Using the Child Welfare System to Engage Parents with Substance Use Disorders

Although some substance use disorders (SUDs) can remit without formal treatment, receiving treatment substantially increases one’s chances of abstinence and recovery. However, only about 10% of individuals with substance use disorder (SUD) receive treatment each year.

In order to help more individuals get into recovery, and do so more quickly, the system must find ways to take advantage of opportunities to assess for substance use disorder (SUD), and offer and facilitate treatment entry when indicated.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

In this study, Traube et al. described the Child Protection Substance Abuse Initiative (CPSAI), a program in New Jersey targeting parents engaged in the Division of Child Protection and Permanence, part of their child welfare system. In other words, these parents were referred to state services because it was determined (e.g., by a professional) that their child’s well-being was at risk for reasons including abuse or neglect. Authors also examined factors related to completing substance use disorder (SUD) treatment when it was initiated by this program.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study outlined a novel program that aimed:

- to assess and facilitate treatment engagement for parents being evaluated by the child welfare system

- to document proportions that received specialized assessment, were referred to treatment, and completed treatment

- to examine individual factors that predicted successful treatment completion for those who were referred to treatment

Regarding the program logistics, the Division of Child Protection first identifies clients with possible substance use disorder (SUD), and refers these clients to certified drug/alcohol counselors located in their office. The counselor makes extensive efforts to engage the client, including at least three communication attempts within 30 days (e.g., phone, mail, or hand-delivered letters). The counselors then conduct a clinical and service needs assessment, identify state-contracted SUD treatment programs, refer clients to these programs as needed, and help facilitate the client’s entry into treatment at the appropriate level of care (e.g., inpatient or outpatient).

After referring the client, the counselor continues to help with case management for up to 30 days, or until the client enters substance use disorder (SUD) treatment. Refer below to “What did this study find” for the proportions of clients that were referred to, and engaged with treatment. Of note, the program provided increased funding to the referral source SUD programs to address the influx of clients from the child welfare system and special needs of these parents (e.g., programs offered groups on parenting).

Nearly 14,000 clients (18 years or older) were admitted to the program from October 2009 to September 2010. If there was more than one referral, only the most recent referral was selected for tracking.

Primary outcomes included:

- referral for, and receipt of SUD assessment

- receipt of any SUD treatment

- SUD treatment completion

Authors also investigated whether any of the following factors predicted treatment completion for those who were referred: age, gender, race/ethnicity, employment, and legal status.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

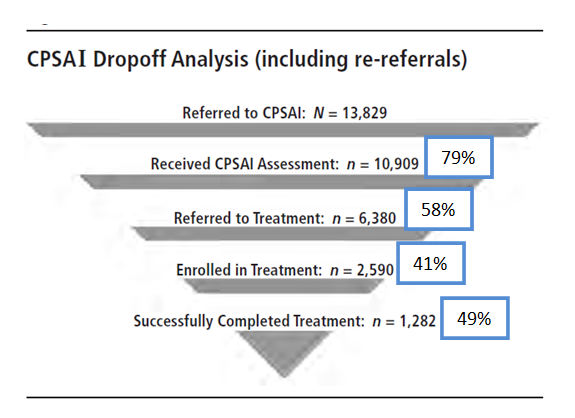

Of the 13,829 referred to the program, 1,282 completed substance use disorder (SUD) treatment (9%).

It is important to note that some clients were still in treatment when the cut-off for the analyses was established. So the number of treatment completers may be higher than reported in the figure.

The researchers did not perform analyses to examine if differences in these steps differed significantly based on their demographic characteristics. Descriptively, however, there were some potentially meaningful differences.

Regarding ethnicity, of those who were assessed, Hispanics had the lowest referral to treatment (White, 63%; African American, 60%; Hispanic, 50%). Among those who entered treatment, however, Hispanics had the highest completion rates and African Americans the lowest (Hispanic, 59%; White, 56%; African American, 48%).While minority clients were significantly more likely to complete treatment if referred, African American clients may have been less likely to complete treatment among those who actually entered treatment. This is somewhat consistent with data from large, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) studies of substance use disorder (SUD) treatment. These data show that, among those who are in need of SUD treatment, African Americans are more likely than other ethnic/racial groups to seek help (15% vs. 10%; see here). However, once they enter treatment, African American and Hispanic patients may be less likely to complete substance use disorder (SUD) treatment than Whites (see here). In other words, Whites might be less likely to follow up with a referral to treatment, but once engaged, minorities – particularly African Americans – appear to be more difficult to retain in care.

The exact reasons for this are not entirely clear, and warrant more in depth investigation. One possibility is that minorities may have more psychosocial challenges than Whites (e.g., lower income, transportation barriers, housing instability). These resources that can make it easier to initiate and sustain recovery, and which ongoing abstinence/remission can help enhance, is sometimes referred to as recovery capital. Also consistent with other studies was that younger individuals may have been more likely to drop out of treatment prematurely compared to older individuals. This is likely a reflection of how common drinking and other drug use is among young adults, and in parallel, young adults’ lower levels of motivation to initiate and sustain recovery, on average, compared to older adults.

Regarding age, the youngest parents had the highest rates of referral to treatment (Younger than 20, 64%; 21-30, 60%; 31-40, 58%; 40 or older, 55%). Among those who entered treatment, however, the youngest parents were least likely to complete it (Younger than 20, 44%; 21-30, 52%, 31-40, 56%, 40 or older, 60%).

More research is needed, but this is a positive first step showing that it may be possible to facilitate treatment engagement and increase recovery rates by using the child welfare system as a primary referral source.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

About 12% of children under 18 live with a parent who has an substance use disorder (SUD). Substance misuse is an important risk factor for child maltreatment (see here).

Parents who misuse substances may be referred to the child welfare system due to impaired ability to adequately care for, or respect the rights of, their child. This offers an opportunity to engage them in treatment.

The Child Protection Substance Abuse Initiative is a pilot program in New Jersey where individuals with suspected substance misuse are referred to an addiction specialist counselor for an substance use disorder (SUD) assessment directly within the Division of Child Protection. This study is important because it will provide insight on the potential utility of this type of collaborative program & this model could be applied in other states.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- There are several limitations to this program evaluation study. First, individuals were not randomized into the program. So we cannot be certain that the program strategies caused individuals to enter into treatment.

- Second, as the study took place in one state, it is unclear whether these results might generalize to child welfare programs in other states.

- Third, although an assessment was conducted and referral to treatment was provided as needed, there were no data on the clinical profiles of the participants. Therefore, we cannot determine the severity of the participants’ substance use or whether clients met formal clinical diagnostic criteria for substance use disorder (SUD) (i.e., based on the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders; DSM). This further limits the ability to determine whether these results generalize to other individuals in child welfare programs across the country.

- Fourth, there appeared to be several programs to which individuals were referred, but the program characteristics were not described in detail (e.g., level of care and services offered). Some programs may have been more effective at retaining individuals than others; however, the lack of data on program type does not allow for this type of analysis.

- Finally, although it is known whether an individual completed treatment, data were not provided on actual substance use outcomes. Thus, the true effectiveness of the program, even in this particular sample of clients, remains somewhat unclear.

NEXT STEPS

A study that randomizes child welfare clients to receive the intensive assessment and treatment linkage intervention described here or be put on a waitlist, and compares substance use outcomes may help better estimate the true effectiveness of this intervention.

If shown to be helpful using this type of study design, it would make a more compelling case to roll out this innovative approach to other states as well. As part of this more rigorous study, it might also be interesting to see if recovery coaching during treatment (not just to help link individuals to treatment) might help address any special barriers faced by minorities, thereby increasing the likelihood that they will successfully complete treatment.

Finally, future research might investigate, for participants with older children/adolescents, whether the children have improved psychosocial outcomes as a result of their parents receiving substance use disorder (SUD) treatment (e.g., improved academic performance and decreased aggressive behavior).

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: You might be able to enter treatment and recovery through the child welfare system, though more research is needed to determine how to maximize your likelihood of a successful outcome.

- For scientists: This study had several methodological limitations making it difficult to determine the effectiveness of this intervention. However, given the need for innovative approaches to engage more individuals in treatment, this interesting study suggests further investigation is warranted.

- For policy makers: Using the child welfare system to help engage individuals with substance use disorder treatment may prove to be a cost-effective and novel way to address the burden of substance use disorder (SUD) on communities and families including children. However, far more research is needed to examine the most effective strategies to accomplish this.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Individuals may enter your treatment program/system initially through the child welfare system. This study describes a promising approach to help facilitate this treatment entry, though more research is needed. One noteworthy finding is the reduced likelihood that African American patients will complete treatment. Innovative approaches, such as peer recovery coaches, may help address barriers to staying in treatment, but more research is also needed to study this hypothesis.

CITATIONS

Traube, D. E., He, A. S., Zhu, L., Scalise, C., & Richardson, T. (2015). Predictors of Substance Abuse Assessment and Treatment Completion for Parents Involved with Child Welfare: One State’s Experience in Matching across Systems. Child Welfare, 94(5), 45-66.