Cutting the cost of cutting back on drinking

In the most under-resourced of health care settings, non-professional counselors with no prior mental health training have been found to increase alcohol abstinence and remission in primary health center settings in countries such as in India. This study is part of a larger effort to identify scalable, culturally appropriate, clinically effective and cost-effective interventions that can be broadly disseminated.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Brief psychological interventions based on motivational enhancement are the recommended first-line intervention for harmful drinking identified in routine health care settings (WHO 2010 Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol Report) However, in low resource settings, there are significant supply side barriers (low availability of mental health professionals) and demand side barriers (low levels of mental health literacy) leading to low implementation rates. If brief psychological treatment could be effectively provided by lay counselors in a primary care setting and if it can be demonstrated to be cost-effective in a resource-limited system such as that found in India, then this addresses multiple barriers to treatment.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Authors conducted a randomized controlled trial that compared the effectiveness of adding a Counseling for Alcohol Problems (CAP) program to enhanced usual care (EUC).

- Counseling for Alcohol Problems (CAP) Program

-

The CAP program involves an average of three (up to four) individualized sessions, 30-45min each, at weekly/biweekly intervals, based on motivational enhancement. Lay counselors (with a secondary education but no professional or mental health background) delivered this brief psychological treatment program during the course of routine care at ten publicly funded primary health centers in Goa, India in 2013-2015 serving a low socioeconomic population. The sessions were primarily administered in person at the health center, although sessions were also conducted in the patient’s home as well as over the telephone.

- Enhanced Usual Care (EUC) Program

-

In the enhanced usual care arm of the study (EUC), the primary health center physician was provided the results of the AUDIT and baseline questionnaires, as well at the WHO guidelines for harmful drinking, including when and where to refer patients for specialist care.

- READ MORE ON STUDY METHODS

-

Of the 14,773 male patients screened and 679 patient eligible, the study enrolled 377 adult males with AUDIT (the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test) scores of 12-19 (capturing moderate but not severe alcohol use). Those actively intoxicated, or needing medical treatment or inpatient admissions were excluded.

The primary outcomes were: remission (AUDIT scores <8) and mean daily alcohol consumed at three months.

Secondary outcomes included: disability score, days unable to work, suicide attempts, intimate partner violence, resource use and cost of illness.

This study is part of the PREMIUM (Program for Effective Mental Health Interventions in Under-Resourced Health Systems) research program (information about PREMIUM) and this study was administered concurrently with the Healthy Activity Program (an intervention for depression) at the same primary health centers, delivered by the same health counselors.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

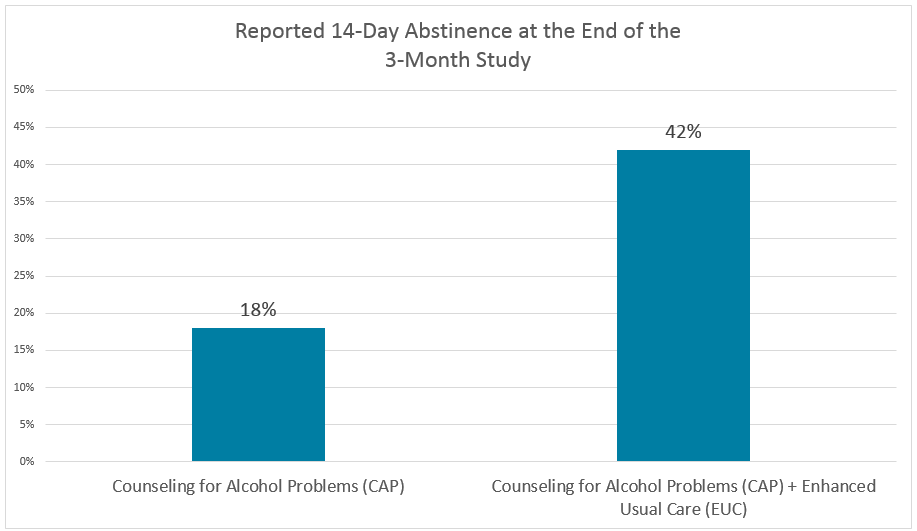

Participants receiving counseling (CAP) in addition to enhanced usual care (EUC) showed significantly higher remission and abstinence rates at three months: The proportion reporting abstinence at the end of the study was more than double in the group receiving additional counseling.

Remission rates were also improved in the counseling group: 36% of the CAP arm vs. 26% of EUC showed remission at three months (AUDIT scores <8). The percentage of days abstinent was also significantly lowered with counseling (adjusted mean difference of 16%; p<0.0001). The brief counseling interventions thus showed a large effect on abstinence and remission.

The beneficial effect of the CAP counseling seems to be mediated by increased abstinence rather than moderated drinking: Amongst those still drinking at three months, there was no statistical effect of counseling on mean daily alcohol consumed. In fact, the mean alcohol consumed by those still drinking in the counseling group was perhaps higher than in the control group (4 vs. 3 drinks per day but not statistically different), and the percentage of days of heavy drinking was no different between the two groups. Interestingly, there was a greater intervention effect on those not already trying to change drinking behavior at baseline for alcohol consumption (p=0.003), suggesting that CAP enhanced motivation to change, as expected.

Measures reflecting social and functional outcomes were not affected by the counseling intervention in this study: None of the secondary measures (which are often associated with more problematic drinking) in this study showed statistical differences between the CAP and the CAP+EUC groups. There were no statistical differences between the two groups on the WHO disability assessment scale, the Short Inventory of Problems Score, days unable to work, suicide attempts or intimate partner violence.

Cost analysis of this intervention: The incremental cost per additional remission was $217 with an 85% chance of being cost-effective in the study setting. This reflects primarily the cost of screening and training the lay counselors (who are rigorously selected to participate in a six-month internship) and includes supervision and salary costs. The cost of lost income for patients and their families was also included.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This is a remarkable study demonstrating that non-professionals can be effectively trained to provide quality, brief, motivating and personalized therapy that can enhance abstinence in harmful drinkers in a predominantly unskilled labor population and under-resourced setting. This study suggests that a brief counseling program can be implemented broadly in primary care and under-served areas in a cost-effective manner.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Only men were enrolled in this study as the prevalence of female drinking is as low as 1% in India – meaning that the findings here need to be shown to be applicable to settings where female harmful drinking is also present.

- One of the two primary outcomes (drinking over the past two weeks) is based on self-report, and all outcomes are questionnaire based, even measures of intimate partner violence.

- The study was slightly underpowered – they had fewer participants than the number needed to show an effect on mean alcohol consumed pre- and post-intervention, perhaps explaining why no statistical difference was shown for this measure (they had calculated needing 400 enrolled participants with harmful drinking to have 90% power to detect the hypothesized effect on mean alcohol consumed and this study included only 377 participants).

- Though the study was conducted for 12 months, the outcomes are only reported at three months (from the time of enrollment) – the authors state that they intend to assess the sustainability of the effect of the CAP intervention.

- The main effect was on abstinence. Per the authors, prevailing beliefs in India place great importance on abstinence. The magnitude of the effect may thus be culturally responsive in part, resulting in a larger CAP response in this particular population.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Engaging in motivational enhancement or other similar therapy for problematic or harmful drinking can significantly increase abstinence and remission, particularly for those not focused on changing their behavior or not defining their behavior as problematic. Having a brief intervention integrated as part of primary care delivery can help motivate change in drinkers who have not yet identified their drinking as problematic.

- For scientists: More studies are needed to determine which interventions can be effectively administered by trained laypeople without any formal mental health certification and which range of substance use severity can be treated in primary care settings without needing more specialized interventions. These kinds of studies can help broadly expand the accessibility of substance use treatment.

- For policy makers: The World Health Organization recommendations for brief counseling have now been validated in a low resource setting using trained laypeople and shown to be cost-effective. However, the challenge remains of how to shift some of the health care spending from expensive, intensive care of severe alcohol use disorders to more cost effective interventions earlier in patients’ drinking trajectories. Training of non-professionals to provide supervised and validated therapy in primary care settings is a cost effective intervention that does not have an obvious funding source. The challenge is to find a funding stream to help provide this level of care outside of a research environment, at least until the infrastructure is in place to allow insurance billing.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Primary care settings can provide effective substance use treatment interventions at low costs without needing mental health professionals for those with even moderate alcohol use disorders. However, it would benefit the field more broadly, if large health care systems encouraged screening and brief therapy in primary care settings, thus reducing the burden on the substance use treatment infrastructure and increasing access to care.

CITATIONS

Nadkarni, A., Weobong, B., Weiss, H. A., McCambridge, J., Bhat, B., Katti, B., … & Wilson, G. T. (2017). Counselling for Alcohol Problems (CAP), a lay counsellor-delivered brief psychological treatment for harmful drinking in men, in primary care in India: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 389(10065), 186-195.