Suboxone After Administering Vivitrol to Treat Cocaine Dependence?

Despite their best efforts, clinical addiction scientists have had a difficult time finding an effective medication for people with cocaine use disorder. There are currently no medications approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration to help reduce cocaine use.

Could the opioid treatment mainstay Suboxone (buprenorphine + naloxone) help those with cocaine use disorder?

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

One complicating factor in people receiving treatment for opioid use disorder is whether or not they also use cocaine. Studies of medication assisted treatments, such as methadone and buprenorphine (Suboxone) have found co-occurring cocaine use is present in 40 to 45% of patients. Most importantly, those who also use cocaine are more likely to drop out of treatment and have worse outcomes compared to those who do not use cocaine.

Addiction researchers have been evaluating medications to address cocaine use disorders for decades, providing few promising choices to date. Interestingly, laboratory experiments with rodents and some preliminary studies with humans have found buprenorphine may also help reduce cocaine use by alleviating stress-related craving – independent from its ability to reduce opioid craving. In terms of how it might do this, its effect on opioids is thought to occur by partially stimulating mu opioid receptors. However its effect on cocaine use is thought to occur by blocking kappa opioid receptors.

This study collaborated with 11 different treatment sites across the U.S. and tested whether adding two different doses of buprenorphine (Suboxone) after administering extended-release injection naltrexone could help reduce cocaine use in those with current cocaine use disorder and either current or past opioid use disorder. All individuals were administered the naltrexone injection first to reduce the likelihood of developing a physical dependency on the buprenorphine.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

In a randomized controlled trial study design, in addition to a once-per-month 380mg injection of extended release naltrexone (Vivitrol):

- 97 patients received 16mg of buprenorphine (Suboxone)

- 95 patients received 4 mg of buprenorphine (Suboxone)

- 100 patients received a placebo medication.

- READ MORE ON STUDY METHODS

-

To reduce the impact of expectancies on outcome, all three groups took two identical-sized pills. Neither patients nor those administering the medication knew which they were getting (i.e., it was a “double blind”, placebo-controlled study).

Toxicology screens were administered three times per week and the primary outcome was self-reported cocaine use adjusted for these toxicology screen results. For example, a predetermined number of self-reported negative days were modified if a toxicology screen was positive using a sophisticated procedure. This strategy combining self-report with toxicology screen results offers a more complete picture of patients’ use because urine toxicology screens only pick up cocaine use up to about 3 days – it’s possible small amounts of use may not be picked up at all. So a negative screen is not a certain indicator of abstinence, and a positive screen is only indicative of whether or not they used cocaine, not how much or how often.

All patients met current criteria for cocaine use disorder, as well as either current or past opioid use disorder based on the fourth edition of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV). Treatment lasted for 8 weeks, during which time all patients also received weekly individual cognitive behavioral therapy. Patients needed to begin the trial abstinent from opioids and they received take-home doses between their visits to the clinic three times per week. They were followed up at 1 and 3-months after the 8-week intervention. Blood tests helped evaluate whether patients were actually taking the medication.

On average, the sample was approximately 46 years old while across groups 79% were male, 58-68% Black and 8-12% Hispanic. Across the three groups, participants used cocaine for between 9-11 of the 30 days, on average,before the study began, and had long histories of use (an average of 18-19 years). In addition to opioid use disorder (the substantial majority of which had current diagnoses), 70-82% had lifetime alcohol use disorder and 40-49% cannabis use disorder.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Overall, there were few differences between groups

Each of the groups – 16mg buprenorphine (Suboxone), 4mg buprenorphine (Suboxone), and placebo – all had small reductions (1 to 2 more days abstinent) in self-reported cocaine use from the 4 weeks before the trial to the final 4 weeks of treatment, corrected for toxicology screen results. But reductions were similar to each other.

There were also no group differences at the 1-month or 3-month follow-ups on cocaine use.

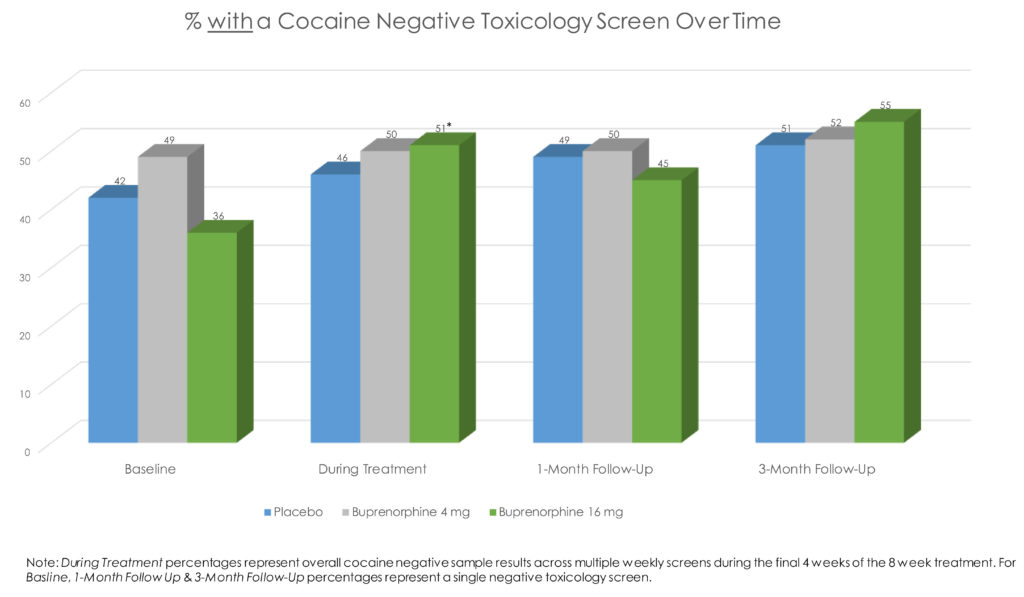

When looking only at the toxicology screen results, those in 16mg buprenorphine had 70% greater odds of a negative screen at any given point. However, again, the actual difference was small (45% of screens across the sample were cocaine negative in placebo vs. 50% and 51% in the buprenorphine 4mg and 16mg groups, respectively). There were no group differences on adhering to the medication regimen.

It is worth nothing only about 70% of patients in the buprenorphine conditions were fully adherent. There were also no differences on treatment drop out or adverse events.

Surprisingly, though actual opioid use was low (less than 1 day out of 30 on average in all groups), patients in the 16mg buprenorphine group reported more opioid use and opioid craving at 1-month follow-up compared to the placebo group. Also both buprenorphine (Suboxone) groups reported more craving than placebo at 3-months.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT?

The benefits appear to be small for the treatment of cocaine use disorder using Suboxone in tandem with Vivitrol.

One concern is that Suboxone patients experienced more opioid cravings than those taking placebo. It is unclear why this occurred, though it is possible that the stimulation of opioid receptors occurring with 16mg Suboxone overpowered the blocking effects of extended release naltrexone, and could have kindled this craving. Certainly, if Suboxone is to be evaluated further as a treatment for cocaine use in those with histories of opioid use disorder, the possible unintended harmful effect on opioid-related craving needs to be clarified.

While medication assisted treatments for cocaine use disorder are lacking, this well designed randomized trial suggests any benefits of Suboxone do not outweigh the risks at present.

Based on the current evidence, the treatments of choice for individuals with cocaine use disorder are mainly psychological and behavioral.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- As authors pointed out, this trial focused on cocaine use disorder, but all patients had a history of opioid use disorder as well. This study cannot be generalized to all individuals with cocaine use disorder.

- Also, because all individuals received cognitive behavioral therapy, the effects of the medications cannot be generalized to individuals who are not also receiving individual, psychosocial treatment.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Although there are some promising medications for cocaine use disorder, such as was highlighted in this study, none are considered to have solid enough evidence to be provided in real-world settings. If you or your loved one are having difficulties with cocaine use, talk therapies (e.g., 12-step facilitation, which helps an individual actively engage with community-based 12-step groups), and treatments that provide rewards for cocaine abstinence (often called contingency management) are considered by many to be the treatments of choice.

- For Scientists: This well done, randomized controlled trial of medication assisted treatment for cocaine use disorder showed only a modest benefit on one of many outcomes tested for buprenorphine (Suboxone) on cocaine use. Future studies may test whether better buprenorphine adherence leads to a more magnified benefit. Overall, the clinical scientific evidence for medication assisted treatment to address cocaine use disorder lags well behind that for opioid and alcohol use disorders.

- For Policy makers: Despite some promising medications, at present, there are no reliable, evidence-based medication assisted treatment options for individuals with cocaine use disorder.

- For Treatment professionals and treatment systems: Based on the current evidence, the treatments of choice for individuals with cocaine use disorder are mainly psychological and behavioral. These treatments include 12-step facilitation (referred to in the clinical research literature for cocaine use disorder as individual drug counseling), and contingency management, which offers a substantial body of evidence supporting its ability to help reduce cocaine use in the short-term.

CITATIONS

Ling, W., Hillhouse, M. P., Saxon, A. J., Mooney, L. J., Thomas, C. M., Ang, A., … & Liu, D. S. (2016). Buprenorphine+ naloxone plus naltrexone for the treatment of cocaine dependence: the Cocaine Use Reduction with Buprenorphine (CURB) study. Addiction.