2012 Estimates of Drug Use Disorders in the U.S.

The nature of drug use in the United States has changed over time.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

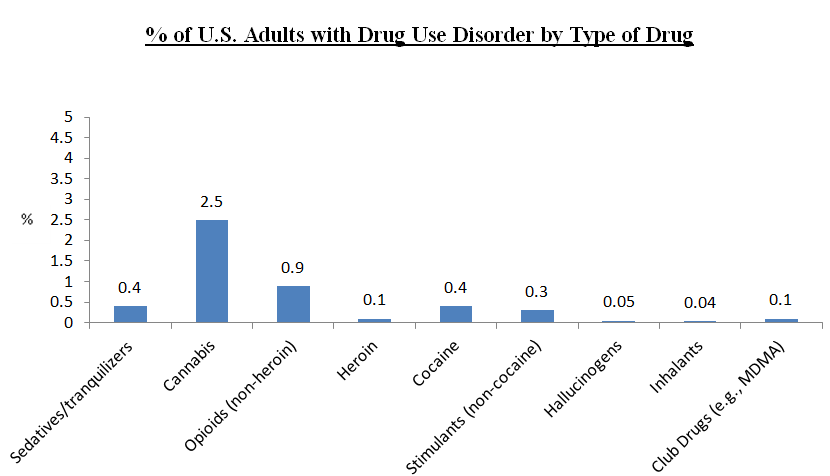

For example, while cocaine use is lower now than it was 10 years ago, non-medical use of prescription opioids and heroin use have increased during this time frame.

In addition, in May 2013, the American Psychiatric Association released a new edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), which resulted in changes in substance use disorder (SUD) terminology and diagnostic thresholds.

In contrast with DSM-IV, which categorized alcohol and other drug use disorders according to two distinct diagnostic categories, “abuse” and “dependence”, the current DSM-5 system has a single category of substance use disorder (SUD) consisting of 11 symptoms and divided by levels of severity within this category.

Click Here: Severity Levels of Substance Use Disorder Infographic

In contrast with the DSM-IV, DSM-5 SUD now includes an item that assesses for presence of craving (e.g., subjective feeling of need or strong desire for the drug) and has removed an item assessing continued use of the drug despite legal problems.

An epidemiological study of DSM-5 drug use disorders (DUDs), and rates of treatment seeking and relationships with other psychiatric disorders, among U.S. adults (18+years) using a geographically and demographically representative sample to estimate their current prevalence in the U.S. has not yet been conducted, a gap addressed by Grant and colleagues in this study.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III) assessed for substance use disorder (SUD) and other psychiatric disorders using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-5 (AUDADIS-5) in a sample of 36,000 adults, chosen to match the 2012 American Community Survey in terms of geographic locale and demographic characteristics.

Assessments were conducted in person, but with computer-assisted diagnostic interviews (i.e., there was a person on site but surveys were administered and data were collected electronically), and participants were paid $90 for participating in NESARC. Although not directly relevant to this study, it is worth mentioning saliva samples were also collected to facilitate genetic testing for future NESARC-based studies.

This study focused on the 12-month and lifetime prevalence of drug use disorders (DUDs) and how the presence of DUD is related to other substance use disorder (SUD) (including nicotine), psychiatric, and personality disorders. Disability for mental health, social functioning (i.e., the degree to which physical health or emotional problems interfered with social activities), and role emotional functioning (i.e., trouble doing work or other activities due to an emotional problem) were measured with the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

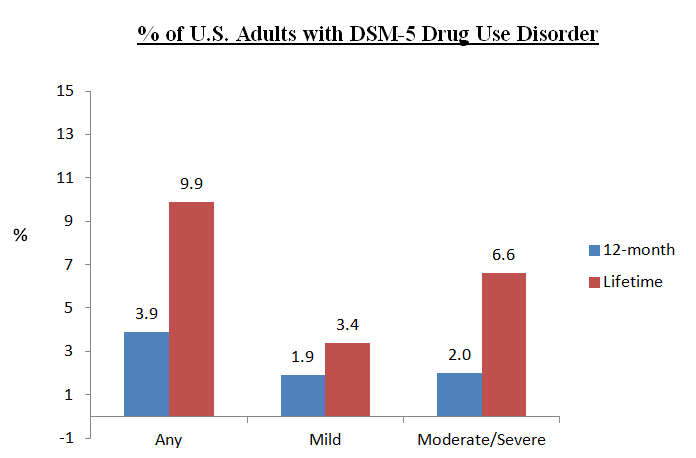

Overall, 4% of U.S. residents were diagnosed with current drug use disorder (DUD) (i.e., meeting criteria in the past 12 months), including 2% with mild, and 2% with moderate or severe, and 10% were diagnosed in their lifetime (i.e., meeting criteria during any year of their life).

Overall, individuals with drug use disorder (DUD) had poorer mental health, social functioning, and role emotional functioning than those without DUD, controlling statistically for demographic characteristics and other substance use disorders (SUDs) and psychiatric disorders. Regarding demographic differences, individuals who were male, 18-29 years old, Black or Native American, single, had a high school education or less, and incomes less than $20,000 per year had greater rates of DUD than individuals not in those demographic groups.

Regarding co-occurring substance use disorder (SUD) and other psychiatric disorders, those with drug use disorder (DUD) were 3x more likely to have alcohol use disorder (AUD), 3 times more likely to have nicotine use disorder, 2x more likely to have a mood disorder (e.g., major depressive or bipolar disorder), and 2 times more likely to have borderline personality disorder, adjusting for demographic characteristics and all other SUD and psychiatric disorders.

Although they were no more likely to have an anxiety disorder, those with drug use disorder (DUD) were 1.5x more likely to have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is also marked by anxiety symptoms (e.g., heightened physiological arousal in response to learned environmental cues), but is categorized as a trauma/stressor-related disorder, not an anxiety disorder, in the DSM-5. In general, having moderate or severe DUD carried greater risk for the presence of these co-occurring disorders than mild DUD (e.g., moderate/severe DUD were 2.2 times more likely to have PTSD, but mild DUD were no more likely to have PTSD than those without DUD).

This indicates relationships between drug use disorder (DUD) and co-occurring addiction/psychiatric disorders depend on (i.e., are moderated by) the level of severity.

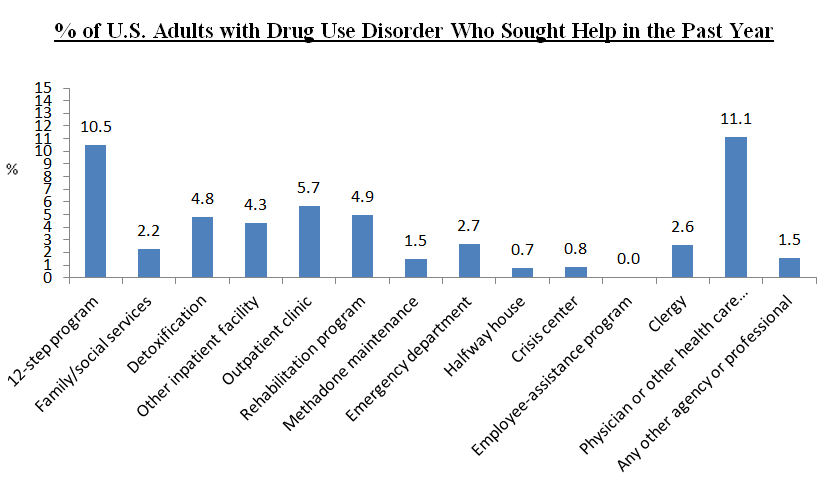

Individuals with moderate or severe DUD who sought help were most likely to do so through:

- a physician or other health care professional (e.g., primary care doctor)

- a 12-step mutual-help group

- an outpatient clinic

For those with drug use disorder (DUD sought help in the past year, which increased to 20% when only those with moderate or severe DUD were included.

Regarding treatment, although average age of onset for drug use disorder (DUD) (when the disorder first occurs for those who are diagnosed) is approximately age 24, those who seek treatment or non-professional services for their drug use disorder (DUD) do not do so until about 28 years old, a 4 year difference. For those with DUD,

It is important to first note that prevalence rates of drug use disorder (DUD) are more modest than those of alcohol use disorder (AUD). For example, about 14% of U.S. adults meet criteria for a current AUD (i.e., past 12 months) relative to just 4% for DUD (see here).

However, while likelihood of seeking treatment is higher for those with drug use disorder (DUD) than for alcohol use disorder (AUD) (14% vs. 8%), those with severe DUD and AUD demonstrated similar rates of treatment seeking. One implications may be that, at lower levels of severity, DUD leads to more distress, and/or gives rise to medical and psychological consequences that more clearly impact one’s functioning and motivation to seek professional help, while those with less severe AUD may be more difficult to engage in treatment.

Alternatively, these higher rates of treatment seeking at lower levels of severity for drug use disorder (DUD) may be because the majority of non-alcohol drug use is illegal in the U.S. If someone with less severe DUD is arrested for a crime related to drug use, for example, the criminal justice system may be a bridge to treatment for these individuals; indeed, the criminal justice system is a major referral source to substance use disorder (SUD) treatment in the U.S.

One important similarity between alcohol use disorder (AUD) and drug use disorder (DUD) is the elevated risk for likelihood of diagnosis in younger individuals (18-29), who have the highest 12-month rates of both types of substance use disorder (SUD). Both disorders surface around age 25, suggesting this 18-29 age range, sometimes referred to as emerging adulthood, is a particularly sensitive time for the development of life-impacting substance use.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

The study will help establish the prevalence of drug use disorders (DUDs) for adults in the U.S., and provide insight into risks for other psychiatric disorder among those with DUD. This type of epidemiological study can also identify particular sub-groups at risk for DUD, and rates of treatment seeking, to inform prevention and intervention approaches.

Although 20% of those with moderate or severe drug use disorder (DUD) sought help, this help-seeking covered a range of options, including but not limited to specialty addiction treatment or recovery support services. The extent to which individuals who reported help seeking through a physician, for example, may have received brief advice to quit, or a referral to specialty care, without receipt of any evidence-based treatment (e.g., medication assisted treatment for opioid use disorder, motivational interviewing for marijuana use disorder) or linkages to 12-step mutual-help groups.

This highlights a need for better understanding of the types of help received from these non-specialty settings, and a closer examination of the percent who receive specialty services.

For example, another large, nationally representative survey that used the older DSM-IV criteria, the SAMHSA National Survey on Drug Use and Health, found about 20% of those with any drug use disorder (DUD) received specialty addiction treatment, which excludes mutual-help groups and services received at a private doctor’s office. In other words, the SAMHSA survey suggests a greater percentage of individuals with drug use disorder (DUD) are getting help for their problem than this NESARC-III study.

It is possible that with the new DSM, which was used in the NESARC-III, more individuals will be identified as having drug use disorder (DUD), and potentially highlight greater need for availability and access to specialty services.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- As authors point out, these data are cross sectional (measured at one point in time), so the data cannot help us determine whether drug use disorder (DUD) causes co-occurring substance use disorder (SUD) and other psychiatric disorders or vice versa. In fact, we know that the relationship between DUD and other disorders is complex, as many people will have mood disorder or PTSD before developing a DUD; some after they develop DUDs. These data are descriptive and help identify how much more likely someone will meet criteria for one of these co-occurring disorders if a DUD is present.

NEXT STEPS

One possible next step is to examine whether help-seeking, in particular for specialty addiction treatment, differs by demographic characteristics, including gender, ethnicity, and age. This will help identify groups of individuals with particularly critical need for better strategies to increase motivation, and/or address practical barriers, to attend treatment.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: There is a 4 year lag, on average, between the time drug use begins to negatively affect someone’s life, and when they seek help. Other studies have shown that even after initially seeking treatment, it often takes many years before remission is achieved. We know from other studies on drug use disorder and substance use disorder more broadly, if you can shorten this length of time between when drugs begin negatively affecting ones life, and seeking treatment, you may be able to shorten how long it takes to achieve remission. Therefore, even if one is not ready to quit entirely, we suggest checking out treatment programs in your area to see if they have services that address personal treatment goals.

- For scientists: This study from the NESARC-III dataset provides the best estimate to date of DSM-5 drug use disorders.

- For policy makers: This study identified groups at particular risk of developing drug use disorder, including young adults, minorities, and those with lower levels of education. Strongly consider policies and funding for early intervention efforts to target these potentially vulnerable groups.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: For those providers in specialty addiction settings, individuals with drug use disorder are significantly more likely than those without drug use disorder to have co-occurring alcohol, mood, and personality disorders, as well as PTSD. Consider in-depth psychiatric evaluations to assess for the presence of these co-occurring disorders in order to adequately address all potential relapse risks and co-occurring illness in the treatment plan. For those in non-specialty medical and other health care settings, you are currently the most likely point of contact in the treatment system for someone with drug use disorder. If you/your staff are trained and equipped to provide evidence-based services, such as medication assisted treatments (e.g., buprenorphine/naloxone), motivational enhancement, and assertive linkages to specialty services when needed you are in better position to increase the likelihood of positive patient outcomes.

CITATIONS

Grant, B. F., Saha, T. D., Ruan, W. J., Goldstein, R. B., Chou, S. P., Jung, J., . . . Hasin, D. S. (2015). Epidemiology of DSM-5 Drug Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. JAMA Psychiatry, 1-9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2132