l

Many family-based psychosocial therapies have positive effects on opioid use disorder treatment outcomes. Given that medications (i.e. buprenorphine, methadone, naltrexone) are first-line treatment approaches for opioid use disorder, studies have also begun to identify new ways to incorporate family-based interventions into medication treatment programs to enhance treatment and recovery outcomes.

Such interventions have the potential to help overcome barriers to continuing medication treatment, and to promote sustained recovery. For example, promising interventions for adults have incorporated significant others to successfully engage their loved ones in treatment and medication adherence (e.g., Community Reinforcement and Family Training, or CRAFT). In addition, couples therapy aimed at building trust, compliance, and coping skills, as well as skills for crisis intervention and healthy communication between couples has shown to significantly reduce illicit drug use as well as family and social problems, relative to treatment as usual with methadone and individual counseling. Other research has demonstrated the positive effects of multi-family therapy during methadone treatment, which involves group meetings between families and patients with addiction to address communication and relationship aspects of family and substance use disorder, ultimately reducing addiction severity and improving social support more than treatment as usual. Despite the positive results of these studies, mixed outcomes are seen for a variety of interventions and patient groups. Many existing interventions are also time and resource intensive (e.g., multiple sessions, trained staff), limiting their reach to settings that already have many resources.

Additional research is needed to develop and test novel, briefer interventions that can be administered more easily in diverse treatment and recovery settings, including those with limited resources. Research in this area might ultimately identify cost-effective, low-barrier interventions that enhance treatment and promote continuing care for better recovery outcomes among individuals who are receiving medications to treat their opioid use disorder. This randomized controlled trial examined the effects of a new 3-session, family-based intervention on family functioning and patient opioid use during the early stages of opioid use disorder medication treatment, in a resource-limited medical setting in India.

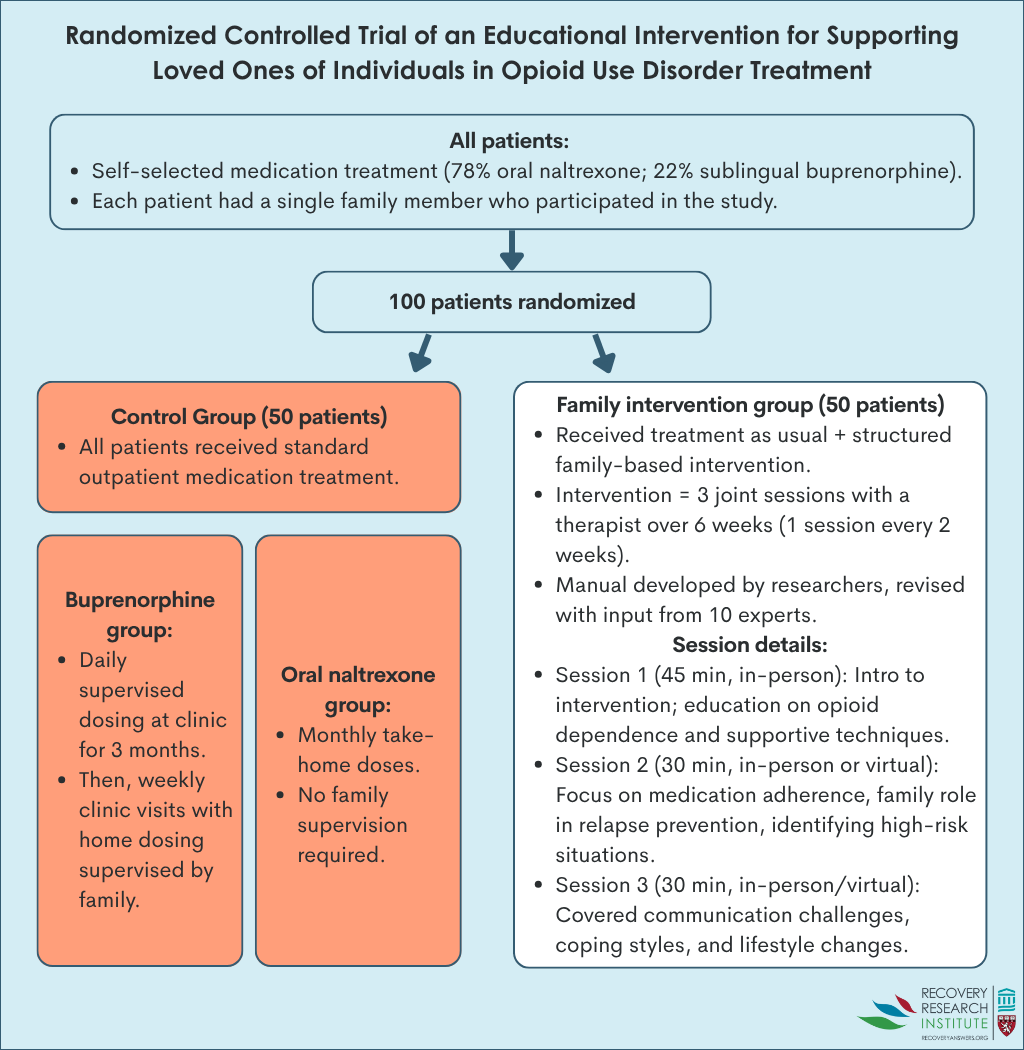

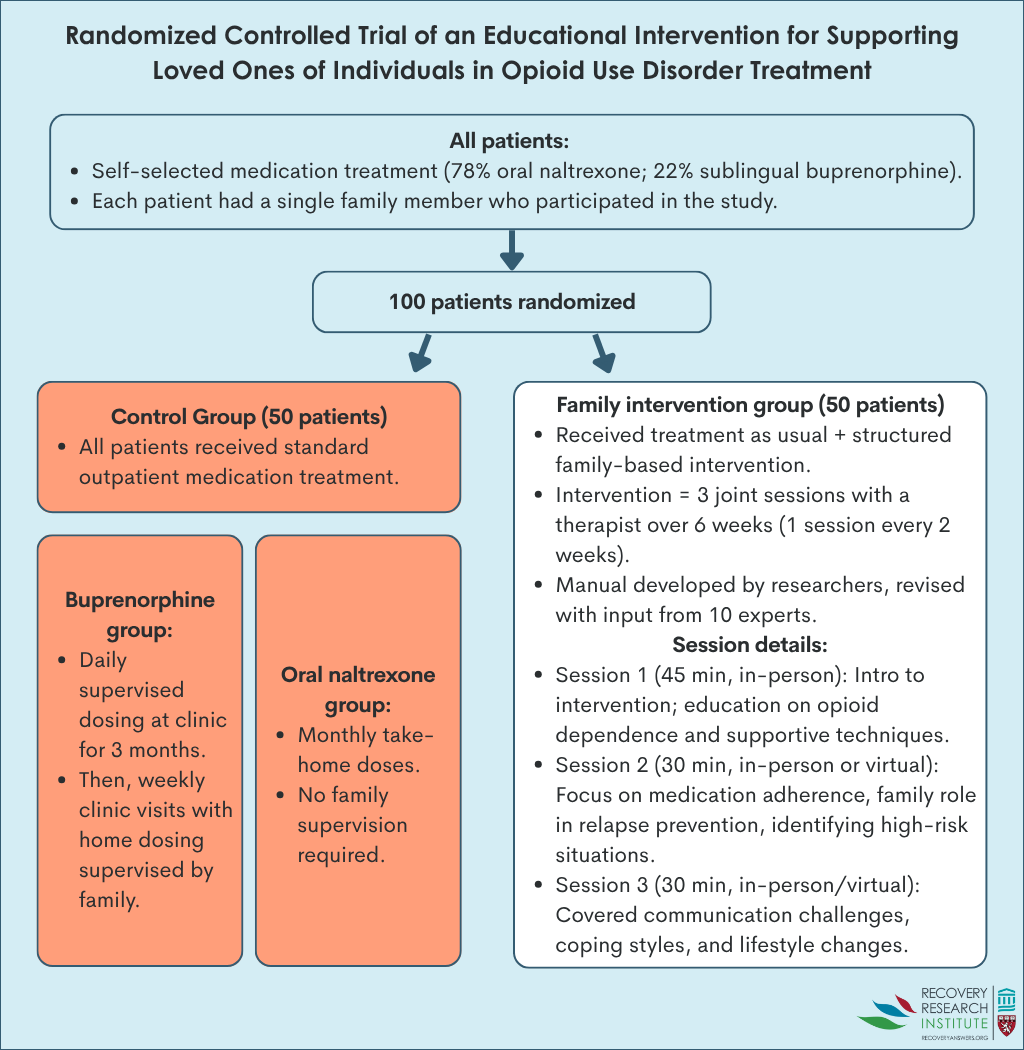

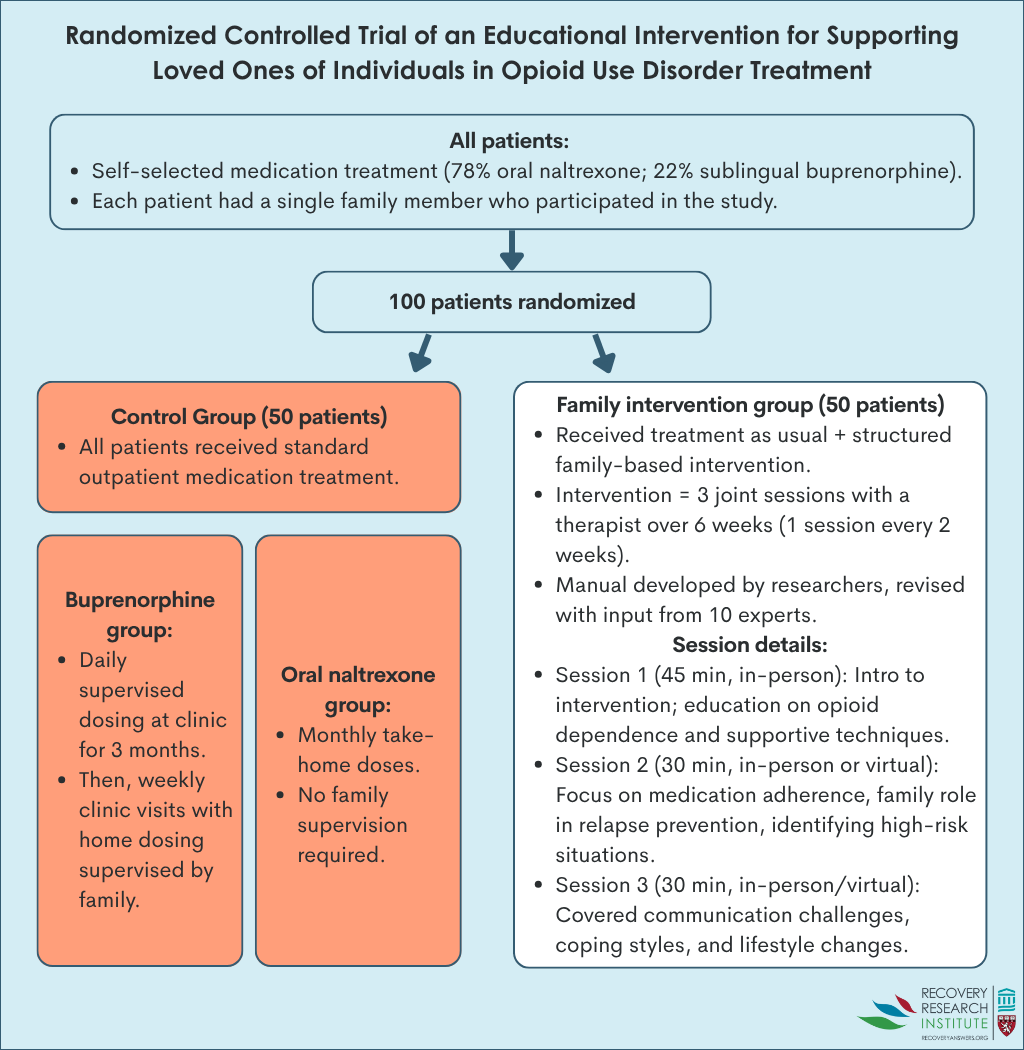

This study was a parallel, randomized controlled trial of a new intervention for families of individuals receiving medication treatment for opioid use disorder, which addressed patient and family education on the nature of opioid use disorder, relapse prevention, and the role of family in supporting treatment and relapse prevention, with the goal of improving family functioning and treatment outcomes. See the graphic below describing interventions and study procedures.

Patients with opioid use disorder were recruited from a publicly funded, addiction treatment center in India that provided subsidized medical services to people with substance use disorder, including services focused on preventing relapse and maintaining long-term recovery. Care at the center was provided by psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, social workers and other staff. At the time of study enrollment, all patients had initiated medication treatment (78% chose oral naltrexone and 22% had chosen sublingual buprenorphine) for opioid use disorder at the center within the past 3 months. Each patient had a single family member who participated in the study. Family members of patients who participated in the study were adults without current substance use disorders, who lived with the respective patients.

The researchers studied differences in family functioning, opioid use, and their change over time between participants assigned to the intervention group and the control group. Change in family functioning between the intervention and control groups was assessed with the McMaster Family Assessment Device, which provides a total measure of family functioning, as well as functioning in 7 domains, including:

1) Problem-solving: Ability of family members to effectively resolve problems

2) Communication: Quality of information exchange among family

3) Roles: Consistency of behaviors that fulfill family responsibilities

4) Affective responsiveness: Ability to express appropriate emotions in different situations

5) Affective involvement: Degree of emotional warmth and concern among family

6) Behavioral control: Existence of family social norms to guide behavioral reactions

7) General functioning: The level of general family functioning

Each subscale score ranges from 1 (healthy functioning) to 4 (unhealthy functioning), with higher scores reflecting worse family functioning. The family assessment was administered to patients and their family members at the start of the study and 12 weeks later. Opioid use among patients was measured as the mean number of days of opioid use in the past month, assessed by-self report at study start, and 4, 8, and 12 weeks later.

Intervention group differences were analyzed within family members and within patient participants, based on group assignment at baseline. Participants were included in analyses regardless of whether or not they dropped out of the study.

All patients in the study were men. The majority of patients lived in rural regions of India (80%). On average and compared to patients in the control group, the intervention patient group was slightly older (30 vs. 26 years), had a slightly higher monthly income (10,000 vs. 9,000 Indian Rupees), were much more likely to have over 10 years of education (72% vs. 50%), and substantially more likely to have injected opioids (54% vs. 28%) – a marker of opioid use disorder severity. Importantly, the intervention and control had similar numbers of patients on buprenorphine and oral naltrexone. None of the patients had received psychosocial addiction treatment prior to study enrollment. The majority of patients’ family members who participated in the study were women (62%), with over 10 years of education (56%). On average, family members were in their late 30’s to early 40’s and were primarily parents of patients (48% parent, 25% spouse, 26% sibling, 1% other). Family members participating in the intervention and control group had similar characteristics. The patient and their family member were required to agree to working together prior to study participation.

Data was missing for 47% of patients at the 12-week follow up, with almost all of these individuals (45 of the 47) dropping out by the 4-week follow up. Of those who dropped out, 36% were in the intervention group and 58% were in the control group, a significant difference. Patients lost to follow up had worse family functioning at baseline than patients who were retained, indicated by higher average scores on the McMaster Family Assessment Device (total score of 145 vs. 139). They tried to account for this high drop-out rate by including everybody in final analyses even if they dropped out – called “intent to treat”. While the study does not indicate what method they used to account for this dropout, presumably they used a method called last observation carried forward where if a 4-week assessment is missing, for example, the last observation – at baseline – would count as both their 4 and 12-week assessment scores. Also notably, the study does not indicate what proportion of intervention participants received the intervention or among those who did, how many sessions on average they attended.

The intervention overall did not improve family functioning

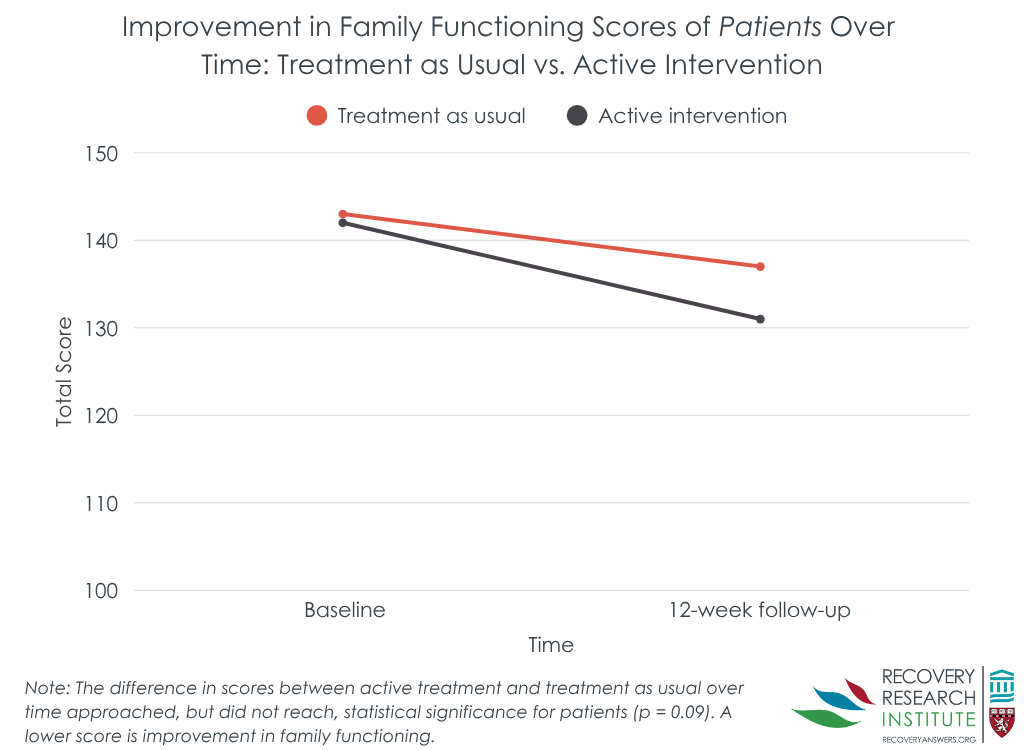

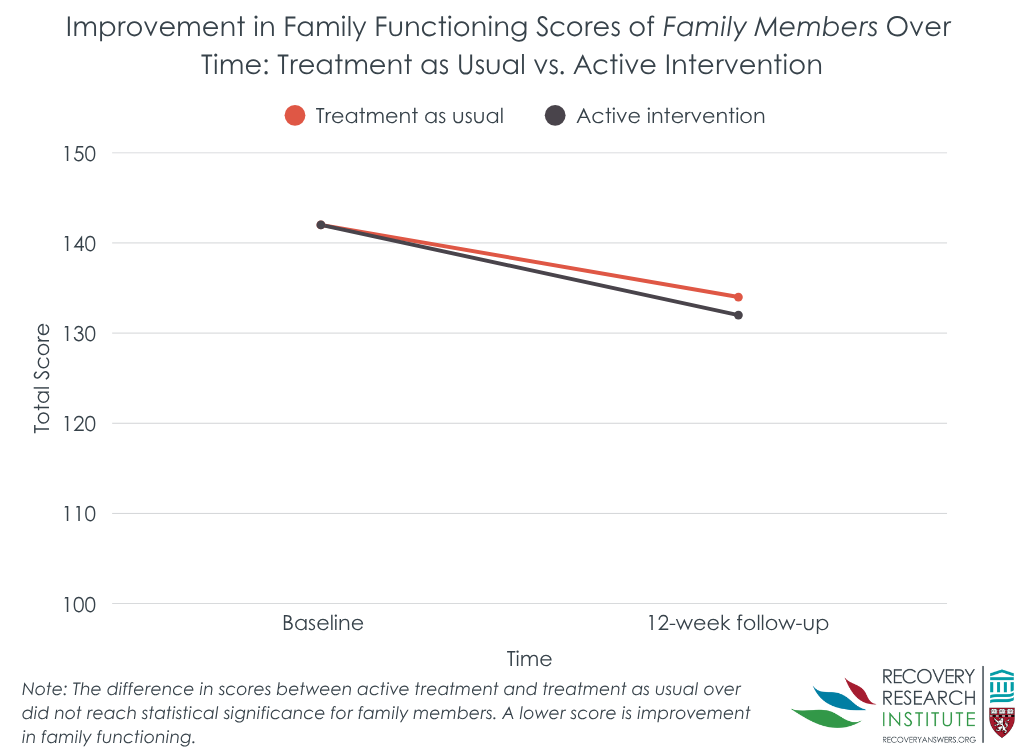

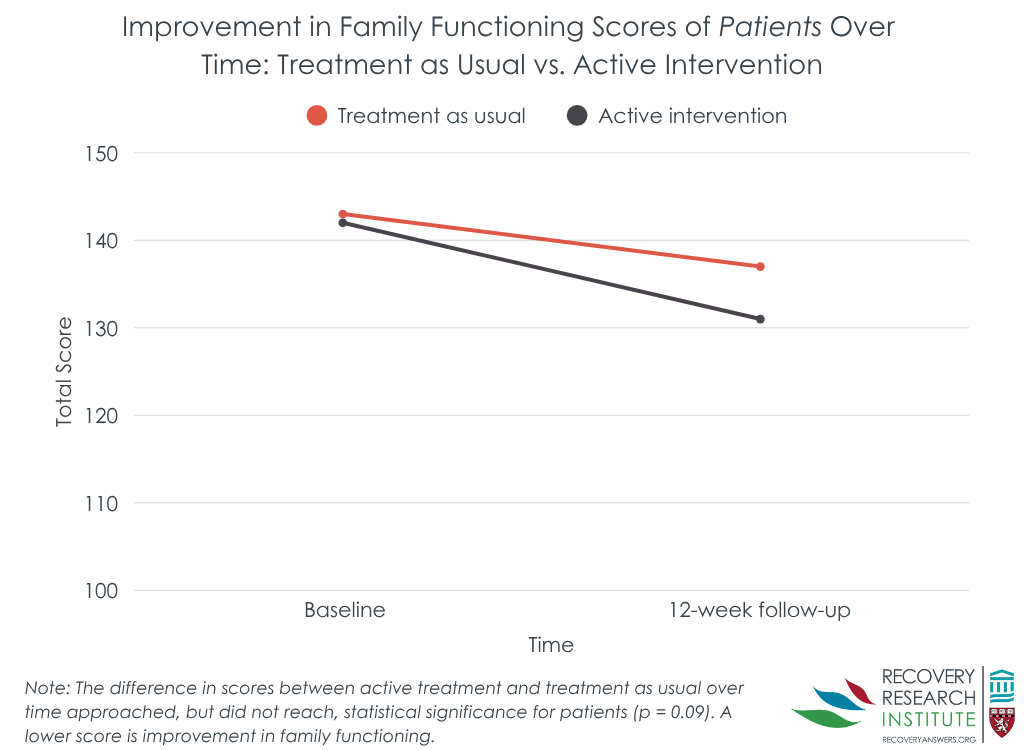

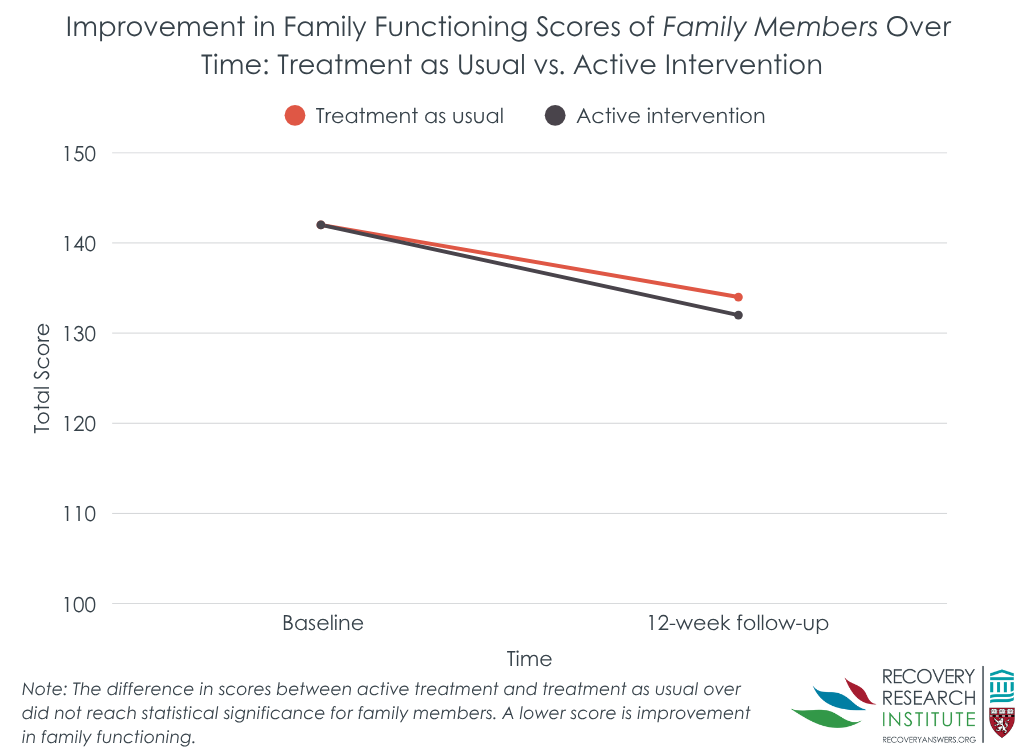

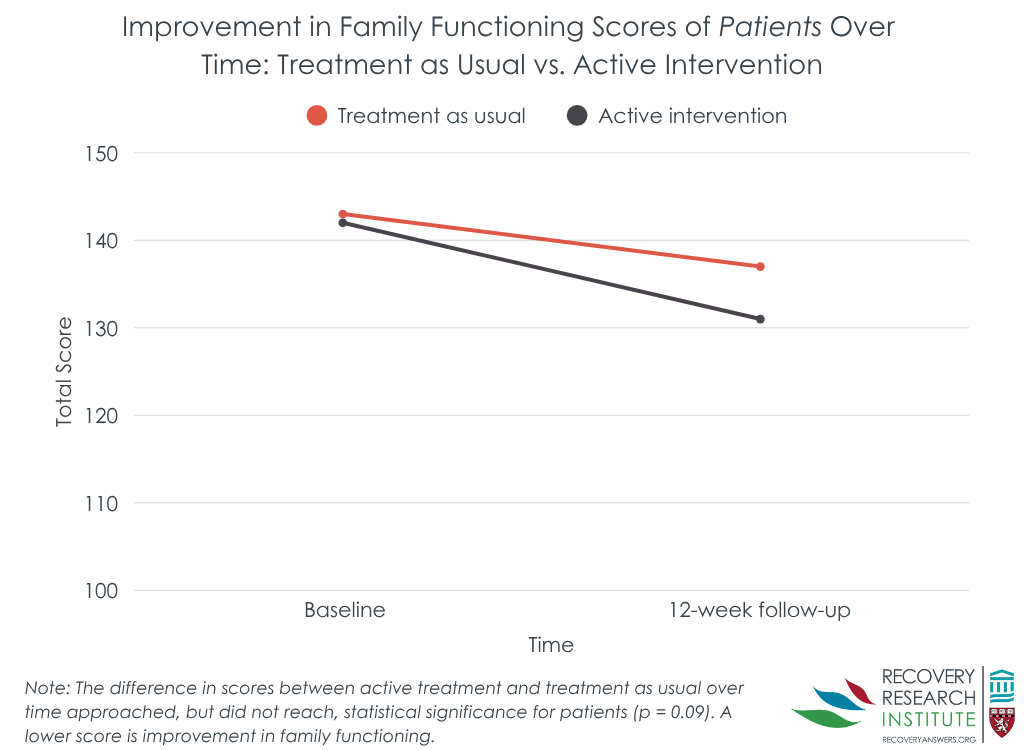

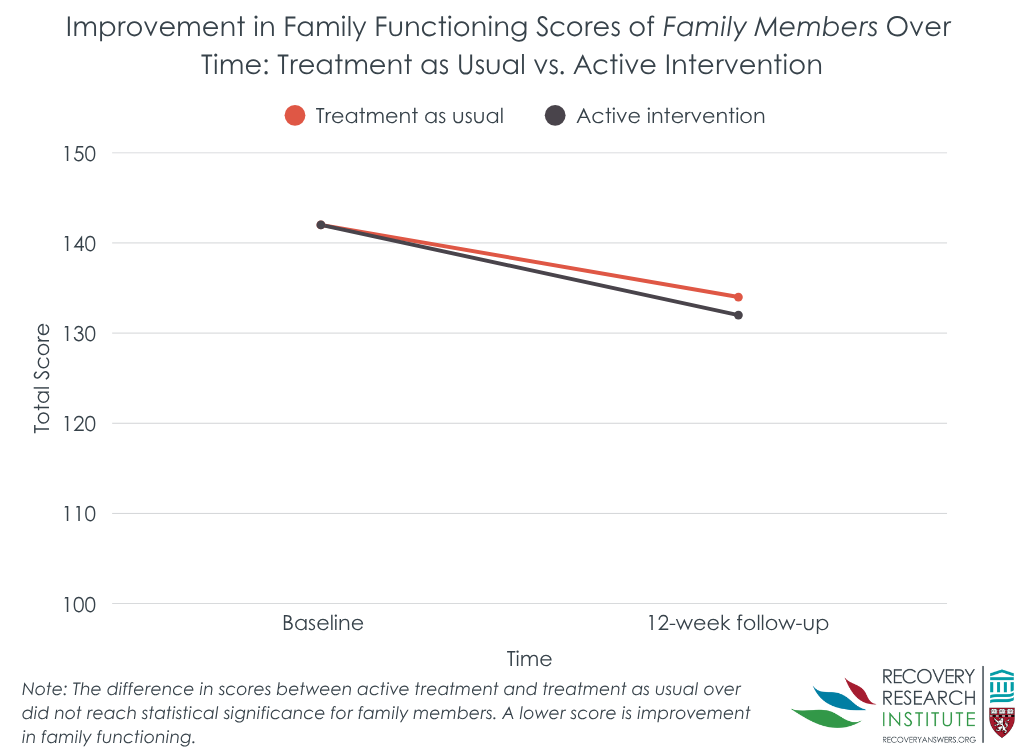

Patients who received the family intervention and treatment as usual had similar total family functioning scores on the McMaster Family Assessment Device over time. Family members of patients had similar outcomes. Both patient and family-member groups showed improvements over time. Patients in the intervention group had an 8% improvement in their total family functioning score, and the control group a 4% improvement. Family members in the intervention and control groups showed 7% and 5% improvement, respectively. In one exception to the general similar effects between intervention and control, the intervention group had greater improvements on general family functioning.

That said, the randomization to groups did not completely even out, potentially influencing variables that might predict outcomes. Notably, the family intervention group had almost twice the number of injection drug users in it compared to the control group. Injection drug use is a marker of opioid use disorder severity. Thus, the intervention group might have outperformed the comparison group were there more of an even split across groups on this variable. In addition, more control than intervention patients dropped out of the study (58 to 36%), which could mean that the family intervention helped keep patients and their family members engaged in treatment.

Opioid use was somewhat lower among patients in the intervention group at week-4 follow up

The intervention had somewhat lower past-month opioid use at the 4-week follow up (6.0 vs. 3.4 days) though this difference did not quite reach statistical significance. That difference was no longer present, however, 4 and 8 weeks later, where the intervention and control had similar opioid use days.

This study investigated a new brief intervention for individuals receiving medication treatment for opioid use disorder and their family members that can be administered in only 3 sessions. The intervention is designed to educate patients and family members about opioid use disorder and how these family supports can enhance their loved one’s treatment and recovery. Results suggest that adding a brief family-based intervention to standard outpatient medication treatment may not be enough to significantly improve family functioning in patients and their family members and ultimately improve patient’s outcome regarding opioid use. Importantly, although participants were randomized, the intervention group started the study with greater severity. With more balanced groups, the family intervention may have demonstrated a clearer benefit. Also, many more patients in the intervention compared to the control group remained in the study, suggesting the family intervention could help keep patients engaged.

That said, since more individuals dropped out of the control group, any progress in this group was not well captured – in this case, potentially making the intervention look better than it would have otherwise. Overall, the high drop-out and unequal groups at baseline have substantial implications for interpreting the impact of an intervention like the one studied here and needs additional research replication to determine the full extent to which an intervention like this can affect family functioning and recovery outcomes to support patients on their recovery journeys. Irrespective of whether the intervention was effective, those who dropped out had worse functioning when entering the study. Therefore, individuals with more complex family dynamics at the onset of treatment may require more engaging and/or intensive family-based interventions to retain them in such programs so that they might benefit.

This study suggests that adding a brief 3-session family-based intervention to standard outpatient medication treatment for opioid use disorder may not be enough to significantly improve illicit opioid use or family functioning in patients and their family members. Results from this study should be interpreted with caution, however, as ~50% of patients dropped out before the intervention was fully delivered and the intervention condition was more severe (e.g., twice the rate of lifetime injection drug use) despite randomization.

Singh, Y. C., Sarkar, S., Kaloiya, G. S., & Dhawan, A. (2025). A randomized controlled trial of effectiveness of brief structured family intervention for patients with opioid dependence and their family members. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 269. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2025.112602.

l

Many family-based psychosocial therapies have positive effects on opioid use disorder treatment outcomes. Given that medications (i.e. buprenorphine, methadone, naltrexone) are first-line treatment approaches for opioid use disorder, studies have also begun to identify new ways to incorporate family-based interventions into medication treatment programs to enhance treatment and recovery outcomes.

Such interventions have the potential to help overcome barriers to continuing medication treatment, and to promote sustained recovery. For example, promising interventions for adults have incorporated significant others to successfully engage their loved ones in treatment and medication adherence (e.g., Community Reinforcement and Family Training, or CRAFT). In addition, couples therapy aimed at building trust, compliance, and coping skills, as well as skills for crisis intervention and healthy communication between couples has shown to significantly reduce illicit drug use as well as family and social problems, relative to treatment as usual with methadone and individual counseling. Other research has demonstrated the positive effects of multi-family therapy during methadone treatment, which involves group meetings between families and patients with addiction to address communication and relationship aspects of family and substance use disorder, ultimately reducing addiction severity and improving social support more than treatment as usual. Despite the positive results of these studies, mixed outcomes are seen for a variety of interventions and patient groups. Many existing interventions are also time and resource intensive (e.g., multiple sessions, trained staff), limiting their reach to settings that already have many resources.

Additional research is needed to develop and test novel, briefer interventions that can be administered more easily in diverse treatment and recovery settings, including those with limited resources. Research in this area might ultimately identify cost-effective, low-barrier interventions that enhance treatment and promote continuing care for better recovery outcomes among individuals who are receiving medications to treat their opioid use disorder. This randomized controlled trial examined the effects of a new 3-session, family-based intervention on family functioning and patient opioid use during the early stages of opioid use disorder medication treatment, in a resource-limited medical setting in India.

This study was a parallel, randomized controlled trial of a new intervention for families of individuals receiving medication treatment for opioid use disorder, which addressed patient and family education on the nature of opioid use disorder, relapse prevention, and the role of family in supporting treatment and relapse prevention, with the goal of improving family functioning and treatment outcomes. See the graphic below describing interventions and study procedures.

Patients with opioid use disorder were recruited from a publicly funded, addiction treatment center in India that provided subsidized medical services to people with substance use disorder, including services focused on preventing relapse and maintaining long-term recovery. Care at the center was provided by psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, social workers and other staff. At the time of study enrollment, all patients had initiated medication treatment (78% chose oral naltrexone and 22% had chosen sublingual buprenorphine) for opioid use disorder at the center within the past 3 months. Each patient had a single family member who participated in the study. Family members of patients who participated in the study were adults without current substance use disorders, who lived with the respective patients.

The researchers studied differences in family functioning, opioid use, and their change over time between participants assigned to the intervention group and the control group. Change in family functioning between the intervention and control groups was assessed with the McMaster Family Assessment Device, which provides a total measure of family functioning, as well as functioning in 7 domains, including:

1) Problem-solving: Ability of family members to effectively resolve problems

2) Communication: Quality of information exchange among family

3) Roles: Consistency of behaviors that fulfill family responsibilities

4) Affective responsiveness: Ability to express appropriate emotions in different situations

5) Affective involvement: Degree of emotional warmth and concern among family

6) Behavioral control: Existence of family social norms to guide behavioral reactions

7) General functioning: The level of general family functioning

Each subscale score ranges from 1 (healthy functioning) to 4 (unhealthy functioning), with higher scores reflecting worse family functioning. The family assessment was administered to patients and their family members at the start of the study and 12 weeks later. Opioid use among patients was measured as the mean number of days of opioid use in the past month, assessed by-self report at study start, and 4, 8, and 12 weeks later.

Intervention group differences were analyzed within family members and within patient participants, based on group assignment at baseline. Participants were included in analyses regardless of whether or not they dropped out of the study.

All patients in the study were men. The majority of patients lived in rural regions of India (80%). On average and compared to patients in the control group, the intervention patient group was slightly older (30 vs. 26 years), had a slightly higher monthly income (10,000 vs. 9,000 Indian Rupees), were much more likely to have over 10 years of education (72% vs. 50%), and substantially more likely to have injected opioids (54% vs. 28%) – a marker of opioid use disorder severity. Importantly, the intervention and control had similar numbers of patients on buprenorphine and oral naltrexone. None of the patients had received psychosocial addiction treatment prior to study enrollment. The majority of patients’ family members who participated in the study were women (62%), with over 10 years of education (56%). On average, family members were in their late 30’s to early 40’s and were primarily parents of patients (48% parent, 25% spouse, 26% sibling, 1% other). Family members participating in the intervention and control group had similar characteristics. The patient and their family member were required to agree to working together prior to study participation.

Data was missing for 47% of patients at the 12-week follow up, with almost all of these individuals (45 of the 47) dropping out by the 4-week follow up. Of those who dropped out, 36% were in the intervention group and 58% were in the control group, a significant difference. Patients lost to follow up had worse family functioning at baseline than patients who were retained, indicated by higher average scores on the McMaster Family Assessment Device (total score of 145 vs. 139). They tried to account for this high drop-out rate by including everybody in final analyses even if they dropped out – called “intent to treat”. While the study does not indicate what method they used to account for this dropout, presumably they used a method called last observation carried forward where if a 4-week assessment is missing, for example, the last observation – at baseline – would count as both their 4 and 12-week assessment scores. Also notably, the study does not indicate what proportion of intervention participants received the intervention or among those who did, how many sessions on average they attended.

The intervention overall did not improve family functioning

Patients who received the family intervention and treatment as usual had similar total family functioning scores on the McMaster Family Assessment Device over time. Family members of patients had similar outcomes. Both patient and family-member groups showed improvements over time. Patients in the intervention group had an 8% improvement in their total family functioning score, and the control group a 4% improvement. Family members in the intervention and control groups showed 7% and 5% improvement, respectively. In one exception to the general similar effects between intervention and control, the intervention group had greater improvements on general family functioning.

That said, the randomization to groups did not completely even out, potentially influencing variables that might predict outcomes. Notably, the family intervention group had almost twice the number of injection drug users in it compared to the control group. Injection drug use is a marker of opioid use disorder severity. Thus, the intervention group might have outperformed the comparison group were there more of an even split across groups on this variable. In addition, more control than intervention patients dropped out of the study (58 to 36%), which could mean that the family intervention helped keep patients and their family members engaged in treatment.

Opioid use was somewhat lower among patients in the intervention group at week-4 follow up

The intervention had somewhat lower past-month opioid use at the 4-week follow up (6.0 vs. 3.4 days) though this difference did not quite reach statistical significance. That difference was no longer present, however, 4 and 8 weeks later, where the intervention and control had similar opioid use days.

This study investigated a new brief intervention for individuals receiving medication treatment for opioid use disorder and their family members that can be administered in only 3 sessions. The intervention is designed to educate patients and family members about opioid use disorder and how these family supports can enhance their loved one’s treatment and recovery. Results suggest that adding a brief family-based intervention to standard outpatient medication treatment may not be enough to significantly improve family functioning in patients and their family members and ultimately improve patient’s outcome regarding opioid use. Importantly, although participants were randomized, the intervention group started the study with greater severity. With more balanced groups, the family intervention may have demonstrated a clearer benefit. Also, many more patients in the intervention compared to the control group remained in the study, suggesting the family intervention could help keep patients engaged.

That said, since more individuals dropped out of the control group, any progress in this group was not well captured – in this case, potentially making the intervention look better than it would have otherwise. Overall, the high drop-out and unequal groups at baseline have substantial implications for interpreting the impact of an intervention like the one studied here and needs additional research replication to determine the full extent to which an intervention like this can affect family functioning and recovery outcomes to support patients on their recovery journeys. Irrespective of whether the intervention was effective, those who dropped out had worse functioning when entering the study. Therefore, individuals with more complex family dynamics at the onset of treatment may require more engaging and/or intensive family-based interventions to retain them in such programs so that they might benefit.

This study suggests that adding a brief 3-session family-based intervention to standard outpatient medication treatment for opioid use disorder may not be enough to significantly improve illicit opioid use or family functioning in patients and their family members. Results from this study should be interpreted with caution, however, as ~50% of patients dropped out before the intervention was fully delivered and the intervention condition was more severe (e.g., twice the rate of lifetime injection drug use) despite randomization.

Singh, Y. C., Sarkar, S., Kaloiya, G. S., & Dhawan, A. (2025). A randomized controlled trial of effectiveness of brief structured family intervention for patients with opioid dependence and their family members. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 269. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2025.112602.

l

Many family-based psychosocial therapies have positive effects on opioid use disorder treatment outcomes. Given that medications (i.e. buprenorphine, methadone, naltrexone) are first-line treatment approaches for opioid use disorder, studies have also begun to identify new ways to incorporate family-based interventions into medication treatment programs to enhance treatment and recovery outcomes.

Such interventions have the potential to help overcome barriers to continuing medication treatment, and to promote sustained recovery. For example, promising interventions for adults have incorporated significant others to successfully engage their loved ones in treatment and medication adherence (e.g., Community Reinforcement and Family Training, or CRAFT). In addition, couples therapy aimed at building trust, compliance, and coping skills, as well as skills for crisis intervention and healthy communication between couples has shown to significantly reduce illicit drug use as well as family and social problems, relative to treatment as usual with methadone and individual counseling. Other research has demonstrated the positive effects of multi-family therapy during methadone treatment, which involves group meetings between families and patients with addiction to address communication and relationship aspects of family and substance use disorder, ultimately reducing addiction severity and improving social support more than treatment as usual. Despite the positive results of these studies, mixed outcomes are seen for a variety of interventions and patient groups. Many existing interventions are also time and resource intensive (e.g., multiple sessions, trained staff), limiting their reach to settings that already have many resources.

Additional research is needed to develop and test novel, briefer interventions that can be administered more easily in diverse treatment and recovery settings, including those with limited resources. Research in this area might ultimately identify cost-effective, low-barrier interventions that enhance treatment and promote continuing care for better recovery outcomes among individuals who are receiving medications to treat their opioid use disorder. This randomized controlled trial examined the effects of a new 3-session, family-based intervention on family functioning and patient opioid use during the early stages of opioid use disorder medication treatment, in a resource-limited medical setting in India.

This study was a parallel, randomized controlled trial of a new intervention for families of individuals receiving medication treatment for opioid use disorder, which addressed patient and family education on the nature of opioid use disorder, relapse prevention, and the role of family in supporting treatment and relapse prevention, with the goal of improving family functioning and treatment outcomes. See the graphic below describing interventions and study procedures.

Patients with opioid use disorder were recruited from a publicly funded, addiction treatment center in India that provided subsidized medical services to people with substance use disorder, including services focused on preventing relapse and maintaining long-term recovery. Care at the center was provided by psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, social workers and other staff. At the time of study enrollment, all patients had initiated medication treatment (78% chose oral naltrexone and 22% had chosen sublingual buprenorphine) for opioid use disorder at the center within the past 3 months. Each patient had a single family member who participated in the study. Family members of patients who participated in the study were adults without current substance use disorders, who lived with the respective patients.

The researchers studied differences in family functioning, opioid use, and their change over time between participants assigned to the intervention group and the control group. Change in family functioning between the intervention and control groups was assessed with the McMaster Family Assessment Device, which provides a total measure of family functioning, as well as functioning in 7 domains, including:

1) Problem-solving: Ability of family members to effectively resolve problems

2) Communication: Quality of information exchange among family

3) Roles: Consistency of behaviors that fulfill family responsibilities

4) Affective responsiveness: Ability to express appropriate emotions in different situations

5) Affective involvement: Degree of emotional warmth and concern among family

6) Behavioral control: Existence of family social norms to guide behavioral reactions

7) General functioning: The level of general family functioning

Each subscale score ranges from 1 (healthy functioning) to 4 (unhealthy functioning), with higher scores reflecting worse family functioning. The family assessment was administered to patients and their family members at the start of the study and 12 weeks later. Opioid use among patients was measured as the mean number of days of opioid use in the past month, assessed by-self report at study start, and 4, 8, and 12 weeks later.

Intervention group differences were analyzed within family members and within patient participants, based on group assignment at baseline. Participants were included in analyses regardless of whether or not they dropped out of the study.

All patients in the study were men. The majority of patients lived in rural regions of India (80%). On average and compared to patients in the control group, the intervention patient group was slightly older (30 vs. 26 years), had a slightly higher monthly income (10,000 vs. 9,000 Indian Rupees), were much more likely to have over 10 years of education (72% vs. 50%), and substantially more likely to have injected opioids (54% vs. 28%) – a marker of opioid use disorder severity. Importantly, the intervention and control had similar numbers of patients on buprenorphine and oral naltrexone. None of the patients had received psychosocial addiction treatment prior to study enrollment. The majority of patients’ family members who participated in the study were women (62%), with over 10 years of education (56%). On average, family members were in their late 30’s to early 40’s and were primarily parents of patients (48% parent, 25% spouse, 26% sibling, 1% other). Family members participating in the intervention and control group had similar characteristics. The patient and their family member were required to agree to working together prior to study participation.

Data was missing for 47% of patients at the 12-week follow up, with almost all of these individuals (45 of the 47) dropping out by the 4-week follow up. Of those who dropped out, 36% were in the intervention group and 58% were in the control group, a significant difference. Patients lost to follow up had worse family functioning at baseline than patients who were retained, indicated by higher average scores on the McMaster Family Assessment Device (total score of 145 vs. 139). They tried to account for this high drop-out rate by including everybody in final analyses even if they dropped out – called “intent to treat”. While the study does not indicate what method they used to account for this dropout, presumably they used a method called last observation carried forward where if a 4-week assessment is missing, for example, the last observation – at baseline – would count as both their 4 and 12-week assessment scores. Also notably, the study does not indicate what proportion of intervention participants received the intervention or among those who did, how many sessions on average they attended.

The intervention overall did not improve family functioning

Patients who received the family intervention and treatment as usual had similar total family functioning scores on the McMaster Family Assessment Device over time. Family members of patients had similar outcomes. Both patient and family-member groups showed improvements over time. Patients in the intervention group had an 8% improvement in their total family functioning score, and the control group a 4% improvement. Family members in the intervention and control groups showed 7% and 5% improvement, respectively. In one exception to the general similar effects between intervention and control, the intervention group had greater improvements on general family functioning.

That said, the randomization to groups did not completely even out, potentially influencing variables that might predict outcomes. Notably, the family intervention group had almost twice the number of injection drug users in it compared to the control group. Injection drug use is a marker of opioid use disorder severity. Thus, the intervention group might have outperformed the comparison group were there more of an even split across groups on this variable. In addition, more control than intervention patients dropped out of the study (58 to 36%), which could mean that the family intervention helped keep patients and their family members engaged in treatment.

Opioid use was somewhat lower among patients in the intervention group at week-4 follow up

The intervention had somewhat lower past-month opioid use at the 4-week follow up (6.0 vs. 3.4 days) though this difference did not quite reach statistical significance. That difference was no longer present, however, 4 and 8 weeks later, where the intervention and control had similar opioid use days.

This study investigated a new brief intervention for individuals receiving medication treatment for opioid use disorder and their family members that can be administered in only 3 sessions. The intervention is designed to educate patients and family members about opioid use disorder and how these family supports can enhance their loved one’s treatment and recovery. Results suggest that adding a brief family-based intervention to standard outpatient medication treatment may not be enough to significantly improve family functioning in patients and their family members and ultimately improve patient’s outcome regarding opioid use. Importantly, although participants were randomized, the intervention group started the study with greater severity. With more balanced groups, the family intervention may have demonstrated a clearer benefit. Also, many more patients in the intervention compared to the control group remained in the study, suggesting the family intervention could help keep patients engaged.

That said, since more individuals dropped out of the control group, any progress in this group was not well captured – in this case, potentially making the intervention look better than it would have otherwise. Overall, the high drop-out and unequal groups at baseline have substantial implications for interpreting the impact of an intervention like the one studied here and needs additional research replication to determine the full extent to which an intervention like this can affect family functioning and recovery outcomes to support patients on their recovery journeys. Irrespective of whether the intervention was effective, those who dropped out had worse functioning when entering the study. Therefore, individuals with more complex family dynamics at the onset of treatment may require more engaging and/or intensive family-based interventions to retain them in such programs so that they might benefit.

This study suggests that adding a brief 3-session family-based intervention to standard outpatient medication treatment for opioid use disorder may not be enough to significantly improve illicit opioid use or family functioning in patients and their family members. Results from this study should be interpreted with caution, however, as ~50% of patients dropped out before the intervention was fully delivered and the intervention condition was more severe (e.g., twice the rate of lifetime injection drug use) despite randomization.

Singh, Y. C., Sarkar, S., Kaloiya, G. S., & Dhawan, A. (2025). A randomized controlled trial of effectiveness of brief structured family intervention for patients with opioid dependence and their family members. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 269. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2025.112602.

151 Merrimac St., 4th Floor. Boston, MA 02114