There is high co-occurrence of debilitating pain for those in substance use disorder treatment. The current study examined the prevalence and characteristics of treatment facilities tailored also to address chronic pain.

There is high co-occurrence of debilitating pain for those in substance use disorder treatment. The current study examined the prevalence and characteristics of treatment facilities tailored also to address chronic pain.

l

Chronic pain, defined as long-term pain persisting beyond a “typical” recovery period, is common among people in the United States. Approximately 20% reporting some degree of current chronic pain and around 7% report high impact chronic pain, which is pain that substantially restricts activities of daily living. Chronic pain is especially common among those seeking treatment for substance use disorder, with studies suggesting that approximately 60% of those with opioid use disorder report chronic pain. Chronic pain can both result in, and result from or become exacerbated by, substance use.

Some report using substances to cope with physical or emotional turmoil from chronic pain or developing an opioid use disorder when receiving a prescription for chronic pain. However, prolonged substance use can also lead to pain through substance-related injuries or alcohol-related neuropathy. Prolonged use of analgesic pain medications – both prescribed and non-prescribed – can also worsen pain over the long term through the downregulation of opioid receptors. Regardless of the pathway, it is clear that for many, chronic pain commonly intersects with substance use and may act as a barrier to initiating and sustaining recovery. Engaging with pain care can be challenging for this population due to lower access to care, fear, and stigma related to discrimination. Treatment of co-occurring pain and substance use disorder simultaneously may improve treatment and recovery outcomes. However, it is unclear how common such co-occurring treatment is in the United States. The current study examined the prevalence and characteristics of treatment facilities tailored for people with chronic pain and substance use disorders.

This was a secondary analysis of cross-sectional, publicly available data from SAMHSA’s 2019 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services. Curated by the United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the survey is an annual census of the locations, structure, services, and service utilization of treatments facilities serving people with substance use disorders and co-occurring conditions. Only data from the 2019 survey was used as this was the first year that data on co-occurring pain was collected. Sent to a total of 19,795 facilities, responses were collected between March 29 and December 17, 2019. Facilities could respond via telephone, mail, or online questionnaire. Only 17,808 were eligible for the survey, and 90% of these were included in the report, with a total of 15,961 responses.

The facilities reported whether they offered a substance use disorder treatment program or group specifically tailored for clients with co-occurring pain and substance use. The researchers examined program factors associated with whether the facilities had programming specifically for clients with co-occurring pain and substance use. They first tested each program variable on its own. Then for each program variable associated with offering concomitant pain care, analyses examined all of these variables at once. This helps isolate the effect of each variable, controlling for other factors that could be explaining the effect, to allow for potentially stronger inferences that the variable is causally related to the presence of pain care in the treatment program.

Specifically the study examined the following facility characteristics as predictors: organization type (e.g., private, for-profit, government), comprehensive assessment or diagnosis services, programs tailored for veterans, hospital inpatient services, residential treatment services, whether the facility only serves patients with opioid use disorder, methadone or buprenorphine services, any form of accreditation, accredited by the Joint commissions, whether the facility accepts health insurance, Medicaid, or Medicare, whether the facility receives government funding, and whether the facility is a hospital or operated by a hospital. The researchers included all variables in a single model adjusting for all other variables to identify the best predictors of having tailored programming for co-occurring pain and substance use disorder.

Prevalence of and factors associated with increased likelihood of having co-occurring pain and substance use disorder programming.

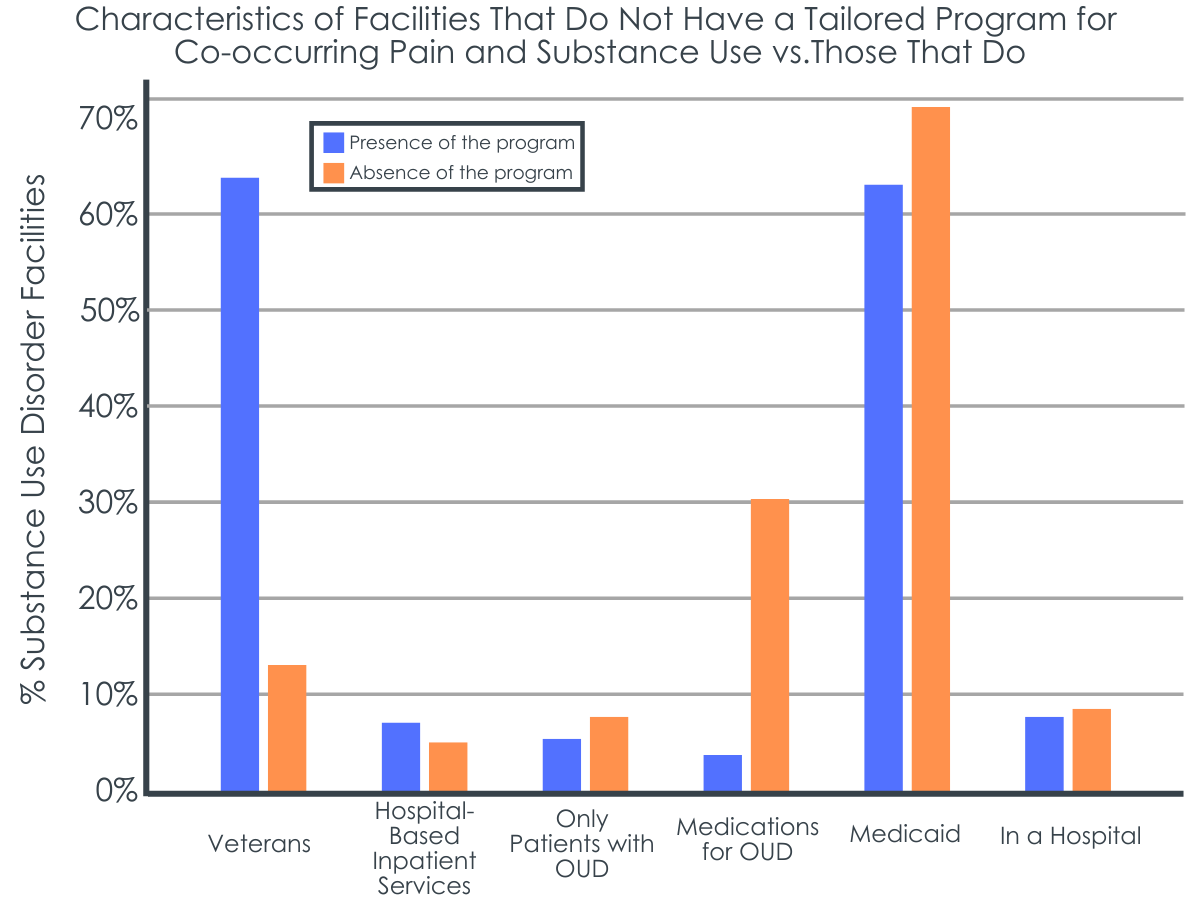

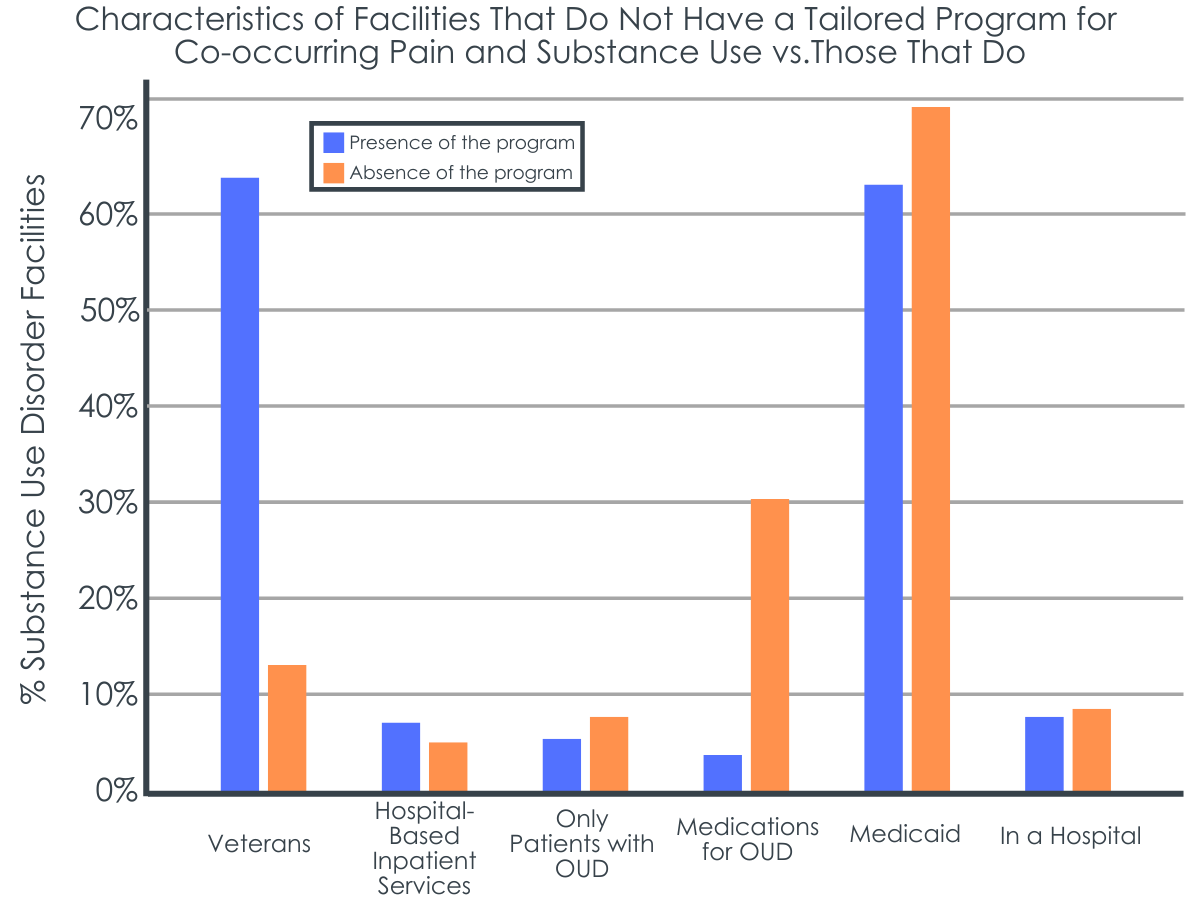

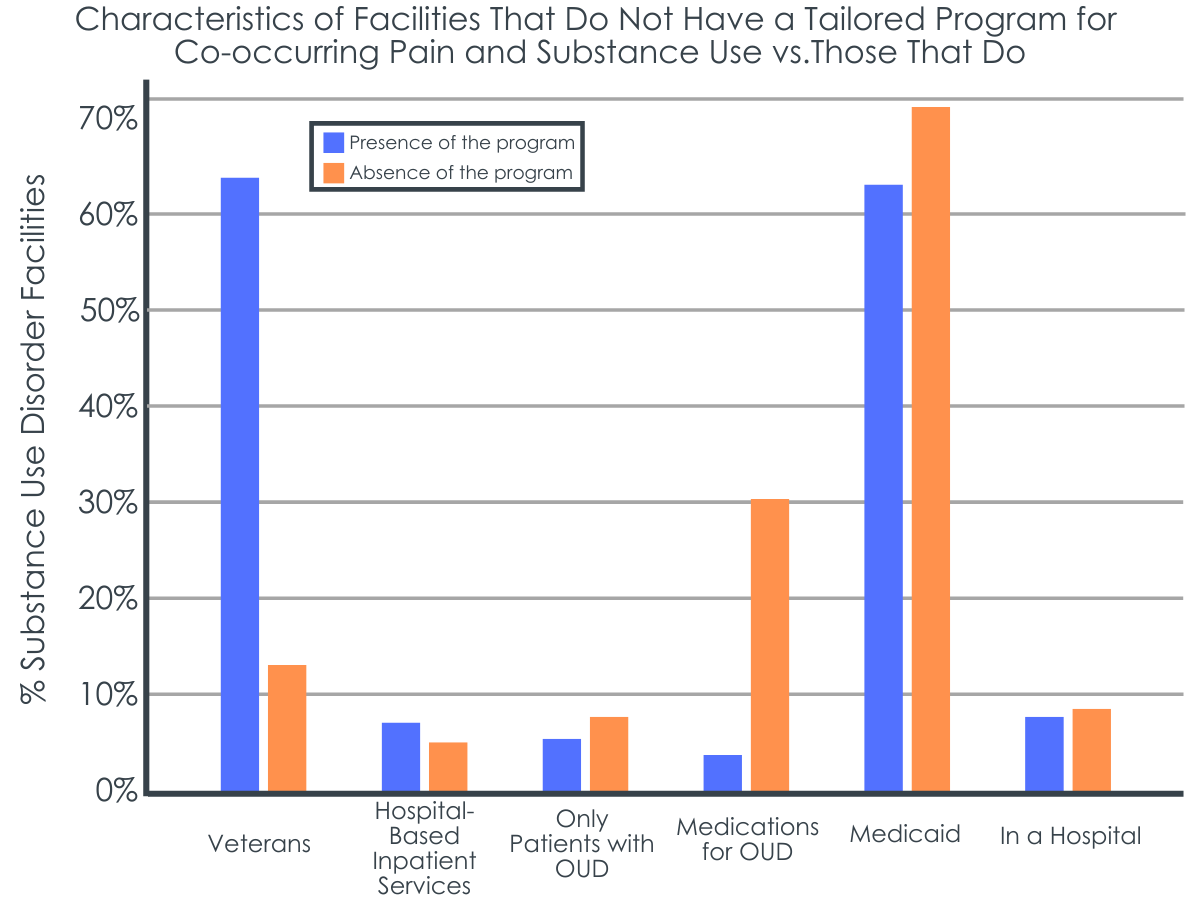

Of the facilities providing data, 2,990 (18.8%) reported having a tailored program for co-occurring pain and substance use disorder. Facilities that reported having tailored programs for veterans (10.2 times more likely), offering hospital-based inpatient treatment services (1.8 times more likely), serving only clients with opioid use disorder (17.2 times more likely), and providing medications for opioid use disorder (1.77 times more likely) were more likely to have a tailored program for co-occurring pain and substance use disorder.

Factors associated with decreased likelihood of having co-occurring pain and substance use disorder programming.

Facilities accepting Medicaid as source of payment for substance use disorder treatment, however, were less likely to have programming tailored for people with co-occurring pain and substance use disorder (OR = 0.58; about half as likely). Further, facilities that were in a hospital or operated by a hospital were also less likely to have programming tailored for people with co-occurring pain and substance use disorder (OR = 0.41; about half as likely).

Despite high rates of comorbidity among its patients, the vast majority (more than 4 in 5) of substance use treatment facilities do not contain specific programming tailored for co-occurring pain and substance use disorder. As a result, such facilities may not be addressing a critical factor that can lead to a recurrence of use, return of symptoms, or reinstatement of substance use disorder. Rates of return to use are high even among people receiving treatment for substance use disorder. Yet, there are efficacious non-opioid treatments for pain, including physical therapy, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Including programming to address pain may be relatively “low hanging fruit” to improve treatment outcomes.

Facilities serving specific patients in which pain commonly occurs may be more likely to offer pain management care as part of their substance use treatment programming. For example, facilities that serve veteran populations were 10 times more likely to offer pain treatment. There also appears to be recognition that pain is important to address among facilities serving patients with opioid use disorders. This is likely driven by the close connection between the role of opioids as an analgesic amidst the historic backdrop of the first wave of the opioid epidemic, which primarily consisted of over-prescription of opioids by medical providers. However, there is an emerging twin epidemic of methamphetamine and opioids (i.e., the fourth wave of the opioid epidemic), and rates of co-occurring methamphetamine and opioid use disorder are increasingly common. Such facilities that serve only patients with an exclusive opioid use disorder may exclude patients with other co-occurring substance use disorders. Further, pain exists in the context of other substance use disorder, and there is some evidence that including tailored programming for such comorbidity can lead to greater retention in treatment and reductions in pain and substance use.

The fact that facilities accepting Medicaid as payment for services were less likely to have programming specifically tailored for people with pain and substance use disorders may be explained by barriers to providing this additional resource, perhaps due to additional costs, lack of access to necessary treatments, lack of personnel, practice knowledge, or practice beliefs. Regardless, this gap in care for people in lower income brackets that would be more likely to use Medicaid for health insurance represents a social determinant of health that may drive growing health disparities.

It is unclear why facilities in a hospital would be less likely to have such services, particularly since the opposite effect was found for facilities offering inpatient treatment services. This may be due to a specificity effect: facilities more specifically focused on treatment for substance use disorder may have to provide tailored treatments themselves, whereas facilities within hospitals may be able to refer to other departments for patients needing simultaneous pain management in addition to substance use disorder care.

Despite the fact that chronic pain is common among people with substance use disorders, less than 1 in every 5 substance use disorder treatment facilities provide specific programming for co-occurring substance use disorder and chronic pain. Facilities serving veterans, people with opioid use disorder including those receiving medications to prevent opioid use, or those receiving inpatient services are more likely to address co-occurring pain, where facilities that accept Medicaid or that are located in or operated by a hospital are less likely to address co-occurring substance use disorder and pain. While the cross-sectional design of this study does not allow for direct causal connections to be made between program characteristics like these and the provision of pain management, they are important markers of programs that are more or less likely to offer combined substance use and pain care for those who need it.

Ramdin, C., Attaalla, K., Ghafoor, N., & Nelson, L. (2023). Factors Associated With the Presence of Co-occurring Pain and Substance Use Disorder Programs in Substance Use Treatment Facilities. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 17(2), e72-e77. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000001051

l

Chronic pain, defined as long-term pain persisting beyond a “typical” recovery period, is common among people in the United States. Approximately 20% reporting some degree of current chronic pain and around 7% report high impact chronic pain, which is pain that substantially restricts activities of daily living. Chronic pain is especially common among those seeking treatment for substance use disorder, with studies suggesting that approximately 60% of those with opioid use disorder report chronic pain. Chronic pain can both result in, and result from or become exacerbated by, substance use.

Some report using substances to cope with physical or emotional turmoil from chronic pain or developing an opioid use disorder when receiving a prescription for chronic pain. However, prolonged substance use can also lead to pain through substance-related injuries or alcohol-related neuropathy. Prolonged use of analgesic pain medications – both prescribed and non-prescribed – can also worsen pain over the long term through the downregulation of opioid receptors. Regardless of the pathway, it is clear that for many, chronic pain commonly intersects with substance use and may act as a barrier to initiating and sustaining recovery. Engaging with pain care can be challenging for this population due to lower access to care, fear, and stigma related to discrimination. Treatment of co-occurring pain and substance use disorder simultaneously may improve treatment and recovery outcomes. However, it is unclear how common such co-occurring treatment is in the United States. The current study examined the prevalence and characteristics of treatment facilities tailored for people with chronic pain and substance use disorders.

This was a secondary analysis of cross-sectional, publicly available data from SAMHSA’s 2019 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services. Curated by the United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the survey is an annual census of the locations, structure, services, and service utilization of treatments facilities serving people with substance use disorders and co-occurring conditions. Only data from the 2019 survey was used as this was the first year that data on co-occurring pain was collected. Sent to a total of 19,795 facilities, responses were collected between March 29 and December 17, 2019. Facilities could respond via telephone, mail, or online questionnaire. Only 17,808 were eligible for the survey, and 90% of these were included in the report, with a total of 15,961 responses.

The facilities reported whether they offered a substance use disorder treatment program or group specifically tailored for clients with co-occurring pain and substance use. The researchers examined program factors associated with whether the facilities had programming specifically for clients with co-occurring pain and substance use. They first tested each program variable on its own. Then for each program variable associated with offering concomitant pain care, analyses examined all of these variables at once. This helps isolate the effect of each variable, controlling for other factors that could be explaining the effect, to allow for potentially stronger inferences that the variable is causally related to the presence of pain care in the treatment program.

Specifically the study examined the following facility characteristics as predictors: organization type (e.g., private, for-profit, government), comprehensive assessment or diagnosis services, programs tailored for veterans, hospital inpatient services, residential treatment services, whether the facility only serves patients with opioid use disorder, methadone or buprenorphine services, any form of accreditation, accredited by the Joint commissions, whether the facility accepts health insurance, Medicaid, or Medicare, whether the facility receives government funding, and whether the facility is a hospital or operated by a hospital. The researchers included all variables in a single model adjusting for all other variables to identify the best predictors of having tailored programming for co-occurring pain and substance use disorder.

Prevalence of and factors associated with increased likelihood of having co-occurring pain and substance use disorder programming.

Of the facilities providing data, 2,990 (18.8%) reported having a tailored program for co-occurring pain and substance use disorder. Facilities that reported having tailored programs for veterans (10.2 times more likely), offering hospital-based inpatient treatment services (1.8 times more likely), serving only clients with opioid use disorder (17.2 times more likely), and providing medications for opioid use disorder (1.77 times more likely) were more likely to have a tailored program for co-occurring pain and substance use disorder.

Factors associated with decreased likelihood of having co-occurring pain and substance use disorder programming.

Facilities accepting Medicaid as source of payment for substance use disorder treatment, however, were less likely to have programming tailored for people with co-occurring pain and substance use disorder (OR = 0.58; about half as likely). Further, facilities that were in a hospital or operated by a hospital were also less likely to have programming tailored for people with co-occurring pain and substance use disorder (OR = 0.41; about half as likely).

Despite high rates of comorbidity among its patients, the vast majority (more than 4 in 5) of substance use treatment facilities do not contain specific programming tailored for co-occurring pain and substance use disorder. As a result, such facilities may not be addressing a critical factor that can lead to a recurrence of use, return of symptoms, or reinstatement of substance use disorder. Rates of return to use are high even among people receiving treatment for substance use disorder. Yet, there are efficacious non-opioid treatments for pain, including physical therapy, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Including programming to address pain may be relatively “low hanging fruit” to improve treatment outcomes.

Facilities serving specific patients in which pain commonly occurs may be more likely to offer pain management care as part of their substance use treatment programming. For example, facilities that serve veteran populations were 10 times more likely to offer pain treatment. There also appears to be recognition that pain is important to address among facilities serving patients with opioid use disorders. This is likely driven by the close connection between the role of opioids as an analgesic amidst the historic backdrop of the first wave of the opioid epidemic, which primarily consisted of over-prescription of opioids by medical providers. However, there is an emerging twin epidemic of methamphetamine and opioids (i.e., the fourth wave of the opioid epidemic), and rates of co-occurring methamphetamine and opioid use disorder are increasingly common. Such facilities that serve only patients with an exclusive opioid use disorder may exclude patients with other co-occurring substance use disorders. Further, pain exists in the context of other substance use disorder, and there is some evidence that including tailored programming for such comorbidity can lead to greater retention in treatment and reductions in pain and substance use.

The fact that facilities accepting Medicaid as payment for services were less likely to have programming specifically tailored for people with pain and substance use disorders may be explained by barriers to providing this additional resource, perhaps due to additional costs, lack of access to necessary treatments, lack of personnel, practice knowledge, or practice beliefs. Regardless, this gap in care for people in lower income brackets that would be more likely to use Medicaid for health insurance represents a social determinant of health that may drive growing health disparities.

It is unclear why facilities in a hospital would be less likely to have such services, particularly since the opposite effect was found for facilities offering inpatient treatment services. This may be due to a specificity effect: facilities more specifically focused on treatment for substance use disorder may have to provide tailored treatments themselves, whereas facilities within hospitals may be able to refer to other departments for patients needing simultaneous pain management in addition to substance use disorder care.

Despite the fact that chronic pain is common among people with substance use disorders, less than 1 in every 5 substance use disorder treatment facilities provide specific programming for co-occurring substance use disorder and chronic pain. Facilities serving veterans, people with opioid use disorder including those receiving medications to prevent opioid use, or those receiving inpatient services are more likely to address co-occurring pain, where facilities that accept Medicaid or that are located in or operated by a hospital are less likely to address co-occurring substance use disorder and pain. While the cross-sectional design of this study does not allow for direct causal connections to be made between program characteristics like these and the provision of pain management, they are important markers of programs that are more or less likely to offer combined substance use and pain care for those who need it.

Ramdin, C., Attaalla, K., Ghafoor, N., & Nelson, L. (2023). Factors Associated With the Presence of Co-occurring Pain and Substance Use Disorder Programs in Substance Use Treatment Facilities. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 17(2), e72-e77. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000001051

l

Chronic pain, defined as long-term pain persisting beyond a “typical” recovery period, is common among people in the United States. Approximately 20% reporting some degree of current chronic pain and around 7% report high impact chronic pain, which is pain that substantially restricts activities of daily living. Chronic pain is especially common among those seeking treatment for substance use disorder, with studies suggesting that approximately 60% of those with opioid use disorder report chronic pain. Chronic pain can both result in, and result from or become exacerbated by, substance use.

Some report using substances to cope with physical or emotional turmoil from chronic pain or developing an opioid use disorder when receiving a prescription for chronic pain. However, prolonged substance use can also lead to pain through substance-related injuries or alcohol-related neuropathy. Prolonged use of analgesic pain medications – both prescribed and non-prescribed – can also worsen pain over the long term through the downregulation of opioid receptors. Regardless of the pathway, it is clear that for many, chronic pain commonly intersects with substance use and may act as a barrier to initiating and sustaining recovery. Engaging with pain care can be challenging for this population due to lower access to care, fear, and stigma related to discrimination. Treatment of co-occurring pain and substance use disorder simultaneously may improve treatment and recovery outcomes. However, it is unclear how common such co-occurring treatment is in the United States. The current study examined the prevalence and characteristics of treatment facilities tailored for people with chronic pain and substance use disorders.

This was a secondary analysis of cross-sectional, publicly available data from SAMHSA’s 2019 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services. Curated by the United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the survey is an annual census of the locations, structure, services, and service utilization of treatments facilities serving people with substance use disorders and co-occurring conditions. Only data from the 2019 survey was used as this was the first year that data on co-occurring pain was collected. Sent to a total of 19,795 facilities, responses were collected between March 29 and December 17, 2019. Facilities could respond via telephone, mail, or online questionnaire. Only 17,808 were eligible for the survey, and 90% of these were included in the report, with a total of 15,961 responses.

The facilities reported whether they offered a substance use disorder treatment program or group specifically tailored for clients with co-occurring pain and substance use. The researchers examined program factors associated with whether the facilities had programming specifically for clients with co-occurring pain and substance use. They first tested each program variable on its own. Then for each program variable associated with offering concomitant pain care, analyses examined all of these variables at once. This helps isolate the effect of each variable, controlling for other factors that could be explaining the effect, to allow for potentially stronger inferences that the variable is causally related to the presence of pain care in the treatment program.

Specifically the study examined the following facility characteristics as predictors: organization type (e.g., private, for-profit, government), comprehensive assessment or diagnosis services, programs tailored for veterans, hospital inpatient services, residential treatment services, whether the facility only serves patients with opioid use disorder, methadone or buprenorphine services, any form of accreditation, accredited by the Joint commissions, whether the facility accepts health insurance, Medicaid, or Medicare, whether the facility receives government funding, and whether the facility is a hospital or operated by a hospital. The researchers included all variables in a single model adjusting for all other variables to identify the best predictors of having tailored programming for co-occurring pain and substance use disorder.

Prevalence of and factors associated with increased likelihood of having co-occurring pain and substance use disorder programming.

Of the facilities providing data, 2,990 (18.8%) reported having a tailored program for co-occurring pain and substance use disorder. Facilities that reported having tailored programs for veterans (10.2 times more likely), offering hospital-based inpatient treatment services (1.8 times more likely), serving only clients with opioid use disorder (17.2 times more likely), and providing medications for opioid use disorder (1.77 times more likely) were more likely to have a tailored program for co-occurring pain and substance use disorder.

Factors associated with decreased likelihood of having co-occurring pain and substance use disorder programming.

Facilities accepting Medicaid as source of payment for substance use disorder treatment, however, were less likely to have programming tailored for people with co-occurring pain and substance use disorder (OR = 0.58; about half as likely). Further, facilities that were in a hospital or operated by a hospital were also less likely to have programming tailored for people with co-occurring pain and substance use disorder (OR = 0.41; about half as likely).

Despite high rates of comorbidity among its patients, the vast majority (more than 4 in 5) of substance use treatment facilities do not contain specific programming tailored for co-occurring pain and substance use disorder. As a result, such facilities may not be addressing a critical factor that can lead to a recurrence of use, return of symptoms, or reinstatement of substance use disorder. Rates of return to use are high even among people receiving treatment for substance use disorder. Yet, there are efficacious non-opioid treatments for pain, including physical therapy, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Including programming to address pain may be relatively “low hanging fruit” to improve treatment outcomes.

Facilities serving specific patients in which pain commonly occurs may be more likely to offer pain management care as part of their substance use treatment programming. For example, facilities that serve veteran populations were 10 times more likely to offer pain treatment. There also appears to be recognition that pain is important to address among facilities serving patients with opioid use disorders. This is likely driven by the close connection between the role of opioids as an analgesic amidst the historic backdrop of the first wave of the opioid epidemic, which primarily consisted of over-prescription of opioids by medical providers. However, there is an emerging twin epidemic of methamphetamine and opioids (i.e., the fourth wave of the opioid epidemic), and rates of co-occurring methamphetamine and opioid use disorder are increasingly common. Such facilities that serve only patients with an exclusive opioid use disorder may exclude patients with other co-occurring substance use disorders. Further, pain exists in the context of other substance use disorder, and there is some evidence that including tailored programming for such comorbidity can lead to greater retention in treatment and reductions in pain and substance use.

The fact that facilities accepting Medicaid as payment for services were less likely to have programming specifically tailored for people with pain and substance use disorders may be explained by barriers to providing this additional resource, perhaps due to additional costs, lack of access to necessary treatments, lack of personnel, practice knowledge, or practice beliefs. Regardless, this gap in care for people in lower income brackets that would be more likely to use Medicaid for health insurance represents a social determinant of health that may drive growing health disparities.

It is unclear why facilities in a hospital would be less likely to have such services, particularly since the opposite effect was found for facilities offering inpatient treatment services. This may be due to a specificity effect: facilities more specifically focused on treatment for substance use disorder may have to provide tailored treatments themselves, whereas facilities within hospitals may be able to refer to other departments for patients needing simultaneous pain management in addition to substance use disorder care.

Despite the fact that chronic pain is common among people with substance use disorders, less than 1 in every 5 substance use disorder treatment facilities provide specific programming for co-occurring substance use disorder and chronic pain. Facilities serving veterans, people with opioid use disorder including those receiving medications to prevent opioid use, or those receiving inpatient services are more likely to address co-occurring pain, where facilities that accept Medicaid or that are located in or operated by a hospital are less likely to address co-occurring substance use disorder and pain. While the cross-sectional design of this study does not allow for direct causal connections to be made between program characteristics like these and the provision of pain management, they are important markers of programs that are more or less likely to offer combined substance use and pain care for those who need it.

Ramdin, C., Attaalla, K., Ghafoor, N., & Nelson, L. (2023). Factors Associated With the Presence of Co-occurring Pain and Substance Use Disorder Programs in Substance Use Treatment Facilities. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 17(2), e72-e77. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000001051