l

Medication knowledge refers to the information that a patient has about the medicines they are prescribed, including dosage, route of administration, and potential side effects. Low medication knowledge may reflect more ambivalence about the reasons for taking the medication. In turn, this may lead to low treatment adherence and, ultimately, to worse health outcomes for patients with chronic conditions. In addition, insufficient medication knowledge can lead to increased use of medical services such as emergency department visits, resulting in increased patient costs. Research shows that patients’ medication knowledge tends to decrease as the number of medications prescribed increases.

Substance use disorder patients often have a wide range of co-occurring conditions requiring adherence to multiple medication regimens. For instance, people struggling with addiction often suffer from chronic physical (e.g., cardiovascular, liver, and pancreatic) and psychiatric (e.g., anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress) disorders. Accurately adhering to medication regimens for each of these conditions (in addition to potential substance use disorder treatments) is critical for ensuring the health of patients with substance use disorders. Given that medication knowledge is associated with adherence, it is vital to understand medication knowledge among patients with substance use disorders. However, there is little information in this regard. To address this knowledge gap, this study examined medication knowledge among patients with substance use disorders receiving in-patient care.

This study utilized structured one-on-one interviews with 100 psychiatric patients receiving in-patient alcohol detoxification treatment at the Department of Psychiatry, Social Psychiatry, and Psychotherapy of Hannover Medical School in Hannover, Germany. Detoxification procedures included administration of oxazepam to prevent alcohol withdrawal (e.g., seizures, delirium, and blood pressure dysregulation), and thiamine and a vitamin B complex to prevent Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome which can occur in chronic/severe alcohol use disorder cases.

Patients undergoing treatment were informed of the study aims and provided informed consent before being screened for eligibility. Patients were deemed eligible to participate if they 1) had a substance use disorder (e.g. alcohol use disorder), 2) had been regularly taking at least 1 medication (in addition to medication prescribed as part of detoxification treatment), 3) had been undergoing in-patient treatment for 72 or more hours, and 4) did not show cognitive impairment in the clinical examination. All participants were recruited between March 2023 and April 2024.

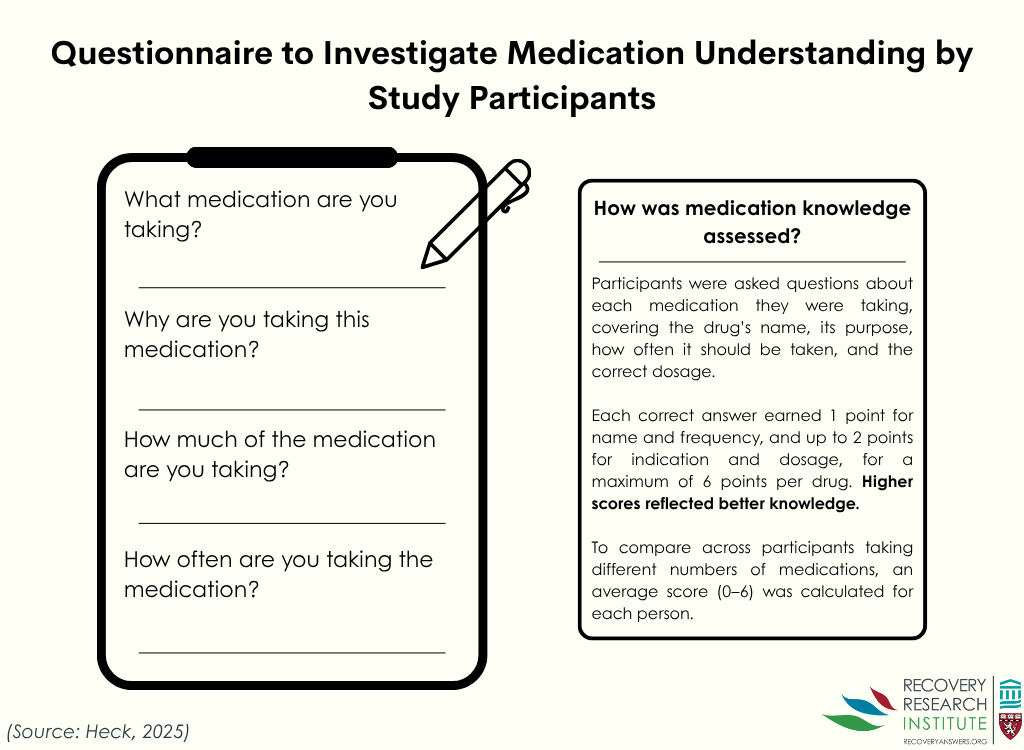

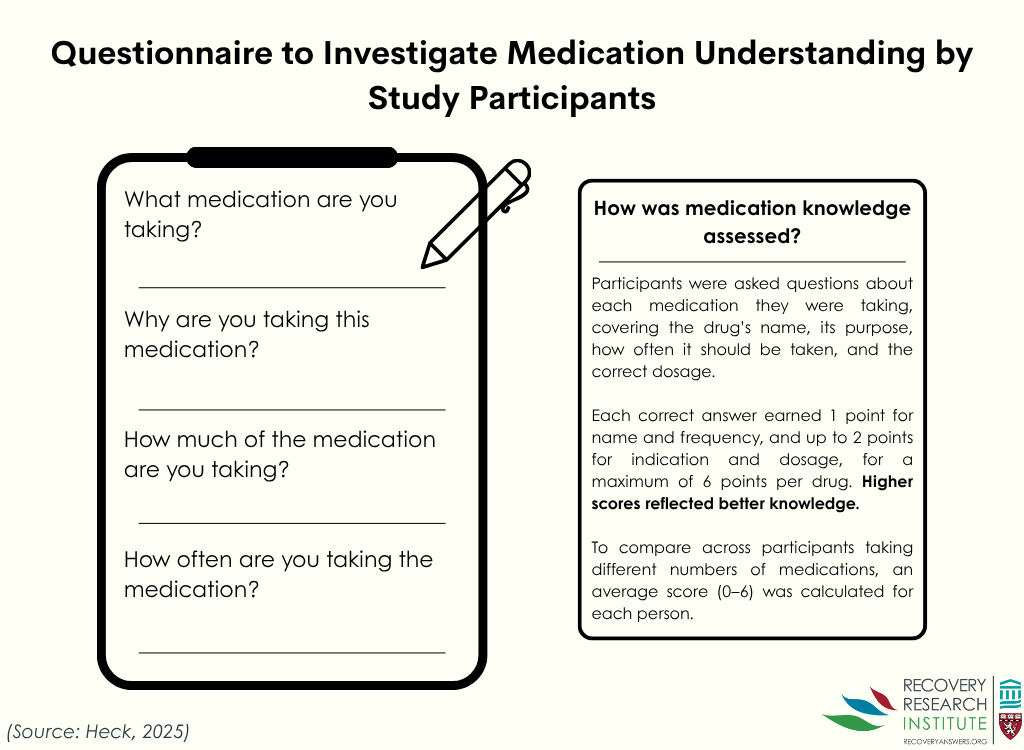

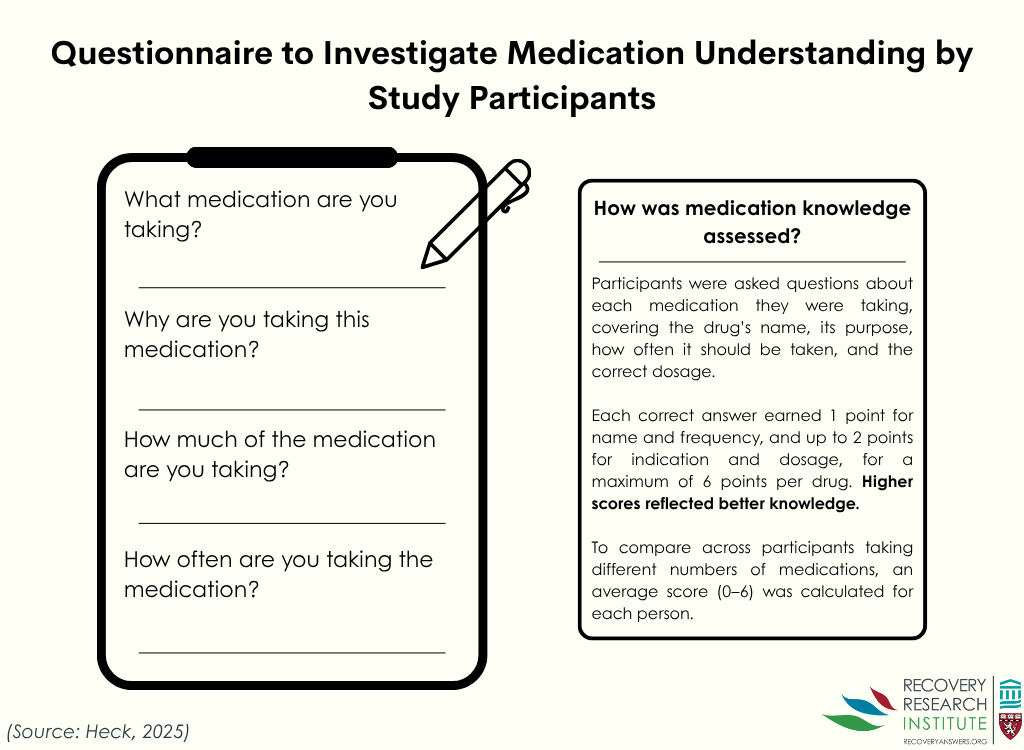

The main outcome of the present study was medication knowledge derived via an adapted questionnaire (graphic below). This questionnaire was designed to assess patients’ knowledge of each of the medications they were prescribed, including medication name, indication (i.e., the illness/condition the medication treated), dosage, and administration frequency. Question responses were used to calculate medication knowledge scores for each medicine prescribed with points being awarded for accurate responses. For example, 1 point was awarded for accurately recalling medication names and up to 2 points were given for correctly listing medication indications. Patients’ overall medication knowledge scores were derived by averaging all individual medication scores, resulting in a total score ranging from 0 (no accurate responses) to 6 (all accurate responses), with higher scores indicating better medication knowledge.

Patients also indicated from where they obtained medication knowledge (e.g., from a medical doctor, their partner/spouse, or the Internet). Medications were classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification– a classification system whereby medications are divided into groups based on the organs/systems which they affect and their chemical, pharmacological, and therapeutic properties.

This study consisted of 100 patients. The sample was slightly more male (62%). The median participant age was 46.5 years. The median number of daily medications taken by participants was 6. The most common substance use disorder among patients was alcohol use disorder (89%), followed by cannabis use disorder (21%) and cocaine use disorder (14%). Comorbid psychiatric conditions among patients were common: over half were diagnosed with depression (53%), while 23% and 20% had diagnoses of personality disorder and/or post-traumatic stress disorder, respectively. Concurrent health conditions among patients included hypertension (26%), type 2 diabetes (8%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (7%).

Patients had lower medication knowledge for substance use withdrawal medications

The average overall medication knowledge score was 3.8. However, patients had more accurate knowledge of their regular medicines than their withdrawal medications (see graph below). The median score for regular medication knowledge was 4.8 compared to 3.0 for withdrawal medications.

Patients’ medication knowledge was lower for medicines that affected metabolism compared to other categories

Patients’ median medication knowledge score for digestive tract and metabolism medications was 3. In contrast, patients’ medication knowledge scores for cardiovascular and nervous system medications were both 5.

Most patients received information about their medications from medical doctors

Most patients (78%) received information about their medications from hospital physicians, general practitioners, or specialists. The remaining patients reporting getting health information from the internet (15%), their “own professional expertise” (3%), a spouse/partner (2%), or pharmacies/medication package inserts (2%).

The results of this study show that medication knowledge varied by medication type among hospitalized substance use disorder patients. Patients had less accurate information about substance use withdrawal medications compared to other medications they were prescribed. This may be because medical detoxification is a stressful time, during which patients’ cognitive abilities are lower than usual. Or, given the typically brief nature of the duration of use such medications, patients are less inclined to bother learning more about them. Alternatively, given that withdrawal medications were newer, patients may have had lower ability to acquire new knowledge relative to medications they had been taking for a longer period of time. Whether this lower knowledge also applied to alcohol use disorder medications, like naltrexone and acamprosate, could not be determined as medication knowledge was only assessed during medical detoxification. If, in fact, medication knowledge was lower for addiction medications someone was taking ongoing, this would be more problematic. This is an important question for future research. Also not examined here was whether participant access to electronic health record portals – where patients can see their current medication regiment, upcoming appointments, etc. – potentially improved medication knowledge.

Overall, while in an important area, the utility of the medication knowledge components and score need further study. For instance, a patient who answered that they took “Zoloft, against listlessness, one tablet in the morning” would achieve 4 out of 6 possible points for this drug (a perfect, 6- point answer in this example would have been: “Zoloft, against depression, one 50-mg tablet in the morning”). However, it is unclear if knowing these details are predictive of clinical outcomes. In practice, adherence may depend more on knowing the correct pill count and dosing schedule than on recalling the exact milligram dose or the formal diagnosis associated with the prescription. Therefore, whether there is a useful difference between scores above a certain threshold is not clear.

Also, the lack of a comparison group and the absence of controls for the total number of prescribed medications limit interpretation. For instance, patients with diabetes often manage multiple comorbidities (e.g., neuropathy, retinopathy, etc.), requiring complex treatment regimens. Without accounting for such parallels, it is unclear whether lower medication knowledge observed in patients with substance use disorders is unique to this population or analogous to challenges faced by other patients with complex arrays of comorbid conditions.

Further research is needed to examine how knowledge of substance use disorder treatment medications may be associated with treatment adherence and health outcomes.

This cross-sectional study shows that patients undergoing inpatient alcohol detoxification had varying levels of knowledge of their prescribed medications. Patients displayed moderately high levels of medication knowledge overall, but their knowledge of their withdrawal medications was significantly lower compared to their other prescribed medications, possibly because of the short-term, new, and limited, exposure to them. Though not assessed directly in this study, medication knowledge is known to be associated with treatment adherence, which is critical for treatment success. However, this study could not determine how knowledge of outpatient medications for alcohol use disorder, like naltrexone and acamprosate, may be associated with treatment adherence, nor did it compare medication knowledge of these inpatients underdoing medical detoxification to individuals with other chronic diseases like diabetes. Further research is needed to examine how knowledge of substance use disorder treatment medications may be associated with treatment adherence and health outcomes.

Heck, J., Dubaschewski, M., Krause, O., Bleich, S., Schulze Westhoff, M., Krichevsky, B., Glahn, A., & Schröder, S. (2025). What do patients with substance use disorders know about their medication? A cross-sectional interview-based study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 16. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1556920.

l

Medication knowledge refers to the information that a patient has about the medicines they are prescribed, including dosage, route of administration, and potential side effects. Low medication knowledge may reflect more ambivalence about the reasons for taking the medication. In turn, this may lead to low treatment adherence and, ultimately, to worse health outcomes for patients with chronic conditions. In addition, insufficient medication knowledge can lead to increased use of medical services such as emergency department visits, resulting in increased patient costs. Research shows that patients’ medication knowledge tends to decrease as the number of medications prescribed increases.

Substance use disorder patients often have a wide range of co-occurring conditions requiring adherence to multiple medication regimens. For instance, people struggling with addiction often suffer from chronic physical (e.g., cardiovascular, liver, and pancreatic) and psychiatric (e.g., anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress) disorders. Accurately adhering to medication regimens for each of these conditions (in addition to potential substance use disorder treatments) is critical for ensuring the health of patients with substance use disorders. Given that medication knowledge is associated with adherence, it is vital to understand medication knowledge among patients with substance use disorders. However, there is little information in this regard. To address this knowledge gap, this study examined medication knowledge among patients with substance use disorders receiving in-patient care.

This study utilized structured one-on-one interviews with 100 psychiatric patients receiving in-patient alcohol detoxification treatment at the Department of Psychiatry, Social Psychiatry, and Psychotherapy of Hannover Medical School in Hannover, Germany. Detoxification procedures included administration of oxazepam to prevent alcohol withdrawal (e.g., seizures, delirium, and blood pressure dysregulation), and thiamine and a vitamin B complex to prevent Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome which can occur in chronic/severe alcohol use disorder cases.

Patients undergoing treatment were informed of the study aims and provided informed consent before being screened for eligibility. Patients were deemed eligible to participate if they 1) had a substance use disorder (e.g. alcohol use disorder), 2) had been regularly taking at least 1 medication (in addition to medication prescribed as part of detoxification treatment), 3) had been undergoing in-patient treatment for 72 or more hours, and 4) did not show cognitive impairment in the clinical examination. All participants were recruited between March 2023 and April 2024.

The main outcome of the present study was medication knowledge derived via an adapted questionnaire (graphic below). This questionnaire was designed to assess patients’ knowledge of each of the medications they were prescribed, including medication name, indication (i.e., the illness/condition the medication treated), dosage, and administration frequency. Question responses were used to calculate medication knowledge scores for each medicine prescribed with points being awarded for accurate responses. For example, 1 point was awarded for accurately recalling medication names and up to 2 points were given for correctly listing medication indications. Patients’ overall medication knowledge scores were derived by averaging all individual medication scores, resulting in a total score ranging from 0 (no accurate responses) to 6 (all accurate responses), with higher scores indicating better medication knowledge.

Patients also indicated from where they obtained medication knowledge (e.g., from a medical doctor, their partner/spouse, or the Internet). Medications were classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification– a classification system whereby medications are divided into groups based on the organs/systems which they affect and their chemical, pharmacological, and therapeutic properties.

This study consisted of 100 patients. The sample was slightly more male (62%). The median participant age was 46.5 years. The median number of daily medications taken by participants was 6. The most common substance use disorder among patients was alcohol use disorder (89%), followed by cannabis use disorder (21%) and cocaine use disorder (14%). Comorbid psychiatric conditions among patients were common: over half were diagnosed with depression (53%), while 23% and 20% had diagnoses of personality disorder and/or post-traumatic stress disorder, respectively. Concurrent health conditions among patients included hypertension (26%), type 2 diabetes (8%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (7%).

Patients had lower medication knowledge for substance use withdrawal medications

The average overall medication knowledge score was 3.8. However, patients had more accurate knowledge of their regular medicines than their withdrawal medications (see graph below). The median score for regular medication knowledge was 4.8 compared to 3.0 for withdrawal medications.

Patients’ medication knowledge was lower for medicines that affected metabolism compared to other categories

Patients’ median medication knowledge score for digestive tract and metabolism medications was 3. In contrast, patients’ medication knowledge scores for cardiovascular and nervous system medications were both 5.

Most patients received information about their medications from medical doctors

Most patients (78%) received information about their medications from hospital physicians, general practitioners, or specialists. The remaining patients reporting getting health information from the internet (15%), their “own professional expertise” (3%), a spouse/partner (2%), or pharmacies/medication package inserts (2%).

The results of this study show that medication knowledge varied by medication type among hospitalized substance use disorder patients. Patients had less accurate information about substance use withdrawal medications compared to other medications they were prescribed. This may be because medical detoxification is a stressful time, during which patients’ cognitive abilities are lower than usual. Or, given the typically brief nature of the duration of use such medications, patients are less inclined to bother learning more about them. Alternatively, given that withdrawal medications were newer, patients may have had lower ability to acquire new knowledge relative to medications they had been taking for a longer period of time. Whether this lower knowledge also applied to alcohol use disorder medications, like naltrexone and acamprosate, could not be determined as medication knowledge was only assessed during medical detoxification. If, in fact, medication knowledge was lower for addiction medications someone was taking ongoing, this would be more problematic. This is an important question for future research. Also not examined here was whether participant access to electronic health record portals – where patients can see their current medication regiment, upcoming appointments, etc. – potentially improved medication knowledge.

Overall, while in an important area, the utility of the medication knowledge components and score need further study. For instance, a patient who answered that they took “Zoloft, against listlessness, one tablet in the morning” would achieve 4 out of 6 possible points for this drug (a perfect, 6- point answer in this example would have been: “Zoloft, against depression, one 50-mg tablet in the morning”). However, it is unclear if knowing these details are predictive of clinical outcomes. In practice, adherence may depend more on knowing the correct pill count and dosing schedule than on recalling the exact milligram dose or the formal diagnosis associated with the prescription. Therefore, whether there is a useful difference between scores above a certain threshold is not clear.

Also, the lack of a comparison group and the absence of controls for the total number of prescribed medications limit interpretation. For instance, patients with diabetes often manage multiple comorbidities (e.g., neuropathy, retinopathy, etc.), requiring complex treatment regimens. Without accounting for such parallels, it is unclear whether lower medication knowledge observed in patients with substance use disorders is unique to this population or analogous to challenges faced by other patients with complex arrays of comorbid conditions.

Further research is needed to examine how knowledge of substance use disorder treatment medications may be associated with treatment adherence and health outcomes.

This cross-sectional study shows that patients undergoing inpatient alcohol detoxification had varying levels of knowledge of their prescribed medications. Patients displayed moderately high levels of medication knowledge overall, but their knowledge of their withdrawal medications was significantly lower compared to their other prescribed medications, possibly because of the short-term, new, and limited, exposure to them. Though not assessed directly in this study, medication knowledge is known to be associated with treatment adherence, which is critical for treatment success. However, this study could not determine how knowledge of outpatient medications for alcohol use disorder, like naltrexone and acamprosate, may be associated with treatment adherence, nor did it compare medication knowledge of these inpatients underdoing medical detoxification to individuals with other chronic diseases like diabetes. Further research is needed to examine how knowledge of substance use disorder treatment medications may be associated with treatment adherence and health outcomes.

Heck, J., Dubaschewski, M., Krause, O., Bleich, S., Schulze Westhoff, M., Krichevsky, B., Glahn, A., & Schröder, S. (2025). What do patients with substance use disorders know about their medication? A cross-sectional interview-based study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 16. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1556920.

l

Medication knowledge refers to the information that a patient has about the medicines they are prescribed, including dosage, route of administration, and potential side effects. Low medication knowledge may reflect more ambivalence about the reasons for taking the medication. In turn, this may lead to low treatment adherence and, ultimately, to worse health outcomes for patients with chronic conditions. In addition, insufficient medication knowledge can lead to increased use of medical services such as emergency department visits, resulting in increased patient costs. Research shows that patients’ medication knowledge tends to decrease as the number of medications prescribed increases.

Substance use disorder patients often have a wide range of co-occurring conditions requiring adherence to multiple medication regimens. For instance, people struggling with addiction often suffer from chronic physical (e.g., cardiovascular, liver, and pancreatic) and psychiatric (e.g., anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress) disorders. Accurately adhering to medication regimens for each of these conditions (in addition to potential substance use disorder treatments) is critical for ensuring the health of patients with substance use disorders. Given that medication knowledge is associated with adherence, it is vital to understand medication knowledge among patients with substance use disorders. However, there is little information in this regard. To address this knowledge gap, this study examined medication knowledge among patients with substance use disorders receiving in-patient care.

This study utilized structured one-on-one interviews with 100 psychiatric patients receiving in-patient alcohol detoxification treatment at the Department of Psychiatry, Social Psychiatry, and Psychotherapy of Hannover Medical School in Hannover, Germany. Detoxification procedures included administration of oxazepam to prevent alcohol withdrawal (e.g., seizures, delirium, and blood pressure dysregulation), and thiamine and a vitamin B complex to prevent Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome which can occur in chronic/severe alcohol use disorder cases.

Patients undergoing treatment were informed of the study aims and provided informed consent before being screened for eligibility. Patients were deemed eligible to participate if they 1) had a substance use disorder (e.g. alcohol use disorder), 2) had been regularly taking at least 1 medication (in addition to medication prescribed as part of detoxification treatment), 3) had been undergoing in-patient treatment for 72 or more hours, and 4) did not show cognitive impairment in the clinical examination. All participants were recruited between March 2023 and April 2024.

The main outcome of the present study was medication knowledge derived via an adapted questionnaire (graphic below). This questionnaire was designed to assess patients’ knowledge of each of the medications they were prescribed, including medication name, indication (i.e., the illness/condition the medication treated), dosage, and administration frequency. Question responses were used to calculate medication knowledge scores for each medicine prescribed with points being awarded for accurate responses. For example, 1 point was awarded for accurately recalling medication names and up to 2 points were given for correctly listing medication indications. Patients’ overall medication knowledge scores were derived by averaging all individual medication scores, resulting in a total score ranging from 0 (no accurate responses) to 6 (all accurate responses), with higher scores indicating better medication knowledge.

Patients also indicated from where they obtained medication knowledge (e.g., from a medical doctor, their partner/spouse, or the Internet). Medications were classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification– a classification system whereby medications are divided into groups based on the organs/systems which they affect and their chemical, pharmacological, and therapeutic properties.

This study consisted of 100 patients. The sample was slightly more male (62%). The median participant age was 46.5 years. The median number of daily medications taken by participants was 6. The most common substance use disorder among patients was alcohol use disorder (89%), followed by cannabis use disorder (21%) and cocaine use disorder (14%). Comorbid psychiatric conditions among patients were common: over half were diagnosed with depression (53%), while 23% and 20% had diagnoses of personality disorder and/or post-traumatic stress disorder, respectively. Concurrent health conditions among patients included hypertension (26%), type 2 diabetes (8%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (7%).

Patients had lower medication knowledge for substance use withdrawal medications

The average overall medication knowledge score was 3.8. However, patients had more accurate knowledge of their regular medicines than their withdrawal medications (see graph below). The median score for regular medication knowledge was 4.8 compared to 3.0 for withdrawal medications.

Patients’ medication knowledge was lower for medicines that affected metabolism compared to other categories

Patients’ median medication knowledge score for digestive tract and metabolism medications was 3. In contrast, patients’ medication knowledge scores for cardiovascular and nervous system medications were both 5.

Most patients received information about their medications from medical doctors

Most patients (78%) received information about their medications from hospital physicians, general practitioners, or specialists. The remaining patients reporting getting health information from the internet (15%), their “own professional expertise” (3%), a spouse/partner (2%), or pharmacies/medication package inserts (2%).

The results of this study show that medication knowledge varied by medication type among hospitalized substance use disorder patients. Patients had less accurate information about substance use withdrawal medications compared to other medications they were prescribed. This may be because medical detoxification is a stressful time, during which patients’ cognitive abilities are lower than usual. Or, given the typically brief nature of the duration of use such medications, patients are less inclined to bother learning more about them. Alternatively, given that withdrawal medications were newer, patients may have had lower ability to acquire new knowledge relative to medications they had been taking for a longer period of time. Whether this lower knowledge also applied to alcohol use disorder medications, like naltrexone and acamprosate, could not be determined as medication knowledge was only assessed during medical detoxification. If, in fact, medication knowledge was lower for addiction medications someone was taking ongoing, this would be more problematic. This is an important question for future research. Also not examined here was whether participant access to electronic health record portals – where patients can see their current medication regiment, upcoming appointments, etc. – potentially improved medication knowledge.

Overall, while in an important area, the utility of the medication knowledge components and score need further study. For instance, a patient who answered that they took “Zoloft, against listlessness, one tablet in the morning” would achieve 4 out of 6 possible points for this drug (a perfect, 6- point answer in this example would have been: “Zoloft, against depression, one 50-mg tablet in the morning”). However, it is unclear if knowing these details are predictive of clinical outcomes. In practice, adherence may depend more on knowing the correct pill count and dosing schedule than on recalling the exact milligram dose or the formal diagnosis associated with the prescription. Therefore, whether there is a useful difference between scores above a certain threshold is not clear.

Also, the lack of a comparison group and the absence of controls for the total number of prescribed medications limit interpretation. For instance, patients with diabetes often manage multiple comorbidities (e.g., neuropathy, retinopathy, etc.), requiring complex treatment regimens. Without accounting for such parallels, it is unclear whether lower medication knowledge observed in patients with substance use disorders is unique to this population or analogous to challenges faced by other patients with complex arrays of comorbid conditions.

Further research is needed to examine how knowledge of substance use disorder treatment medications may be associated with treatment adherence and health outcomes.

This cross-sectional study shows that patients undergoing inpatient alcohol detoxification had varying levels of knowledge of their prescribed medications. Patients displayed moderately high levels of medication knowledge overall, but their knowledge of their withdrawal medications was significantly lower compared to their other prescribed medications, possibly because of the short-term, new, and limited, exposure to them. Though not assessed directly in this study, medication knowledge is known to be associated with treatment adherence, which is critical for treatment success. However, this study could not determine how knowledge of outpatient medications for alcohol use disorder, like naltrexone and acamprosate, may be associated with treatment adherence, nor did it compare medication knowledge of these inpatients underdoing medical detoxification to individuals with other chronic diseases like diabetes. Further research is needed to examine how knowledge of substance use disorder treatment medications may be associated with treatment adherence and health outcomes.

Heck, J., Dubaschewski, M., Krause, O., Bleich, S., Schulze Westhoff, M., Krichevsky, B., Glahn, A., & Schröder, S. (2025). What do patients with substance use disorders know about their medication? A cross-sectional interview-based study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 16. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1556920.

151 Merrimac St., 4th Floor. Boston, MA 02114