Substance use disorder recovery – there’s an app for that… but who uses it and who benefits?

Social network sites that support addiction recovery—platforms that work in ways similar to Facebook and Twitter but are dedicated to helping individuals with substance use problems—are growing in popularity. Most of these kinds of digital recovery support services, however, have yet to be evaluated and little is known about their mechanisms – how exactly they might help. To begin to address this gap in the clinical literature, the authors conducted an analysis of Sober Grid, a popular substance use disorder (SUD) recovery smartphone application.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Recovery-specific social network sites—platforms that work in ways similar to Facebook and Twitter but are dedicated to helping individuals with substance use problems—are increasingly being utilized by individuals seeking to augment their existing treatments or find novel recovery pathways. These sites, which may be accessed by website, smartphone application (i.e., app), or both, have a lot of potential, as theoretically they can replicate many aspects of supportive recovery communities (e.g., ease of access, and low/no cost) like Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, SMART, and Refuge Recovery, and they allow end-users to receive and share recovery-related information. Few studies, however, have assessed this class of apps, either in terms of their usership, or their functionality.

In this collaboration between academic researchers and staff from the recovery-specific social network site, Sober Grid, the authors described participants and their activities using this free smartphone-based app designed to support individuals recovery from substance use disorder.

Like the more ubiquitous general social network sites such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, features of Sober Grid include text-based and photo-based status sharing, user check-ins, a geolocation “grid” that allows end-users to find others in recovery near their location, person to person connections (unilateral where 1 person follows another without being followed back, or bilateral, where individuals follow each other), alumni group pages (for graduates of specific treatment facilities), and a ‘burning desire’ feature that allows users to immediately reach out for help from others in the community. This app is also similar to other social network sites in that it allows individuals to share statuses, comment on shared statuses, and direct message one another.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This observational study was a retrospective analysis of app usage data from 1,273 of the most frequent Sober Grid end-users collected from the app’s launch in April 2015 through January 2018. All measures used in the analysis were demographic variables collected upon sign-up or through day-to-day activities logged by the app. Study inclusion criteria included, 1) reporting gender and age at sign-up, 2) being between 18 and 80 years of age, and 3) having at least 30 days between account creation and last login, meaning brand new users were excluded. Additionally, in order to ensure only active users of the app were included in the analysis, the authors created a ‘login index’ capturing frequency of logins (defined as the number of total logins divided by the number of days between account creation and last login). Of note, only those in the top third of login frequency were included in the analysis. As a group, these users had a range of logins from 1 to 1,572, with an average total login count of 12.5 and an average account age of 396 days. Of the original sample (n= 102,242 unique users), 3,819 met inclusion criteria. After excluding individuals not regularly using the app (i.e., the bottom two-thirds of logins), 1,273 individuals were left, making up participants for the current study.

Methods for assessing recovery-related characteristics:

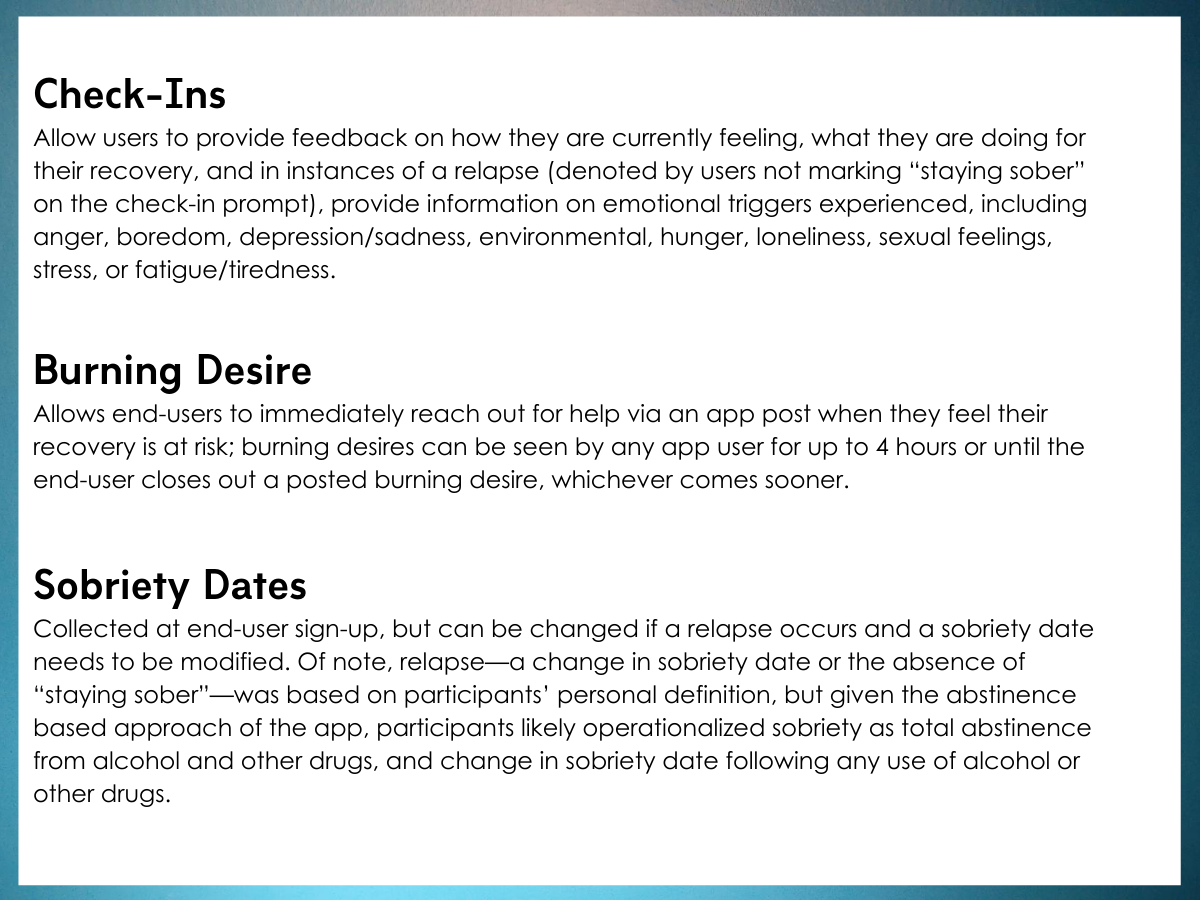

The authors assessed the use of 3 app activities and the resulting data as participant recovery related characteristics for this study. Activities included, 1) check-ins, 2) use of the burning desire feature, and 3) sobriety date changes.

“Check-ins” on the app allow end-users to provide feedback on how they are feeling, recovery activities, and relapse episodes as well as to share information about emotional triggers like depression/sadness, stress, anger, boredom, hunger, loneliness, sexual feelings, or tiredness. With the “burning desire” feature, end-users can reach out for help via an app post when they feel at risk for relapse. These posts can be seen by any app user for up to 4 hours or until the end-user closes out a posted burning desire. “Sobriety dates” are collected at end-user sign-up, but can be changed if a relapse occurs and a sobriety date needs to be modified. Of note, relapse—a change in sobriety date or the absence of “staying sober”—was based on participants’ personal definition, but given the abstinence-based approach of the app, participants likely operationalized sobriety as total abstinence from alcohol and other drugs, and change in sobriety date following any use of alcohol or other drugs.

Figure 1.

From the sobriety date change activity, the authors defined 3 variables, 1) recovery length, 2) sobriety length, and 3) relapse (i.e., sobriety date change). Recovery length was defined as the entire period someone has been engaged in a recovery process—including instances of alcohol or other drug—while sobriety length was defined as the most recent length of time an individual has been continuously abstinent. Relapse was calculated as the number of times a user changed their sobriety date.

In terms of participants, just under two-thirds were men (62.3%) and the average age was 39.0 years. Authors broke down age into the following 3 categories: 40.1% “Millennials” ages 18-35, 48.8% “Generation X” ages 36-52, and 11.2% “Baby Boomers” ages 53 and older.

Methods for assessing recovery participation:

The authors defined 2 variable types reflecting recovery participation and engagement, 1) connections, and 2) activity. Connections on Sober Grid are unidirectional. Following a Twitter connection framework, following another user does not imply that you are automatically followed back, but if this does occur, a bidirectional connection is formed. The authors summed the number of unidirectional and bidirectional connections for each user. They also summed the total number of connections to alumni support groups (private group pages for various addiction treatment and aftercare programs). Several user activities were defined including, posts, comments, likes, chats, check-ins, and burning desires.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Sobriety length and number of relapses differed by generation.

End-users had average lengths of recovery of 265.9 days and an average 195.6 days of sobriety length. In the final sample (n= 1,273), participants self-reported 236 relapses via check-in (average of 0.3 per person), while relapses inferred from sobriety date changes were 3,307 (average of 4.4 per person). Of those reporting a relapse via check-in and an accompanying emotional trigger (n= 584), stress (19.5%), depression/sadness (17.3%), environment (15.1%), and loneliness (12.0%) were reported most often.

After statistically controlling for participant demographics, sobriety length was found to be associated with generation, number of unilateral connections, and number of check-ins. Specifically, the older Baby Boomers were more likely to have longer sobriety lengths compared to Millennials (37 days longer), users with more unilateral connections were more likely to have longer sobriety lengths (+0.2 days for each additional unilateral connection), and greater use of the check-in feature was associated with shorter sobriety lengths (0.2 fewer abstinent days for each additional check-in).

Additionally, after statistically controlling for user demographics, number of relapses (indicated by total number of sobriety date changes) was found to be associated with generation and number of check-ins. Baby Boomers were more likely to have a lower number of relapses compared to Millennials (Baby Boomers had 0.3 less relapses), and users that used the check-in feature more were more likely to have a greater number of relapses (0.1 more relapses for each additional check-in).

App usage characteristics differed by generation, but in an unexpected way.

Among all individuals in the final sample (n= 1,273), there were 33,441 unilateral (average per person = 26.3), 13,837 bilateral (average per person = 10.9), and 458 alumni support group (average per person = 0.4) connections. Users generated 120,435 unique posts (average per person = 94.6), 507,631 comments (average per person = 398.8), 1,617,124 likes (average per person = 1,270.3), 12,964 check-ins (average per person = 10.2) – 208 of which were with triggers, 593,082 chats (average per person = 465.9), and 95 burning desires (average per person = 0.1).

Figure 2.

Differences among generations for unilateral connections, bilateral connections, posts, comments, check-ins, and likes were also observed, such that Millennials had less unilateral connections on average compared to both Generation X’ers and Baby Boomers, as well as fewer bilateral connections on average compared to Generation X’ers. For activity, Millennials also had the least number of posts, comments, check-ins, and likes compared to both Generation X’ers and Baby Boomers.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study complements previous qualitative/descriptive work on SUD recovery support apps, such as a recent longitudinal study of a site for individuals who want to change their drinking, and a survey of individuals who use another recovery-specific social network site, with objective data that describes end-user characteristics and identifies predictors of relapse among the most engaged users of a recovery-support app. Findings suggest that a diverse set of individuals engage with Sober Grid at this more frequent rate, making use of several distinct features such as commenting, posting, liking, check-ins, and connecting/chatting with others.

Perhaps counterintuitively, given that young adults are more avid participants on social network sites than their middle and older adult counterparts, Baby Boomers and Generation X’ers made more use of the platform and its features than Millennials, evidenced by more connections and activity among these cohorts. While it’s impossible to determine the cause of this effect given the data available to the authors, they speculate that this may be a result of Sober Grid having greater appeal to older demographics given its emphasis on text-based status sharing and still image uploads. In contrast Millennials may prefer and be more likely to use social network apps featuring anonymous sharing and live/recorded video, such as Snapchat. It is also possible older users have experienced greater SUD related consequences and are thus more motivated to engage with platforms that can help them sustain recovery, and thus be more likely to use this app.

Among all participants, certain features were more utilized than others. Posts, comments, likes, check-ins, and chats were most utilized. These features are most like features available on popular social network sites like Facebook, and users may have felt more comfortable using them given their familiarity. The triggers and burning desires features were used less often. It is hard to say why this might have been the case, given these would features seem key to the app (i.e., asking for urgent help). It’s of course possible end-users did not experience many triggers or have burning desires to share or that individuals preferred to share this kind of information face-to-face or over the phone. It’s also possible users of this app lacked awareness of triggers, and therefore were less inclined to report them. If this is the case, it would support the case for just-in-time interventions that detect relapse risk outside of conscious awareness.

Emotional triggers most commonly reported by users were stress, depression/sadness, environmental, and loneliness, which is consistent with previous research describing risk factors for relapse and is an expected finding. Apps like Sober Grid have potential to help individuals manage emotional triggers. Though not a function of Sober Grid per se, other recovery support apps have the capacity to respond to emotional triggers with real-time coaching to help individuals cope in the moment.

Number of check-ins was a significant predictor of relapses determined by sobriety date changes, with more check-ins being uniquely associated with a greater number of relapses. suggests users who need more support, or are at higher risk of relapse, use the feature more often.

Though there is evidence in this paper that suggests many people find Sober Grid helpful, these kinds of apps typically have very low adoption rates. That is, although many people may download an app, most do not end up continuing to use the app in the long term. The fact the authors of this paper identified 102,242 unique users, and were only left with 1,273 after excluding those who did not report gender and age, and had less than 30 days between account creation and last login, and were infrequent app users, suggests this is also true for Sober Grid. That is to say, only a little over 1% of those who initially engaged with the app used it frequently.

Be that as it may, engaging individuals in any kind of alcohol or other drug treatment services is very challenging and there is room for improvement in engaging and retaining patients in traditional forms of addiction treatment too. Ultimately, the more treatment options available means greater likelihood that more individuals will find a recovery path that works for them, whether it’s traditional treatment, non-professional recovery support services such as mutual-help programs, or a digital recovery support service, such as this app.

Although more research is needed to establish Sober Grid’s efficacy, there is evidence to suggest such apps can have real public health impact, even if they’re not exclusively focused on substance use abstinence, in part, because they so many people can access them. For instance, the Daybreak site from Australia has been shown to help people reduce their alcohol use and risk, and was used by 50,000 individuals from 2016 to 2019.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- As noted by the authors, results cannot be generalized outside of the most active users of Sober Grid. That is, these findings don’t necessarily represent all Sober Grid users.

- Relatedly, because of non-trivial differences in SUD recovery support apps, these findings don’t necessarily characterize users of other SUD recovery support apps.

- The size of observed effects was generally fairly small, suggesting that other factors not currently tracked or available are more important in accurately modeling user behavior and recovery outcomes.

- And finally, though not necessarily a limitation per se, it is important to note that 3 of the paper’s authors work for Sober Grid.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: In this study of the smartphone application-based recovery-specific social network site, Sober Grid, that analyzed archived data of the most active app users, participants engaged with multiple platform features that may help support addiction recovery. On the whole, middle and older adults who were active app users tended to engage with the app more than young adults, though there is no evidence to suggest young adults derived any less benefit from it. Also, older adults were more likely to have longer sobriety length and report fewer relapses compared to young adults. Regardless of generation, having more unilateral connections was associated with longer sobriety length. Conversely, those with greater numbers of ‘check-ins’, on average, had shorter sobriety lengths, and greater number of relapses. Sober Grid, and other apps in this class like Daybreak, can help support SUD recovery are increasingly being used by individuals to augment or stand in place of first-line addiction treatments like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and mutual-help programs. Though apps like Sober Grid need to be better studied before they are recommended, theory and preliminary evidence suggests they can help at least some people. Given these apps are usually free or low cost, are easily accessible, and likely have few, if any negative side effects, they warrant exploration by individuals seeking addiction recovery.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: In this study of the smartphone application-based recovery-specific social network site, Sober Grid, that analyzed archived data of the most active app users, participants engaged with multiple platform features that may help support addiction recovery. On the whole, middle and older adults who were active app users tended to engage with the app more than young adults, though there is no evidence to suggest Millennials derived any less benefit from it. Also, older adults were more likely to have longer sobriety length and report fewer relapses compared to young adults. Regardless of generation, having more unilateral connections was associated with longer sobriety length. Conversely, those with greater numbers of ‘check-ins’, on average, had shorter sobriety lengths, and greater number of relapses. Sober Grid, and other apps in this class like Daybreak, can help support SUD recovery are increasingly being used by individuals to augment or stand in place of first-line addiction treatments like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and mutual-help programs. Though apps like Sober Grid need to be better studied, theory and preliminary evidence suggests they can help at least some people. Given these apps are usually free or low cost, are easily accessible, and likely have few, if any negative side effects, they warrant exploration by treatment providers and could be a useful addendum to first-line treatments.

- For scientists: In this study of the smartphone application-based recovery-specific social network site, Sober Grid, that analyzed archived data of the most active app users, participants engaged with multiple platform features that may help support addiction recovery. On the whole, middle and older adults who were active app users tended to engage with the app more than young adults, though there is no evidence to suggest Millennials derived any less benefit from it. Also, older adults were more likely to have longer sobriety length and report fewer relapses compared to young adults. Regardless of generation, having more unilateral connections was associated with longer sobriety length. Conversely, those with greater numbers of ‘check-ins’, on average, had shorter sobriety lengths, and greater number of relapses. Sober Grid, and other apps in this class like Daybreak, can help support SUD recovery are increasingly being used by individuals to augment or stand in place of first-line addiction treatments like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and mutual-help programs. Given the rapid growth of addiction recovery support apps, there’s a pressing need for research testing their efficacy, both as standalone services and as add-ons to treatment and mutual-help group attendance. Additionally, many of these apps provide objective data that can supplement self-report data for analysis of recovery outcomes.

- For policy makers: In this study of the smartphone application-based recovery-specific social network site, Sober Grid, that analyzed archived data of the most active app users, participants engaged with multiple platform features that may help support addiction recovery. On the whole, middle and older adults who were active app users tended to engage with the app more than young adults, though there is no evidence to suggest Millennials derived any less benefit from it. Also, older adults were more likely to have longer sobriety length and report fewer relapses compared to young adults. Regardless of generation, having more unilateral connections was associated with longer sobriety length. Conversely, those with greater numbers of ‘check-ins’, on average, had shorter sobriety lengths, and greater number of relapses. Digital recovery support services, accessible by website and smartphone app, represent a relatively low-cost way of reaching a very large number of individuals, and therefore have great potential to benefit overall public health even they if confer only a relatively small benefit at an individual level. For example, government initiatives like the Daybreak app in Australia, which is designed to help problem drinkers reduce or stop drinking was used by 50,000 individuals (0.2% of the entire population of Australia) from 2016 to 2019, and has been shown to significantly reduce alcohol use and alcohol related risk.

CITATIONS

Ashford, R. D., Giorgi, S., Mann, B., Pesce, C., Sherritt, L., Ungar, L., & Curtis, B. (2020). Digital recovery networks: Characterizing user participation, engagement, and outcomes of a novel recovery social network smartphone application. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 109, 50-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.11.005