l

Clinical observation and some preliminary studies suggest the GLP-1 medication semaglutide—better known by brand names like Ozempic, Mounjaro, and Wegovy—can reduce cravings and help individuals with alcohol use disorder reduce or stop drinking. Though the mechanisms through which this drug might influence alcohol craving and consumption are not known, in theory semaglutide’s inhibition of the appetitive centers in the brain could lead to reduced cravings and appetite for things other than food, like alcohol and other drugs.

To date, much of the research on the effects of semaglutide on alcohol consumption has involved animal studies, or observational studies with humans. Though findings have been promising, there is a need for gold-standard randomized controlled trials to inform clinical decision making and practice.

In this study, the researchers conducted one of the first randomized controlled trials of semaglutide for people with alcohol use disorder, examining the effects of this medication on alcohol craving and consumption in a non-treatment-seeking sample. By studying semaglutide’s effects in a non-treatment-seeking sample, the researchers were able to explore how this drug directly influences alcohol craving and consumption without potential confounders like treatment and recovery motivation.

This was a randomized controlled trial of semaglutide for alcohol use disorder that included 48 non-treatment-seeking adults with alcohol use disorder, to test semaglutide’s effects on alcohol craving and consumption.

Participants were randomized to receive either 9 weeks of semaglutide or placebo. Semaglutide was administered weekly at the relatively lower doses of 0.25mg/week for the first 4 weeks, and then at 0.5mg/week during weeks 5-8. To test the safety of this medication with this population, participants received a higher final dose of 1.0mg at week 9, assuming they had tolerated the lower doses. Participants with significant side effects at the lower doses were held at 0.5mg at week 9 dosing. Participants randomized to the placebo group received sham subcutaneous injections. As an important guard against experimenter effects biasing results, participants, investigators, and outcome assessors were all not told participants’ experimental condition (i.e., they were ”kept blind” to study condition).

Primary study outcomes included:

1) Volume of alcohol consumed, and participants’ blood alcohol levels during a laboratory-based alcohol self-administration paradigm at baseline and end of treatment in which participants were provided with their preferred alcoholic drink and brand and could elect to delay drinking for up to 50 minutes for monetary payments. They were then instructed to consume at their preferred pace to achieve the preferred effect over the following 2 hours. Half of the participants did not want to drink alcohol during the trial and thus did not complete the self-administration task, excluding them from only these analyses.

2) Average weekly craving, average drinks per day, drinks per drinking day, number of heavy drinking days, and number of drinking vs abstinent days measured with daily self-report logs.

The study sample was 71% female, mostly White with a mean age of 39.9 years. At baseline, they had an average of 4 DSM-5 alcohol use disorder symptoms (consistent with moderate severity), consumed alcohol 20/28 days and 9/28 days with heavy drinking (4+ for women and 5+ for men each day).

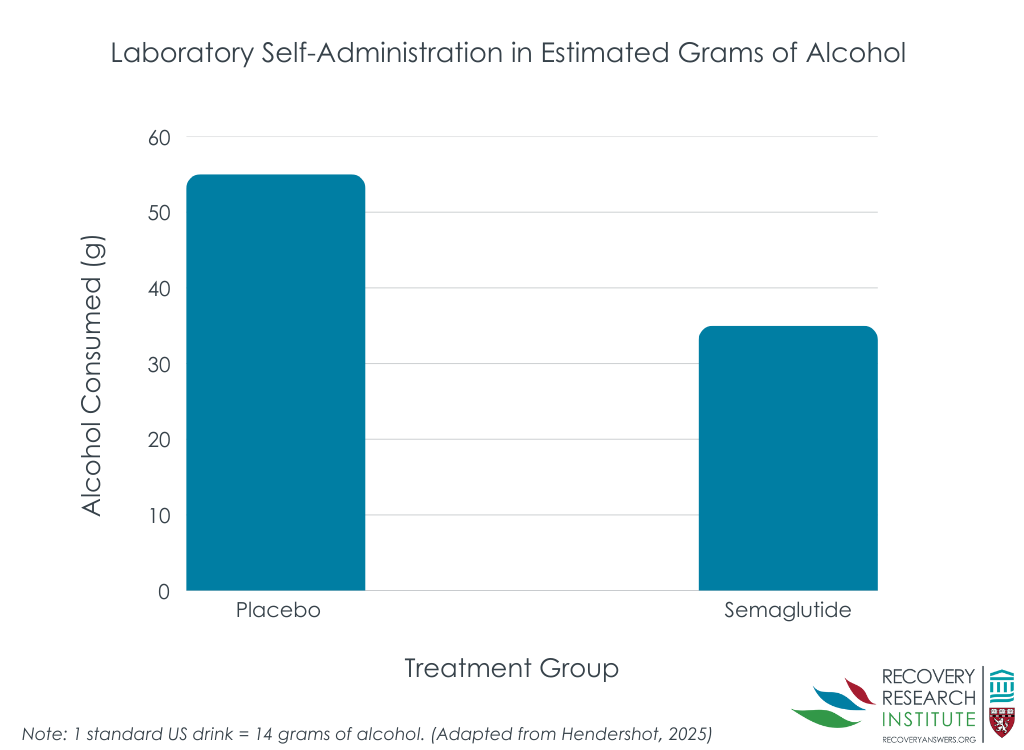

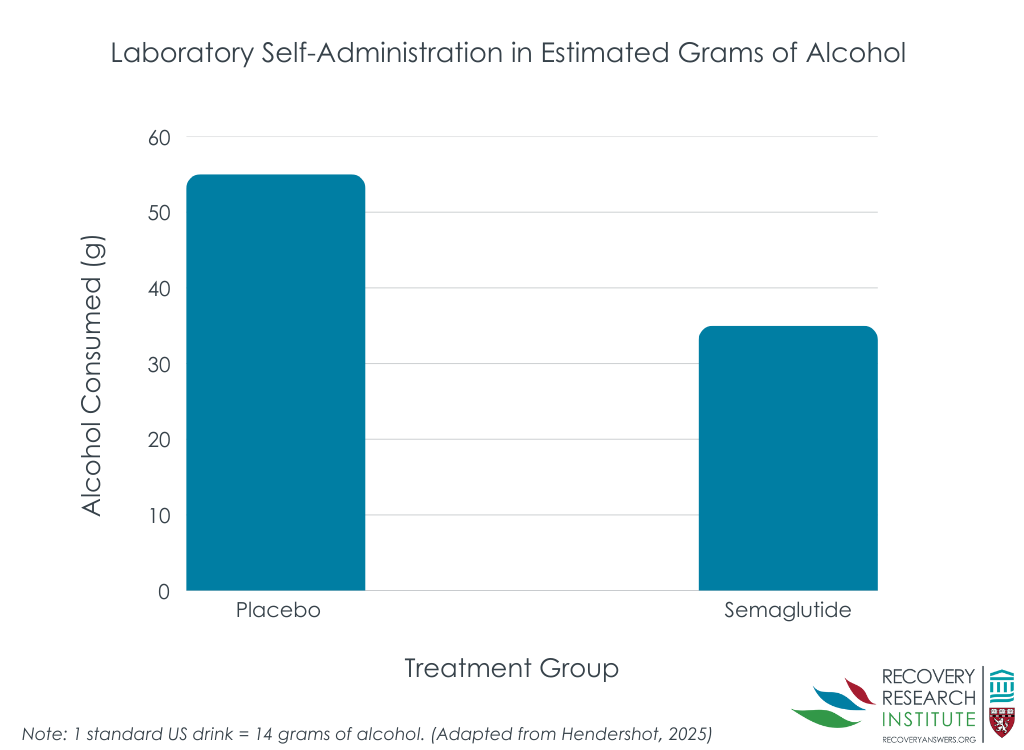

Semaglutide was associated with reduced alcohol consumption and blood alcohol levels during the laboratory drinking task

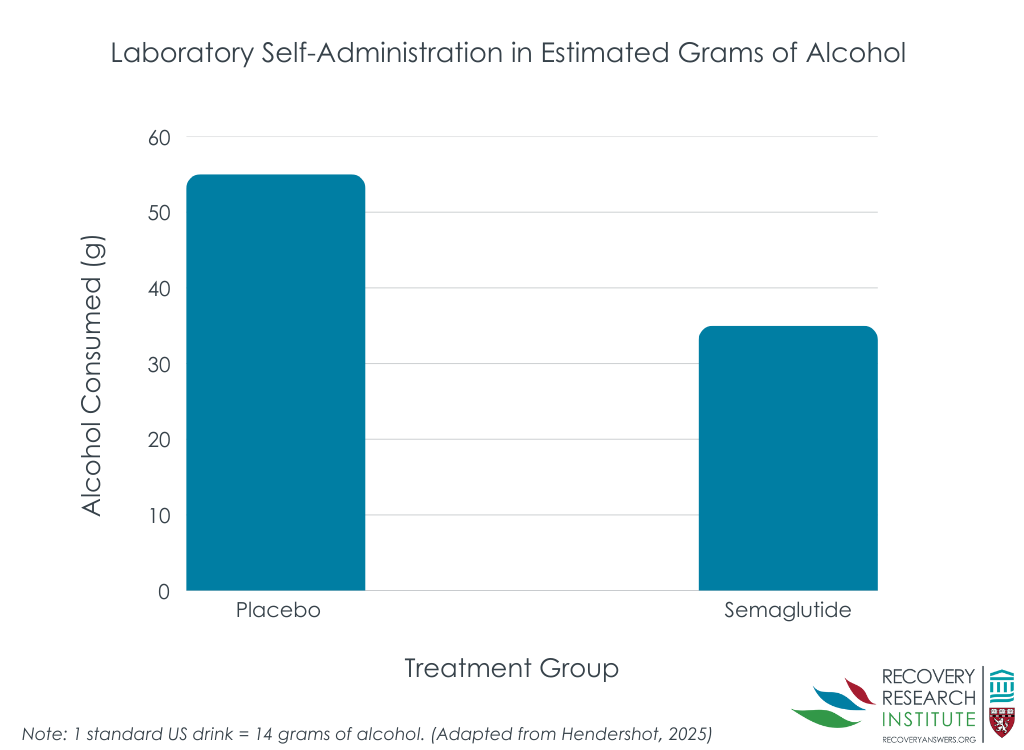

Participants receiving semaglutide drank less (bar graph below) and achieved lower blood alcohol levels during the end of treatment alcohol self-administration paradigm. This was after accounting for participants’ alcohol consumption and blood alcohol levels during the baseline alcohol self-administration task. Effect sizes differences were medium to large. However, medication condition was not associated with time to initiating drinking in the paradigm.

Semaglutide was also associated with reduced craving and drinks per day

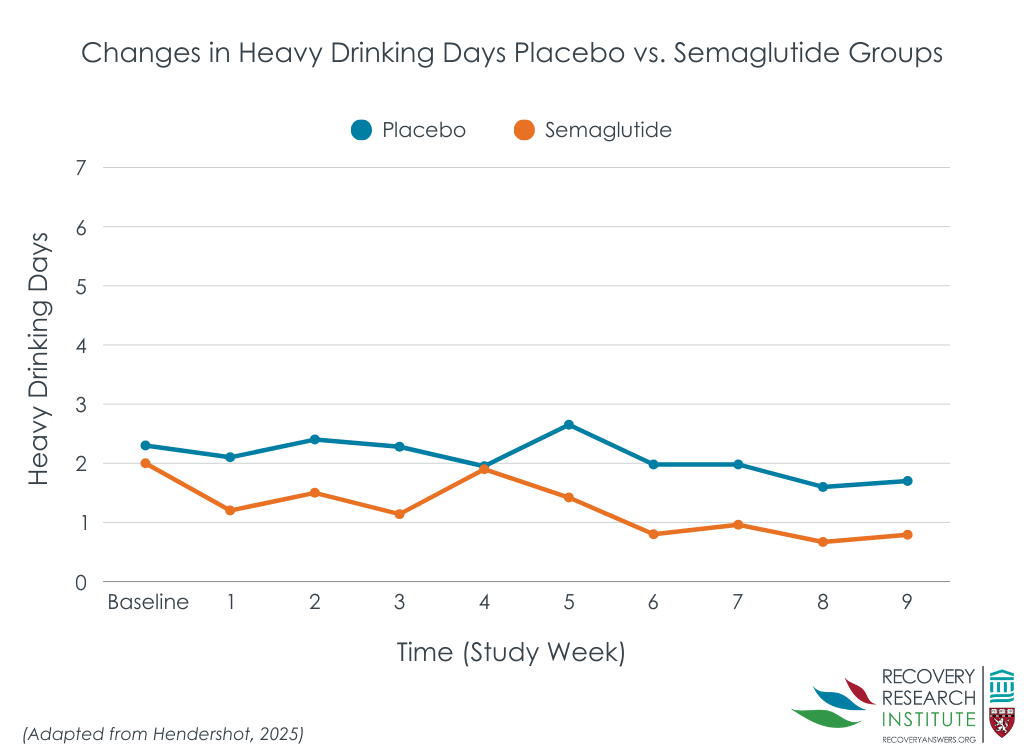

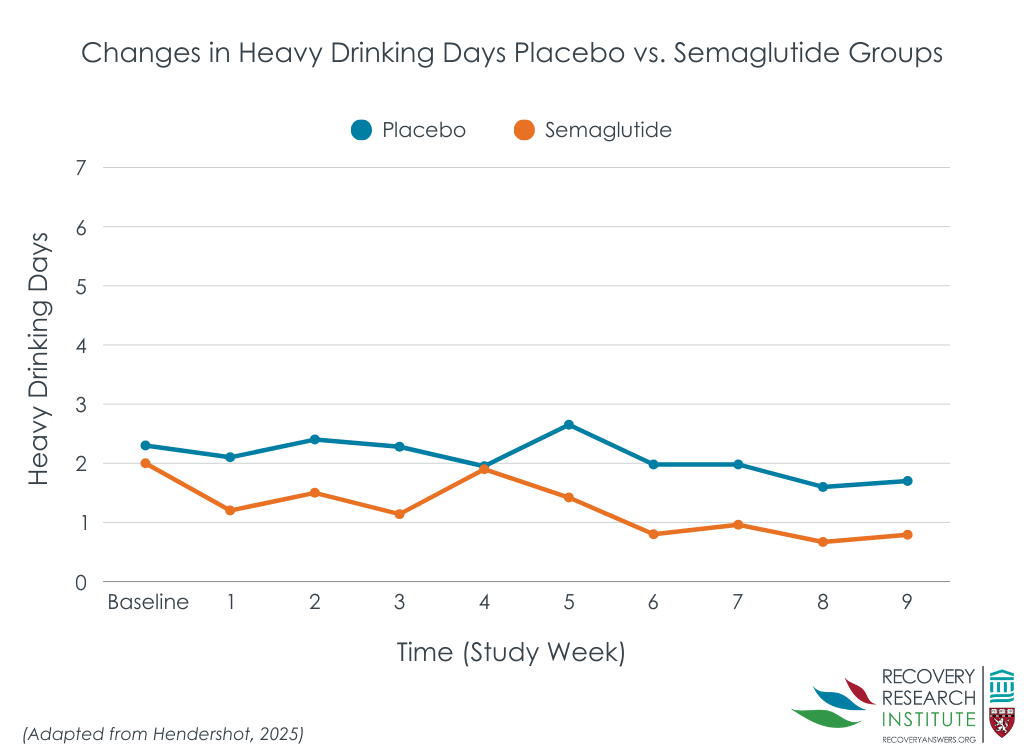

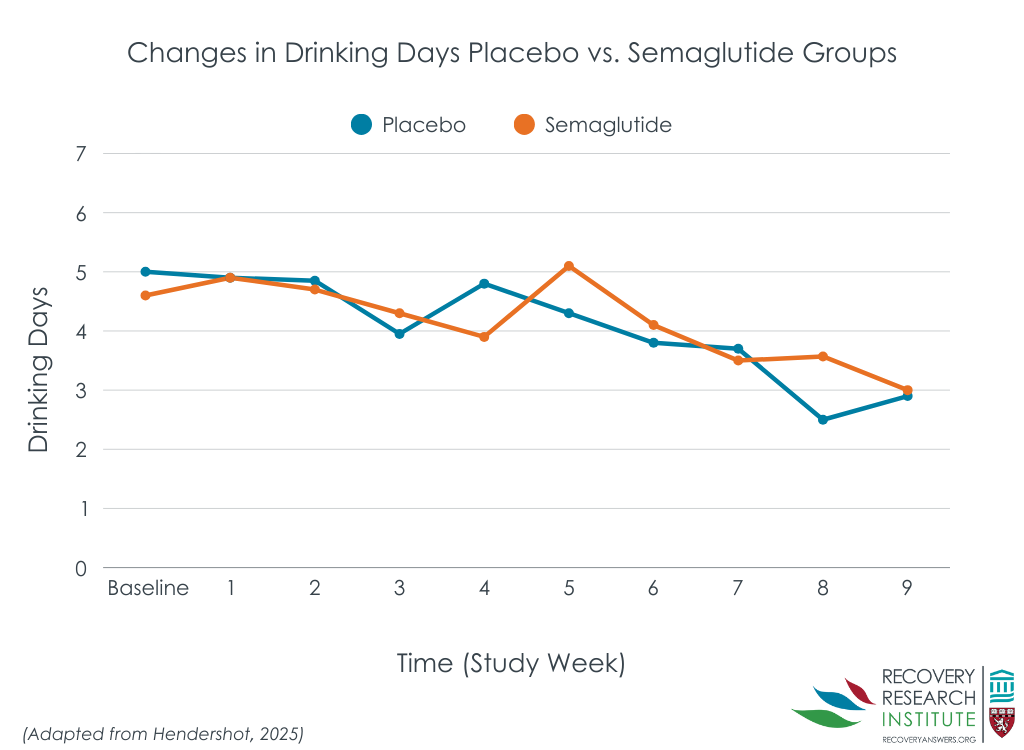

Data from participants’ daily logs indicated that those receiving semaglutide had less average alcohol craving each week (small effect size), and on average drank less drinks per drinking day while also having greater reductions in heavy drinking days over time (large effect sizes; line graph below).

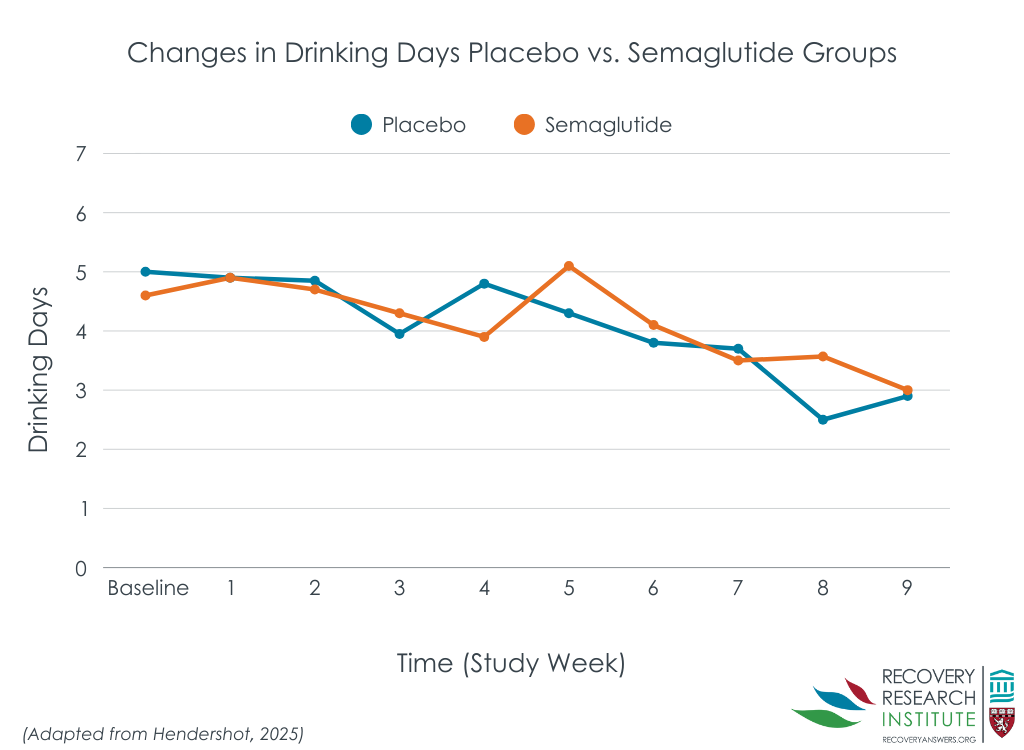

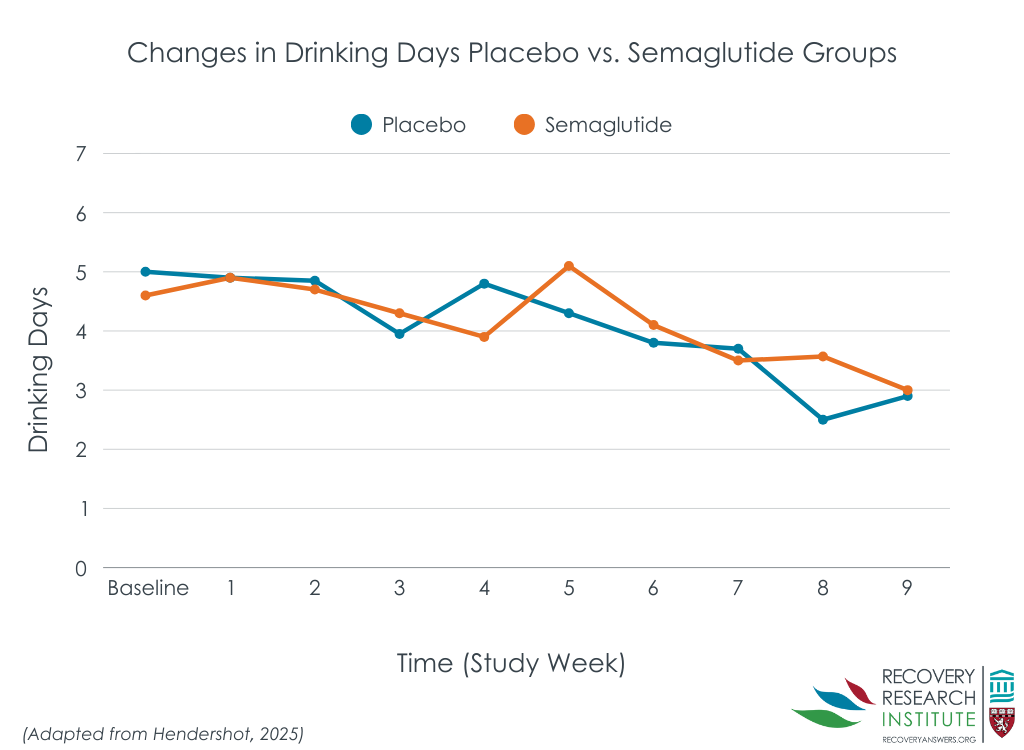

However, semaglutide and placebo had similar number of drinks per calendar day, and number of drinking days over the 9-week study period (line graph below).

Some safety considerations were noted

Participants in the semaglutide group lost on average 5% of their body weight. This did not present a risk in the researchers’ sample because they excluded people with body-mass indices (BMIs) lower than 23 (the World Health Organization considers BMIs 18.5 – 24.9 normal), and most study participants had a BMI of 30 or more (classified as obese). For people of average and below average weight, however, this weight loss could be problematic.

Consistent with the known effects and common side effects of semaglutide, more participants receiving active medication reported decreased appetite as well as increased nausea and constipation. However, a similar number of participants in each group endorsed other side effects like dizziness, insomnia, nervousness/anxiety, and vomiting. No notable medication side effects were found for average blood glucose levels over the past 2-3 months (hemoglobin A1c), blood pressure, or depression.

Although the sample size was small with only 48 total participants randomized across the two treatment conditions, the randomized, double-blinded, experimental design provides some compelling preliminary evidence that semaglutide might reduce alcohol craving and the amount of alcohol consumed on drinking days in people with alcohol use disorder not actively seeking treatment. This is exciting because while presently there are already 3 FDA approved medications for alcohol use disorder, their effects are modest. It is also important to find different medication types that may have an effect given the complexity of alcohol use disorder as well as patient preference.

In terms of its effects, it appears to impact drinking in ways (though not necessarily mechanisms) similar to naltrexone (FDA-approved) and topiramate (prescribed off label for alcohol use disorder), which have a greater effect in reducing intensity of drinking on drinking days relative to their effects on whether someone drinks at all (i.e., abstinent days) – although all of them do increase abstinent days to some degree on average). Semaglutide could ultimately be a valuable pharmacological alternative or add-on to these medications, however, more studies are needed to determine the efficacy of this drug, as well as its safety in people with average and below average BMI for whom weight loss could cause medical problems. Future studies will also need to assess the effects of semaglutide on alcohol craving and consumption at higher medication doses and with people with severe alcohol use disorder.

Semaglutide may help some individuals reduce their alcohol use on days where they have at least 1 drink – while also reducing cravings for alcohol. However, this was a small study of 48 individuals and more research is needed to inform clinical decision making and treatment guidelines.

Hendershot, C. S., Bremmer, M. P., Paladino, M. B., Kostantinis, G., Gilmore, T. A., Sullivan, N. R., Tow, A. C., Dermody, S. S., Prince, M. A., Jordan, R., McKee, S. A., Fletcher, P. J., Claus, E. D., & Klein, K. R. (2025). Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with alcohol use disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.4789

l

Clinical observation and some preliminary studies suggest the GLP-1 medication semaglutide—better known by brand names like Ozempic, Mounjaro, and Wegovy—can reduce cravings and help individuals with alcohol use disorder reduce or stop drinking. Though the mechanisms through which this drug might influence alcohol craving and consumption are not known, in theory semaglutide’s inhibition of the appetitive centers in the brain could lead to reduced cravings and appetite for things other than food, like alcohol and other drugs.

To date, much of the research on the effects of semaglutide on alcohol consumption has involved animal studies, or observational studies with humans. Though findings have been promising, there is a need for gold-standard randomized controlled trials to inform clinical decision making and practice.

In this study, the researchers conducted one of the first randomized controlled trials of semaglutide for people with alcohol use disorder, examining the effects of this medication on alcohol craving and consumption in a non-treatment-seeking sample. By studying semaglutide’s effects in a non-treatment-seeking sample, the researchers were able to explore how this drug directly influences alcohol craving and consumption without potential confounders like treatment and recovery motivation.

This was a randomized controlled trial of semaglutide for alcohol use disorder that included 48 non-treatment-seeking adults with alcohol use disorder, to test semaglutide’s effects on alcohol craving and consumption.

Participants were randomized to receive either 9 weeks of semaglutide or placebo. Semaglutide was administered weekly at the relatively lower doses of 0.25mg/week for the first 4 weeks, and then at 0.5mg/week during weeks 5-8. To test the safety of this medication with this population, participants received a higher final dose of 1.0mg at week 9, assuming they had tolerated the lower doses. Participants with significant side effects at the lower doses were held at 0.5mg at week 9 dosing. Participants randomized to the placebo group received sham subcutaneous injections. As an important guard against experimenter effects biasing results, participants, investigators, and outcome assessors were all not told participants’ experimental condition (i.e., they were ”kept blind” to study condition).

Primary study outcomes included:

1) Volume of alcohol consumed, and participants’ blood alcohol levels during a laboratory-based alcohol self-administration paradigm at baseline and end of treatment in which participants were provided with their preferred alcoholic drink and brand and could elect to delay drinking for up to 50 minutes for monetary payments. They were then instructed to consume at their preferred pace to achieve the preferred effect over the following 2 hours. Half of the participants did not want to drink alcohol during the trial and thus did not complete the self-administration task, excluding them from only these analyses.

2) Average weekly craving, average drinks per day, drinks per drinking day, number of heavy drinking days, and number of drinking vs abstinent days measured with daily self-report logs.

The study sample was 71% female, mostly White with a mean age of 39.9 years. At baseline, they had an average of 4 DSM-5 alcohol use disorder symptoms (consistent with moderate severity), consumed alcohol 20/28 days and 9/28 days with heavy drinking (4+ for women and 5+ for men each day).

Semaglutide was associated with reduced alcohol consumption and blood alcohol levels during the laboratory drinking task

Participants receiving semaglutide drank less (bar graph below) and achieved lower blood alcohol levels during the end of treatment alcohol self-administration paradigm. This was after accounting for participants’ alcohol consumption and blood alcohol levels during the baseline alcohol self-administration task. Effect sizes differences were medium to large. However, medication condition was not associated with time to initiating drinking in the paradigm.

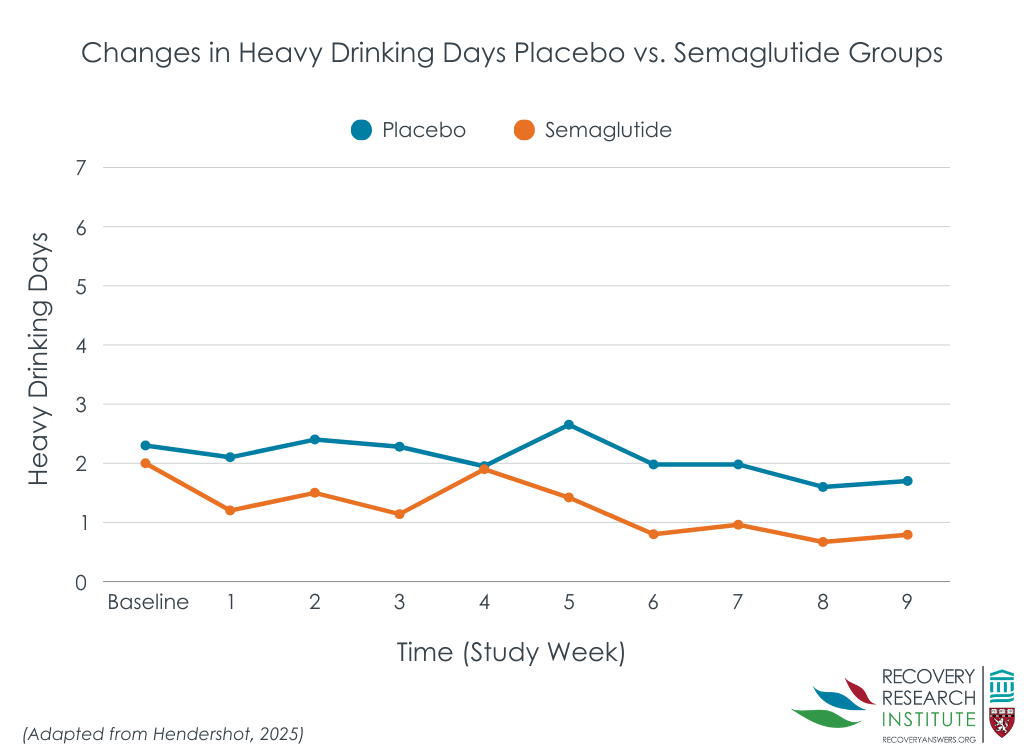

Semaglutide was also associated with reduced craving and drinks per day

Data from participants’ daily logs indicated that those receiving semaglutide had less average alcohol craving each week (small effect size), and on average drank less drinks per drinking day while also having greater reductions in heavy drinking days over time (large effect sizes; line graph below).

However, semaglutide and placebo had similar number of drinks per calendar day, and number of drinking days over the 9-week study period (line graph below).

Some safety considerations were noted

Participants in the semaglutide group lost on average 5% of their body weight. This did not present a risk in the researchers’ sample because they excluded people with body-mass indices (BMIs) lower than 23 (the World Health Organization considers BMIs 18.5 – 24.9 normal), and most study participants had a BMI of 30 or more (classified as obese). For people of average and below average weight, however, this weight loss could be problematic.

Consistent with the known effects and common side effects of semaglutide, more participants receiving active medication reported decreased appetite as well as increased nausea and constipation. However, a similar number of participants in each group endorsed other side effects like dizziness, insomnia, nervousness/anxiety, and vomiting. No notable medication side effects were found for average blood glucose levels over the past 2-3 months (hemoglobin A1c), blood pressure, or depression.

Although the sample size was small with only 48 total participants randomized across the two treatment conditions, the randomized, double-blinded, experimental design provides some compelling preliminary evidence that semaglutide might reduce alcohol craving and the amount of alcohol consumed on drinking days in people with alcohol use disorder not actively seeking treatment. This is exciting because while presently there are already 3 FDA approved medications for alcohol use disorder, their effects are modest. It is also important to find different medication types that may have an effect given the complexity of alcohol use disorder as well as patient preference.

In terms of its effects, it appears to impact drinking in ways (though not necessarily mechanisms) similar to naltrexone (FDA-approved) and topiramate (prescribed off label for alcohol use disorder), which have a greater effect in reducing intensity of drinking on drinking days relative to their effects on whether someone drinks at all (i.e., abstinent days) – although all of them do increase abstinent days to some degree on average). Semaglutide could ultimately be a valuable pharmacological alternative or add-on to these medications, however, more studies are needed to determine the efficacy of this drug, as well as its safety in people with average and below average BMI for whom weight loss could cause medical problems. Future studies will also need to assess the effects of semaglutide on alcohol craving and consumption at higher medication doses and with people with severe alcohol use disorder.

Semaglutide may help some individuals reduce their alcohol use on days where they have at least 1 drink – while also reducing cravings for alcohol. However, this was a small study of 48 individuals and more research is needed to inform clinical decision making and treatment guidelines.

Hendershot, C. S., Bremmer, M. P., Paladino, M. B., Kostantinis, G., Gilmore, T. A., Sullivan, N. R., Tow, A. C., Dermody, S. S., Prince, M. A., Jordan, R., McKee, S. A., Fletcher, P. J., Claus, E. D., & Klein, K. R. (2025). Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with alcohol use disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.4789

l

Clinical observation and some preliminary studies suggest the GLP-1 medication semaglutide—better known by brand names like Ozempic, Mounjaro, and Wegovy—can reduce cravings and help individuals with alcohol use disorder reduce or stop drinking. Though the mechanisms through which this drug might influence alcohol craving and consumption are not known, in theory semaglutide’s inhibition of the appetitive centers in the brain could lead to reduced cravings and appetite for things other than food, like alcohol and other drugs.

To date, much of the research on the effects of semaglutide on alcohol consumption has involved animal studies, or observational studies with humans. Though findings have been promising, there is a need for gold-standard randomized controlled trials to inform clinical decision making and practice.

In this study, the researchers conducted one of the first randomized controlled trials of semaglutide for people with alcohol use disorder, examining the effects of this medication on alcohol craving and consumption in a non-treatment-seeking sample. By studying semaglutide’s effects in a non-treatment-seeking sample, the researchers were able to explore how this drug directly influences alcohol craving and consumption without potential confounders like treatment and recovery motivation.

This was a randomized controlled trial of semaglutide for alcohol use disorder that included 48 non-treatment-seeking adults with alcohol use disorder, to test semaglutide’s effects on alcohol craving and consumption.

Participants were randomized to receive either 9 weeks of semaglutide or placebo. Semaglutide was administered weekly at the relatively lower doses of 0.25mg/week for the first 4 weeks, and then at 0.5mg/week during weeks 5-8. To test the safety of this medication with this population, participants received a higher final dose of 1.0mg at week 9, assuming they had tolerated the lower doses. Participants with significant side effects at the lower doses were held at 0.5mg at week 9 dosing. Participants randomized to the placebo group received sham subcutaneous injections. As an important guard against experimenter effects biasing results, participants, investigators, and outcome assessors were all not told participants’ experimental condition (i.e., they were ”kept blind” to study condition).

Primary study outcomes included:

1) Volume of alcohol consumed, and participants’ blood alcohol levels during a laboratory-based alcohol self-administration paradigm at baseline and end of treatment in which participants were provided with their preferred alcoholic drink and brand and could elect to delay drinking for up to 50 minutes for monetary payments. They were then instructed to consume at their preferred pace to achieve the preferred effect over the following 2 hours. Half of the participants did not want to drink alcohol during the trial and thus did not complete the self-administration task, excluding them from only these analyses.

2) Average weekly craving, average drinks per day, drinks per drinking day, number of heavy drinking days, and number of drinking vs abstinent days measured with daily self-report logs.

The study sample was 71% female, mostly White with a mean age of 39.9 years. At baseline, they had an average of 4 DSM-5 alcohol use disorder symptoms (consistent with moderate severity), consumed alcohol 20/28 days and 9/28 days with heavy drinking (4+ for women and 5+ for men each day).

Semaglutide was associated with reduced alcohol consumption and blood alcohol levels during the laboratory drinking task

Participants receiving semaglutide drank less (bar graph below) and achieved lower blood alcohol levels during the end of treatment alcohol self-administration paradigm. This was after accounting for participants’ alcohol consumption and blood alcohol levels during the baseline alcohol self-administration task. Effect sizes differences were medium to large. However, medication condition was not associated with time to initiating drinking in the paradigm.

Semaglutide was also associated with reduced craving and drinks per day

Data from participants’ daily logs indicated that those receiving semaglutide had less average alcohol craving each week (small effect size), and on average drank less drinks per drinking day while also having greater reductions in heavy drinking days over time (large effect sizes; line graph below).

However, semaglutide and placebo had similar number of drinks per calendar day, and number of drinking days over the 9-week study period (line graph below).

Some safety considerations were noted

Participants in the semaglutide group lost on average 5% of their body weight. This did not present a risk in the researchers’ sample because they excluded people with body-mass indices (BMIs) lower than 23 (the World Health Organization considers BMIs 18.5 – 24.9 normal), and most study participants had a BMI of 30 or more (classified as obese). For people of average and below average weight, however, this weight loss could be problematic.

Consistent with the known effects and common side effects of semaglutide, more participants receiving active medication reported decreased appetite as well as increased nausea and constipation. However, a similar number of participants in each group endorsed other side effects like dizziness, insomnia, nervousness/anxiety, and vomiting. No notable medication side effects were found for average blood glucose levels over the past 2-3 months (hemoglobin A1c), blood pressure, or depression.

Although the sample size was small with only 48 total participants randomized across the two treatment conditions, the randomized, double-blinded, experimental design provides some compelling preliminary evidence that semaglutide might reduce alcohol craving and the amount of alcohol consumed on drinking days in people with alcohol use disorder not actively seeking treatment. This is exciting because while presently there are already 3 FDA approved medications for alcohol use disorder, their effects are modest. It is also important to find different medication types that may have an effect given the complexity of alcohol use disorder as well as patient preference.

In terms of its effects, it appears to impact drinking in ways (though not necessarily mechanisms) similar to naltrexone (FDA-approved) and topiramate (prescribed off label for alcohol use disorder), which have a greater effect in reducing intensity of drinking on drinking days relative to their effects on whether someone drinks at all (i.e., abstinent days) – although all of them do increase abstinent days to some degree on average). Semaglutide could ultimately be a valuable pharmacological alternative or add-on to these medications, however, more studies are needed to determine the efficacy of this drug, as well as its safety in people with average and below average BMI for whom weight loss could cause medical problems. Future studies will also need to assess the effects of semaglutide on alcohol craving and consumption at higher medication doses and with people with severe alcohol use disorder.

Semaglutide may help some individuals reduce their alcohol use on days where they have at least 1 drink – while also reducing cravings for alcohol. However, this was a small study of 48 individuals and more research is needed to inform clinical decision making and treatment guidelines.

Hendershot, C. S., Bremmer, M. P., Paladino, M. B., Kostantinis, G., Gilmore, T. A., Sullivan, N. R., Tow, A. C., Dermody, S. S., Prince, M. A., Jordan, R., McKee, S. A., Fletcher, P. J., Claus, E. D., & Klein, K. R. (2025). Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with alcohol use disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.4789