Quality of Life Differences? Compulsorily vs. Voluntary Admittance to Addiction Treatment

Substance use disorder (SUD) treatment is traditionally deemed successful when the patient achieves full remission from the disorder. While this is an accomplishment worthy of celebration, it is also important to assess markers of success in other domains such as social functioning and personal health.

Quality of life (QoL) provides a subjective metric of overall well-being, an important indicator for evaluating recovery since QoL improvements are likely to help patients sustain short-term changes in substance use in the long run (see Kelly and Hoeppner 2015).

Quality of Life (QoL) is lower in individuals with substance use disorders (SUD) than compared to other chronic psychiatric conditions or no substance use disorder at all.

In Norway, under the Municipal Health Care Act, non-psychotic adults with substance use disorder (SUD) can be involuntarily admitted to treatment for up to 3 months if their health is still at risk after exhaustive voluntary efforts. This raises the question of how quality of life (QoL) changes for compulsorily admitted (CA) patients after discharge relative to those who enter treatment voluntarily.

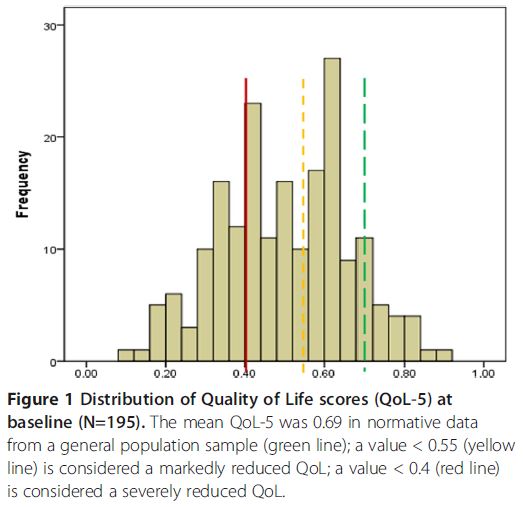

Pasareanu and colleagues evaluated quality of life (QoL) at baseline (treatment admission) and 6-months post-discharge for both compulsorily admitted (CA) (n = 65) and voluntarily admitted (VA) (n = 137) inpatients recruited from three publicly funded treatment centers in Norway. QoL was measured using a generic instrument (QoL-5) which measures satisfaction with life in general (i.e., not disease specific). This instrument covers physical and mental health, quality of relationships (with both a partner and friends), and existential QoL (relationship with oneself). Scores for each domain (health, relationships, and existential QoL) range from 0.1 (worst) to 0.9 (best) and are averaged for an overall score.

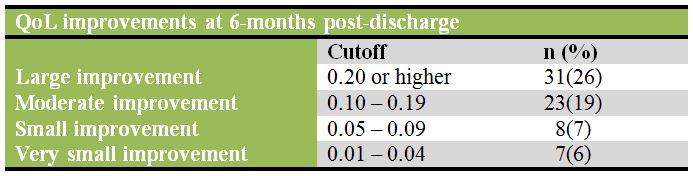

To measure increases in quality of life (QoL) following treatment, QoL score change was calculated by subtracting QoL at baseline from QoL at 6-month follow-up; positive scores signified improvement. Of the 202 participants at baseline, 123 (61%) were reached at follow-up. Due to lack of resources, study staff focused outreach efforts on compulsorily admitted (CA) patients since this population was central to the research question. Thus, significantly more CA patients (82% vs. 59% of voluntarily admitted (VA)) were reached at follow-up, though there were no differences in demographics, severity scores, or length of stay between those reached at follow-up and those not reached.

Participants were 34% female with an average age of 30 years, and all met ICD-10 criteria for substance use disorder (SUD) (83% with drug use disorder).

Using multivariate logistic regression, the authors found evidence for female gender as a predictor of having a large improvement (≥0.2) in quality of life (QoL); the odds of having a large improvement in QoL were 2.64 times higher for females than males (Odds Ratio: 2.64, 95% CI: 1.12-6.22). Somewhat counter-intuitively, neither number of days in treatment nor abstinence at treatment discharge were significantly associated with QoL.

IN CONTEXT

Since patients with substance use disorder (SUD) have a quality of life (QoL) as low or lower than patients with other chronic diseases, this is an important outcome to measure for recovery.

The authors found no differences between quality of life (QoL) for voluntarily admitted (VA) and compulsorily admitted (CA) participants which may be explained by integrated treatment of the two groups. By comparison, in the U.S., compulsorily admitted (CA) patients tend to have slightly better outcomes possibly because they are retained in treatment longer.

However, this study did not find an association between quality of life (QoL) and length of stay or abstinence, which highlights the importance of measuring QoL in addition to these other variables.

Additionally, in another Scandinavian country, Sweden, where treatment for voluntarily admitted (VA) and compulsorily admitted (CA) patients is separated, studies failed to find a difference in outcome between groups. More research is needed to determine the mechanism behind quality of life (QoL) improvements, which may be related to structural characteristics of the treatment facilities or factors inherent to the patient population.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Recovery can be measured in many ways. Quality of life (QoL) is particularly important for gaining an overall picture of progress after finishing treatment, and for providing motivating reinforcers for continued recovery efforts.

- For scientists: QoL in addiction research is still limited. Some important questions are how leaving treatment against medical advice impacts QoL and if QoL improvements differ between public and private facilities. Also, moderators of gains in QoL (e.g., gender, addiction severity, psychiatric and medical comorbidities) need to be tested in larger samples with better follow-up rates. Since this present study did not include a comparison group, it is important to study changes in the outcome among individuals with SUD who did not receive treatment.

- For policy makers: Patient-centered outcomes are becoming increasingly important to the field. Outcomes such as QoL should be supported in research as they provide more information beyond the traditional objective outcomes such as abstinence.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Measuring how your patient is doing in areas of their life besides the condition for which they are being treated can provide valuable information on their progress and adjustment in recovery process.

CITATIONS

Pasareanu, A. R., Opsal, A., Vederhus, J. K., Kristensen, Ø., & Clausen, T. (2015). Quality of life improved following in-patient substance use disorder treatment. Health and quality of life outcomes, 13(1), 35.