Alcoholics Anonymous Reduces Depression?

Many researchers, clinicians, and recovering individuals, themselves, think of recovery from substance use disorder (SUD) as an experience that includes, but is not limited to, abstinence from alcohol and other drugs.

For many, recovery is also defined by efforts toward personal growth more generally, including improved psychological and emotional well-being.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Dozens of studies show that 12-step mutual-help organization (MHO) participation and treatments designed to facilitate involvement with groups like Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) help increase an individual’s likelihood of abstinence from alcohol and other drugs, while also curbing health care costs (see here, for a review). More is known about the benefits of participating in 12-step MHOs during the first year of recovery, or directly after treatment discharge, but attendance may offer abstinence benefits over the course of several years as well (see here).

Despite these informative studies on the positive effects of 12-step MHO participation on abstinence, research examining the impact of attendance on recovery markers beyond abstinence is far less common.

This Wilcox et al. study investigated whether there was an effect of AA attendance, and other markers of AA participation including religious/spiritual practices and 12-step work, on decreased depression over 2 years among new AA participants with alcohol use disorder.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Researchers assessed 253 adults with alcohol use disorder, who reported at least one drinking day and had attended at least one 12-step MHO meeting in the past 90 days, but had less than 16 total weeks of lifetime AA attendance. They established these inclusion criteria to investigate the effects of AA participation in newAA members. Many prior studies have included both AA-naive and AA-experienced individuals. More research is needed on investigating the effect of AA attendance for those with minimal prior experience to inform clinical recommendations and public health policy.

The study assessed participants at intake into the study, and again at 3-, 6-, 9-, 12-, 18- and 24-month follow-ups. Two-thirds of the sample was male and the majority had at least a high school diploma or general equivalency degree (GED); the average participant was 39 years old (standard deviation = 10). The sample was also racially/ethnically diverse, comprised of 40% Hispanic, 35% non-Hispanic White, and 17% Native American participants (others were African American, Asian, or unspecific race/ethnicity).

The researchers used sophisticated statistical analyses called hierarchical linear modeling:

- To examine the course of depression over 2 years, and if depression decreased, to investigate whether improved drinking outcomes were associated with this decrease;

- To examine the time-lagged effects of AA attendance on depression over 2 years (excluding 9-month assessment, where depression was not measured), controlling for formal treatment and drinking outcomes; in other words, they measured the unique cumulative effect of AA attendance at baseline on depression at 3 months, AA attendance at 3 months on depression at 6 months, AA attendance at 9 months on depression at 12 months, and so on; and

- To examine the time-lagged effects of religious/spiritual practices and AA step work on depression over 2 years, like in Aim 2, but also controlling for AA attendance.

They used another sophisticated analytic approach called bootstrapping to investigate if either the effects of:

- 3-month AA attendance

- 3-month religious/spiritual practices

- AA step work on depression at 24 months

were explained by drinking outcomes at 12 months, over and above the effects of baseline drinking and treatment attendance over time.

The analyses examining religious/spiritual practices and AA step work also controlled statistically for the effect of AA attendance. These are often referred to as tests of mediation.

Alcohol outcomes were abstinence, measured by percent days abstinent (PDA), drinking intensity, measured by drinks per drinking day (DDD). Religious/spiritual practices were measured with the Religious Background and Behaviors Scale (RBB).

For this study, authors used this scale to measure the frequency in the past 90 days of:

- a) thinking about God

- b) prayer

- c) meditation

- d) attending worship services

- e) reading/studying scripture or holy writing

- f) having had direct experiences of God

Step work was assessed with completion of what authors called “surrender” steps (steps 1-3; total possible = 3), “action” steps (steps 4-9; total possible = 6), and “maintenance” steps (steps 10-12; total possible = 3). See here for the list of AA’s 12 steps and discussion of each step.

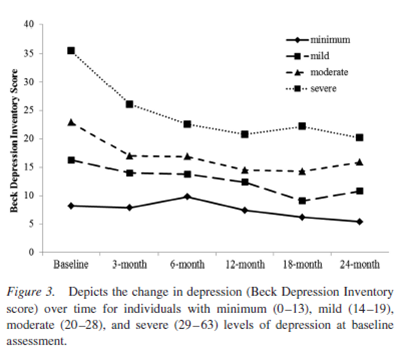

Depression was measured with the second edition of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), a 21-item self-report questionnaire (score range = 0-63). Participants entered the study with an average depression score of 20, indicating that study participants, on average, were suffering from moderate levels of depression.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

As hypothesized, participants’ depression decreased over time.

Drinking outcomes at each time point were related to depression in the expected directions. Specifically, lower levels of depression were related to greater abstinence and less intensive drinking.

Importantly, AA attendance was associated with reduced depression over time, even when controlling for the effects of drinking at the time depression was measured.

This effect of AA on depression was present for both participants with low/minimal depression and those with moderate/severe depression. More religious/spiritual practices were also related to reduced depression over time. Contrary to expectations, completing AA’s “action” steps were related to increased depression; neither of the other groups of steps were related to depression over time.

Regarding the mediation analyses that looked deeper into the effect of AA attendance on helping to reduce depression symptoms, this effect was found to be explained, in part, by increasing abstinence, but not by decreasing drinking intensity (in separate mediation models). See the figure below for a graphical depiction of this mediated effect. Neither religious/spiritual practices, nor any of the step work variables, however, were found to explain a significant percentage of this AA-depression effect.

This study helps contextualize two other studies that authors also mention:

- In one, Kelly et al. found that the effect of AA attendance on later drinking outcomes was explained, in part, by reducing depression in Project MATCH participants. However, this explanatory effect itself seemed to be explained by AA’s ability to increase abstinence. Consequently, the effect of AA on depression all but disappeared when earlier drinking was accounted for along with depression (see here). In other words, it remained plausible that reducing depression is part of the AA story only in so much as the decreased symptoms are a mental health benefit of reduced drinking.

- In the second, Worley et al., too, showed this pattern in a sample of patients with co-occurring alcohol use disorder and major depressive disorder. But in that case, however, the effect of AA on reduced drinking through reduced depression was still present even after accounting for drinking at the same time (see here).

So what can we conclude from these three results? It seems, on average, individuals with alcohol use disorders are likely to experience reduced depression as they increase their frequency of AA attendance.

Also, at least for those who are new to AA, or who have co-occurring major depressive disorder (that would require clinical attention even if the individual’s alcohol use disorder was in remission), attendance does indeed appear to be related to less depression, beyond the decrease that comes simply from giving up drinking. These participants may derive added benefit related to mood beyond abstinence. The reasons for this are as yet unclear. One possibility is that these individuals may select aspects of the AA program or fellowship that help them address this added depression burden (e.g., participating in social activities with other AA members).

The relationship between spiritual/religious practices and depression might be even more nuanced. There is a large body of literature suggesting individuals who are more religious are less depressed, and less likely to develop depression (see here). Thus the relationship between greater religious/spiritual practices and lower depression is perhaps not surprising.

Also, there are some studies that suggest AA attendance exerts its influence on improved drinking outcomes through increases in religious/spiritual practices (see here and here, for example). However, this explanatory effect may not hold up as well when other, more socially-grounded mechanisms, like modifying one’s social network, are considered at the same time (see here). This background role of spirituality/religiosity in early recovery may be especially true for individuals with lower initial addiction severity, such as young adults (see here, for example). In other words, the effect of religiosity/spirituality on enhanced abstinence and psychological and emotional well-being may be part of the AA story, but only for some.

Finally, as the study authors pointed out, the observed relationship between working on the “action” steps of AA (steps 4 through 9), and increased depression symptoms was unexpected. Because these “action” steps involve documentation and analysis of past behavior as it has related to alcohol addiction, it is possible that for some individuals, such step work might have uncovered painful feelings. These emotional processes may have been responsible for the observed increase in depression.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

Prior studies have shown that about 50% of individuals who present to substance use disorder (SUD) treatment also have depressive symptoms & 20% have a current depressive disorder. Sometimes depressive symptoms can be caused directly by the effect of heavy alcohol use (a depressant drug) on the central nervous system.

Consequently, when people stop drinking or cut down substantially, these depression symptoms can often be reduced. For some, however, depressive symptoms will persist even after reducing or quitting drinking.

Not only is depression thought to trigger craving and influence relapse risk, but depressive symptoms can be quite debilitating in their own right, depending on their level of severity.

Findings from this study are important, as they provide insight into whether participation in AA can uniquely reduce depressive symptoms among attendees, separate from its ability to promote increased abstinence rates.

This research suggests that a clinician can refer patients to AA that present with depressive symptoms in addition to alcohol use disorder, as it is likely to help enhance recovery. These gains may occur both for alcohol abstinence as well as other aspects of well-being, such as reduced depressive symptoms.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Despite the Religious Background and Behavior Scale’s status as a well-validated and popular measure, its assessment of more traditional religious activities (e.g., attending worship services) may not map directly onto 12-step MHO literature’s conception of “God” as a “God of one’s own understanding.” It would be interesting to see if a more comprehensive measure of spiritual experience (i.e., also measuring gratitude and selflessness), such as the Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale, would indeed explain the relationship between AA attendance and reduced depression.

- Also, both spirituality/religiosity and step work were measured at 3 months in the mediation models. The development of spirituality to any measurable degree, and the time/effort needed to complete at least the first several steps often can take people many months. Three months may not have been a sufficient amount of time to capture changes in these important variables.

- Other limitations include the study’s naturalistic design, as is typically the case in studies of community-based 12-step MHO attendance. Specifically, the effects of reduced depression cannot be attributed entirely to AA attendance despite the researchers’ rigorous control for other factors that might have contributed to reduced depression (e.g., formal treatment engagement).

NEXT STEPS

There are several mechanisms of action known to aid enhanced recovery in 12-step MHOs that might reasonably help reduce depression but were not examined here. For example, future studies might investigate whether the effect of AA on depression is explained by forming new social-recovery relationships (e.g., with a sponsor) and engaging in activities (e.g., with other recovering individuals) facilitated by the rich 12-step MHO milieu.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: For depression & alcohol use disorder, attending AA may help not only reduce your relapse risk but also your feelings of depression. This benefit may also be true for other types of mutual-help groups, though more research is needed on 12-step groups other than AA as well as other non-12-step mutual-help groups. In addition, more research is needed to determine the specific types of activities that might help reduce your depression apart from simply attending meetings.

- For scientists: This rigorous, well-conducted study made a significant contribution to the science on benefits of 12-step mutual-help organizations. Mediation analyses showed that the effect of AA attendance on reduced depression may be explained, in part, by reductions in drinking. However, there appears to be an independent effect of attendance on depression, rather than a straightforward mental health benefit of reduced drinking. Follow-up studies might illuminate what types of 12-step activities, in addition to attendance, explain its effect. Given the null results here, step work appears to be an unlikely source, but needs further investigation.

- For policy makers: This study showed that 12-step mutual help attendance might help individuals feel less depressed in addition to its benefit on alcohol outcomes established by prior scientific research. Because depression itself confers a large burden of disability and lost productivity nationally and internationally, groups like AA may help to reduce the broader psychiatric burden of disease beyond its robust association with reductions in drinking. Strongly consider funding research that continues to examine the recovery benefits of 12-step participation beyond abstinence.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study suggests it is reasonable to refer to AA patients that present with depressive symptoms in addition to alcohol use disorder. It is also reasonable to anticipate this will help enhance the patient’s recovery, both with respect to alcohol abstinence and other aspects of well-being, such as reduced depressive symptoms.

CITATIONS

Wilcox, C. E., Pearson, M. R., & Tonigan, J. S. (2015). Effects of long-term AA attendance and spirituality on the course of depressive symptoms in individuals with alcohol use disorder. Psychol Addict Behav, 29(2), 382-391. doi: 10.1037/adb0000053