Predictors of Addiction & Mental Health Treatment Among New Arrestees

The U.S. has the highest incarceration rate in the world with over 2 million people in prison.

Of adult offenders, as many as three quarters have a substance use disorder (SUD) and about half suffer from other mental health problems. Despite the need for treatment, treatment utilization rates are low for individuals prior to entering the criminal justice system.

Additionally, there are known disparities in access to treatment for these individuals.

Criminal justice issues are often cyclical with high rates of re-arrest, diminishing the ability of individuals to seek and prioritize behavioral health treatment when not incarcerated.

Hunt, Peters, and Kremling examined utilization rates of mental health treatment, SUD treatment, and combined SUD/mental health treatment among 18,421 male arrestees between 2007 and 2010 in metropolitan jails in 10 U.S. cities (Atlanta, Charlotte, Chicago, Denver, Indianapolis, Minneapolis, New York, Portland, Sacramento, and Washington, D.C.).

The goal of the study was to explore relationships between treatment history and patient characteristics including sociodemographic variables, substance use, and substance use severity.

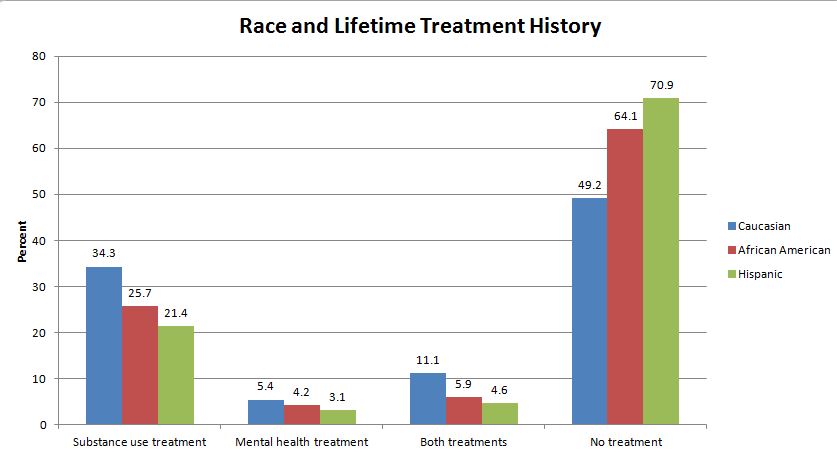

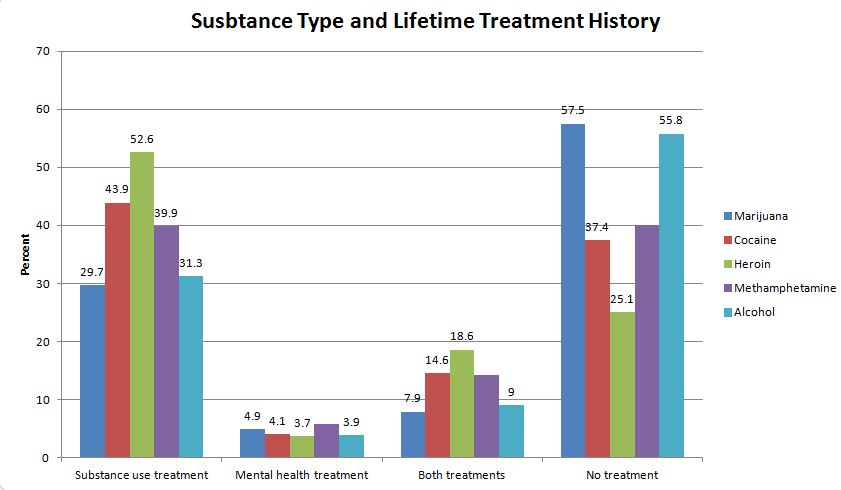

The data was derived from the Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring II (ADAM II) program which used probability-based sampling to draw a representative sample based on age, race/ethnicity, and offense type. Participants were recruited and interviewed within 24 hours of booking. The average participant was 34 years old and had about 13 prior arrests. Participants were 52% African American, 27% Caucasian, and 22% Hispanic. Over 60% had received no prior treatment while 27% received prior SUD treatment, 4% received prior mental health treatment, and 7% had previously received both types of treatment. Alcohol (52%), marijuana (51%), and cocaine (22%) were the most commonly used substances in the past year.

The authors examined predictors of receiving behavioral health treatment (i.e., treatment for mental health, SUD, or both) finding that older age, Caucasian race, frequent prior arrests, cocaine and heroin use, and more severe alcohol or other drug problems were associated with higher likelihood of receiving any type of treatment, both treatments, or SUD treatment alone, while those with a 4-year college degree were less likely to have received any type of treatment in the past.

IN CONTEXT

This study highlights the extent to which arrested individuals in need of behavioral health treatment underutilize services.

One of the more important findings from this study is the racial disparities in behavioral health treatment utilization.

African Americans were less likely to engage in care and both African Americans and Latinos were less likely to benefit from SUD treatment in terms of reduced subsequent likelihood of arrest in comparison to Caucasians. This shows the extent to which a treatment disparity can impact criminal justice involvement for minorities.

The cause of this racial disparity is complex but may be a combination of factors such as geographic proximity to services and inadequate (or lack of) health insurance. A majority of participants in the current study had no history of prior treatment.

Most prisons lack the services to properly treat these individuals, creating a missed opportunity for care. This lack of focus on what may be the primary drivers of the criminal behavior (i.e., substance use/mental health problems) may lead to more rapid recidivism.

Since availability of treatment or motivation to engage in care in the community appears to be lacking, prisons could serve as a location to help individuals in need of substance use or mental health services. Rather than returning people to the same environment without addressing their needs, staff could work with prisoners to develop recovery-oriented skills and connect them to continuing care upon release.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- A major limitation of this study is that the sample only included males so it is unknown if the results are generalizable to female arrestees.

- Additionally, this sample is representative of the population of metropolitan jails so results may not apply to other settings.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: There may be more barriers to minorities finding adequate services for your behavioral health issue.

- For scientists: Research is needed on how to best develop and integrate treatment services into prisons since treatment may help reduce the rate of recidivism for people whose behavioral health issues influence their criminal activity.

- For policy makers: Low rates of treatment utilization prior to arrest among prisoners with mental health and substance use issues shows the need for expanding services to jails and prisons and for greater provision of services at earlier stages of criminal involvement (e.g., while on probation).

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Treating incarcerated patients can be difficult. In the event of a patient’s release or transfer to another facility, it is important to ensure continuity of quality care.

CITATIONS

Hunt, E., Peters, R. H., & Kremling, J. (2015). Behavioral health treatment history among persons in the justice system: Findings from the Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring II Program. Psychiatr Rehabil J, 38(1), 7-15. doi: 10.1037/prj0000132