)

- compliance/motivation, medical problems

- legal problems

- other drug use outside of the primary substance being treated.

Furthermore, an important caveat to mention is that the proportion of participants excluded by each criterion varied widely depending on if it was a treatment versus non-treatment seeking sample, or a public versus private sector sample. For example, one study found that only 15% of the non-treatment seeking sample would have been excluded under the legal problem criterion compared to 40% in treatment-seeking participants. Another study reported that 70% of participants from public-sector settings would be excluded under social stability (e.g. being unmarried and unemployed) compared with only 41% from private settings.

Next, overall exclusion rates were estimated by calculating the proportion of participants excluded when all the criteria were combined.

The following studies simulated trial enrollment procedures by applying exclusion criteria to nationally representative samples (e.g. National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), which had over 40,000 participants) and calculated overall percentages of participants excluded.

Le Strat and colleagues (2011) found 66% of community-dwelling smokers compared to 59% of motivated-to-quit smokers would be excluded from a study of treatment for tobacco dependence. Okuda and colleagues (2010) found that 80% of community-dwelling cannabis-dependent individuals would be excluded from clinical trials on treatment for cannabis dependence according to the criteria in Table 1. The authors of this review concluded that overall exclusion typically ranges from 64 to 96% for treatment studies of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use disorders.

- Blanco and colleagues (2008)

-

Blanco and colleagues (2008) found 50% of community-dwelling versus 79% of treatment seeking participants would be excluded from clinical trial enrollment according to Table (above) criteria. Storbjork (2014) found that 95.7% of potential participants were excluded after applying Table 1 criteria to 1,153 treated individuals who were diagnosed with alcohol dependence.

- Le Strat and colleagues (2011)

-

Le Strat and colleagues (2011) found 66% of community-dwelling smokers compared to 59% of motivated-to-quit smokers would be excluded from a study of treatment for tobacco dependence.

- Okuda and colleagues (2010)

-

Okuda and colleagues (2010) found that 80% of community-dwelling cannabis-dependent individuals would be excluded from clinical trials on treatment for cannabis dependence according to the criteria in Table (above). The authors of this review concluded that overall exclusion typically ranges from 64 to 96% for treatment studies of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use disorders.

The authors also described a couple of studies that examined if individuals with substance use disorder were eligible to participate in clinical trials at rates similar to patients with other chronic conditions.

- Stirman and colleagues (2003)

-

Stirman and colleagues (2003) examination of medical charts revealed that 80% of patients being treated for conditions other than substance use disorder would qualify for at least one clinical trial, but only 31% of the patients with substance use disorder would have been eligible for at least one clinical trial of substance use disorder treatment. Patients with substance use disorder were eligible at much lower rates for multiple randomized trials as well: only 15% would have been eligible for at least two trials versus 70% of patients with other disorders.

In a Stirman replication study, at least half of the patients with psychiatric diagnoses were eligible for at least one study with the exception of patients with substance use disorder. In addition, none of the patients with substance use disorder were eligible for clinical trials for substance use disorder treatment.

The most common exclusion reasons were the patient was using other substances in addition to the primary substance or the patient was in partial remission.

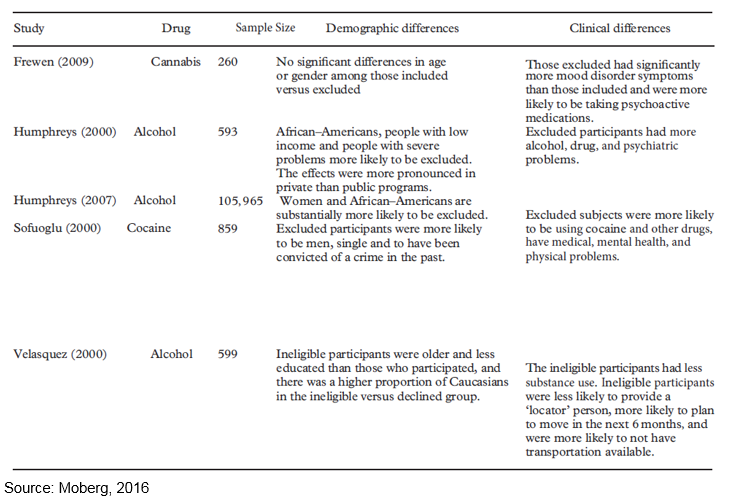

In order to obtain a sense of the degree to which included participants are representative of excluded participants, the Table below lists five studies and describes demographic and clinical differences between included and excluded participants.

Overall, the results of these five studies show included versus excluded samples can be altered on demographic differences (race, gender, age, and socioeconomic status), substance use history, comorbidities, medications, and extent of criminal involvement.

Last, there was one study which examined the effect of eligibility criteria on study outcomes and tested the hypothesis that exclusion criteria increase statistical power (ability to detect if the intervention worked) by decreasing differences in sample characteristics. They tested this because a particular treatment could appear more or less effective depending on how varied the sample is in terms of characteristics. Using a representative sample of 1,445 patients, they reported that applying exclusion criteria decreased statistical power as evidenced by larger rather than smaller confidence intervals (a measure of statistical accuracy).

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

This review of the literature has shed light on who is and who is not in the substance use disorder treatment research which is necessary for assessing the utility and generalizability of the research to real-world community and clinical settings.

The authors concluded that overall exclusion typically ranges from 64 to 96% for treatment studies of alcohol, tobacco & illicit drug use disorders.

- Dennis et al. (2015)

-

Similarly, Dennis et al. (2015) conducted a systematic review of exclusion rates for clinical trials of opioid agonist and antagonist therapies and reported rates of exclusion up to 70% when applying the criteria identified in the literature to a sample of patients with opioid use disorder.

The current review reported the criteria which excluded the highest percentage of potential participants were substance use disorder treatment (current or previous), low compliance or motivation, medical problems, other drug use in addition to the primary substance, and legal problems.

Dennis and colleagues found that the presence of a psychiatric comorbidity, secondary substance use disorder, chronic physical comorbidity, or psychotropic medications excluded the highest proportion of participants when applied to an independent sample.

Taken together, these two studies raise concerns around the degree to which trial samples are representative of other clinical populations with a substance use disorder.

Dennis and colleagues also highlighted the importance of using representative samples in medication trials. Unintended harm can come to patients in the general clinical population when they use a medication that was tested on a highly specific group that they themselves do not represent. The patients may experience side effects that were not apparent during a tightly controlled trial due to similarities in sample characteristics (e.g., lack of psychiatric conditions).

Use of exclusion criteria can substantially alter the representativeness of demographic and clinical characteristics of treatment research samples, including characteristics other than those explicitly addressed by the criteria. Specifically, substance use disorder treatment studies tended to exclude participants with more severe co-morbid medical, psychiatric, and social problems. Findings on gender were less consistent. Regarding racial background, on the whole, African Americans tended to be more likely to be excluded.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Similar to any systematic literature reviews, the quality of the review is limited by the quality of previously published research. In this case, several of the studies did not report raw data or exclusion rates, therefore, definitive overall exclusion rates could not be calculated. In fact, over 25% of the identified studies did not mention exclusion criteria. Perhaps the studies had no exclusion criteria or the research team failed to report the criteria used.

NEXT STEPS

Future research should explore the impact of having less restrictive exclusion criteria on outcomes. This will allow a better understanding of how the treatment being tested impacts other conditions that may have otherwise been excluded, and how individual characteristics of the sample might influence treatment effectiveness.

For example, the clinical trials network (CTN) was designed to improve the quality of treatment for substance use disorder. In doing so, they have delineated between treatments that have been tested for efficacy (internal validity is over emphasized with exclusion criteria) versus the next phase of research when a treatment is tested for effectiveness in ‘real world’ settings (external validity is over emphasized). Failures to translate research into practice arise when treatments that were developed in efficacy trials are applied to the larger population of individuals with a substance use disorder before being tested in effectiveness trials.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Currently many clinical trials have restrictive exclusion criteria that help to protect patient safety and ensure that a treatment effect can be detected if it is present. As a consequence, some common conditions found in real-world community populations or treatment seeking populations are not always as represented in clinical trials. This review suggests that researchers thoroughly document sample characteristics of the included and excluded samples and carefully consider when exclusion criteria are necessary in order to make results more applicable to more individuals and families seeking recovery. Furthermore, journal editors can require that exclusion criteria be addressed in published studies to enhance transparency about how the final sample was selected.

- For Scientists: The present review strongly supports the conclusion that exclusion criteria have significant costs in terms of external validity. Substance use disorder treatment researchers should therefore critically evaluate the rationale for and specific operationalization of any exclusion criterion they employ, even if it has been used in other studies before.

- For Policy makers: This systematic review has shown that restrictive exclusion criteria imposed on trial samples can have a substantial cost in terms of generalizability. Consider prioritizing funding to investigate how treatments tested in trial samples can influence participants who are traditionally excluded, real-world clinical populations, and community samples with a substance use disorder.

- For Treatment professionals and treatment systems: Based on this review, you may find that some of your clinical patients have characteristics that were not represented in the trials for individuals with substance use disorder. As a result, treatments that you may implement in your program or practice based on clinical trial evidence, may produce different results that will vary depending on how similar or different your patients are relative to those studied and on which the evidence is based.

CITATIONS

Moberg, C. A. & Humphreys, K. 2016. Exclusion criteria in treatment research on alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use disorders: A review and critical analysis. Drug and Alcohol Review, 00-000. DOI: 10.1111/dar.12438